Resistance-Proofing Therapies: Novel Strategies to Prevent Antibiotic Resistance Development During Treatment

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of innovative strategies designed to counteract the development of antibiotic resistance during therapeutic interventions.

Resistance-Proofing Therapies: Novel Strategies to Prevent Antibiotic Resistance Development During Treatment

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of innovative strategies designed to counteract the development of antibiotic resistance during therapeutic interventions. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes the latest scientific advances, from foundational resistance mechanisms to cutting-edge clinical applications. The review covers the molecular drivers of resistance, explores emerging 'resistance-resistant' therapeutic modalities such as evolutionary steering and combination therapies, and addresses the significant translational challenges in the current antibiotic development pipeline. Furthermore, it evaluates validation frameworks and comparative effectiveness of these novel approaches, offering a critical perspective on future directions for preserving antibiotic efficacy in an era of escalating antimicrobial resistance.

Understanding the Enemy: Foundational Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance Emergence

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a critical global health threat, undermining the effectiveness of life-saving treatments and placing populations at heightened risk from common infections and routine medical interventions [1]. According to the World Health Organization's (WHO) 2025 Global Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Report (GLASS), which draws on data from more than 23 million laboratory-confirmed infections across 110 countries, the situation is escalating rapidly [1]. The data reveals that one in six bacterial infections worldwide is now resistant to antibiotic treatments [2]. Between 2018 and 2023, antibiotic resistance increased in over 40% of the pathogen-antibiotic combinations monitored by the WHO, with an average annual rise of 5–15% [2]. This technical brief outlines the scope of the crisis and provides actionable guidance for researchers developing new therapeutic strategies.

Quantifying the Global Burden: Key Surveillance Data

The following tables summarize the core quantitative findings from the latest WHO surveillance, providing a snapshot of resistance levels for critical pathogen-antibiotic combinations.

Table 1: Global Resistance Prevalence for Key Pathogen-Antibiotic Combinations (2023)

| Pathogen | Antibiotic Class | Global Resistance Prevalence | Key Regional Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Third-generation cephalosporins | >40% [2] | Exceeds 70% in the African Region [2] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Third-generation cephalosporins | >55% [2] | Exceeds 70% in the African Region [2] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Carbapenems | Increasing, narrowing treatment options [2] | Becoming more frequent globally [2] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Methicillin (MRSA) | ~27% (widespread) [3] | |

| All bacterial pathogens | All treatments | 1 in 6 infections (global average) [2] | 1 in 3 in SE Asia & Eastern Mediterranean; 1 in 5 in African Region [2] [4] |

Table 2: Surveillance Capacity and Its Impact (2023) [2] [3] [4]

| Surveillance Metric | Status | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Country participation in GLASS | 104 reporting countries (4x increase since 2016) [3] | Improved but incomplete global picture |

| Non-reporting countries | 48% of countries did not report data [2] | Critical data gaps persist, especially in underserved areas |

| Data quality | ~50% of reporting countries lack systems for reliable data [2] | Resistance may be over- or underestimated in some regions |

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides for AMR Research

FAQ 1: Which bacterial pathogens currently pose the most urgent threat for therapeutic research?

Answer: Based on WHO 2025 data, drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria represent the most dangerous and escalating threat [2]. The highest priority pathogens include:

- E. coli and K. pneumoniae: These are leading causes of drug-resistant bloodstream infections, with resistance to first-line treatments (third-generation cephalosporins) exceeding 40% and 55%, respectively, globally [2]. Resistance to last-resort carbapenems is also rising [2].

- Acinetobacter spp.: Noted for increasing resistance to essential antibiotics like carbapenems and fluoroquinolones, severely limiting treatment options [2].

- Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): Methicillin resistance remains widespread at approximately 27%, sustaining its status as a major priority for research [3].

FAQ 2: My research on a novel compound is based on older resistance data. How can I ensure my experimental design reflects current real-world resistance patterns?

Troubleshooting Guide: A disconnect between historical data and current resistance trends is a common pitfall that can invalidate a compound's perceived efficacy.

- Problem: Novel compound shows high efficacy in vitro against lab-evolved resistant strains, but fails against contemporary clinical isolates.

- Solution:

- Source Recent Clinical Isolates: Actively collaborate with clinical microbiology laboratories in diverse geographical locations to obtain recent, clinically relevant isolates. The WHO report highlights significant regional variations (e.g., >70% resistance for E. coli in Africa vs. global average of >40%) [2]. Your test panel should reflect this diversity.

- Consult Real-Time Surveillance Data: Utilize the WHO GLASS dashboard and other national AMR surveillance databases to inform the selection of antibiotic comparators in your assays. Ensure you test against antibiotics known to have high failure rates in the region you are modeling.

- Validate with Genotypic Analysis: Use Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) on your clinical isolates to confirm the presence of contemporary, clinically relevant resistance mechanisms (e.g., ESBL, carbapenemase genes) [5] [6]. This moves beyond phenotypic results alone and provides mechanistic insight.

