Time-Kill Kinetics Assay: A Comprehensive Protocol Guide for Antimicrobial Evaluation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the time-kill kinetics assay, a crucial in vitro method for characterizing the bactericidal or bacteriostatic activity of...

Time-Kill Kinetics Assay: A Comprehensive Protocol Guide for Antimicrobial Evaluation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the time-kill kinetics assay, a crucial in vitro method for characterizing the bactericidal or bacteriostatic activity of antimicrobial agents over time. The content spans from foundational principles and standardized protocols, including CLSI and ASTM guidelines, to advanced applications in pharmacodynamic modeling and biofilm studies. It further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, data optimization strategies, and comparative analyses with other antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods. By integrating current methodologies with practical validation techniques, this resource aims to enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of time-kill studies in the discovery and development of novel antimicrobials.

Understanding Time-Kill Kinetics: Core Principles and Significance in Antimicrobial Development

Time-kill kinetics represents a sophisticated in vitro pharmacodynamic method used to quantify the rate and extent of antimicrobial killing over time. Unlike endpoint determinations such as Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), time-kill assays provide a dynamic profile of antimicrobial activity, capturing the complex interaction between a pharmaceutical agent and microorganisms across a temporal landscape [1] [2]. This methodology is particularly valuable in antimicrobial drug development because it reveals the kinetic characteristics of antimicrobial action—whether an agent exerts bactericidal (killing) or bacteriostatic (growth-inhibiting) effects—and can identify potential synergistic combinations of drugs [2].

The fundamental principle underlying time-kill kinetics is the establishment of the rate at which a microorganism population is reduced when exposed to an antimicrobial agent. By measuring survival data at multiple exposure time points, researchers can model the decline in microbial population to potential extinction, providing critical insights for determining optimal dosing regimens and predicting clinical efficacy [3]. This approach offers a more comprehensive understanding of antimicrobial activity compared to single-time-point measurements, as it characterizes the entire progression of microbial kill rates [1].

Key Concepts and Definitions

Bactericidal vs. Bacteriostatic Activity

The classification of antimicrobial activity derived from time-kill kinetics is fundamentally based on the magnitude of microbial reduction:

- Bactericidal Activity: Defined as a greater than 3 log₁₀ decrease in colony-forming units (CFU) of surviving bacteria, which equates to 99.9% killing of the initial inoculum. This level of reduction demonstrates substantial killing capability that is considered clinically significant for eradication of pathogens [2].

- Bacteriostatic Activity: Characterized by a reduction in bacterial growth that does not achieve the 3 log₁₀ threshold, typically maintaining the bacterial population near the starting inoculum level. This indicates inhibition of growth without substantial killing [2].

Table 1: Classification of Antimicrobial Effects Based on Time-Kill Kinetics

| Effect Type | Log Reduction | Percentage Killing | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bactericidal | ≥ 3.0 log₁₀ | ≥ 99.9% | Substantial killing considered clinically significant |

| Bacteriostatic | < 3.0 log₁₀ | < 99.9% | Inhibition of growth without substantial killing |

| Ineffective | No reduction or growth | 0% or negative | No antimicrobial activity demonstrated |

Quantitative Measures in Time-Kill Assays

The quantitative framework of time-kill kinetics relies on logarithmic reductions in viable bacterial counts:

- A 1 log₁₀ reduction represents a 90% decrease in viable organisms (from 1,000,000 to 100,000 CFU/mL)

- A 2 log₁₀ reduction represents a 99% decrease (from 1,000,000 to 10,000 CFU/mL)

- The critical 3 log₁₀ reduction represents a 99.9% decrease (from 1,000,000 to 1,000 CFU/mL) [3]

These quantitative measurements provide a standardized approach to comparing the potency of different antimicrobial agents and regimens, enabling researchers to make precise comparisons between test compounds and establish concentration-effect relationships [2] [4].

Experimental Design and Methodology

Standard Time-Kill Assay Protocol

The execution of a robust time-kill assay requires meticulous attention to protocol details to ensure reproducible and meaningful results. The following workflow outlines the core procedures:

Critical Protocol Steps:

Inoculum Preparation: Challenge bacteria or fungi are suspended generally in 0.9% saline and standardized to a concentration of approximately 1.5 × 10⁶ CFU/mL to ensure consistent starting populations across experimental conditions [1] [3].

Antimicrobial Exposure: The standardized microbial suspension is introduced into the test product, which can be either undiluted (99%) or as a 10% dilution, depending on the experimental design. Multiple treatment modes should be considered, including single agents and combinations to evaluate potential synergistic effects [1].

Sampling and Neutralization: At predetermined time intervals (typically 0, 4, 8, 16, and 24 hours), samples are collected from the suspension and transferred to a validated neutralizing fluid that effectively eliminates the antimicrobial properties of the product without harming surviving microorganisms. This neutralization step is critical for accurate quantification of viable organisms [3].

Viability Assessment: The neutralized suspension undergoes serial dilution (usually 1:10 increments), followed by plating on appropriate agar media. After incubation at 37°C for 24 hours, resulting colonies are counted, with each colony representing a single microorganism that survived antimicrobial exposure [1] [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Time-Kill Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Inoculum | Test organism | Standardized to ~1.5 × 10⁶ CFU/mL in 0.9% saline [1] [3] |

| Antimicrobial Agent | Test compound | Diluted to multiple concentrations (neat or diluted) [3] |

| Neutralizing Fluid | Inactivates antimicrobial agent | Validated for effectiveness per ASTM E1054 [3] |

| Agar Media | Supports microbial growth | Appropriate for test organism (e.g., Nutrient Agar, Sabouraud Dextrose Agar) [5] |

| Dilution Buffers | Serial dilution | Typically 0.9% saline or appropriate buffer [3] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Analysis of Time-Kill Data

The analytical phase of time-kill kinetics transforms raw colony counts into meaningful pharmacodynamic parameters:

Calculation of Viable Bacteria: The number of viable bacteria at each time point is calculated according to the dilution ratio and the counted colonies on the plate. The formula for this calculation is:

[ \text{CFU/mL} = \frac{\text{Number of colonies counted} \times \text{Dilution factor}}{\text{Volume plated (mL)}} ]

These values are then converted to log₁₀ CFU/mL to facilitate comparison and plotting of the time-kill curves [1].

Data Interpretation Framework: The log CFU/mL values for all treatment groups are determined at time 0 and subsequent intervals, enabling the construction of kill curves that visualize the dynamics of antimicrobial activity. The interpretation of these curves follows specific criteria [2]:

- Bactericidal: Reduction of ≥3 log₁₀ CFU/mL from the initial inoculum

- Bacteriostatic: Reduction of <3 log₁₀ CFU/mL, with values remaining near the starting concentration

- Ineffective: No reduction or continued bacterial growth similar to control groups

Visualization and Curve Interpretation

Time-kill data are typically presented as semi-logarithmic plots with time on the x-axis and log₁₀ CFU/mL on the y-axis. The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for interpreting time-kill kinetics results:

Advanced Analytical Approaches

Contemporary time-kill assay methodologies may incorporate multiple readout systems for enhanced data robustness. Recent protocols describe simultaneous quantification using both colony-forming units (CFU) and most probable number (MPN) techniques, particularly for challenging organisms like Mycobacterium tuberculosis [4]. This dual-method approach provides complementary datasets that strengthen the reliability of kill kinetics assessment, especially when dealing with slow-growing or fastidious microorganisms where traditional plating efficiency may be suboptimal.

Longitudinal data from time-kill assays reflect the dynamics of antibiotic effects over time against planktonic cultures and enable quantification of the concentration-effect relationship, which is fundamental to pharmacodynamic modeling and dose optimization [4].

Applications in Antimicrobial Research

Time-kill kinetics assays have become indispensable tools across multiple domains of antimicrobial research and development:

Natural Product Evaluation: Time-kill kinetics has been extensively employed to characterize antimicrobial properties of natural products. For example, in a study investigating mushroom extracts, time-kill kinetics revealed that methanol extracts of Trametes gibbosa, Trametes elegans, Schizophyllum commune, and Volvariella volvacea exhibited primarily bacteriostatic action against test organisms, providing crucial information about their mechanism of antimicrobial activity [5].

Novel Antimicrobial Peptide Assessment: In the development of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), time-kill assays have confirmed rapid bactericidal action of promising candidates. For instance, the peptide Hel-4K-12K demonstrated complete bacterial elimination within one hour at its MIC concentration, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic agent against resistant bacteria [6].

