Validating Pharmacometric Models for Dose Prediction: A Framework for Accuracy, Credibility, and Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of pharmacometric models for accurate dose prediction.

Validating Pharmacometric Models for Dose Prediction: A Framework for Accuracy, Credibility, and Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of pharmacometric models for accurate dose prediction. It explores the foundational principles of pharmacometrics and its critical role in model-informed drug development (MIDD). The content delves into advanced methodological approaches, including the integration of real-world data and pharmacogenomics, and addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges faced during model development. A significant focus is placed on contemporary validation frameworks and comparative analyses with traditional statistical methods, highlighting tools like the risk-informed credibility framework and novel visualization techniques. By synthesizing current trends, regulatory expectations, and real-world applications, this article serves as a strategic resource for enhancing the reliability and clinical impact of pharmacometric models in personalized medicine.

The Foundations of Pharmacometrics and Its Pivotal Role in Modern Dose Prediction

Pharmacometrics represents the scientific discipline concerned with the quantitative analysis of the interactions between drugs and biological systems. As a cornerstone of Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD), pharmacometrics employs mathematical models to characterize, understand, and predict pharmacokinetic (PK), pharmacodynamic (PD), and disease progression behaviors [1] [2]. This quantitative framework integrates data from nonclinical and clinical studies to inform critical decisions throughout the drug development lifecycle, from early discovery to post-market optimization [3].

The fundamental importance of pharmacometrics lies in its ability to quantify uncertainty and variability in drug response, enabling more efficient drug development and regulatory decision-making [3] [4]. By bridging diverse data types through modeling and simulation, pharmacometrics provides a structured approach to address key questions of interest (QOI) within specific contexts of use (COU), ultimately supporting dose selection, trial design, and optimization of therapeutic individualization [1]. The recent International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) M15 guidelines on MIDD further underscore the regulatory recognition of pharmacometrics as an essential tool for modern drug development, establishing harmonized expectations for model development, documentation, and application across global regulatory agencies [3] [4].

Core Components of the Pharmacometric Toolkit

Pharmacokinetic (PK) Modeling: The Journey of Drugs Through the Body

Pharmacokinetic modeling quantitatively describes the time course of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) within the body [3]. PK models range from simple compartmental structures to sophisticated physiologically-based frameworks, each serving distinct purposes throughout drug development.

Population PK (PopPK) modeling represents a preeminent methodology that characterizes drug concentration time profiles while accounting for inter-individual variability [1] [3]. Using nonlinear mixed-effects modeling, PopPK identifies demographic, physiological, and pathological factors that contribute to variability in drug exposure, enabling tailored dosing strategies for specific patient subpopulations [3]. For instance, a PopPK model for sitafloxacin incorporated covariates including creatinine clearance, body weight, age, and food effects to optimize dosing regimens against various bacterial pathogens [5].

Physiologically-Based PK (PBPK) modeling adopts a mechanistic approach that incorporates physiological, biochemical, and drug-specific parameters to simulate drug disposition [1]. These models are particularly valuable for predicting drug-drug interactions, extrapolating across populations, and supporting biopharmaceutics applications. Recent data indicates that approximately 70% of PBPK applications in regulatory submissions focus on predicting enzyme- and transporter-mediated drug interactions [3].

Pharmacodynamic (PD) Modeling: Quantifying Drug Effects

Pharmacodynamic modeling characterizes the relationship between drug concentration at the site of action and the resulting pharmacological effects, both desired and adverse [3]. PD models quantify the intensity and time course of drug responses, incorporating specific mechanisms of action when knowledge is available.

Exposure-Response (E-R) analysis represents a fundamental PD approach that establishes relationships between drug exposure metrics (e.g., AUC, Cmax) and efficacy or safety endpoints [1] [3]. These relationships are crucial for determining therapeutic windows and informing dosing recommendations. For example, E-R analysis for nedosiran established the relationship between plasma concentrations and reduction in urine oxalate-to-creatinine ratio, supporting dose justification for pediatric patients with primary hyperoxaluria type 1 [6].

Semi-mechanistic PK/PD modeling hybridizes empirical and mechanism-based elements to characterize the complex interplay between drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic responses [1]. These models often incorporate biomarkers and intermediate endpoints to bridge between drug exposure and clinical outcomes, particularly valuable when clinical endpoints are delayed or difficult to measure frequently.

Disease Progression Modeling: Quantifying the Natural History

Disease progression modeling mathematically describes the time course or trajectory of a disease under natural conditions or standard of care [7]. These models distinguish drug effects from underlying disease evolution, providing critical context for interpreting treatment outcomes.

Disease progression models integrate multi-disciplinary knowledge and data from different sources, including translational, clinical trial, and real-world data [7]. They offer particular value for chronic conditions with slow progression, such as neurodegenerative diseases, where long-term clinical trials would be impractical and costly. By accounting for heterogeneity across patients and disease stages, these models support precision medicine approaches through population stratification and tailored treatment plans [7].

The synergy between these modeling components creates a comprehensive framework for understanding the complete drug-disease-patient system, enabling more informed decision-making throughout drug development.

Comparative Analysis: PK, PD, and Disease Progression Modeling

Table 1: Comparison of Core Pharmacometric Modeling Approaches

| Model Type | Primary Focus | Key Applications | Common Methodologies | Regulatory Impact Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacokinetic (PK) | Drug concentration time course | Dose selection, Bioequivalence, Drug interactions | Compartmental modeling, PBPK, PopPK | First-in-human dose prediction, DDI assessment [1] [3] |

| Pharmacodynamic (PD) | Drug effect intensity and time course | Target engagement, Efficacy/safety relationships | Emax models, Indirect response, Transit models | Exposure-response justification, Therapeutic window determination [1] [3] |

| Disease Progression | Natural history of disease | Trial optimization, Endpoint selection, Digital twins | Linear/Non-linear progression, Markov models | Patient enrichment strategies, External control arms [7] |

Integrated Modeling: The Synergy of PK, PD, and Disease Progression

The true power of pharmacometrics emerges when PK, PD, and disease progression models are integrated to form comprehensive drug-disease models. These integrated frameworks simultaneously characterize the complex interplay between drug exposure, pharmacological effects, and disease trajectory, providing a more holistic understanding of the overall system [2].

A compelling example of this integration is demonstrated in the development of teclistamab, a T-cell redirecting bispecific antibody for multiple myeloma [2]. The model-informed strategy incorporated translational PK/PD modeling from discovery through clinical development, integrating target receptor occupancy predictions with cytokine release syndrome assessment using PBPK approaches. This integrated modeling supported optimized dosing regimens and informed risk mitigation strategies, ultimately contributing to the successful regulatory approval of teclistamab [2].

Another exemplar of integrated modeling comes from the development of nedosiran for primary hyperoxaluria type 1 [6]. A population PK/PD model characterized the relationship between nedosiran exposure and reduction in spot urine oxalate-to-creatinine ratio across pediatric and adult populations. This model incorporated covariates such as body weight, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and PH type, enabling extrapolation of efficacy from adults to children as young as 2 years old and supporting the approved dosing regimen [6].