FAQ 3: What are the best practices for incorporating rapid diagnostics into my therapeutic efficacy study protocols?

Troubleshooting Guide: Integrating rapid diagnostics can significantly reduce the Turnaround Time (TAT), a critical factor in combating AMR.

- Problem: Reliance on conventional culture-based AST (taking 48-72 hours) delays critical data in animal models or in vitro systems, slowing down the research pipeline.

- Solution: Implement a tiered diagnostic strategy.

- For Rapid Pathogen ID & Resistance Screening: Use MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry for rapid pathogen identification and FTIR Spectroscopy for preliminary typing and resistance detection [5]. These can provide data within hours.

- For Comprehensive Resistance Gene Profiling: Employ Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). Techniques like Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) or targeted Hybrid Capture panels can detect known and novel resistance genes from a sample without the need for prior cultivation, offering a complete resistome profile [5] [6].

- For Phenotypic Confirmation: Use automated broth microdilution systems (e.g., VITEK 2, Sensititre) or gradient diffusion tests (e.g., E-test) for gold-standard Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) determination, but with the prior knowledge gained from rapid methods to focus your testing [5].

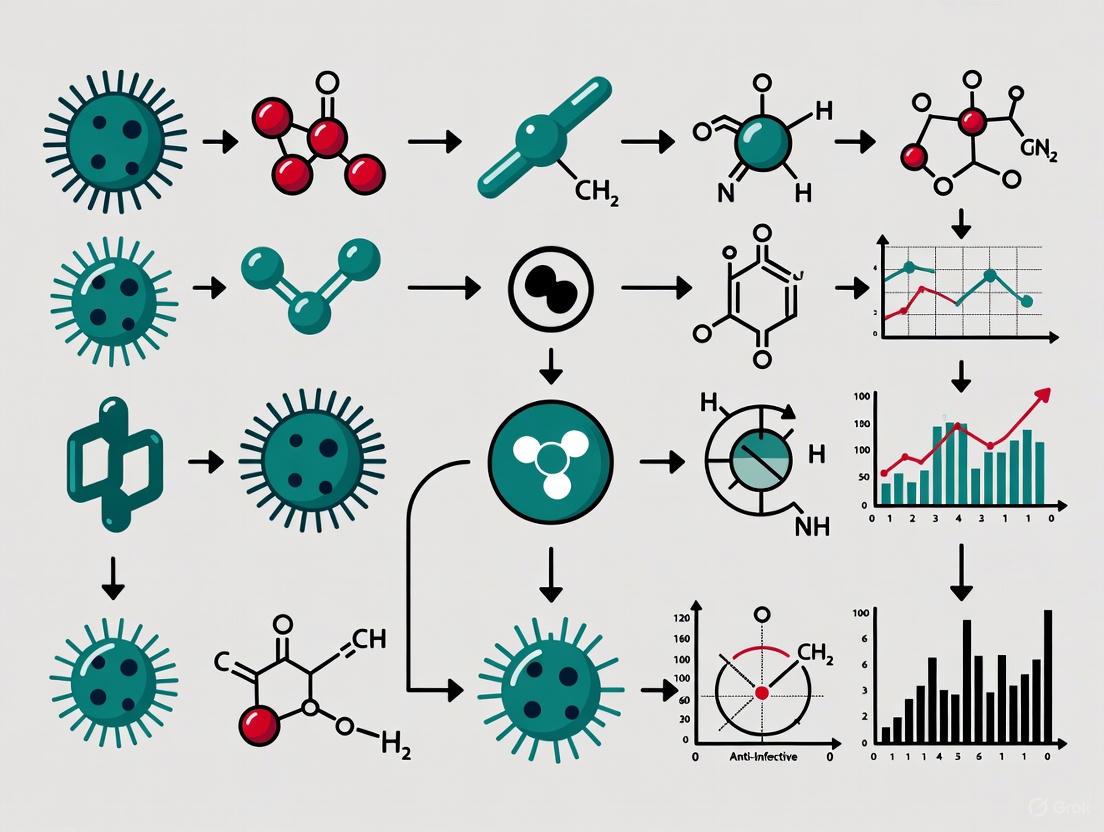

Diagram: Integrated Workflow for Rapid AMR Diagnostics in Research. This workflow combines rapid identification and genotypic methods with phenotypic confirmation to provide a comprehensive AMR profile faster than conventional methods alone [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Methods for AMR Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AMR Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in AMR Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sensititre Broth Microdilution Panels | Gold-standard for determining Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) [5]. | Quantifying resistance levels of clinical isolates against a novel compound panel. |

| Whole Genome Sequencing Kits (e.g., Illumina DNA Prep) | Comprehensive genomic analysis to identify known and novel resistance mechanisms [6]. | Characterizing the resistome of a bacterial pathogen and detecting horizontal gene transfer events. |

| Targeted AMR Panels (e.g., AmpliSeq for Illumina AMR Panel) | Focused sequencing of 478+ AMR genes for efficient screening [6]. | Rapidly screening a large collection of isolates for a wide array of known resistance determinants. |

| MALDI-TOF MS Reagents | Ultra-rapid microbial identification to species level [5]. | Confirming pathogen identity in animal infection models prior to efficacy testing. |

| Urinary/Respiratory Pathogen ID/AMR Panels | Multiplexed detection of pathogens and resistance markers from complex samples [6]. | Studying polymicrobial infections and their impact on resistance emergence in vivo. |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Using Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) for Resistome Analysis

Methodology: This protocol outlines the steps for using WGS to comprehensively identify antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) in bacterial isolates [5] [6].