Synergistic Combination Studies: Time-kill kinetics is particularly valuable for evaluating potential synergistic effects between antimicrobial agents. Studies designed with multiple treatment modes (single agents alone versus combinations) can identify enhanced killing kinetics that support combination therapy approaches for multidrug-resistant infections [1].

Regulatory Considerations and Guidelines

The execution of time-kill assays for regulatory purposes must adhere to established methodological standards:

- CLSI Guidelines: The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute provides standardized methodology for time-kill kinetics assays of antimicrobial agents through document M26 [2].

- ASTM Standards: For antimicrobial agents requiring shorter time-kill analysis (seconds/minutes), such as antiseptics, the ASTM E2315 guideline provides appropriate methodology [2].

- Neutralization Validation: Critical to assay validity, neutralization methods must be properly validated according to standards such as ASTM E1054 to ensure accurate assessment of microbial survival [3].

These standardized approaches ensure that time-kill data generated in different laboratories maintain comparability and reliability, supporting informed decisions in antimicrobial drug development and regulatory evaluations.

Table 3: Regulatory Guidelines for Time-Kill Assays

| Guideline | Scope/Application | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CLSI M26 | Antimicrobial agents | Standardized methodology for time-kill kinetics [2] |

| ASTM E2315 | Antimicrobial agents with short kill times | Methodology for seconds/minutes kill time analysis [2] |

| ASTM E1054 | Neutralization validation | Standards for validating neutralization methods [3] |

| EN Methods | General time-kill aqueous suspension tests | European standardized methodology [3] |

In antimicrobial research, the classification of agents as either bactericidal or bacteriostatic is fundamental for understanding their mode of action and potential clinical application. Bactericidal agents directly kill bacteria, leading to a irreversible reduction in bacterial viability, while bacteriostatic agents reversibly inhibit bacterial growth and reproduction, relying on the host's immune system to clear the infection [7] [8]. The time-kill kinetics assay serves as a critical in vitro tool for characterizing this activity over time, providing dynamic data beyond what is available from endpoint measurements like Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) [2] [9].

The interpretation of a ≥3 log₁₀ (99.9%) reduction in Colony Forming Units per milliliter (CFU/mL) is the established laboratory benchmark for defining bactericidal activity [7] [2]. This quantitative measure distinguishes agents that kill from those that merely inhibit. However, this classification is not always absolute; it can be influenced by factors such as bacterial species, inoculum size, antimicrobial concentration, and exposure time [7]. For instance, some antibiotics like linezolid exhibit bactericidal activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae but are bacteriostatic against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) [7].

Theoretical Framework and Definitions

Key Parameters and Quantitative Measures

The following table summarizes the core laboratory parameters used to define and distinguish bactericidal and bacteriostatic activity.

Table 1: Key Definitions and Quantitative Measures for Antimicrobial Activity

| Parameter | Definition | Interpretation and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) | The lowest concentration of an antimicrobial that inhibits visible bacterial growth after 24 hours of incubation in specific media [7]. | Defines the potency of an antimicrobial. It is a primary measure for both bacteriostatic and bactericidal agents. |

| Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) | The minimum concentration of an antimicrobial required to achieve a ≥99.9% (3 log₁₀) reduction in the initial bacterial inoculum after 24 hours [7]. | Confirms bactericidal activity. The MBC/MIC ratio is used to classify an agent's action. |

| MBC/MIC Ratio | A ratio comparing the MBC to the MIC of an antimicrobial agent [7]. | ≤4: Classified as Bactericidal. >4: Classified as Bacteriostatic [7]. |

| ≥3 log₁₀ Reduction in CFU/mL | Equivalent to a 99.9% kill rate of the initial bacterial inoculum [2] [3]. | The standard threshold for defining bactericidal activity in time-kill kinetics assays. |

The Logic of Classifying Antimicrobial Action

The decision tree below outlines the standard workflow for classifying an antimicrobial agent as bactericidal or bacteriostatic based on data from time-kill kinetics assays and MBC/MIC ratios.

Time-Kill Kinetics Assay: A Detailed Protocol

The time-kill kinetics assay is a suspension test that measures the rate and extent of killing of a microorganism by an antimicrobial agent over a defined period, typically 24 hours [3]. It provides a time-course profile of antimicrobial effect, which is more informative than a single time-point test.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Time-Kill Kinetics Assay

| Item | Function and Specification |

|---|---|

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CAMHB) | Standardized growth medium for the assay, ensuring consistent ion concentration for antibiotic activity [9]. |

| Sterile Saline (0.9%) | Diluent for preparing bacterial suspensions and performing serial dilutions [3]. |

| Antimicrobial Stock Solutions | Solutions of test compounds at high concentration (e.g., 1-10 mg/mL) in appropriate solvent (e.g., water, DMSO) [9] [10]. |

| Neutralizing Fluid | Used to terminate antimicrobial action at specific time points; must be validated for the specific antimicrobial being tested (e.g., Dey-Engley broth) [3]. |

| Agar Plates (e.g., Mueller-Hinton Agar) | Used for pour-plating or spread-plating to enumerate viable bacteria (CFU) [5] [3]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Preparation of Inoculum

- Grow the bacterial strain of interest to the mid-logarithmic phase (typically 4-6 hours of growth) [9].

- Adjust the turbidity of the bacterial suspension to a 0.5 McFarland standard, which corresponds to approximately 1-2 x 10⁸ CFU/mL [9] [10].

- Dilute the suspension in the chosen broth to achieve a final inoculum density of approximately 5 x 10⁵ to 1 x 10⁶ CFU/mL in the test vessel [10].

Step 2: Preparation of Antimicrobial Solutions

- Prepare working solutions of the test antimicrobial at concentrations that are multiples of the predetermined MIC (e.g., 0.5x, 1x, 2x, 4x MIC) [9].

- Include two essential controls:

- Growth Control: Inoculated broth without any antimicrobial agent.

- Vehicle Control: Inoculated broth with the solvent used to dissolve the antimicrobial (e.g., DMSO) to rule out solvent toxicity [10].

Step 3: Incubation and Sampling

- Combine the standardized inoculum with the antimicrobial solutions in flasks and incubate at 37°C with constant shaking [9].

- At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 hours), aseptically remove aliquots (e.g., 1 mL) from each flask [2] [9].

Step 4: Quantification of Viable Bacteria

- Immediately after sampling, serially dilute the aliquots in sterile saline or a neutralizing broth to stop the antimicrobial action [3].

- Plate appropriate dilutions (e.g., 100 µL) onto agar plates via spread-plating or pour-plating [5] [3].

- Incubate the plates for 18-24 hours at 37°C and count the resulting colonies.

Step 5: Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Calculate the bacterial density (log₁₀ CFU/mL) for each sample at each time point.

- Plot the log₁₀ CFU/mL against time to generate time-kill curves for each concentration of the antimicrobial and for the controls.

- Interpretation:

- Bactericidal Activity: A decrease of ≥3 log₁₀ CFU/mL from the initial inoculum at any time point [2].

- Bacteriostatic Activity: The log₁₀ CFU/mL remains relatively unchanged or decreases by less than 3 log₁₀ CFU/mL compared to the initial inoculum [5] [2].

- Bacterial Regrowth: An initial decrease followed by an increase in CFU, which may indicate degradation of the antibiotic or the emergence of resistance.