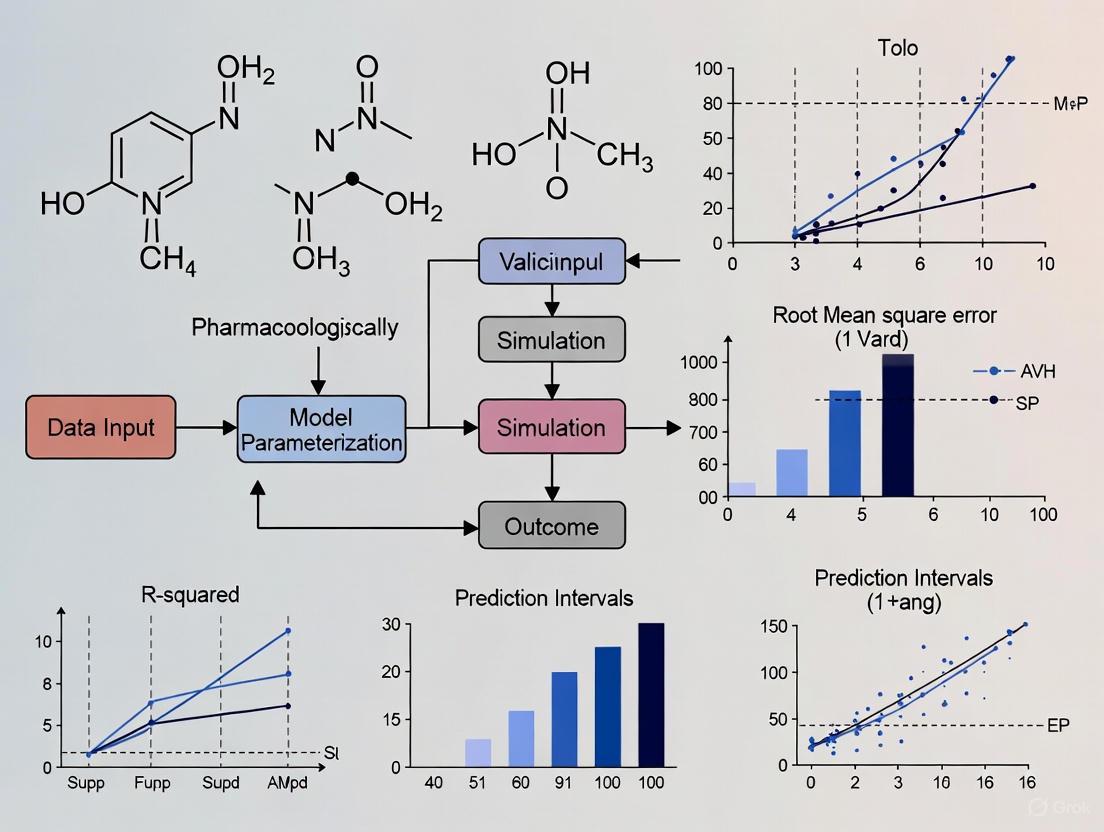

Diagram 1: Integrated Pharmacometric Modeling Framework. This diagram illustrates the synergistic relationships between PK, PD, and disease progression models in predicting clinical outcomes.

Validation Frameworks and Regulatory Considerations

Model Credibility and Validation Standards

The regulatory acceptance of pharmacometric models depends heavily on establishing model credibility through rigorous verification and validation processes [3] [4]. The ICH M15 guidelines adopt a risk-based approach to model assessment, considering the decision consequences and model influence on regulatory outcomes [3]. The validation framework encompasses several critical components:

Verification ensures that the computational model correctly implements the intended mathematical representations and algorithms [3] [4]. This process confirms that the model is solved accurately without coding or implementation errors.

Validation assesses how well the model represents reality for its intended context of use [3] [4]. This includes evaluating the model's predictive performance against external data sets not used in model development.

Applicability establishes that the model is appropriate for addressing the specific question of interest within the defined context of use [3]. This involves evaluating whether model assumptions, structure, and data sources are suitable for the intended application.

A recent validation study demonstrated this framework by evaluating mathematical model-based pharmacogenomic dose predictions against real-world data [8]. The study collected dosing and genotype information from 1,914 subjects across 26 studies, focusing on CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 polymorphisms. Results confirmed that the mathematical model could accurately predict optimal dosing, potentially circumventing traditional trial-and-error approaches to dose individualization [8].

Regulatory Evolution and Current Landscape

The regulatory landscape for pharmacometrics has evolved significantly over the past decades, with growing acceptance of model-informed approaches across global health authorities [3] [2]. This evolution began with the FDA's Population PK guidance in 1999 and Exposure-Response guidance in 2003, culminating in the recent ICH M15 draft guideline on "General Principles for Model-Informed Drug Development" [3].

The ICH M15 guideline aims to harmonize expectations between regulators and sponsors, supporting consistent regulatory decisions and minimizing errors in the acceptance of modeling and simulation evidence [3] [4]. This harmonization is particularly valuable for global drug development programs, promoting efficient application of MIDD across different regions and regulatory agencies.

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Pharmacometric Model Validation

| Validation Component | Experimental/Methodological Approach | Acceptance Criteria | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Verification | Software qualification, Code review, Unit testing | Successful replication of benchmark results | Verification of PBPK model implementation [3] |

| Internal Validation | Bootstrap, Visual predictive checks, Data splitting | Parameter stability, Adequate uncertainty estimation | Bootstrap of sitafloxacin PopPK model (n=1000) [5] |

| External Validation | Prediction on independent datasets, Posterior predictive checks | Adequate predictive performance | CYP2D6 dose prediction vs. real-world data (n=1914) [8] |

| Sensitivity Analysis | Local/global sensitivity methods, Monte Carlo filtering | Robustness to parameter uncertainty | Covariate effect sensitivity in nedosiran model [6] |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Pharmacometrics

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) approaches represents a transformative frontier in pharmacometrics [1] [9]. Recent data indicates a substantial increase in regulatory submissions incorporating AI/ML elements, growing from fewer than 3 annually before 2019 to more than 100 each year after 2020 [2].

Machine learning techniques are being applied to enhance various aspects of pharmacometric analysis, including drug discovery optimization, ADME property prediction, and dosing strategy individualization [1]. A notable application involves automated population PK model development, where machine learning algorithms can efficiently search through thousands of potential model structures to identify optimal configurations [9]. Recent research demonstrates that such automated approaches can reliably identify model structures comparable to manually developed expert models while evaluating fewer than 2.6% of the models in the search space and reducing development time from weeks to less than 48 hours on average [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Pharmacometrics

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function/Application | Representative Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modeling Software | NONMEM, Monolix, Phoenix NLME | Nonlinear mixed-effects modeling | PopPK/PD model development [5] [9] |

| Simulation Platforms | R, Python, MATLAB | Clinical trial simulation, Data analysis | Monte Carlo simulations for PTA [5] |

| PBPK Platforms | GastroPlus, Simcyp Simulator | Mechanistic absorption and disposition prediction | DDI risk assessment [3] |

| AI/ML Tools | pyDarwin, TensorFlow, Scikit-learn | Automated model development, Pattern recognition | Automated PopPK model selection [9] |

| Data Resources | Clinical trial data, Real-world evidence, Literature | Model development and validation | Model-based meta-analysis [1] [7] |

Diagram 2: Automated Model Development Workflow. This diagram illustrates the machine learning-assisted workflow for automated population PK model development, demonstrating the iterative refinement process.

Pharmacometrics has evolved from a specialized analytical discipline to an essential framework informing decision-making across the entire drug development lifecycle. By bridging PK, PD, and disease progression modeling within integrated quantitative frameworks, pharmacometrics provides powerful tools for optimizing drug development efficiency and success rates [1] [2].

The continued adoption of model-informed drug development approaches, supported by regulatory harmonization through initiatives like ICH M15, promises to further strengthen the role of pharmacometrics in addressing complex development challenges [3] [4]. Emerging technologies, particularly artificial intelligence and machine learning, offer exciting opportunities to enhance model development efficiency and expand applications toward more personalized therapeutic interventions [1] [9].

As the field advances, the integration of diverse data sources—from advanced biomolecular assays to real-world evidence—will enable increasingly sophisticated models that better reflect the complexity of drug-disease-patient interactions. This progression toward more predictive, validated pharmacometric models will ultimately accelerate the delivery of safe and effective therapies to patients in need.

Historical Foundation and Conceptual Framework

The 'Learn and Confirm' paradigm, introduced by Lewis Sheiner in the 1990s, represents a foundational shift in pharmaceutical development [10]. It proposes a structured framework where drug development alternates between learning phases (where models are developed and refined using emerging data) and confirming phases (where model-based predictions are tested and validated in subsequent studies) [11] [10]. This iterative process stands in contrast to traditional, purely empirical development approaches.

This paradigm is the direct intellectual predecessor of modern Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD), which the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) defines as "the strategic use of computational modeling and simulation (M&S) methods that integrate nonclinical and clinical data, prior information, and knowledge to generate evidence" [3]. MIDD operationalizes 'Learn and Confirm' through quantitative pharmacology, using models to infer, predict, and inform decisions rather than to solely base decisions on them [11]. The core concept is that research and development decisions are "informed" rather than exclusively "based" on model-derived outputs, making it a central tenet of efficient drug development [11].