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Use a validated kit (e.g., Illumina DNA Prep) to extract high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from a pure bacterial culture. Quantify DNA using fluorometry.

- Library Preparation: Fragment the gDNA and attach sequencing adapters compatible with your NGS platform. For large-scale studies, incorporate unique dual indices (UDIs) to multiplex multiple samples in a single sequencing run.

- Sequencing: Perform sequencing on an Illumina platform (e.g., MiSeq, NextSeq) to achieve sufficient coverage (e.g., 50x-100x) for high-confidence variant calling and gene detection.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Use tools like FastQC to assess raw read quality. Trim adapters and low-quality bases with Trimmomatic.

- Assembly: De novo assemble quality-filtered reads into contigs using assemblers like SPAdes.

- Resistance Gene Identification: Annotate the assembled genome by querying contigs against curated ARG databases (e.g., CARD, ResFinder) using BLAST or dedicated analysis pipelines (e.g., ARIBA).

Protocol 2: Implementing a High-Throughput qPCR Screen for ARGs

Methodology: This protocol describes a high-throughput method to screen a large number of bacterial isolates or environmental DNA extracts for a predefined set of ARGs [5].

- DNA Template Preparation: IsDNA from single bacterial colonies or directly from complex samples (e.g., stool, wastewater). Normalize all DNA concentrations to a standard value (e.g., 10 ng/μL).

- Primer/Probe Design: Select primers and TaqMan probes targeting a comprehensive panel of ARGs (e.g., blaKPC, mecA, vanA). Ensure probes are labeled with different fluorophores for multiplexing.

- qPCR Setup: Use a 384-well plate format. Each reaction should contain: 1X master mix, forward and reverse primers, TaqMan probe, template DNA, and nuclease-free water. Include no-template controls (NTCs) and positive controls (plasmids containing target ARG) on each plate.

- Amplification and Detection: Run the plate on a high-throughput real-time PCR instrument. Use the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 10 min (polymerase activation), followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec (denaturation) and 60°C for 1 min (annealing/extension).

- Data Analysis: Determine cycle threshold (Ct) values. A sample is considered positive for an ARG if its Ct value is below a predetermined threshold (established using positive controls) and the amplification curve is sigmoidal.

Diagram: Implementation Research (IR) Continuum for AMR Interventions. Successfully moving an intervention from the lab to widespread use requires navigating a three-phase continuum, all while accounting for critical context domains that influence real-world adoption and impact [7].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My bacterial strains are showing resistance to multiple, structurally unrelated antibiotics. What is the most likely mechanism, and how can I confirm it? A1: This multi-drug resistance (MDR) pattern strongly suggests the overexpression of efflux pumps [8]. To confirm:

- Inhibitor Assays: Use a broad-spectrum efflux pump inhibitor (e.g., Phe-Arg β-naphthylamide, PAβN) in combination with your antibiotics. A significant decrease in the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of the antibiotics in the presence of the inhibitor confirms efflux pump activity [8].

- Genetic Analysis: Perform PCR or whole-genome sequencing to identify and quantify the expression of genes encoding known MDR pumps, such as those from the RND superfamily (e.g., AcrAB-TolC in E. coli or MexAB-OprM in P. aeruginosa) [8] [9].

Q2: My β-lactam antibiotics are failing against clinical isolates. How do I distinguish between enzymatic degradation and target site modification? A2: Both mechanisms can affect β-lactams, but they can be differentiated experimentally.

- For Enzymatic Degradation (e.g., by β-lactamases):

- Test: Use a β-lactamase inhibitor (e.g., clavulanic acid, sulbactam) in combination with the antibiotic. A restored antibiotic effect (synergy) indicates the presence of a susceptible β-lactamase (e.g., ESBLs) [9] [10].

- Molecular Detection: Perform specific PCR tests for prevalent resistance genes like blaNDM (metallo-β-lactamase) or blaKPC (serine carbapenemase) [9] [10].

- For Target Site Modification (e.g., PBP alteration):

- This is common in Gram-positives like MRSA (Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus).

- Test: Detect the mecA gene, which codes for an alternative penicillin-binding protein (PBP2a) with low affinity for β-lactams [11].

Q3: My research involves combating efflux-mediated resistance. What are the latest innovative approaches beyond traditional inhibitors? A3: Research is moving beyond simple inhibition to more sophisticated strategies:

- "Resistance Hacking": A proof-of-concept study on Mycobacterium abscessus used a structurally modified antibiotic (florfenicol) that is activated by a bacterial resistance protein (Eis2). This creates a perpetual cascade where the bacterium's own resistance mechanism amplifies the drug's effect, effectively turning resistance against itself [12].

- CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing: This technology can be used to precisely target and disrupt genes encoding efflux pumps, potentially reversing the resistant phenotype. Phage-delivered CRISPR systems are being explored for this purpose [8] [10].

Q4: According to recent surveillance data, which drug-pathogen combinations currently pose the most severe threat? A4: The WHO's 2025 report highlights critical threats, largely driven by the mechanisms discussed here [2] [13]:

- Gram-negative bacteria, particularly E. coli and K. pneumoniae, are the most concerning.

- Over 40% of E. coli and 55% of K. pneumoniae isolates are resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (a first-line treatment), often due to ESBL production (enzymatic degradation) [2].

- Carbapenem resistance, once rare, is becoming more frequent in these pathogens, largely due to the spread of carbapenemase enzymes (e.g., NDM, KPC), severely limiting treatment options [2] [10].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent results in efflux pump inhibition assays.

- Potential Cause: Degradation or instability of the efflux pump inhibitor in the growth medium.

- Solution: Prepare fresh inhibitor stock solutions for each experiment. Verify the stability profile of your specific inhibitor and ensure it is compatible with your assay conditions (e.g., pH, temperature) [8].

Problem: Failure to detect a known resistance gene via PCR in a phenotypically resistant strain.

- Potential Cause: The resistance may be due to a previously unidentified mutation or a novel resistance gene.

- Solution: Move beyond targeted PCR to whole-genome sequencing. This allows for the discovery of new resistance mutations (e.g., in promoter regions that upregulate efflux pumps) or novel horizontally acquired genes [8] [9].

Problem: Investigating a new compound, but unable to determine its primary resistance mechanism.

- Solution: Implement a systematic workflow:

- Check for Enzymatic Degradation: Incubate the compound with bacterial cell lysates and use HPLC/MS to look for degradation products.

- Check for Efflux: Perform the accumulation/efflux assay with a fluorescent substrate (see protocol below) in the presence of your compound.

- Check for Target Modification: Select for resistant mutants in vitro, then sequence the putative target gene(s) to identify mutations [8] [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Detecting β-Lactamase Activity via Nitrocefin Hydrolysis Assay

Principle: Nitrocefin is a chromogenic cephalosporin that changes color from yellow to red upon hydrolysis by β-lactamase enzymes. This is a quick, qualitative test for β-lactamase production [9].

Materials:

- Nitrocefin solution (0.5 mg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline or DMSO)

- Test bacterial culture (fresh, late-logarithmic phase)

- Sterile loop or swab

- Microfuge tubes or a microtiter plate

- 37°C incubator

Method:

- Suspend several bacterial colonies in 100 µL of PBS to create a dense suspension.

- Add 50 µL of the nitrocefin solution to the bacterial suspension.

- Incubate the mixture at 37°C and observe for color change within 5-15 minutes.

- Interpretation: A rapid color change to red indicates a positive result for β-lactamase production.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Efflux Pump Activity Using an Ethidium Bromide Accumulation Assay

Principle: Ethidium bromide (EtBr) is a fluorescent substrate for many broad-specificity efflux pumps. Inhibiting these pumps leads to increased intracellular EtBr accumulation and higher fluorescence [8].

Materials:

- Bacterial culture in mid-log phase

- Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) stock solution (1 mg/mL)

- Efflux pump inhibitor (e.g., PAβN, 25-100 µg/mL)

- HEPES or PBS buffer (pH 7.0)

- Spectrofluorometer or fluorescence microplate reader

- 37°C water bath or incubator

Method:

- Harvest bacterial cells by centrifugation, wash twice, and resuspend in buffer to an OD~600~ of ~0.5.

- Divide the cell suspension into two aliquots:

- Test: Pre-incubate with an efflux pump inhibitor for 10 minutes.

- Control: Pre-incubated with buffer only.

- Add EtBr to both tubes to a final concentration of 1-2 µg/mL.

- Immediately transfer the mixtures to a cuvette or microplate and measure fluorescence at excitation/emission wavelengths of ~530/600 nm every minute for 30-60 minutes.

- Interpretation: A steeper increase in fluorescence in the test sample compared to the control indicates that the inhibitor successfully blocked efflux activity, leading to EtBr accumulation.

Data Presentation: Global Resistance Prevalence

The table below summarizes key quantitative data from the WHO's 2025 Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Report, illustrating the severe and widespread nature of resistance driven by these core molecular mechanisms [2] [13].