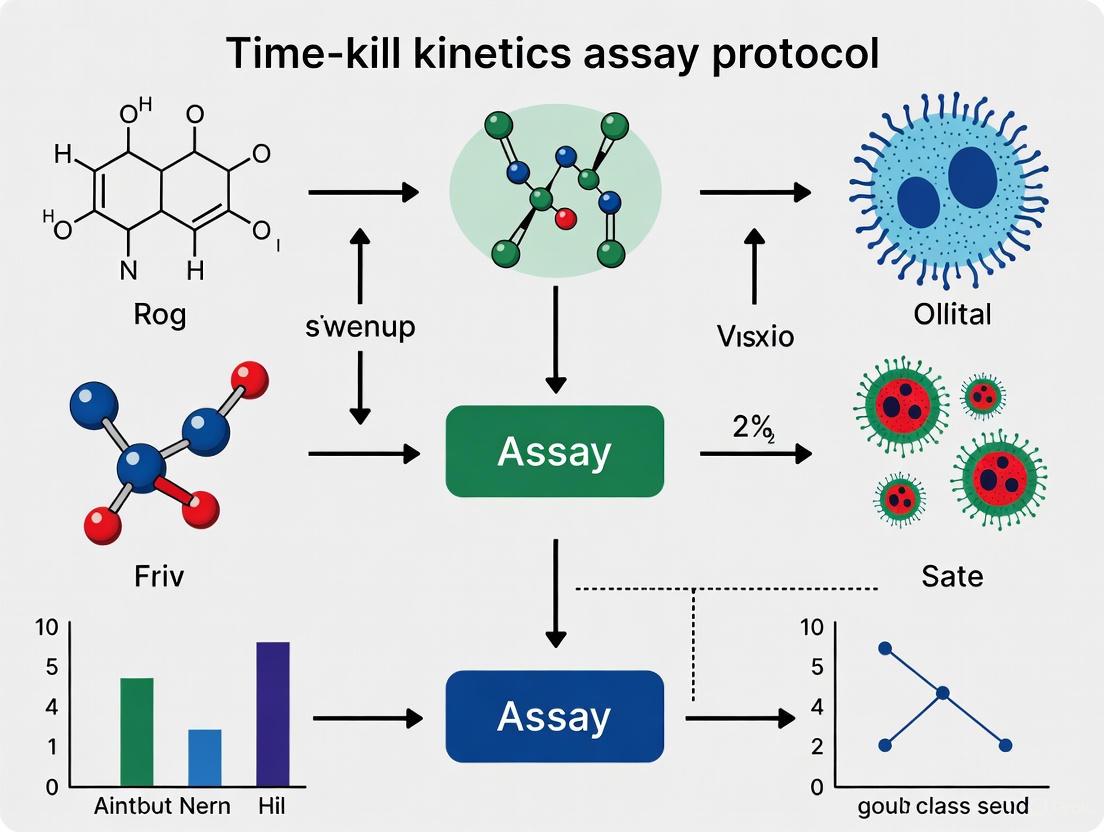

The following diagram visualizes the key stages of the experimental protocol and the subsequent data analysis pathway.

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Practical Examples from Research

Time-kill kinetics provide concrete data for classifying antimicrobials. The following table summarizes findings from recent studies, illustrating how this assay determines an agent's action.

Table 3: Empirical Data from Time-Kill Kinetics Studies

| Antimicrobial Agent / Extract | Test Organism(s) | Key Findings from Time-Kill Assay | Classification | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol extract of Trametes gibbosa | Various Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria | The extracts limited bacterial growth but did not achieve a ≥3 log₁₀ reduction in viable cell count. | Bacteriostatic [5] | [5] |

| Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Achieved ≥99.9% (3 log₁₀) reduction in the number of viable cells at 24 hours post-inoculation at 1x MIC concentration. | Bactericidal [9] | [9] |

| Levofloxacin (LEV) | Salmonella typhi ST07 | Achieved a 3 log₁₀-fold reduction in CFU/mL at 30 hours post-inoculation at 1x MIC concentration. | Bactericidal [9] | [9] |

| Ofloxacin (OFL) | Enterobacter aerogenes EA01 | Achieved a 3 log₁₀-fold reduction in CFU/mL at 30 hours post-inoculation at 1x MIC concentration. | Bactericidal [9] | [9] |

| Phosphanegold(I) Dithiocarbamate (Compound 4) | MRSA and Bacillus sp. | Showed varying degrees of bactericidal and bacteriostatic activities against different susceptible strains. | Context-Dependent [10] | [10] |

Factors Influencing Activity and Clinical Translation

It is critical to recognize that the classification derived from in vitro time-kill assays does not always directly translate to clinical superiority. The in vitro activity can be influenced by several factors [7]:

- Bacterial Strain and Species: An antibiotic may be bactericidal against one species but bacteriostatic against another (e.g., linezolid is bactericidal against Streptococcus pneumoniae but bacteriostatic against enterococci) [7].

- Antibiotic Concentration and Dosing: The achieved concentration at the site of infection, dictated by pharmacokinetics (PK), is a major determinant of in vivo efficacy.

- Inoculum Effect: A high density of bacteria can significantly reduce the apparent efficacy of some antimicrobials.

- Interaction with the Host Immune System: Bacteriostatic agents work in concert with the host's immune defenses to clear an infection, which is not a factor in in vitro assays [7] [8].

Furthermore, the long-held dogma that bactericidal drugs are inherently superior to bacteriostatic ones, especially in severe infections, is being re-evaluated. Specific bacteriostatic agents like linezolid and tigecycline have demonstrated clinical non-inferiority to bactericidal agents for infections such as pneumonia, intra-abdominal infections, and skin and soft tissue infections [7].

In the field of antimicrobial research, the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) serve as fundamental in vitro parameters for evaluating the potency of antimicrobial agents. The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent that inhibits visible growth of a microorganism after a standard incubation period (typically 16-20 hours for fast-growing bacteria), while the MBC represents the lowest concentration that kills ≥99.9% of the initial bacterial inoculum [11] [12]. These parameters provide a crucial foundation for understanding antimicrobial efficacy; MIC distinguishes between growth inhibition and resistance, whereas MBC helps differentiate bacteriostatic (inhibitory) from bactericidal (lethal) effects [11] [13]. Concurrently, time-kill curve (TKC) analysis extends beyond these static endpoint measurements by characterizing the rate and extent of microbial killing over time, providing dynamic, time-dependent pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) data that more accurately reflects antimicrobial action under conditions mimicking in vivo environments [14] [15].

The relationship between these parameters forms a hierarchical framework for antimicrobial assessment: MIC establishes the threshold for biological activity, MBC confirms lethal potential, and time-kill curves elucidate the kinetics of the entire interaction, from initial inhibition to ultimate eradication or regrowth. This integrated approach is particularly valuable for profiling novel antimicrobial candidates, optimizing dosing regimens, and identifying combinations that overcome resistance mechanisms [11] [14].

Theoretical Framework and Relationships

Conceptual Hierarchy of Antimicrobial Testing Parameters

The evaluation of antimicrobial agents follows a logical progression from simple threshold determinations to complex kinetic profiling. MIC testing serves as the initial screening step, identifying whether a compound possesses any inhibitory activity and establishing the concentration required to suppress visible growth [16]. This binary classification (growth vs. no growth) provides a practical foundation for further investigation but reveals nothing about the temporal dynamics or killing efficiency of the antimicrobial agent.

Building upon MIC data, MBC determination differentiates between compounds that merely inhibit growth (bacteriostatic agents) and those that achieve microbial death (bactericidal agents). The MBC/MIC ratio provides valuable insights into an agent's killing characteristics – a ratio ≤4 generally indicates bactericidal activity, while higher ratios suggest bacteriostatic activity [13]. This distinction has profound clinical implications, as bactericidal agents are often preferred for treating endocarditis, meningitis, and infections in immunocompromised patients where host defenses may be inadequate to eliminate pathogens.

Time-kill curve analysis represents the most comprehensive of these approaches, capturing the temporal dynamics of microbial killing that static endpoint measurements cannot reveal. Unlike MIC/MBC determinations that provide single-timepoint snapshots, TKCs generate a continuous profile of microbial response to antimicrobial exposure, enabling researchers to distinguish between concentration-dependent killing (where higher concentrations produce greater killing rates) and time-dependent killing (where the duration of exposure above MIC correlates with efficacy) [14] [15]. This kinetic information proves invaluable for establishing optimal dosing strategies and identifying compounds with persistent effects that continue to suppress regrowth even after concentrations fall below MIC.

Figure 1: The hierarchical relationship between MIC, MBC, and time-kill curves in antimicrobial evaluation, progressing from basic inhibition assessment to dynamic killing profiling and resistance prediction.

Methodological Synergies and Information Complementarity

These parameters exhibit significant methodological synergy, with each approach compensating for limitations in the others. While MIC testing offers high-throughput screening capability, it cannot distinguish between bactericidal and bacteriostatic effects, potentially overlooking compounds with slow but ultimately complete killing kinetics [11]. MBC testing addresses this limitation but remains vulnerable to artifacts from drug carryover during subculturing and provides no information about killing rates [12]. Time-kill curves overcome these constraints by directly monitoring microbial viability throughout the exposure period, enabling detection of biphasic killing patterns (indicating heteroresistance or persistence) and delayed regrowth that signals emerging resistance [14].

The integration of these approaches creates a powerful framework for comprehensive antimicrobial characterization. MIC values guide appropriate concentration selection for time-kill studies, while MBC determinations validate whether observed inhibition translates to meaningful microbial death. Conversely, time-kill curves provide context for interpreting MIC/MBC results – for instance, explaining why two agents with identical MIC values might demonstrate markedly different clinical efficacy due to variations in their killing kinetics or post-antibiotic effects [15].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Broth Microdilution for MIC Determination

The broth microdilution method represents the gold standard for MIC determination, providing reproducible, quantitative results that align with clinical microbiology practices [16]. The following protocol, adapted from EUCAST guidelines, details the procedure for non-fastidious organisms:

Day 1: Bacterial Strain Preparation

- Using a sterile 1 μL loop, streak all test strains on LB agar (or appropriate rich medium supplemented with necessary antibiotics for selection).