Table: Core Components of the Learn and Confirm Paradigm in Modern MIDD

| Component | Objective in 'Learn' Phase | Objective in 'Confirm' Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Data Utilization | Integrate existing knowledge & new data to build/refine models | Collect new, targeted data to test model predictions |

| Model Role | Characterize emerging data & underlying systems | Serve as a pre-specified framework for trial simulation & analysis |

| Primary Output | Quantitative framework for prediction & extrapolation | Substantial evidence of effectiveness & safety |

| Decision Impact | Generate hypotheses & inform design of subsequent studies | Verify model predictions & support regulatory labeling |

Contemporary Evidence of Paradigm Validation

The validation of the 'Learn and Confirm' paradigm is demonstrated through its successful application and measurable impact across the modern drug development portfolio. The following table summarizes key quantitative evidence from recent implementations.

Table: Quantitative Evidence of MIDD Impact from Recent Applications

| Application Area | Reported Impact | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Portfolio Efficiency | Average savings of ~10 months in cycle time and $5 million per program | Systematic application across a large pharmaceutical company's portfolio [12] |

| Pharmacogenomic Dose Prediction | Mathematical model accurately predicted optimal dosing for 1914 subjects across 26 studies | Validation using real-world data on CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 polymorphisms [8] [13] |

| Clinical Trial Budget | Reduction of $100 million in annual clinical trial budget | Historical implementation at Pfizer through model-informed study designs [11] [12] |

| Decision-Making Impact | Significant cost savings ($0.5 billion) through impact on decision-making | Reported impact at Merck & Co./MSD [11] |

Case Study: Validating Pharmacogenomic Dose Prediction

A 2025 study provides a robust, real-world validation of the paradigm by testing a mathematical model's ability to predict individualized drug doses based on patient genetics [8] [13].

- Experimental Protocol: The work relied on collecting, extracting, and using real-world data on dosing and patient genotypes, focusing on drug-metabolizing enzymes cytochrome CYP450, specifically CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 gene polymorphisms [8]. A total of 1914 subjects from 26 studies were considered for the verification [8].

- Key Methodology: The study emphasized using allele activity scores and simple descriptive metabolic activity terms for patients, rather than traditional phenotype/genotype classifications, to improve prediction accuracy [8].

- Outcome and Validation: The mathematical model successfully predicted the reported optimal dosing values from the considered studies [8] [13]. This demonstrates the 'Confirm' phase in action, where a model-based approach ('Learn') was validated against independent, real-world data, proving its utility in circumventing trial-and-error in patient treatment [8].

Case Study: Portfolio-Wide Efficiency Gains

A 2025 analysis systematically estimated the cumulative impact of MIDD across a clinical development portfolio, showcasing the paradigm's large-scale business value [12].

- Experimental Protocol: The methodology involved reviewing MIDD plans for all active clinical development programs (11 early-development and 31 late-development programs). An algorithm was used to estimate savings from MIDD-related activities such as clinical trial waivers, "No-Go" decisions, or sample size reductions [12].

- Key Methodology: Cost savings were calculated using Per Subject Approximation (PSA) values. Time savings were estimated using typical timelines from protocol development to the final clinical study report for waived studies [12].

- Outcome and Validation: The analysis confirmed that systematic MIDD application yielded significant annualized savings—approximately 10 months of cycle time and $5 million per program—demonstrating that the iterative 'Learn and Confirm' process directly translates into enhanced development efficiency and cost-effectiveness [12].

Regulatory Endorsement and Standardization

The principles of 'Learn and Confirm' and MIDD have evolved from a theoretical concept to a formally recognized regulatory framework. This is most evident in the development of the ICH M15 guideline on "General Principles for Model-Informed Drug Development" [3]. This guideline, released as a draft in 2024, aims to harmonize expectations between regulators and sponsors, support consistent regulatory decisions, and minimize errors in the acceptance of modeling and simulation to inform drug labels [3]. It operationalizes the paradigm by providing a taxonomy of terms and outlining stages for MIDD activities: Planning and Regulatory Interaction, Implementation, Evaluation, and Submission [3].

Furthermore, regulatory bodies have incorporated credibility assessment frameworks for computational models, directly supporting the 'Confirm' aspect of the paradigm. These frameworks, such as those adapted from the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) standards, provide a structured approach to evaluate model relevance and adequacy, ensuring the models are 'fit-for-purpose' [3] [14]. This ensures that the models used in the 'Learn' phase are robust and reliable enough to inform decisions that will be 'Confirmed' in later stages.

Essential Research Toolkit for MIDD

The successful implementation of the 'Learn and Confirm' paradigm relies on a suite of quantitative tools. The following table details key "Research Reagent Solutions" – the essential methodologies and materials in the pharmacometrician's toolkit.

Table: Essential Research Toolkit for Model-Informed Drug Development

| Tool / Methodology | Primary Function | Key Application in 'Learn and Confirm' |

|---|---|---|

| Population PK (PopPK) | Analyzes variability in drug concentrations between individuals in a patient population [15]. | 'Learn': Identifies impact of covariates (e.g., weight, genetics). 'Confirm': Validates covariate relationships in new populations [3]. |

| Physiologically-Based PK (PBPK) | Mechanistically simulates drug movement through body organs and tissues [15]. | 'Learn': Predicts human PK and drug-drug interactions. 'Confirm': Waives dedicated clinical DDI studies [15] [14]. |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) | Models drug effects in the context of biological systems and disease pathways [15]. | 'Learn': Identifies drug targets and combination therapies. 'Confirm': Optimizes dose selection and patient stratification [16] [14]. |

| Model-Based Meta-Analysis (MBMA) | Integrates highly curated summary-level data from multiple clinical trials [15]. | 'Learn': Informs competitive landscape and trial design. 'Confirm': Provides external control arms [15]. |

| AI/Machine Learning (ML) | Identifies complex patterns in large, high-dimensional datasets [16] [14]. | 'Learn': Predicts target engagement and patient endpoints. 'Confirm': Enhances model diagnostics and validation [16]. |

| Real-World Data (RWD) | Provides evidence from routine healthcare delivery (e.g., EHRs, registries) [8]. | 'Learn': Informs disease progression models. 'Confirm': Validates model-based dose predictions [8]. |

Experimental Workflow for Model Validation

The credibility of any model used in the 'Learn and Confirm' cycle is paramount. The following workflow, aligned with regulatory expectations, outlines the key steps for developing and validating a pharmacometric model for dose prediction.

- Step 1: Define Question of Interest (QOI) & Context of Use (COU): The process begins by precisely defining the specific drug development question to be answered (the QOI) and the specific context in which the model output will be used to inform a decision (the COU) [3]. This is a critical first step for 'fit-for-purpose' model development.

- Step 2: Create Model Analysis Plan (MAP): A pre-specified MAP documents the objectives, data sources, and analytical methods, minimizing bias and aligning the team and regulators on the approach [3].

- Step 3: Data Curation & Variable Selection: This involves gathering and processing high-quality, relevant data from nonclinical and clinical studies, which forms the foundation for model building [16] [3].

- Step 4: Model Development & Estimation: Using appropriate software, a mathematical model is developed, and its parameters are estimated. This may involve complex techniques like nonlinear mixed-effects modeling [3].

- Step 5: Model Evaluation: The model undergoes rigorous diagnostic checks (e.g., goodness-of-fit plots), and uncertainty in its parameters and predictions is quantified [16] [3].

- Step 6: Model Validation: The model's predictive performance is assessed. This can include internal validation (e.g., Visual Predictive Check - VPC) and external validation using a separate dataset or real-world data (RWD), as demonstrated in the pharmacogenomics case study [8] [3].

- Step 7: Submission & Regulatory Review: The final model, analysis, and documentation are submitted to regulatory agencies as part of the evidence package to support the proposed dosing regimen or other labeling claims [12] [3].