Table 1: Global Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance in Key Bacterial Pathogens (WHO GLASS 2025 Report)

| Bacterial Pathogen | Antibiotic Class | Resistance Prevalence (%) | Primary Molecular Mechanism(s) | Key Geographic Concern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Third-generation cephalosporins | >55% globally (exceeds 70% in Africa) | Enzymatic degradation (ESBLs) | Worldwide, highest in SE Asia, E. Mediterranean, Africa [2] [13] |

| Escherichia coli | Third-generation cephalosporins | >40% globally | Enzymatic degradation (ESBLs) | Worldwide, high in SE Asia, E. Mediterranean, Africa [2] [13] |

| Acinetobacter spp. | Carbapenems | Increasing, specific rates vary | Enzymatic degradation (Carbapenemases), Efflux pumps | A major concern in healthcare settings worldwide [2] [10] |

| Various Gram-negative bacteria | Carbapenems | Rising | Enzymatic degradation (e.g., blaKPC, blaNDM, blaOXA-48) | Documented regional spread in Europe (e.g., Moldova, Ukraine) [10] |

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and their applications for studying the core molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms

| Research Reagent | Function / Target | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrocefin | Chromogenic β-lactamase substrate | Qualitative and kinetic assessment of β-lactamase enzyme activity [9] |

| Phe-Arg β-naphthylamide (PAβN) | Broad-spectrum efflux pump inhibitor | Used in combination assays to confirm efflux-mediated resistance and study pump kinetics [8] |

| Clavulanic Acid | β-lactamase inhibitor (primarily for ESBLs) | Used in combination disk tests or broth microdilution to confirm Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL) production [9] [10] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Genome editing tool | Precise knockout of resistance genes (e.g., efflux pump genes, beta-lactamase genes) to study function and reverse resistance [8] [10] |

| Specific PCR Primers (e.g., for blaKPC, blaNDM, mecA) | Molecular detection of resistance genes | Rapid genotypic identification and surveillance of specific resistance mechanisms in bacterial isolates [9] [10] |

Mechanism and Workflow Visualization

Efflux Pump Resistance and Inhibition

Resistance Mechanism Identification Workflow

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a escalating global health crisis, directly causing an estimated 1.27 million deaths annually and contributing to nearly 5 million more [14]. A core mechanism driving the evolution of resistance in bacteria is their innate capacity for rapid adaptation under pressure. This technical resource center focuses on two critical components of bacterial evolvability: stress-induced mutagenesis and the SOS response. These interconnected systems allow bacterial populations to increase their genetic diversity when faced with stressors like antibiotics, accelerating the development of resistance [15] [16]. Understanding and experimentally disrupting these pathways is essential for developing novel therapeutic strategies to curb the rise of resistant superbugs.

FAQs: Core Concepts for Researchers

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between the SOS response and stress-induced mutagenesis?

The SOS response is a specific, inducible DNA repair network activated by DNA damage. It is a defined regulon controlled by the LexA repressor and RecA inducer [17] [18]. In contrast, stress-induced mutagenesis is a broader phenomenon describing a transient increase in mutation rates under stress, which can be fueled by multiple mechanisms, including the SOS response [15]. The SOS response is a key driver of stress-induced mutagenesis, but other stress pathways, like the general stress response (RpoS) and the stringent response, also contribute [15] [19].

Q2: How does antibiotic treatment itself promote resistance via these mechanisms?

Many antibiotic classes directly or indirectly cause DNA damage. For example, ciprofloxacin (a fluoroquinolone) inhibits topoisomerases, leading to double-strand breaks [18]. This damage activates the SOS response. Subsequently, SOS-induced error-prone DNA polymerases (like Pol IV and Pol V) perform translesion synthesis, which is inherently mutagenic [17] [20]. This creates genetic diversity, including mutations that can confer antibiotic resistance, precisely when the bacterial population is under selection pressure from the drug [18] [19].

Q3: Why do we observe heterogeneous responses to DNA damage in clonal bacterial populations?

Recent single-cell studies using fluorescent SOS reporters (e.g., GFP under control of recA or umuDC promoters) have revealed that the SOS response oscillates in individual cells [18]. Instead of a simple on/off switch, cells exhibit one, two, or even three successive peaks of SOS gene expression after damage. This digital pulsating suggests that the SOS response is tuned to cope with a certain level of damage per pulse. The heterogeneity may arise from stochastic fluctuations in key limiting factors, such as RecA nucleoprotein filament dynamics or UmuD cleavage [18].

Q4: What is the connection between the SOS response, biofilms, and antimicrobial tolerance?

Biofilms are hotbeds for SOS induction. The dynamic biofilm environment generates endogenous DNA-damaging factors, such as reactive oxygen species and metabolic byproducts [19]. Furthermore, the SOS response plays a significant role in biofilm formation itself. Biofilms are highly recalcitrant to antimicrobials, sheltering persistent cells. The induction of the SOS response within this protected environment fuels bacterial adaptation and diversification, making biofilms a key reservoir for the emergence of resistance [19].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions in SOS and Mutagenesis Research

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low mutation frequency in stress assays. | Insufficient stressor dose/duration; repair pathways overwhelming mutagenesis. | - Titrate stressor (e.g., antibiotic concentration) to find sub-lethal but inducing levels [16].- Use mutants deficient in high-fidelity repair (e.g., uvrB). |

| High background mutation rate in controls. | Pre-existing mutator alleles (e.g., in mutS, mutL) in your strain. |