- Incubate plates statically overnight at 37°C.

Day 2: Inoculum Standardization

- Gently vortex the overnight cultures.

- Mix 100 μL of overnight culture with 900 μL growth media and measure OD600 using a spectrophotometer.

- Calculate the volume of overnight culture needed to prepare standardized inoculum using the formula: Volume (μL) = 1000 μL ÷ (10 × OD600 measurement)/(target OD600)

- Pipette the calculated volume into a sterile 1.5 mL microtube and add 0.85% w/v sterile saline solution to 1 mL total volume.

- Use inoculum within 30 minutes of preparation [16].

MIC Assay Setup

- Prepare serial two-fold dilutions of the antimicrobial agent in Mueller-Hinton broth (or appropriate medium) in 96-well microtiter plates. Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth is recommended for testing cationic antimicrobials like polymyxins [16].

- Add standardized bacterial inoculum (5 × 10^5 CFU/mL final concentration) to all wells except sterility controls.

- Include growth control wells (inoculum without antimicrobial) and sterility controls (medium only).

- Incubate plates at 37°C for 16-20 hours (adjust for slow-growing organisms if necessary).

- Record MIC as the lowest antimicrobial concentration showing no visible turbidity [16] [12].

Quality Control

- Perform CFU enumeration to verify inoculum density by serial dilution and spot plating.

- Include quality control strains with known MIC ranges (e.g., E. coli ATCC 25922) in each assay run.

- Conduct tests in biological triplicate on different days to ensure reproducibility for research purposes [16].

MBC Determination Protocol

The MBC determination builds directly upon MIC results:

Subculturing Procedure

- From all clear wells in the MIC plate (showing no visible turbidity), subculture 100 μL onto appropriate non-selective agar plates (e.g., blood agar for fastidious organisms).

- Use a sterile bent rod to evenly spread the aliquot across the agar surface.

- Incubate subculture plates at 37°C for 24 hours.

MBC Interpretation

- Examine subculture plates for bacterial growth.

- The MBC is defined as the lowest antimicrobial concentration that results in no visible colony formation or yields ≤0.1% of the original inoculum (equivalent to ≥99.9% killing) [12] [13].

- Calculate the MBC/MIC ratio to classify antimicrobial activity: ratio ≤4 suggests bactericidal activity, while ratio >4 indicates bacteriostatic activity [13].

Time-Kill Curve Assay Methodology

Time-kill curves provide kinetic data on bacterial killing and are essential for comprehensive antimicrobial characterization:

Experimental Setup

- Prepare antimicrobial solutions at multiple concentrations (typically 0.5×, 1×, 2×, and 4× MIC) in appropriate culture medium.

- Inoculate flasks containing antimicrobial solutions with standardized bacterial suspension (5 × 10^5 CFU/mL final concentration).

- Include growth control flasks (inoculum without antimicrobial).

- Incubate at 37°C with constant shaking.

Sampling and Enumeration

- Remove samples (e.g., 100 μL) from each flask at predetermined timepoints (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24 hours).

- Perform serial 10-fold dilutions in neutralizer solution or saline to minimize antibiotic carryover.

- Plate appropriate dilutions onto agar media and incubate for 18-24 hours at 37°C.

- Enumerate colony-forming units (CFU/mL) and plot log10 CFU/mL versus time [14] [15].

Data Interpretation

- Bactericidal activity: ≥3 log10 reduction (99.9% killing) in CFU/mL compared to initial inoculum.

- Bacteriostatic activity: <3 log10 reduction in CFU/mL.

- Regrowth: Initial reduction followed by increase in bacterial counts, suggesting emerging resistance or adaptive tolerance.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for time-kill curve assays, illustrating the sequential steps from bacterial preparation through data visualization for kinetic analysis of antimicrobial activity.

Data Presentation and Interpretation

Quantitative Comparison of Antimicrobial Parameters

Table 1: MIC and MBC values for representative antimicrobial agents against bacterial pathogens

| Antimicrobial Agent | Bacterial Strain | MIC Value | MBC Value | MBC/MIC Ratio | Interpretation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyper-branched poly-L-lysine (HBPL) | MRSA ATCC 43300 | 0.5 mg/mL | 1.0 mg/mL | 2 | Bactericidal | [13] |

| Methylene Blue (MB) with photoactivation | E. faecalis ATCC 29212 | 66.67 ± 28.87 μg/mL | 266.67 ± 115.47 μg/mL | 4 | Bactericidal | [12] |

| MB-rGO with photoactivation | E. faecalis ATCC 29212 | 50.00 ± 0.00 μg/mL | 200.00 ± 0.00 μg/mL | 4 | Bactericidal | [12] |

| Grapefruit Extract | S. aureus | 0.25 ± 0.08 mg/mL | ND | - | - | [11] |

| Erythromycin | S. aureus | 0.0008 ± 0.0003 mg/mL | ND | - | - | [11] |

Table 2: Time-kill curve parameters for antimicrobial agents in different media conditions

| Antimicrobial Agent | Bacterial Strain | Media Condition | Time to 99.9% Killing | Regrowth Observed | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cefazolin | Model pathogen | Pure MHB | 6h | No | Standard growth | [14] |

| Cefazolin | Model pathogen | MHB + 20% plasma | Delayed by 0.25h | No | Growth delay observed | [14] |

| Cefazolin | Model pathogen | MHB + 70% plasma | Delayed by 2.90h | No | Significant growth delay | [14] |

| Clindamycin | Model pathogen | Pure MHB | 8h | No | Standard growth | [14] |

| Clindamycin | Model pathogen | MHB + 20% plasma | Delayed by 0.64h | No | Growth delay observed | [14] |

| Clindamycin | Model pathogen | MHB + 70% plasma | Delayed by 1.40h | No | Significant growth delay | [14] |

Advanced Applications and Integration with Novel Technologies

Bioluminescence-Based Real-Time Monitoring Recent advances in antimicrobial susceptibility testing incorporate bioluminescent bacterial strains engineered with reporter genes (e.g., bacterial luciferase) for real-time viability assessment. This approach offers several advantages over traditional methods:

- Continuous monitoring without manual sampling

- Enhanced sensitivity to sublethal effects

- Non-invasive measurement preserving sample integrity

- Reduced assay time through early detection of inhibition or killing

Studies demonstrate strong correlation between bioluminescence signals and classical CFU enumeration in MIC/MBC determinations, validating this approach for rapid antimicrobial screening [15]. The methodology involves:

- Using naturally luminescent bacteria or strains transformed with lux operons

- Measuring bioluminescence kinetics alongside optical density

- Establishing correlation between light emission and viable counts

- Applying real-time data for pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling

Addressing Methodological Limitations Standard MIC/MBC methods face challenges when testing non-conventional antimicrobials with unique physicochemical properties (e.g., natural extracts, ionic liquids, ozonated oils, nanoparticulate systems). These substances may exhibit:

- Poor solubility in aqueous testing media

- Interaction with medium components

- High viscosity affecting diffusion

- Volatility impacting concentration stability

For such compounds, a combined methodological approach is recommended, integrating broth microdilution with agar dilution and disk diffusion to confirm activity despite methodological limitations [11]. Additionally, modifications to standard protocols may be necessary, such as:

- Using cation-adjusted media for testing cationic antimicrobial peptides

- Incorporating solubilizing agents for hydrophobic compounds

- Implementing low-volume assays for scarce investigational compounds

- Applying specialized detection methods for turbidity-masking substances [16]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for MIC, MBC, and time-kill curve assays

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Application/Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mueller-Hinton II Broth | Cation-adjusted | Standardized growth medium for susceptibility testing | [15] |

| 96-well Microtiter Plates | Sterile, polystyrene | Broth microdilution MIC assays | [16] [12] |

| Diode Laser | 660 nm wavelength | Photoactivation of photosensitizers in aPDT studies | [12] |

| Bioluminescent Bacterial Strains | e.g., P. aeruginosa Xen41, S. aureus SAP229 | Real-time viability assessment without sampling | [15] |

| Sheep Blood Agar | 5% defibrinated sheep blood | Subculturing for MBC determination and purity checks | [12] |

| Hyper-branched Poly-L-lysine | MW 3,114-4,532 Da, PDI 1.46 | Synthetic antimicrobial polymer for novel agent studies | [13] |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide Functionalized MB | 12.5-400 μg/mL range | Enhanced photosensitizer for antimicrobial photodynamic therapy | [12] |

| Human Plasma | 20-70% concentration in MHB | Physiologically relevant media for improved in vitro-in vivo correlation | [14] |

The integrated application of MIC, MBC, and time-kill curve analyses provides a comprehensive framework for antimicrobial efficacy assessment that transcends the limitations of any single approach. While MIC establishes fundamental inhibitory concentrations and MBC confirms lethal potential, time-kill curves elucidate the kinetic profile essential for predicting in vivo efficacy and designing optimal dosing regimens. The continued refinement of these methodologies – through incorporation of physiologically relevant media conditions, advanced detection technologies like bioluminescence reporting, and adaptations for non-conventional antimicrobial agents – will enhance their predictive value in the translational pipeline. For researchers engaged in antimicrobial discovery and development, this multi-parametric approach offers the robust dataset necessary to advance promising candidates from laboratory characterization to clinical application in an era of escalating antimicrobial resistance.