The transition of pharmacometric models from research tools to clinical decision-support systems hinges on a single, non-negotiable requirement: rigorous validation. Model validation provides the essential evidence that mathematical predictions of drug dosing can be trusted in real-world clinical settings, directly impacting patient safety and therapeutic efficacy. Within precision medicine, pharmacogenomics-based dose prediction models aim to optimize drug therapy by integrating individual genetic variability, particularly in drug-metabolizing enzymes such as cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoforms. Without thorough validation, these models remain theoretical constructs with unproven clinical utility. This guide objectively compares validation approaches and performance of different model-based dosing strategies, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the experimental data and protocols needed to critically assess model credibility for clinical implementation.

Comparative Performance of Dose Prediction Models

Quantitative Validation Metrics Across Model Types

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Pharmacogenomic Dose Prediction Models

| Model Type | Validation Cohort Size | Key Genetic Factors | Primary Validation Metric | Reported Performance | Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Model (PGx) [8] | 1,914 subjects (26 studies) | CYP2D6, CYP2C19 allele activity scores | Prediction accuracy of optimal dosing versus real-world data | Able to predict reported optimal dosing; circumvents trial-and-error [8] | Individualized dosing for drugs metabolized by CYP450 enzymes |

| Multi-output Gaussian Process (MOGP) [17] | 442 cancer cell lines (10 cancer types) | Genomic features (mutations, CNA, methylation) + drug chemistry | Prediction accuracy of full dose-response curves | Accurate prediction across cancer types; identifies novel biomarkers (e.g., EZH2) [17] | Drug repositioning and biomarker discovery in oncology |

| Software Tool for Codeine Dosing [8] | N/A (Algorithm-based) | CYP2D6 gene-pair polymorphisms + drug-drug interactions | Dose adjustment accuracy | Provides framework for implementing individualized dosing [8] | Codeine dose adjustment based on CYP2D6 phenotype |

| Precision Dosing for Tricyclics [8] | N/A (Algorithm-based) | CYP2D6, CYP2C19 variants + polypharmacy | Dosing accuracy integrating polypharmacy | More accurate individualized dosing integrating polypharmacy effect [8] | Tricyclic antidepressant dosing |

Key Validation Outcomes and Clinical Implications

The validation of mathematical model-based pharmacogenomics dosing against real-world data represents a significant advancement. A 2025 study demonstrated that a mathematical model successfully predicted the reported optimal dosing values from 26 real-world studies encompassing 1,914 subjects [8]. This approach specifically utilized CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 gene polymorphisms and allele activity scores for verification, moving beyond simple phenotype/genotype classifications toward more quantitative metabolic activity terms [8]. This validation confirms that model-based predictions can circumvent the traditional trial-and-error approach in patient treatment, potentially reducing adverse drug reactions and improving therapeutic outcomes.

Comparative analysis shows that models validating against large, diverse datasets (1,914 subjects for the PGx model; 442 cell lines for MOGP) provide more credible evidence for clinical adoption [8] [17]. The MOGP approach offers the distinct advantage of predicting complete dose-response curves rather than single summary metrics (e.g., IC50), enabling more comprehensive efficacy assessment [17]. Furthermore, the MOGP model demonstrated robustness in cross-study testing, maintaining prediction accuracy when trained on limited data—a crucial consideration for rare diseases or understudied populations [17].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Validation Framework for Pharmacogenomic Dosing Models

Experimental Objective: To verify the accuracy of mathematical model-based pharmacogenomic dose predictions against real-world clinical data.

Methodology:

- Data Collection and Curation: The work relied on collecting, extracting, and using real-world data on dosing and patients' genotypes from 26 published studies [8]. A total of 1,914 subjects were included in the validation cohort [8].

- Genetic Focus: The validation specifically focused on drug metabolizing enzymes, with cytochrome CYP450 isoforms CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 gene polymorphisms used for verification [8].

- Model Input Strategy: The validation approach emphasized using simple descriptive metabolic activity terms and allele activity scores for drug dosing rather than traditional phenotype/genotype classifications [8].

- Performance Assessment: The mathematical model's predicted optimal dosing was compared against the reported optimal dosing values from the considered real-world studies [8].

MOGP Model Validation Protocol

Experimental Objective: To assess multi-output Gaussian Process models for predicting dose-response curves across multiple cancer types and with limited training data.

Methodology:

- Data Sources: Dose-response and genomics data were retrieved from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database, including responses to ten drugs across 442 human cancer cell lines representing ten distinct cancer types [17].

- Feature Integration: Three types of molecular features were extracted: genetic variations in cancer genes, copy number alteration status of recurrent altered chromosomal segments, and DNA methylation status of informative CpG islands [17]. Drug chemical features were obtained from PubChem [17].

- Model Architecture: A multi-output Gaussian Process (MOGP) model was implemented to simultaneously predict all dose-responses and uncover biomarkers [17].

- Biomarker Identification: A novel Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence method was applied to measure the importance of each genomic feature from the MOGP predictions [17].

- Validation Approach: Model performance was assessed through cross-cancer-type prediction and training with progressively smaller sample sizes to evaluate robustness with limited data [17].

Visualizing Model Validation Workflows

Pharmacogenomic Model Validation Pathway

Multi-Output Model Comparison Framework

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Dose Prediction Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function in Validation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Data Platforms | Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) | Provides dose-response and genomic data for validation across cancer types [17] | 442 cancer cell lines, 10 cancer types, multi-omics data [17] |

| Chemical Databases | PubChem | Source of chemical features for drugs used in prediction models [17] | Standardized chemical properties and structures |

| Computational Frameworks | Multi-output Gaussian Process (MOGP) | Predicts complete dose-response curves using genomic and chemical features [17] | Models all doses simultaneously; enables biomarker discovery via KL divergence [17] |

| Validation Standards | Real-World Clinical Data (26 studies) | Gold standard for validating model predictions against actual clinical outcomes [8] | 1,914 subjects; CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 polymorphisms [8] |

| Biomarker Discovery | Kullback-Leibler (KL) Divergence | Measures feature importance in MOGP models; identifies novel biomarkers [17] | Identified EZH2 as novel BRAF inhibitor biomarker [17] |

The validation evidence presented establishes that model-based pharmacogenomic dose prediction can successfully forecast optimal dosing when rigorously tested against real-world data. The mathematical model validation with 1,914 subjects and the MOGP cross-cancer validation provide compelling evidence that these approaches can transcend traditional trial-and-error prescribing. For researchers and drug development professionals, this comparative analysis demonstrates that validation must be non-negotiable—the crucial bridge between theoretical models and clinically actionable tools that can safely optimize drug therapy for individual patients.

Exposure-Response, Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Models (NLMEM), and Context of Use

In model-informed drug development (MIDD), the robust prediction of optimal drug doses rests upon three foundational pillars: Exposure-Response (E-R) analysis, which quantifies the relationship between drug exposure and its effects; Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Models (NLMEM), which provide the statistical framework for parsing variability in these relationships across populations; and Context of Use (COU), which defines the specific role and credibility requirements of a model for a given decision. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) M15 guideline defines COU as "a statement that clearly describes the way the model-informed drug development (MIDD) approach will be used and the decisions it will support" [3] [4]. The synergy of these elements is critical for validating pharmacometric models and ensuring their dose predictions are accurate, reliable, and fit for their intended regulatory and clinical purpose.

Defining the Key Terminology

Exposure-Response (E-R)

Exposure-Response analysis is the quantitative examination of the relationship between a defined drug exposure (e.g., dose, concentration, or AUC) and both its effectiveness and adverse effects [1]. It forms the bedrock of dose selection and justification, answering the critical question of how changes in drug exposure influence the probability and magnitude of desired and undesired outcomes.

Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Models (NLMEM)

Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Models are a class of statistical models used to analyze data where the response is nonlinearly related to the parameters and where data are collected from multiple related subjects (e.g., patients, cell lines) [18]. NLMEMs are the gold standard for pharmacometric analysis because they can handle unbalanced, sparse clinical data and account for multiple levels of variability [19]. They distinguish between:

- Fixed Effects: Population-level typical parameter values (e.g., typical clearance in a patient population).

- Random Effects: Quantify the inter-individual (IIV) and inter-occasion variability (IOV) around these typical values, explaining how parameters differ from one subject to another [20].