Resuscitate strains from single colonies and verify genotype; use whole-genome sequencing to check for mutator phenotypes. |

| No SOS induction detected via reporter. | Non-cleavable LexA repressor; defective RecA; insufficient DNA damage. | - Use a positive control (e.g., low-dose UV irradiation, mitomycin C) [18].- Verify genotype of recA and lexA genes. |

| Inconsistent results in persister cell assays. | Cell population heterogeneity; variations in culture growth phase. | - Ensure cultures are grown to the exact same optical density and phase (e.g., mid-log vs. stationary) [19].- Use high-resolution, single-cell reporter systems to capture heterogeneity [18]. |

Quantitative Data on Mutagenesis and Resistance

Table 2: Key Stress-Induced Mutagenesis Systems and Their Genetic Dependencies

| System Name | Organism | Mutation Type | Selected Phenotype | Key Genetic Requirements | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Mutation (Lac+) | E. coli | Frameshifts | Growth on lactose | Pol IV, RecA, RecBCD, RpoS, Ppk | [15] |

| ROSE Mutagenesis | E. coli | Base substitutions | Rifampicin resistance | CyaA, RecA, LexA*, Pol I | [15] |

| Mutagenesis in Aging Colonies (MAC) | E. coli | Base substitutions | Rifampicin resistance | RpoS, Pol II, MMR* | [15] |

| SOS-Dependent Spontaneous Mutagenesis | E. coli | Base substitutions | Tryptophan prototrophy | RecA, Pol V | [15] |

| Stationary-Phase Mutagenesis | P. putida | Frameshifts, base substitutions | Growth on phenol | Pol IV, Pol V, RpoS | [15] |

Note: An asterisk () denotes loss or inactivation of the gene. MMR: Mismatch Repair.*

Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Inducing and Quantifying the SOS Response

Principle: Measure SOS induction by quantifying the derepression of a reporter gene (e.g., sfiA::lacZ or recA::gfp) after controlled DNA damage [18].

Method:

- Culture and Stressor: Grow an E. coli strain containing the SOS reporter to mid-log phase. A common inducing stressor is UV irradiation at 254 nm.

- Induction: Harvest cells, wash, and resuspend in saline. Expose to a calibrated UV dose (e.g., 10-50 J/m²). Keep a non-irradiated control in the dark.

- Incubation and Measurement: Post-irradiation, dilute cells in fresh medium and incubate with shaking. For

lacZfusions, measure β-galactosidase activity at timed intervals (0, 30, 60, 90 mins) [18]. Forgfpfusions, monitor fluorescence via microscopy or flow cytometry to capture single-cell, oscillatory induction patterns [18]. - Controls: Include a

recAorlexAdeficient mutant as a negative control.

Protocol 2: Measuring Stress-Induced Mutagenesis Using the Lac+ System

Principle: Quantify the rate of reversion mutations that allow Lac- cells to utilize lactose as a sole carbon source during starvation [15].

Method:

- Starvation Setup: Plate a large number of Lac- E. coli cells (e.g., FC40 strain) onto minimal media plates with lactose as the only carbon source. Include a low concentration of a poor carbon source (e.g., 0.05% glycerol) to allow limited growth before starvation sets in.

- Incubation: Incubate plates for several days. Visible colonies are Lac+ revertants that arose during starvation.

- Quantification: Count the number of Lac+ revertants that appear over time. Mutation rates can be calculated using the Ma-Sandri-Sarkar maximum likelihood method or fluctuation analysis on parallel cultures.

- Validation: Confirm the genetic dependencies of the observed mutagenesis by repeating the assay with isogenic strains lacking key genes like

dinB(Pol IV) orrecA[15].

Signaling Pathway & Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Diagram Title: SOS Response Signaling Pathway

Diagram Title: Workflow for SOS and Mutagenesis Assays

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating SOS and Mutagenesis

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Key Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

recA::gfp / lexA::gfp transcriptional fusions |

Reporter Strain | Visualizes SOS induction dynamics in real-time at single-cell resolution. | Detecting oscillatory SOS pulses after UV damage [18]. |

ΔrecA / ΔlexA mutant strains |

Genetic Control | Confirms SOS-dependence of an observed phenotype (e.g., mutagenesis). | Determining if antibiotic-induced mutagenesis requires a functional SOS response [18]. |

ΔdinB (Pol IV) / ΔumuDC (Pol V) mutants |

Genetic Tool | Dissects the specific role of error-prone TLS polymerases in mutagenesis. | Identifying the polymerase responsible for specific mutation signatures under stress [15] [17]. |

| UV Crosslinker (254 nm) | Laboratory Equipment | Provides a controlled, reproducible DNA-damaging stimulus to induce the SOS response. | Standardized induction of the SOS pathway for mechanistic studies [20]. |

| Error-Prone Polymerase Inhibitors | Pharmacological Agent | Experiments with novel therapeutics aimed at suppressing stress-induced mutagenesis. | Testing if inhibiting Pol IV/V reduces the emergence of antibiotic resistance [16]. |

Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) acts as a molecular "conveyor belt," enabling the rapid spread of antibiotic resistance genes among bacterial populations. Unlike vertical gene transfer (from parent to offspring), HGT allows for the movement of genetic information between organisms, a process that includes the spread of antibiotic resistance genes among bacteria, fueling pathogen evolution [21]. This continuous flow of genetic material is a primary driver of the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis, making it a critical focus for therapeutic research.