The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) is a cornerstone of antimicrobial susceptibility testing, defined as the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent that prevents visible growth of a microorganism after overnight incubation [17]. Despite its widespread use and high reproducibility, the static nature of MIC determination presents significant limitations. As a single endpoint measurement, MIC fails to capture the dynamic interactions between antibiotics and bacteria over time, obscuring critical pharmacodynamic (PD) information such as the rate and extent of bacterial killing, which are essential for predicting clinical efficacy [18] [19].

Time-kill kinetics assays address these limitations by providing a comprehensive, dynamic profile of antimicrobial activity against bacterial populations over time. This method quantifies the rate and extent of bactericidal or bacteriostatic activity, enabling researchers to distinguish between different killing patterns and understand the time- and concentration-dependent characteristics of antimicrobial agents [2] [19]. Unlike static MIC determinations, time-kill kinetics can identify whether an antimicrobial exhibits concentration-dependent killing (where higher concentrations result in greater killing) or time-dependent killing (where the duration of exposure is more critical than peak concentration), thereby facilitating the optimization of dosing regimens for pre-clinical development [20] [18].

Limitations of Static MIC Determinations

Fundamental Constraints of the MIC Assay

The MIC value, while simple to determine, provides an incomplete picture of antimicrobial efficacy due to several inherent constraints. Firstly, MIC testing employs a fixed incubation period (typically 16-20 hours) and static antibiotic concentrations, which do not reflect the constantly changing drug levels experienced by pathogens in vivo due to pharmacokinetic processes of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion [19]. This static exposure fails to model the dynamic nature of antibiotic concentrations in human tissues and bodily fluids, potentially leading to inaccurate predictions of clinical effectiveness.

Secondly, the MIC represents a population-level threshold that obscures heterogeneous responses within bacterial populations. It does not account for the presence of persister cells or resistant subpopulations that may influence treatment outcomes, particularly with bactericidal agents [18]. Furthermore, the MIC endpoint is based on visible growth inhibition, which lacks precision in quantifying the extent of bacterial killing or determining whether the antimicrobial effect is primarily bactericidal (killing) or bacteriostatic (growth inhibition) [19].

Clinical Relevance and Predictive Value Gaps

The clinical translation of MIC data is complicated by numerous factors that limit its predictive value for treatment success. MIC testing in artificial media often fails to account for the influence of host factors, including immune system interactions, protein binding, and site-specific penetration barriers that alter antibiotic bioavailability at the infection site [19]. Additionally, the inoculum effect, where high bacterial densities can significantly reduce antibiotic effectiveness, is not routinely assessed in standard MIC determinations but can profoundly impact therapeutic outcomes [19].

Perhaps most importantly, MIC values alone provide insufficient information for optimizing dosing regimens, as they do not characterize the kinetics of antimicrobial activity [18]. Different antibiotics with similar MIC values may exhibit dramatically different time-kill profiles, necessitating distinct dosing strategies to maximize efficacy and minimize resistance development. This limitation becomes particularly critical when treating infections in immunocompromised patients, where rapid bactericidal activity is essential for successful outcomes [19].

Advantages of Time-Kill Kinetics

Capturing Dynamic Antimicrobial Effects

Time-kill kinetics assays provide a comprehensive temporal profile of antimicrobial activity that reveals critical pharmacodynamic information unavailable through static MIC testing. This methodology enables researchers to quantitatively monitor the progression of bacterial killing over time, characterizing both the rate of kill and the extent of kill at various antibiotic concentrations [2] [19]. By capturing these dynamic effects, time-kill kinetics can distinguish between bactericidal agents (which achieve ≥3 log₁₀ reduction in colony-forming units [CFU]/mL) and bacteriostatic agents (which inhibit growth without achieving this level of killing) [2] [3].

This approach is particularly valuable for identifying concentration-dependent killing patterns, where increased antibiotic concentrations result in enhanced killing rates and extent, as seen with aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones [20] [18]. Conversely, time-kill kinetics also reveals time-dependent killing patterns, where antibacterial activity primarily depends on the duration of exposure above a threshold concentration, characteristic of β-lactams and macrolides [20]. This discrimination is crucial for designing optimal dosing regimens, as concentration-dependent antibiotics benefit from higher peak concentrations, while time-dependent antibiotics require prolonged exposure above the MIC [20] [18].

Enhanced Predictive Capability for In Vivo Efficacy

The dynamic nature of time-kill kinetics data enables more accurate predictions of in vivo efficacy by facilitating the development of mechanistic pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) models [21]. These models integrate time-kill data with pharmacokinetic parameters to simulate bacterial response under fluctuating antibiotic concentrations, mirroring the dynamic environment encountered in infected patients [18] [21]. Such modeling approaches have demonstrated that bacterial susceptibility to an antibiotic cannot be adequately described by MIC alone, as isolates with identical MIC values may exhibit different maximal kill rates (Emax) and concentration-response relationships (Hill coefficient) [18].

Time-kill kinetics also provides critical insights for suppressing resistance emergence by characterizing the mutant selection window and identifying concentrations that prevent the amplification of resistant subpopulations [19]. Furthermore, this approach is indispensable for evaluating antibiotic combination therapies, as it can detect synergistic, additive, or antagonistic interactions between drugs that would remain undetected in static MIC assays [19]. The enhanced predictive capability of time-kill kinetics makes it particularly valuable for guiding antibiotic therapy in immunocompromised patients and for infections requiring rapid bactericidal activity, such as meningitis and endocarditis [19].

Experimental Protocols

Standard Time-Kill Kinetics Assay Protocol

The time-kill kinetics assay evaluates the bactericidal or bacteriostatic activity of antimicrobial agents over a defined period, typically 24 hours. The following protocol adheres to guidelines established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and incorporates best practices from current literature [2] [19].

Materials and Reagents:

- Test microorganisms (freshly cultured, 18-24 hours)

- Antimicrobial agents (pure substances of known potency)

- Appropriate culture media (e.g., Mueller-Hinton Broth [MHB])

- Sterile saline (0.9% NaCl) for dilutions

- Neutralizing solution (e.g., Dey-Engley neutralizing broth)

- Agar plates for colony counting

- Incubator set at appropriate temperature (e.g., 35±2°C)

- Water bath (for temperature control)

Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Adjust the turbidity of a fresh bacterial culture in logarithmic growth phase to approximately 1×10⁸ CFU/mL (0.5 McFarland standard), then dilute in culture medium to achieve a final inoculum of 1×10⁶ CFU/mL in the test system.

Antibiotic Solution Preparation: Prepare serial dilutions of the antimicrobial agent in culture medium to achieve test concentrations, typically including multiples of the MIC (e.g., 0.5×, 1×, 2×, 4×, 8×MIC).

Experimental Setup: Combine equal volumes of standardized inoculum and antibiotic solutions in sterile tubes. Include growth control tubes (inoculum without antibiotic) and sterility control tubes (media only).

Incubation and Sampling: Inculate all tubes at the appropriate temperature. Remove samples (e.g., 1 mL) from each tube at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 hours).

Viable Count Determination: Serially dilute each sample in neutralizing broth to stop antimicrobial action. Plate appropriate dilutions onto agar plates in duplicate. Incubate plates for 18-24 hours, then enumerate colonies.

Data Analysis: Calculate CFU/mL at each time point and plot log₁₀ CFU/mL versus time to generate time-kill curves.

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Bactericidal Activity: Defined as a ≥3 log₁₀ decrease (99.9% reduction) in CFU/mL compared to the initial inoculum [2] [3].