Context of Use (COU)

The Context of Use is a formalized statement, central to the ICH M15 guideline, that delineates the specific application, decision, and inference supported by the MIDD approach [3] [4]. It is the cornerstone of model credibility assessment, as the validation requirements for a model are entirely dependent on its COU. For instance, a model used to inform a final dosage recommendation on a drug label requires a far more rigorous validation than one used for internal, early-stage candidate selection.

Comparative Roles in Dose Prediction and Model Validation

The table below compares how these three components interact and contribute to the overarching goal of valid dose prediction.

Table 1: Comparative Roles of E-R, NLMEM, and COU in Pharmacometric Dose Prediction

| Component | Primary Role in Dose Prediction | Contribution to Model Validation | Typical Outputs for Decision-Making |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure-Response (E-R) | Quantifies the causal link between drug exposure and clinical outcomes; identifies the target exposure window for efficacy and safety. | Validation focuses on the robustness and clinical plausibility of the inferred relationship (e.g., shape of E-R curve). | Target AUC or Ctrough, optimal dose range, probability of response/toxicity across doses. |

| Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Models (NLMEM) | Provides the structural and statistical framework to characterize population and individual E-R relationships from sparse, real-world data. | Validation assesses model fit (goodness-of-fit plots), predictive performance (VPC), and precision of parameter estimates (confidence intervals). | Population typical parameters, inter-individual variability, covariate effects (e.g., effect of weight on clearance). |

| Context of Use (COU) | Defines the specific dose-related question the model will answer and the regulatory impact of the decision. | Determines the level of evidence and validation needed (e.g., verification, validation, applicability) to deem the model "fit-for-purpose." [1] | A predefined and agreed-upon statement that bounds the model's application and sets criteria for its credible use. |

Experimental Applications and Protocols

The integration of E-R, NLMEM, and a clear COU is demonstrated across diverse drug development scenarios. The following experimental case studies illustrate their application and the critical workflow involved.

Case Study 1: Optimizing Pediatric Dosing with Machine Learning

- Objective: To enhance the precision of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) dosing in pediatric patients with immune-mediated renal diseases by integrating Population PK (PopPK) with machine learning-based E-R analysis [21].

- Protocol:

- Data Collection: Rich pharmacokinetic blood samples were collected from pediatric patients to measure mycophenolic acid (MPA) concentrations.

- PopPK Model Development: A nonlinear mixed-effects model was developed to characterize MPA population pharmacokinetics and identify sources of inter-individual variability (e.g., body weight, albumin levels).

- Exposure-Response Analysis: Individual PK parameters from the PopPK model were used to derive drug exposure metrics (e.g., AUC). Machine learning models (Random Forest, XGBoost) were then trained to predict clinical response based on exposure and patient covariates.

- Dose Prediction & Validation: The final ML model was used to simulate and recommend individualized dosing regimens. Predictive accuracy was validated using metrics like root mean squared error (RMSE) and mean absolute prediction error (MDAPE) [21].

- COU: To support model-informed precision dosing (MIPD) for MMF in a specific pediatric population, enabling dose individualization that improves efficacy and reduces toxicity.

Case Study 2: Identifying Problematic Cancer Cell Lines

- Objective: To identify cancer cell lines (CCLs) that are universally overly sensitive or resistant to drugs, which could skew experimental results in drug screening [18].

- Protocol:

- Data Source: Dose-response data from large-scale studies like the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) and the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC).

- Model Structure: A nonlinear mixed-effects model using a 4-parameter logistic function was fitted to all cell lines for a given drug simultaneously. The model was defined as:

y_ij = E_min + (E_max - E_min) / (1 + exp[H*(log(x_ij) - log(IC_50))]) + e_ij[18] wherey_ijis the response of cell lineiat dosej,x_ijis the drug concentration, andHis the Hill coefficient. The parametersE_min,E_max,IC_50, andHwere modeled with fixed and random effects. - Borrowing Information: The NLMEM framework allowed the response profile of each CCL to be "informed" by the data from all other CCLs, leading to more stable and reliable estimates of the IC50 and other parameters.

- Analysis: The estimated random effects for each cell line were analyzed across multiple drugs. Cell lines with consistently extreme random effects were flagged as universally sensitive or resistant [18].

- COU: To identify and flag specific cancer cell lines that may generate non-generalizable results in in vitro drug discovery screens, thereby improving the quality of preclinical research.

Case Study 3: Integrated Survival and Safety Modeling in Oncology

- Objective: To jointly model longitudinal biomarkers (e.g., tumor size) and time-to-event endpoints (e.g., survival) to optimize dose selection for anticancer drugs [22].

- Protocol:

- Tumor Growth Inhibition (TGI) Model: A nonlinear mixed-effects model characterizes the longitudinal trajectory of tumor size in response to drug exposure and patient-specific covariates.

- Joint Model: The individual parameters from the TGI model (e.g., estimated tumor size reduction at a specific time) are linked to a survival model (e.g., parametric or Cox model) to predict an individual's hazard of disease progression or death.

- Exposure-Response-Safety: This joint modeling framework is simultaneously applied to safety biomarkers or graded adverse events to define the therapeutic window [22].

- Clinical Trial Simulation: The validated joint model is used to simulate virtual clinical trials under different dosing regimens to identify the dose that maximizes the probability of a favorable efficacy-safety balance.

- COU: To integrate all available evidence to support a definitive dose recommendation for Phase 3 trials and drug labeling, particularly for novel oncology therapeutics.

The logical workflow integrating these components in a pharmacometric analysis is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools in Pharmacometrics

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| nlmixr (R package) | An open-source tool for fitting nonlinear PK/PD mixed-effects models [19]. | Used as a credible, free alternative to commercial software (e.g., NONMEM) for model development and simulation. |

| SimBiology (MATLAB) | A commercial modeling and simulation environment for PK/PD and systems pharmacology. | Provides a workflow for NLME model building, parameter estimation, and diagnostic plotting for popPK data [23]. |

| Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM) | A generative stochastic neural network for modeling complex joint distributions in data [24]. | Applied to model multi-item Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and their relationship to drug concentrations. |

| Model Analysis Plan (MAP) | A pre-specified document outlining the objectives, data, and methods for a MIDD analysis [3]. | Critical for regulatory alignment; details the COU, Question of Interest, and technical criteria for model evaluation. |

| Virtual Population | A computationally generated cohort with realistic physiological and genetic diversity [1]. | Used in clinical trial simulations to predict drug exposure and response in subpopulations (e.g., pediatric, renally impaired) before real-world study. |

| Visual Predictive Check (VPC) | A diagnostic plot comparing simulated data from the model to the observed data [19]. | A key method for evaluating the predictive performance of an NLMEM and validating its structure. |

The interplay between Exposure-Response analysis, Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Models, and a well-defined Context of Use creates a rigorous, evidence-based framework for dose prediction in drug development. E-R relationships provide the clinical rationale for dosing, NLMEMs offer the powerful statistical methodology to derive these relationships from complex data, and the COU ensures the entire process is aligned with a specific, credible, and fit-for-purpose goal. Adherence to this triad, as championed by emerging international guidelines like ICH M15, is paramount for enhancing the accuracy and regulatory acceptance of pharmacometric models, ultimately accelerating the delivery of optimally dosed therapies to patients.

Methodologies for Building and Applying Robust Predictive Dose Models

Leveraging Real-World Data and Pharmacogenomics for Personalized Dosing

The integration of real-world data (RWD) and pharmacogenomics (PGx) is transforming the paradigm of personalized dosing from a theoretical concept to a clinically validated practice. This approach moves beyond traditional trial-and-error prescribing by leveraging diverse data sources—including electronic health records (EHRs), genomic databases, and insurance claims—to inform precise medication selection and dosing strategies tailored to individual patient characteristics [25]. The validation of pharmacometric models using real-world evidence (RWE) represents a critical advancement in ensuring these approaches are both accurate and clinically applicable [8] [3].

The growing importance of this field is underscored by the recent International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) M15 guidelines on model-informed drug development (MIDD), which provide a framework for using computational modeling and simulation to inform drug development and regulatory decisions [3]. This review examines the current landscape of RWD and PGx in personalized dosing, focusing on experimental validations, clinical implementations, and the essential tools driving this innovative field forward.