Mechanisms of the HGT Conveyor Belt

The HGT conveyor belt operates through three well-understood genetic mechanisms, each with distinct functionalities. The table below summarizes these core processes.

Table 1: Core Mechanisms of Horizontal Gene Transfer

| Mechanism | Description | Key Components | Primary Role in AMR Spread |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformation [21] [22] | Bacteria take up and integrate free environmental DNA from dead, degraded bacteria. | Competence-specific proteins, DNA binding proteins, RecA proteins | Allows for the acquisition of resistance genes from the environment, including from non-pathogenic bacteria. |

| Conjugation [21] [22] [23] | Direct cell-to-cell transfer of genetic material via a conjugative pilus. | Conjugative plasmids, conjugative transposons, mobilizable plasmids | The most common mechanism for inter-species transfer of resistance plasmids (R-plasmids). |

| Transduction [21] [22] | Bacteriophages (bacterial viruses) accidentally package and transfer bacterial DNA from one cell to another. | Bacteriophages (lytic and temperate) | Transfers resistance genes between bacteria of the same or closely related species. |

To elucidate the logical relationships between these mechanisms and their collective impact on antimicrobial resistance, the following diagram outlines the HGT pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Research into HGT mechanisms requires specific reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials for studying the conveyor belt of resistance genes.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for HGT Experiments

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in HGT Research |

|---|---|

| Competence-Inducing Media [22] | Stimulates natural competence in bacteria (e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae) for transformation studies. |

| Selective Antibiotics [21] [22] | Used in growth media to select for and isolate transformants/transconjugants that have acquired a resistance marker. |

| Conjugative Plasmids (e.g., F-factor, R-plasmids) [22] [23] | Serve as mobile genetic elements to study the mechanism, efficiency, and regulation of conjugation. |

| Bacteriophage Lysates [22] [24] | Used in transduction experiments to infect donor and recipient strains for generalized or specialized transduction. |

| DNA Binding Dyes (e.g., Ethidium Bromide, DAPI) | Visualize DNA uptake during transformation or track the location of plasmids within cells. |

| Anti-SprB Antibody [25] | Used in tethered-cell analysis to study the mechanics of gliding motility and the Type IX Secretion System (T9SS) in certain Bacteroidetes. |

| PCR Reagents & Primers | Amplify and detect specific resistance genes before and after HGT events to confirm successful transfer. |

Troubleshooting Common HGT Experimental Challenges

This section addresses specific issues researchers might encounter during experiments related to HGT and antibiotic resistance.

FAQ 1: Why is my conjugation experiment yielding no transconjugants?

Problem: Despite setting up a conjugation between a donor strain (with an R-plasmid) and a recipient strain, no antibiotic-resistant transconjugant colonies are growing on the selective plates.

Solution:

- Verify Strain Viability: Ensure both donor and recipient strains are viable and in the correct growth phase (typically mid- to late-log phase) for optimal pilus formation and mating efficiency [22].

- Optimize Mating Conditions: Increase the mating time (e.g., from 1 hour to 4-18 hours) and use a non-selective, nutrient-rich solid or liquid medium for the conjugation step. Gently resuspend cells without vortexing to avoid shearing the conjugation pili.

- Check Antibiotic Selectivity: Confirm that the selective antibiotics in your plate effectively kill the donor and recipient controls. The recipient must be resistant to an antibiotic that inhibits the donor, and the selective plate must contain an antibiotic for which the R-plasmid confers resistance to the recipient.

- Confirm Plasmid Mobility: Ensure the plasmid in the donor strain is indeed a conjugative plasmid, not a non-mobilizable one [23].

FAQ 2: How can I confirm that resistance was acquired via natural transformation and not spontaneous mutation?

Problem: After co-incubating a sensitive strain with DNA from a resistant strain, resistant colonies appear, but you need to rule out spontaneous mutation as the cause.

Solution:

- Include Critical Controls:

- DNA Control: Plate the naked DNA on the selective medium to confirm it cannot grow.

- Recipient Control: Plate the recipient strain without added DNA on the selective medium to check for pre-existing resistant mutants.

- DNase Control: Treat the DNA with DNase before adding it to the recipient. This should completely abolish the appearance of resistant colonies, confirming that the resistance is DNA-dependent [22].

- Molecular Confirmation: Use PCR to amplify the specific resistance gene from the transformed colonies. Sanger sequencing of the amplicon can confirm it is identical to the gene from the donor DNA, not a mutated version.

FAQ 3: What methods can I use to quantify the rate of HGT in my experimental system?

Problem: You need to move beyond a qualitative "yes/no" for HGT and measure the frequency of transfer events.