Bacteriostatic Activity: Defined as maintenance of the initial inoculum level or a <3 log₁₀ decrease in CFU/mL [2].

Synergy Evaluation: For combination studies, synergy is typically defined as a ≥2 log₁₀ decrease in CFU/mL with the combination compared to the most active single agent [19].

The time-kill curves generated from this protocol provide visual representation of the rate and extent of antimicrobial activity, enabling classification of antibiotics based on their killing patterns and facilitating comparisons between different agents or regimens.

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Features of Static MIC and Time-Kill Kinetics Assays

| Feature | Static MIC Determination | Time-Kill Kinetics |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Resolution | Single endpoint (16-20 hours) | Multiple time points (0-24 hours) |

| Killing Dynamics | Not determined | Quantifies rate and extent of killing |

| Classification Ability | Limited bactericidal/bacteriostatic distinction | Clear bactericidal (≥3 log₁₀ kill) vs. bacteriostatic differentiation [2] [3] |

| Pattern Recognition | No time- or concentration-dependent pattern identification | Identifies concentration-dependent vs. time-dependent killing [20] [18] |

| Resistance Detection | Limited to homogeneous resistance | Can detect heteroresistance and evaluate resistance suppression [19] |

| Combination Therapy Assessment | Limited to fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) | Comprehensive synergy/additivity/antagonism evaluation [19] |

| PK/PD Modeling Utility | Limited to time above MIC (T>MIC) calculations | Enables development of sophisticated PK/PD models [18] [21] |

Table 2: Key Pharmacodynamic Parameters Obtainable from Time-Kill Kinetics

| Parameter | Description | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Maximal Kill Rate (Emax) | Maximum rate of bacterial killing achieved at high antibiotic concentrations [18] | Predicts efficiency of bacterial eradication at optimal concentrations |

| EC₅₀ | Antibiotic concentration producing 50% of maximal kill rate [18] | Indicates potency relative to killing efficiency |

| Hill Coefficient | Steepness of the concentration-effect relationship [18] | Predicts responsiveness to dose increases; higher values indicate steeper concentration-effect relationships |

| Bactericidal Threshold | Concentration required for ≥3 log₁₀ reduction in CFU/mL [2] | Guides target concentration for bactericidal efficacy |

| Post-Antibiotic Effect (PAE) | Persistent suppression of bacterial growth after antibiotic removal [19] | Informs dosing interval optimization |

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Time-Kill Kinetics Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Time-Kill Kinetics

| Item | Function/Purpose | Specifications/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | Supports bacterial growth during experiment | Mueller-Hinton Broth (MHB) for most organisms; supplemented media for fastidious organisms [17] |

| Neutralizing Solution | Stops antimicrobial action during sampling | Dey-Engley neutralizing broth; specific neutralizers for different antimicrobial classes [3] |

| Reference Antibiotics | Positive controls for antimicrobial activity | Certified reference standards of known potency [5] |

| Quality Control Strains | Verifies experimental conditions | ATCC strains (e.g., E. coli ATCC 25922, S. aureus ATCC 29213) [17] |

| Sterile Saline | Diluent for bacterial suspensions | 0.9% sodium chloride, isotonic solution [3] |

| Agar Plates | Colony counting and viability assessment | Mueller-Hinton Agar; blood agar for fastidious organisms [2] |

The implementation of time-kill kinetics assays represents a significant advancement over static MIC determinations, providing critical insights into the dynamic interactions between antimicrobial agents and bacterial pathogens. By capturing both time- and concentration-dependent effects, this methodology enables more accurate predictions of in vivo efficacy and supports the optimization of dosing regimens for improved clinical outcomes.

The relentless rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a formidable global challenge, rendering a growing number of infectious diseases difficult to treat and increasing mortality rates [22] [23] [24]. In the urgent quest for new anti-infective agents, time-kill kinetics assays have emerged as a vital tool for the sophisticated evaluation of novel compounds. This method provides dynamic, time-dependent data on the interaction between antimicrobial agents and microbial strains, offering insights far beyond those available from standard static minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) tests [22] [2] [25]. Within drug development pipelines, time-kill kinetics are indispensable for characterizing the rate and extent of microbial killing, determining whether a novel agent is bacteriostatic/fungistatic or bactericidal/fungicidal, and providing essential data for pharmacodynamic modeling to optimize dosing strategies [2] [26] [25]. These applications make the assay particularly valuable for evaluating candidates from diverse sources—including natural products like plumbagin from Plumbago zeylanica, mushroom extracts, and synthetic compounds—against priority pathogens [22] [5] [25].

Core Principles and Definitions

The time-kill kinetics assay measures the rate at which a microorganism is killed by a test product by tracking the number of surviving bacteria or fungi over a specified time period [2] [3]. The fundamental measure in these assays is the log10 reduction in colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter relative to the initial inoculum [3].

A key distinction in these assays is the classification of antimicrobial activity:

- Bactericidal/Fungicidal Activity: Defined as a greater than 3 log10 decrease in CFU/mL, equating to 99.9% killing of the initial inoculum [2].

- Bacteriostatic/Fungistatic Activity: The agent inhibits growth but does not achieve the 3 log10 reduction threshold, with the CFU count over time remaining roughly similar to the starting concentration [2] [26].

The assay can monitor the effect of various antimicrobial concentrations over time in relation to the different growth phases of microorganisms (lag, exponential, and stationary phases), providing a comprehensive profile of antimicrobial action [2].

Critical Applications in Drug Development

Profiling Novel Antimicrobial Compounds

Time-kill kinetics are crucial for the initial characterization of novel antimicrobial entities. For instance, research on plumbagin isolated from Plumbago zeylanica roots demonstrated its bacteriostatic and fungistatic activity against a panel of test organisms through time-kill studies, providing essential information for its development as a lead compound [22]. Similarly, studies on methanol extracts of Ghanaian mushrooms, including Trametes gibbosa and Schizophyllum commune, used time-kill kinetics to confirm their bacteriostatic action, supporting their potential as sources of new antimicrobial agents [26] [5].

Resistance Modulation and Combination Therapy

With multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens on the rise, combination therapy has become a promising strategy to extend antimicrobial lifespan and combat resistance [27] [24]. Time-kill kinetics serve as a gold standard method for evaluating in vitro synergy between drug candidates and existing antibiotics [27]. In resistance modulation studies, plumbagin at a subinhibitory concentration (4 μg/mL) was found to potentiate the activity of ketoconazole against Candida albicans by up to 12-fold, as revealed through follow-up kill-kinetic analyses [22]. Research on crude alkaloids from Phyllanthus fraternus also employed time-kill kinetics to demonstrate their bactericidal effects against specific pathogens and their potential to enhance the effectiveness of tetracycline [24].

Pharmacodynamic Modeling for Dosing Optimization

Time-kill curve data are frequently used in pharmacodynamic modeling to establish relationships between antimicrobial concentration and microbial killing rates [25]. These models help predict optimal dosing regimens for clinical applications. For example, a study on Neisseria gonorrhoeae used a pharmacodynamic model to analyze time-kill curves, generating parameters such as the maximal bacterial growth rate (ψmax), minimal growth rate (ψmin), Hill coefficient (к), and pharmacodynamic MIC (zMIC). This approach revealed gradual decreases in bactericidal effects across different antibiotics and identified purely bacteriostatic agents, providing critical information for improving future dosing strategies to treat gonorrhea [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents and Materials for Time-Kill Kinetics Assay

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | Supports microbial growth during assay | Mueller-Hinton Broth (MHB) [24], Graver-Wade (GW) medium for fastidious organisms [25], Nutrient broth [22] |

| Standard Antibiotics | Reference controls for comparison | Ciprofloxacin, ketoconazole, tetracycline, ceftriaxone [22] [24] [25] |

| Test Compounds | Investigational antimicrobial agents | Natural extracts (plumbagin, mushroom alkaloids) or synthetic compounds [22] [5] [24] |

| Saline Solution (0.9%) | Diluent for microbial suspension preparation | Used as a suspension medium for challenge organisms [3] |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Solvent for poorly water-soluble compounds | Used to dissolve compounds like plumbagin before dilution in culture medium [22] |

| Neutralizing Buffer | Halts antimicrobial action at sampling time points | Validated neutralizing fluid to stop antimicrobial activity for accurate plating [3] |

| Solid Agar Media | Enumeration of surviving microorganisms | Muller Hinton Agar (MHA), GCBA plates, Sabouraud dextrose agar [23] [25] |

Step-by-Step Methodology

The following workflow outlines the core procedures for conducting a time-kill kinetics assay, from sample preparation through data analysis:

Sample Preparation and Inoculum Standardization

Begin by preparing a standardized microbial inoculum from fresh overnight cultures. Adjust the suspension in saline or appropriate medium to match a 0.5 McFarland standard, typically resulting in approximately 1-5 × 108 CFU/mL. Further dilute this suspension in the chosen assay medium (e.g., Mueller-Hinton Broth or chemically defined GW medium for fastidious organisms) to achieve a final working concentration of approximately 106 CFU/mL [22] [25]. For pre-incubation, transfer the diluted bacteria to microtiter plates and incubate for approximately 4 hours with shaking (e.g., 150 rpm) at 35-37°C to synchronize the culture in the early- to mid-logarithmic growth phase before antimicrobial exposure [25].