Experimental Validations of PGx-Based Dose Prediction

Mathematical Model Validation with Real-World Clinical Data

Objective: A 2025 study sought to verify the accuracy of mathematical modeling in predicting optimal medication doses based on patient genotypes compared to real-world clinical data [8] [13].

Methodology: The research analyzed real-world dosing and genotype data from 1,914 subjects across 26 studies, focusing on polymorphisms in the CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genes, which encode key drug-metabolizing enzymes [8]. The mathematical model utilized allele activity scores rather than simplistic phenotype classifications to generate more precise dose predictions [8] [13].

Key Findings: The mathematical model successfully predicted the reported optimal dosing values from the considered studies, demonstrating that computational approaches can effectively leverage genetic information to guide therapeutic decisions [8]. This validation underscores the potential of model-based dose prediction to circumvent the traditional trial-and-error approach in pharmacotherapy [8].

Polygenic Contributions to Medication Dosing

Objective: A 2025 longitudinal biobank study investigated both monogenic pharmacogenomic and polygenic contributions to variability in medication dosing [26].

Methodology: Researchers leveraged longitudinal drug purchase data from the Estonian Biobank (N = 212,000) linked with genomic data to derive individual-level daily doses for cardiovascular and psychiatric medications [26]. The study assessed associations with polygenic scores (PGSs) for 16 traits and conducted genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to identify relevant genetic variants [26].

Key Findings:

- Polygenic scores for specific traits were significantly associated with daily doses of common medications: coronary heart disease PGS with statins (β = 0.02, P = 5.9 × 10^(-10)) and systolic blood pressure PGS with metoprolol (β = 0.03, P = 7.5 × 10^(-13)) [26].

- Body mass index PGS was linked to dosing of multiple medications including statins, metoprolol, and warfarin [26].

- GWAS confirmed established PGx signals for metoprolol (CYP2D6) and warfarin (CYP2C9, VKORC1), validating the methodology [26].

- Both polygenic and pharmacogenomic signals contributed independently to dose variability, highlighting the complex genetic architecture underlying drug response [26].

Table 1: Key Experimental Validations of PGx in Personalized Dosing

| Study Focus | Data Source | Sample Size | Key Genes/Variants | Primary Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Model Validation [8] | 26 published studies | 1,914 subjects | CYP2D6, CYP2C19 | Mathematical models accurately predicted reported optimal dosing using allele activity scores |

| Polygenic Contribution [26] | Estonian Biobank | 212,000 individuals | CYP2D6, CYP2C9, VKORC1 + PGS | Both monogenic PGx and polygenic scores independently contribute to dose variability |

| Preemptive PGx Testing [27] | PREPARE Study | 6,944 patients | 12-gene panel | 33% reduction in adverse drug reactions with preemptive PGx testing |

Clinical Implementation and Workflow Integration

Real-World Evidence from Large-Scale Clinical Programs

Several large-scale implementation studies have demonstrated the clinical utility of PGx-enriched personalized dosing:

The PREPARE Study (Preemptive Pharmacogenomic Testing for Preventing Adverse Drug Reactions): This landmark study enrolled 6,944 patients across seven European countries and randomized them to receive either genotype-guided drug treatment or standard care [27]. The intervention group underwent testing for variants in 12 pharmacogenes (CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP3A5, DPYD, F5, HLA-B, SLCO1B1, TPMT, UGT1A1, and VKORC1) guiding prescriptions for 56 commonly used medications [27]. Results demonstrated a significant 33% reduction in clinically relevant adverse drug reactions in the genetically-guided group (21.5% vs. 28.6% in control) [27].

PGx-Enriched Comprehensive Medication Management: A 2022 real-world study of a Medicare Advantage population showed that integrating PGx with comprehensive medication management (CMM) delivered through a clinical decision support system (CDSS) resulted in substantial healthcare improvements [28]. The program demonstrated:

- Reduction of approximately $7,000 per patient in direct medical costs

- Total savings of $37 million across 5,288 enrolled patients compared to 22,357 non-enrolled controls

- A positive shift in healthcare resource utilization away from acute care toward more sustainable primary care options [28]

The RIGHT 10K Study: This large-scale PGx implementation program at Mayo Clinic and Baylor College of Medicine utilized an 84-gene next-generation sequencing panel and found that 99% of participants carried actionable PGx variants in at least one of the five genes examined (SLCO1B1, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, VKORC1, and CYP2D6) [27]. This highlights the near-universal applicability of preemptive PGx testing in clinical populations.

Clinical Workflow Integration

The successful integration of PGx into clinical practice requires a structured workflow that encompasses testing, interpretation, and implementation of results. The following diagram illustrates a generalized clinical implementation workflow validated across multiple studies:

Diagram 1: Clinical implementation workflow for PGx testing, integrating multiple steps from patient identification to outcomes monitoring. CDSS: clinical decision support system; MAP: medication action plan. Adapted from [28] [27].

Medication Utilization and Prioritization

Understanding which medications and genes should be prioritized for PGx testing is essential for efficient clinical implementation. A 2025 scoping review examined real-world utilization rates of medications with clinically important PGx recommendations in older adults (≥65 years) [29].

Table 2: Frequently Prescribed Medications with Actionable PGx Recommendations in Older Adults

| Therapeutic Class | Most Frequently Prescribed Medications | Prescribing Range | Primary Genes Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | Pantoprazole | 0–49.6% | CYP2C19 |

| Cardiovascular | Simvastatin | 0–54.9% | SLCO1B1, CYP3A4 |

| Analgesic | Ondansetron | 0.1–62.6% | CYP2D6 |

| Psychotropic | Various antidepressants | Varies | CYP2D6, CYP2C19 |

| Cardiovascular | Warfarin | Varies | CYP2C9, VKORC1 |

The review analyzed 31 studies and identified 215 unique PGx medications, of which 82 had actionable PGx recommendations according to Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines [29]. The most frequently implicated genes were CYP2D6 (25.6%), CYP2C19 (18.3%), and CYP2C9 (11%) [29]. These findings support the implementation of preemptive panel-based testing over single-gene tests to cover the broad range of clinically relevant pharmacogenes [29].

Regulatory and Payer Perspectives

The adoption of PGx testing in clinical practice is significantly influenced by regulatory frameworks and insurance coverage policies. A 2025 assessment of US payer coverage decisions for PGx testing in psychiatry provides insights into the evidentiary standards considered in reimbursement decisions [30] [31].

Methodology: The study conducted a qualitative and quantitative assessment of publicly available coverage policies from 14 US payers, examining the number, type, and source of citations across policies and coverage decisions [30].

Key Findings:

- Peer-reviewed literature was the most frequently cited source across all policies [30] [31].

- Among 207 peer-reviewed papers cited across all policies, 40% (n = 83) were psychiatry-specific real-world evidence (RWE) studies [30].

- Six psychiatry-specific RWE studies and contributions from 13 distinct sources were frequently cited regardless of payer type or coverage decision [30].

- Coverage determinations appeared to be largely based on how individual payers interpret evidence on the clinical value of testing rather than strictly on the volume of evidence [30] [31].

This analysis highlights the growing importance of RWE in informing coverage decisions and the need for robust real-world studies demonstrating the clinical utility and economic value of PGx testing.

Successful implementation of PGx and RWD approaches requires leveraging specialized databases, analytical tools, and curated knowledge bases. The following table details key resources cited across the reviewed studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for PGx and RWD Studies

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) [29] | Guidelines | PGx clinical guidelines | Evidence-based, peer-reviewed dosing guidelines for specific drug-gene pairs |

| Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB) [29] | Knowledge Base | PGx resource curation | Clinically annotates CPIC guidelines, collects PGx knowledge from literature |

| Estonian Biobank (EstBB) [26] | Data Resource | Longitudinal RWD with genetic data | 212,000 participants with drug purchase data and genomic information |

| Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG) [27] | Guidelines | PGx guidelines | Alternative guideline source with European perspective |

| GeneDose LIVE [28] | Clinical Decision Support | CDSS for medication risk assessment | Integrates genetic and non-genetic risk factors, generates medication action plans |

The integration of real-world data and pharmacogenomics represents a transformative approach to personalized dosing that moves beyond traditional trial-and-error prescribing. Evidence from large-scale clinical implementations, validation studies, and real-world analyses consistently demonstrates that PGx-guided therapy can significantly improve patient outcomes, reduce adverse drug reactions, and generate substantial healthcare savings.