Antimicrobial Preparation and Exposure

Prepare serial dilutions of the test and reference antimicrobial compounds in the appropriate solvent, typically covering a concentration range from below to above the MIC (e.g., 0.016× to 16× MIC) [25]. Add the antimicrobial solutions to the pre-incubated bacterial cultures. Include appropriate controls: a growth control (bacteria without antimicrobial), a vehicle control (bacteria with solvent alone), and a negative control (sterile medium only) [22] [2]. Maintain the assay system under optimal growth conditions throughout the exposure period.

Sampling, Viable Count Determination, and Data Analysis

Sample the cultures at predetermined time intervals (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 hours). At each time point, remove aliquots and immediately dilute in a validated neutralizing solution to stop antimicrobial action [3]. Perform serial 1:10 dilutions in sterile phosphate-buffered saline or appropriate diluent. Plate aliquots from appropriate dilutions onto solid agar media using spread-plating or pour-plating techniques. Incubate plates for 18-24 hours at optimal growth conditions, then enumerate the colonies to determine CFU/mL at each time point [3] [25].

Calculate the log10 CFU/mL for each sample and plot these values against time to generate time-kill curves. Compare the reduction in viable counts against the initial inoculum and the growth control to determine the killing kinetics. A ≥3 log10 decrease in CFU/mL compared to the initial inoculum indicates bactericidal activity, while lesser reductions that maintain or slow growth suggest bacteriostatic activity [2].

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Quantitative Analysis of Time-Kill Kinetics

Table 2: Key Parameters for Interpretation of Time-Kill Kinetics Data

| Parameter | Description | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Log10 Reduction | Decrease in viable count from initial inoculum | ≥3 log10 (99.9% killing): Bactericidal [2]<3 log10: Bacteriostatic [26] |

| Killing Rate | Slope of the kill curve | Steep slope: Rapid killingGradual slope: Slow killing |

| Post-Antibiotic Effect | Continued suppression after removal | Prolonged suppression: Persistent effectRapid regrowth: Limited persistent effect |

| Concentration Dependency | Effect of increasing antimicrobial concentrations | Increased killing with higher concentrations: Concentration-dependent killingSimilar killing despite concentration: Time-dependent killing |

| Regrowth | Increase in CFU after initial decline | Suggests potential resistance development or incomplete killing |

Pharmacodynamic Modeling

For advanced analysis, time-kill data can be fitted to pharmacodynamic models. The model described by Regoes et al. uses four key parameters to characterize antimicrobial action: the maximal growth rate without antimicrobial (ψmax), the minimal growth rate at high concentrations (ψmin), the Hill coefficient (κ) indicating steepness of the concentration-effect relationship, and the pharmacodynamic MIC (zMIC) representing the concentration where the growth rate is half of ψmax [25]. This modeling approach allows for quantitative comparison between different antimicrobial agents and supports optimized dosing regimen design.

Comparison with Other Antimicrobial Susceptibility Methods

Table 3: Comparison of Time-Kill Kinetics with Other Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Kill Kinetics | Time-dependent measurement of microbial killing in liquid medium | Provides dynamic killing profileDistinguishes bactericidal vs. bacteriostaticGold standard for synergy studies [27] | Time-consuming and labor-intensive [27]Requires significant technical expertise [27] |

| Broth Microdilution | Determination of MIC in liquid medium using dilution series | Quantitative resultsStandardized and reproducibleSuitable for multiple isolates | Static endpoint (single time point)Does not distinguish cidal vs. static [28] |

| Disk Diffusion | Measurement of inhibition zones around antibiotic disks on agar | Simple and inexpensiveWell-standardizedSuitable for routine testing | Qualitative/semi-quantitativeNot suitable for slow-growing organisms [23] |

| Agar Gradient Diffusion (Etest) | MIC determination using predefined antibiotic gradient on strips | Flexible for single drugsQuantitative MICsEasy to perform | Expensive for routine useLimited to available gradients [28] |

Time-kill kinetics assays represent a powerful, information-rich methodology that provides critical insights into the dynamics of antimicrobial action essential for drug development. The ability to distinguish between bactericidal and bacteriostatic activity, evaluate synergistic combinations for overcoming resistance, and generate data for pharmacodynamic modeling makes this approach invaluable for advancing novel antimicrobial candidates from discovery through preclinical development. While the method demands specialized expertise and resources, its comprehensive output justifies its application in characterizing promising therapeutic agents, particularly as we face the escalating threat of antimicrobial resistance worldwide.

Executing the Assay: A Step-by-Step Protocol from Inoculum to Analysis

Time-kill kinetics assays represent a cornerstone methodology in antimicrobial research, providing a dynamic and quantitative assessment of an antimicrobial agent's bactericidal or bacteriostatic activity over time. Unlike endpoint determinations such as the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), time-kill kinetics reveal the rate and extent of microbial killing, offering critical insights into the pharmacodynamics of antimicrobial agents [2]. This methodology is particularly valuable for characterizing novel antimicrobial compounds, studying combination therapies, and evaluating agents for treatment of serious infections where rapid bactericidal activity is essential [29].

Two principal standardized guidelines govern the execution of time-kill kinetics assays: the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M26 document, "Methods for Determining Bactericidal Activity of Antimicrobial Agents," and the ASTM International E2315, "Standard Guide for Assessment of Antimicrobial Activity Using a Time-Kill Procedure" [29] [30]. These protocols, while sharing a common objective, are optimized for different applications within antimicrobial research and development. CLSI M26 is primarily oriented toward clinical correlation and predicting bacterial eradication in patients, especially in scenarios involving compromised host immune defenses [29]. In contrast, ASTM E2315 is widely applied in the industrial sector for disinfectant product development, providing a rapid and reproducible means to measure the biocidal potential of liquid antimicrobial formulations [31].

Table 1: Core Applications and Characteristics of CLSI M26 and ASTM E2315

| Feature | CLSI M26 | ASTM E2315 |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Clinical therapeutic development; predicting in vivo efficacy [29] | Disinfectant and antiseptic product development [2] [31] |

| Typical Test Duration | Up to 24 hours [2] | Shorter contact times (seconds to minutes) or up to 24 hours [2] |

| Defining Bactericidal Activity | ≥3 log10 (99.9%) reduction in CFU/mL [2] | Percentage killed over time [31] |

| Testing Model | Predictive model for systemic treatment | "Best-case" suspension model for liquid contact [31] |

| Key Outcome | Bactericidal vs. bacteriostatic classification [2] | Death curve (kill-rate) for biocidal potential [31] |

Theoretical Foundations of Time-Kill Kinetics

Principles of Bactericidal Activity

The fundamental principle underlying time-kill kinetics is the direct quantification of viable microorganisms after exposure to an antimicrobial agent at specified time intervals. The assay monitors the effect of various antimicrobial concentrations throughout the different growth phases of bacteria (lag, exponential, and stationary phase), providing a time-course profile of microbial survival [2]. Bactericidal activity is stringently defined as a ≥3 log10-fold decrease in colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter, which corresponds to a 99.9% killing of the initial inoculum [2]. An agent that inhibits growth but does not achieve this level of killing is classified as bacteriostatic.

The post-antibiotic effect and the inhibitory effects of sub-MIC antibiotic concentrations are other critical factors that influence the microbiologic response of patients and can be informed by time-kill studies [29]. It is crucial to recognize that clinical cure depends largely upon host factors, and while bactericidal tests provide a rough prediction of bacterial eradication, they are one component of a comprehensive efficacy assessment [29].

Signaling Pathways and Antimicrobial Mechanisms

Antimicrobial agents exert their effects through diverse mechanisms of action, many of which involve targeting specific bacterial pathways. The following diagram illustrates the primary cellular targets and the consequential lethal pathways activated in bacterial cells upon antimicrobial exposure.