The successful validation of mathematical models against real-world clinical data [8], coupled with growing understanding of both monogenic and polygenic contributions to drug response variability [26], provides a robust foundation for increasingly sophisticated dosing approaches. Furthermore, the development of structured clinical workflows [28] [27] and clearer understanding of medication utilization patterns [29] offers practical pathways for implementation.

As regulatory frameworks continue to evolve [3] and payer coverage increasingly incorporates real-world evidence [30] [31], the field is poised for continued growth and refinement. The ongoing challenge remains in standardizing approaches, demonstrating consistent value across diverse populations, and further validating predictive models to ensure the safe, effective, and equitable implementation of personalized dosing strategies.

In vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection-embryo transfer (ICSI-ET) represent the most widely used assisted reproductive technologies (ART), enabling millions of infertile couples to achieve pregnancy [32]. A pivotal component of successful IVF treatment is controlled ovarian stimulation (COS), which uses follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) to promote the maturation of multiple follicles [32]. The precise determination of the optimal FSH starting dose remains a significant clinical challenge in reproductive medicine.

Historically, FSH dosing followed a "one size fits all" approach, but this has gradually evolved toward individualized treatment strategies [32]. According to ESHRE guidelines, dose individualization can minimize the risks of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), iatrogenic poor ovarian response, and cycle cancellation [32]. Despite the critical importance of precise dosing, clinicians often rely on empirical judgment rather than data-driven models, highlighting the need for standardized, evidence-based dosing tools [32].

This case study examines the development and validation of a multivariate model for predicting optimal FSH starting doses in normal ovarian response (NOR) patients, representing 70-90% of ART cycles worldwide [32]. We analyze the model's performance against clinical standards and alternative approaches, with emphasis on validation within a pharmacometric research framework.

Model Development and Experimental Protocol

Study Population and Design

The prediction model was developed through a retrospective analysis of 535 patients undergoing their first IVF/ICSI-ET cycle at the Reproductive Medicine Department of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University between January 2017 and June 2024 [32]. Patients were randomly divided into a training group (n=317) and a validation group (n=218) in a 6:4 ratio [32].

Inclusion criteria comprised: (1) patients receiving first IVF/ICSI-ET treatment with GnRH agonist or antagonist protocol; (2) age between 20-38 years; (3) regular menstrual cycle (28 ± 7 days); and (4) retrieval of 5-15 oocytes [32]. Exclusion criteria eliminated patients with endocrine diseases, metabolic diseases, autoimmune diseases, or chromosomal abnormalities [32].

Clinical Protocols and Data Collection

All patients underwent controlled ovarian stimulation using either the long-acting GnRH agonist protocol (n=326) or the GnRH antagonist protocol (n=209) [32]. For the agonist protocol, pituitary down-regulation began on day 2-3 of menstruation, followed by COS with exogenous gonadotropin after 28 days. For the antagonist protocol, COS began on cycle day 2-3, with GnRH antagonist added when the leading follicle reached 12-14mm or E2 reached 400pg/ml [32]. Triggering occurred when ≥2 follicles reached ≥18mm diameter [32].

Comprehensive patient data were collected, including:

- Demographics: age, body height, weight, BMI, body surface area

- Reproductive history: infertility duration, type, factors, pelvic surgery history

- Basal hormone levels: FSH, LH, E2, progesterone, prolactin, AMH, testosterone

- Ovarian reserve markers: antral follicle count (AFC)

- Treatment parameters: initial and total Gn dose, stimulation duration [32]

Statistical Analysis and Model Construction

The analytical approach employed both univariate and multivariate linear regression to identify predictive factors influencing the Gn starting dose [32]. Statistically significant predictors (P<0.05) were incorporated into a nomogram for visual representation of the model [32]. Model accuracy was assessed using mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and R² values, with t-tests comparing actual versus predicted Gn starting doses in both training and validation sets [32].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for FSH dose prediction model development

Results: Predictive Performance and Validation

Key Predictors of FSH Starting Dose

Multivariate analysis identified five statistically significant (P<0.05) predictors of the FSH starting dose [32]:

- Patient age

- Body mass index (BMI)

- Basal follicle-stimulating hormone (bFSH)

- Antral follicle count (AFC)

- Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH)

These parameters were incorporated into the final predictive model, which was presented as a clinician-friendly nomogram for determining appropriate Gn starting doses for NOR patients undergoing IVF/ICSI-ET [32].

A separate validation study using the early follicular phase depot GnRH agonist protocol confirmed similar predictive parameters, deriving the following regression equation [33]: Initial FSH dose = 62.957 + 1.780AGE(years) + 4.927BMI(kg/m²) + 1.417bFSH(IU/ml) - 1.996AFC - 48.174*AMH(ng/ml) [33]

Model Performance and Validation

The developed model demonstrated no significant difference (P>0.05) between actual and predicted Gn starting doses in both training and validation groups [32]. Bland-Altman analysis showed excellent agreement in internal validation (bias: 0.583, SD of bias: 33.07IU, 95%LOA: -69.7 to 68.5IU) [33]. External validation further confirmed the model's accuracy (bias: -1.437, SD of bias: 38.28IU; 95%LOA: -80.0 to 77.1IU) [33].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of FSH Dose Prediction Models

| Model Type | Population | Key Predictors | Performance Metrics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate Linear Model [32] [33] | NOR patients | Age, BMI, bFSH, AFC, AMH | No significant difference between actual and predicted doses (P>0.05); Bland-Altman bias: -1.437 to 0.583 | Limited to starting dose prediction |

| Deep Learning CTFE Model [34] | Mixed responders | Static + dynamic treatment data | Dose classification accuracy: 0.737; F1-score: 0.732 | Retrospective, single-center design |

| Popovic-Todorovic Model [32] | Mixed responders | AFC, Doppler score, testosterone, smoking | Limited clinical applicability | Omits age and AMH parameters |

| La Marca Model [32] | Mixed responders | Age, AMH, bFSH | Emphasizes age and AMH importance | Limited predictor variables |

| Howles Model [32] | Mixed responders | bFSH, BMI, age, AFC | Concordance index: 59.5% | Lower predictive accuracy |

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Approaches

Traditional Statistical Models

Earlier prediction models exhibited notable limitations. The Popovic-Todorovic scoring system overlooked critical parameters such as patient age and AMH, significantly restricting its clinical applicability [32]. The Howles model, while pioneering the field with a multifactorial approach, achieved a concordance index of only 59.5% [32].

Advanced Computational Approaches

Recent research has explored more sophisticated modeling techniques. A deep learning framework integrating cross-temporal and cross-feature encoding (CTFE) demonstrated substantial promise for real-time dose adjustment, achieving a dose classification accuracy of 0.737 and significantly outperforming traditional LASSO regression models (F1-score: 0.832 vs 0.699 on day 1) [34].

Optimal control theory applications to superovulation have provided another innovative approach, using moment models of follicle development to predict customized drug dosage regimens [35]. These methods demonstrated potential for increasing follicle count in the desired size range while reducing dosage requirements [35].

Figure 2: Parameter integration in FSH dose prediction models

Discussion: Pharmacometric Implications and Clinical Applications

Validation in Pharmacometric Research Context

The successful validation of this multivariate model for FSH starting dose prediction represents a significant advancement in the application of pharmacometric principles to reproductive medicine. The demonstration of consistent performance across both internal and external validation cohorts [33] provides robust evidence for its predictive accuracy and generalizability.

This approach addresses a critical gap in ART pharmacometrics, where previous models either incorporated only single indicators such as age and FSH, or overlooked key biomarkers like BMI, AFC, and AMH [32]. The comprehensive inclusion of validated predictors aligns with contemporary precision medicine initiatives seeking to optimize therapeutic outcomes while minimizing adverse effects.

Advantages Over Alternative Dosing Strategies

Compared to conventional dosing approaches based primarily on clinician experience, the multivariate model offers several distinct advantages:

- Standardization: Reduces inter-clinician variability in FSH prescribing practices [34]

- Risk Mitigation: Helps prevent both excessive dosing (associated with OHSS) and insufficient dosing (leading to poor ovarian response) [32] [33]

- Efficiency: Potentially reduces the need for dose adjustments during treatment, shortening the time to achieving optimal stimulation [33]

Limitations and Research Directions

Despite its promising performance, the model has several limitations that merit consideration in future research:

- Protocol Specificity: The model was developed and validated primarily in patients undergoing GnRH agonist or antagonist protocols [32], and may require adjustment for other stimulation protocols.

- Population Limitations: The study focused exclusively on normal ovarian responders, limiting generalizability to poor or high responders [32].

- Static Prediction: The model predicts only the starting dose and does not accommodate real-time adjustments based on individual response during stimulation [34].

Future research directions should include:

- Development of dynamic models incorporating real-time treatment response data [34]

- Multi-center prospective validation studies to strengthen generalizability [34]

- Integration of genetic and molecular biomarkers to enhance predictive precision

- Economic analyses evaluating cost-effectiveness compared to standard dosing approaches

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for FSH Dose Prediction Studies

| Reagent/Instrument | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Electrochemiluminescence Immunoassays | FDA/CE-approved platforms | Quantification of AMH, bFSH, LH, E2, progesterone [32] [33] |

| High-Frequency Transvaginal Ultrasound | 7.5MHz+ transducers | Antral follicle count (AFC) and mean ovarian volume measurement [32] [36] |

| Recombinant and Urinary Gonadotropins | Gonal-F, Bravelle, Menopur | Controlled ovarian stimulation protocols [32] [36] |

| GnRH Agonists/Antagonists | Triptorelin, Cetrorelix, Ganirelix | Pituitary suppression for controlled stimulation [32] [37] |

| Electronic Health Record Systems | HIPAA-compliant databases | Retrospective data collection and management [32] [34] |

| Statistical Computing Environments | R (v4.3.1+), Python with scikit-learn | Model development and validation [32] [34] |

This case study demonstrates the successful development and validation of a multivariate model for predicting FSH starting doses in NOR patients undergoing IVF/ICSI-ET. By integrating five key patient parameters—age, BMI, bFSH, AFC, and AMH—the model provides an evidence-based approach to individualizing ovarian stimulation protocols.

The model's validation across internal and external cohorts supports its reliability and suggests potential for broader clinical implementation. When contextualized within pharmacometric dose prediction research, this work represents a meaningful advancement beyond earlier models limited by incomplete predictor variables or restricted populations.

Future research should focus on developing dynamic models that accommodate real-time dose adjustments throughout stimulation, potentially further enhancing the precision and effectiveness of controlled ovarian stimulation in assisted reproduction.

In pharmacometrics, the ability to clearly communicate complex model results is paramount for informing critical drug development and regulatory decisions. Effective visualization bridges the gap between modelers and non-modeler stakeholders, ensuring that insights into covariate effects and model performance are accurately conveyed and acted upon. Traditional diagnostic tools like Visual Predictive Checks (VPCs) and prediction-corrected VPCs (pcVPCs) have served as standard approaches but present significant limitations, particularly when handling heterogeneous data across multiple covariate subgroups. These methods often require extensive data binning and stratification, which can dilute diagnostic power, obscure underlying patterns, and complicate interpretation for multidisciplinary teams [38].

The emergence of the vachette method (variability-aligned, covariate-harmonized effects and time-transformation equivalent) represents a paradigm shift in pharmacometric visualization. This innovative approach enables the intuitive overlay of all observations onto a single, user-selected reference curve while accounting for covariate effects and preserving random effects. By transforming both x- and y-axes to align data across diverse subgroups, vachette provides a cohesive visualization that reveals how a model truly "sees" the data, offering enhanced sensitivity for detecting model misspecification and improving communication efficacy for both modelers and non-modelers [38] [39].

Understanding Traditional Visualization Limitations

Established Diagnostic Methods and Their Shortcomings

Traditional pharmacometric diagnostics rely heavily on simulation-based approaches that segment data for comparison, each with inherent constraints that vachette specifically addresses:

Visual Predictive Checks (VPCs): Compare percentiles (e.g., 5th, 50th, 95th) of observed data against simulated data within specified intervals (e.g., time bins). This approach loses diagnostic power when predictions within a bin differ substantially due to other independent variables (e.g., dose, covariates) or when stratification across covariate groups leads to small sample sizes in each subgroup. The method can particularly fail when high variability causes different curve segments (e.g., peaks and troughs from different subgroups) to be averaged together in the same bin, resulting in loss of original shape information [38].

Prediction-Corrected VPCs (pcVPCs): Mitigate some VPC limitations by normalizing observed and simulated dependent variables to the typical population prediction. However, depending on data sparseness and variability, pcVPCs can still suffer similar drawbacks as traditional VPCs, particularly when sampling is heterogeneous or sample sizes are limited [38].

Transformed Normalized Prediction Discrepancy Error (tnpde): This more recent method retains statistical properties of npde while offering appearance and interpretation similar to VPC. It functions without stratification across wide dose ranges but can lose diagnostic power if reference profile statistics become poor data descriptors due to small sample sizes or sparse, heterogeneous sampling. Crucially, it doesn't scale the independent variable, potentially causing the same limitations as VPC [38].

The Communication Gap in Model Evaluation

These traditional approaches create significant communication challenges throughout the drug development lifecycle. The need for multiple stratified plots, large confidence intervals due to reduced sample sizes, and technical complexity of interpretation often hinder effective communication with multidisciplinary team members who lack specialized modeling expertise. This communication gap becomes particularly problematic when presenting model-based evidence to regulatory authorities or cross-functional decision-makers who must understand how covariate effects influence model predictions and, consequently, dosing recommendations [38] [40].

Table 1: Limitations of Traditional Pharmacometric Visualization Methods

| Method | Primary Approach | Key Limitations | Impact on Dose Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard VPC | Compares percentiles of observed vs. simulated data within bins | Loss of shape information; dilution effects from stratification; obscured covariate effects | Reduced sensitivity to detect model misspecification, potentially compromising dosing recommendations |

| pcVPC | Normalizes data to typical prediction before binning | Limited improvement with sparse data; retains binning artifacts; difficult to interpret | Limited ability to verify covariate impact on exposure, affecting precision in special populations |

| tnpde | Transforms data to retain statistical properties | Dependent on reference profile quality; no independent variable scaling | Potential oversight of timing-related misspecification (e.g., Tmax shifts) critical for dosing intervals |

Core Algorithm and Transformation Process

The vachette method introduces a sophisticated algorithmic approach that transforms both independent and dependent variables to account for covariate effects, enabling all data to be visualized in relation to a single reference profile. The methodology operates through a structured, multi-step process that combines user input with automated transformations [38]:

Model Definition and Covariate Specification: The user defines the pharmacometric model and identifies covariates to be investigated for their effects on the model parameters and predictions.

Model Simulation: The user provides model simulations ("typical predictions") for each observed combination of covariate values, covering the range from first to last observed data point with sufficiently fine resolution.

Reference Selection: The user selects one simulated profile as the "reference," which serves as the baseline for all transformations. This reference can represent a target population (e.g., most frequent covariate value, median continuous covariate) or even an unobserved combination of covariate values.

Automated Landmark Identification: The algorithm automatically identifies characteristic landmarks (minima, maxima, and inflection points) in each simulated profile, using these to split curves into segments between adjacent landmarks. For multi-dose scenarios, each dosing interval is treated as a separate region for landmark detection.

Segment Mapping: Each segment of query curves is transformed to align with corresponding segments of the reference curve through coordinated scaling of both x- and y-axes, effectively mapping query landmarks to reference landmarks.

Observation Transformation: The same transformations applied to query curves are applied to their corresponding observations, preserving the distance between model predictions and observations while accounting for covariate effects.

Landmark Detection and Segment Transformation

The cornerstone of vachette's innovative approach lies in its automated landmark detection system. The algorithm identifies critical points (minima, maxima, inflection points) that define the fundamental structure of each concentration-time or response-profile curve. After identifying landmarks, the algorithm also detects "open ends" - the extremities of simulated curves that aren't themselves landmarks (e.g., the last point of exponential decay) [38].