CLSI M26 Protocol: Detailed Workflow

Experimental Design and Preparation

The CLSI M26 guideline provides a standardized framework for assessing the bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents, with a focus on ensuring accurate and reproducible testing that can predict bacterial eradication in clinical settings [29]. The protocol is intended primarily for testing aerobic bacteria that grow in adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth, which may be supplemented with human serum or its ultrafiltrate to simulate certain in vivo conditions [29].

Key preparatory steps include:

- Organism Selection and Inoculum Preparation: Select well-isolated colonies (3-5) from a fresh culture (18-24 hours) to prepare a bacterial suspension. The turbidity of this inoculum must be standardized to a 0.5 McFarland standard, which corresponds to approximately 1-2 x 10^8 CFU/mL [32].

- Antimicrobial Agent Preparation: Prepare serial dilutions of the antimicrobial agent in the chosen broth medium. Testing typically includes concentrations at, above, and below the MIC, as well as a growth control without antimicrobial agent.

- Quality Control Strains: Include appropriate quality control strains to ensure testing conditions, media, and reagents are performing within acceptable limits [32].

Step-by-Step Procedural Workflow

The following diagram outlines the critical stages in the CLSI M26 time-kill kinetics assay, from initial preparation to final data interpretation.

Detailed Protocol:

- Inoculum Standardization: Prepare a bacterial suspension directly from colonies and adjust to a 0.5 McFarland standard [32]. Confirm the initial viable count by serial dilution and plating.

- Reaction Mixture Setup: Combine equal volumes of the standardized inoculum and antimicrobial solution in sterile tubes, resulting in a final bacterial density of approximately 5 x 10^7 CFU/mL. Include a growth control (inoculum + broth without antimicrobial).

- Incubation and Sampling: Incubate the test tubes at 35°C under ambient atmosphere. At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 4, 8, and 24 hours), remove aliquots from each tube [2].

- Viable Count Determination: Perform serial 10-fold dilutions of each aliquot in a neutralizing solution to stop antimicrobial action. Plate appropriate dilutions onto agar media and incubate for 18-24 hours. Count the resulting colonies and calculate the CFU/mL for each sample and time point.

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: Plot the log10 CFU/mL against time for each antimicrobial concentration and the growth control. A decrease of ≥3 log10 CFU/mL compared to the initial inoculum defines bactericidal activity. A <3 log10 reduction with suppression of growth relative to the control indicates bacteriostatic activity [2].

ASTM E2315 Protocol: Detailed Workflow

Experimental Design and Preparation

The ASTM E2315 standard guide is designed as a flexible framework for measuring the reduction of a microbial population in a liquid suspension after exposure to a test material over time [30]. This method is particularly valuable for disinfectant product developers as a fast, relatively inexpensive, and reproducible way to measure biocidal potential [31].

Key preparatory steps include:

- Test Microorganism Preparation: Prepare microbial cultures as specified. For most bacteria, a 24-hour culture in nutrient broth is suitable. For fungi, a spore preparation from a saline wash is typically used [31].

- Test Substance and Controls: Place equal volumes of the liquid test product in sufficient sterile test vessels. Include a saline control vessel spiked with the same microbial culture to measure initial microbial concentrations and appropriate neutralization controls.

- Contact Time Determination: Pre-determine contact times based on the expected use of the antimicrobial product. These can range from very brief intervals (seconds/minutes) for disinfectants to longer periods (hours) [2] [31].

Step-by-Step Procedural Workflow

The ASTM E2315 procedure focuses on direct interaction between microorganisms and antimicrobials in a liquid suspension, modeling scenarios like disinfectant rinses.

Detailed Protocol:

- Culture Preparation: Grow the test microorganisms under optimal conditions to achieve a high cell density. Adjust the concentration if necessary.

- Test Inoculation: Add a volume of microbial culture (typically 1/10 of the product volume) to the test vessel containing the antimicrobial product and mix immediately. This step marks time zero [31].

- Sampling and Neutralization: After predetermined contact times, remove small aliquots from the mixture and transfer them to a solution containing an appropriate neutralizer to stop the antimicrobial action effectively.

- Viable Count Determination: Perform serial dilutions of the neutralized samples and plate onto appropriate agar media. Incubate plates and count the resulting colonies to determine the surviving CFU/mL at each time point.

- Data Analysis: Plot the number of surviving microorganisms (log10 CFU/mL) against time to generate a "death curve." Calculate the percentage reduction in viability at each time point compared to the initial concentration determined from the saline control [31].

Comparative Analysis and Data Interpretation

Key Differences and Applications

While both CLSI M26 and ASTM E2315 assess antimicrobial activity over time, their design philosophies reflect their distinct applications. CLSI M26 establishes uniform test procedures to permit comparison of different datasets with a focus on clinical correlation, especially for situations like endocarditis where bactericidal activity is crucial [29]. The methodology is evolving and requires more work on methodological aspects and clinical correlations [29]. In contrast, ASTM E2315 offers a more flexible framework that is particularly suited for industrial product development, providing a "best-case" scenario for evaluating liquid antimicrobial formulations [31].

A critical methodological difference lies in the neutralization step. ASTM E2315 explicitly requires immediate neutralization of the antimicrobial agent upon sampling to precisely define the contact time [31]. While CLSI M26 also implies this step, its emphasis is on the standardized growth conditions and the definition of bactericidal activity. Furthermore, the growth medium in CLSI M26 is specifically defined as adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth, potentially supplemented with human serum, to better simulate certain in vivo conditions [29].

Table 2: Direct Comparison of CLSI M26 and ASTM E2315 Methodologies

| Parameter | CLSI M26 | ASTM E2315 |

|---|---|---|

| Inoculum Standardization | 0.5 McFarland Standard [32] | Broth culture or spore suspension [31] |

| Typical Inoculum Size | ~5 x 10^7 CFU/mL (final) | High concentration (volume: 1/10 of product) [31] |

| Growth Medium | Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (± human serum) [29] | Not specified (liquid test substance as environment) [31] |

| Incubation Atmosphere | Ambient air [32] | Not specified (dependent on test system) |

| Sampling Time Points | e.g., 0, 4, 8, 24 hours [2] | Pre-determined contact times (flexible) [30] |

| Neutralization | Implied for accurate counts | Explicitly required post-sampling [31] |

| Key Data Output | Log10 CFU/mL reduction over time [2] | Percentage killed over time; Death curve [31] |

Data Interpretation and Quality Control

Robust data interpretation and quality assurance are fundamental to both protocols. For CLSI M26, the primary endpoint is the classification of an agent as bactericidal (≥3 log10 reduction), bacteriostatic, or inactive based on the reduction from the initial inoculum [2]. The growth control must show adequate growth to validate the test conditions.

In ASTM E2315, results are often presented as kill curves showing the rate of microbial death, and the percentage reduction is calculated for each contact time. The method's strength is its ability to study the impact of a disinfectant on microorganisms over time with relative ease and under controlled parameters [31].

For both standards, implementation of a robust quality assurance program is critical. This includes using quality control strains to verify testing conditions, ensuring staff competency, and participating in proficiency testing programs to maintain accuracy and consistency [32]. Furthermore, all materials and reagents must be of verified quality to ensure reliable and reproducible results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of time-kill kinetics assays requires carefully selected and quality-controlled materials. The following table details the essential components of the researcher's toolkit for these studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Time-Kill Kinetics Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function & Purpose | Specification & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth | Standard growth medium for CLSI M26; ensures reproducible ion concentration and pH [29]. | Must be formulated according to CLSI specifications; may be supplemented with human serum or ultrafiltrate [29]. |

| Quality Control Strains | Verifies performance of test systems, media, and reagents [32]. | Strains with established zone/MIC ranges (e.g., S. aureus ATCC 29213); used for periodic QC testing. |

| McFarland Standards | Turbidity standard for inoculum preparation and standardization [32]. | 0.5 McFarland standard (~1.5 x 10^8 CFU/mL) is typically used for broth inoculation. |

| Neutralizing Solution | Inactivates antimicrobial agent at specific time points to stop killing action [31]. | Critical for accurate contact times in ASTM E2315; composition depends on test agent (e.g., polysorbate, lecithin, thiosulfate). |

| Agar Media for Enumeration | Supports growth of survivors for viable counting via colony formation. | Non-selective media like Tryptic Soy Agar; must be validated for recovery of test organisms. |

| Antimicrobial Reference Powders | Provides known active agents for comparison and control. | High-purity, potency-certified materials for preparing stock solutions and serial dilutions. |