Solution:

- Standard Calculation: For conjugation and transformation, the transfer frequency is typically calculated as the number of transconjugants or transformants divided by the number of recipient cells (or total viable count) at the end of the mating/transformation period [23].

- Experimental Workflow: The process involves performing the HGT experiment, plating appropriate dilutions on selective media to count transconjugants/transformants, and plating on non-selective media to determine the total recipient cell count.

- Use of Fluorescent Reporters: Engineer donor and recipient strains with fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP, RFP). The transfer of a plasmid carrying a fluorescence gene can be quantified over time using flow cytometry, providing a high-throughput method to measure HGT dynamics.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps for a standard HGT quantification experiment.

Advanced Techniques & Novel Interventional Strategies

Beyond basic HGT study, current research focuses on disrupting this conveyor belt to combat AMR. The table below summarizes several advanced strategies.

Table 3: Novel Strategies to Combat Horizontal Gene Transfer of Resistance

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Experimental Protocol Highlights |

|---|---|---|

| Phage Therapy [24] | Use of bacteriophages to specifically infect and lyse antibiotic-resistant bacteria, reducing the reservoir of resistance genes. | "Training" phages via experimental evolution for 30 days to expand host range against multi-drug resistant pathogens like Klebsiella pneumoniae [24]. |

| CRISPR-Cas Gene Editing [26] | Delivery of CRISPR-Cas systems to specifically target and cleave resistance genes in bacterial populations, "re-sensitizing" them to antibiotics. | Design of sgRNAs to target specific resistance gene sequences (e.g., blaNDM-1) and delivery via plasmids or phages to bacterial communities. |

| Antibiotic Potentiators [27] | Use of non-antibiotic compounds that impair bacterial resistance mechanisms (e.g., efflux pump inhibition, enzyme blockade), restoring efficacy of existing antibiotics. | Checkerboard assays to measure synergy (FIC Index) between a potentiator (e.g., a natural terpene) and an antibiotic against a resistant strain. |

| Precision Prescribing [28] | Computerized alerts using EHR data to guide clinicians toward narrow-spectrum antibiotics for low-risk patients, reducing selective pressure. | Implementation of clinical decision support systems that use hospital-specific data to assess individual patient risk for resistant infections. |

Global Resistance Data & The Imperative for Action

Understanding the scale of the AMR problem underscores the importance of HGT research. Recent data from the World Health Organization (WHO) quantifies the threat.

Table 4: WHO Global Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance (2025 Report) [2]

| Pathogen | Key Resistance Finding | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Over 55% are resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (first-choice treatment) globally. | Leads to untreatable pneumonia and sepsis; a prime carrier of transmissible resistance plasmids. |

| Escherichia coli | Over 40% are resistant to third-generation cephalosporins globally. Resistance to fluoroquinolones and carbapenems is rising. | A major cause of drug-resistant urinary tract and bloodstream infections. |

| Acinetobacter spp. | Increasing carbapenem resistance, narrowing treatment options to last-resort antibiotics. | Notorious for causing hard-to-treat hospital-acquired infections. |

| Aggregate | 1 in 6 laboratory-confirmed bacterial infections in people worldwide were resistant to antibiotic treatments in 2023. | Illustrates the pervasive and systemic nature of the AMR crisis, driven largely by HGT. |

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

My bacterial isolates are showing unexpectedly high resistance rates in my assay. What could be the cause?

Answer: Unexplained spikes in resistance can often be traced to contamination or undisclosed antibiotic exposure in your research model. First, verify the purity of your bacterial stocks through re-streaking and single-colony isolation. For in vivo studies, investigate potential environmental sources. In one comprehensive study, high resistance rates of 27.95% were noted, particularly against pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae [29]. Implement stricter environmental controls and audit animal feed and water for antimicrobial agents, as uncontrolled antibiotic use in livestock can contribute to resistance that enters the research setting [30].

What is the best way to model environmental antibiotic residue exposure in my research?

Answer: To accurately model environmental exposure, simulate real-world conditions. Prepare sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics based on concentrations reported in agricultural runoff or wastewater effluent. In laboratory settings, studies show that exposing bacteria to concentrations as low as 1/10 the MIC in chemostats over serial passages can effectively simulate the selection pressure found in contaminated environments. This approach aligns with the One Health principle that environmental contamination is a key driver of resistance [31] [32].

How can I improve the translational value of my antibiotic therapy study from animals to humans?

Answer: Adopt a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling approach that integrates data across species. Ensure your animal model accounts for the interconnectedness of human and animal health, a core tenet of the One Health approach [31] [30]. Furthermore, incorporate host immune response metrics and gut microbiome analysis into your endpoints. Surveillance data coordinated by institutions like the University of Nairobi shows that common bacteria in animals and humans, such as E. coli and S. aureus, exhibit similar resistance patterns (e.g., 60-70% for E. coli), highlighting the shared resistance landscape [30].

My research on a new drug combination is being confounded by pre-existing resistances in my clinical isolates. How can I screen for this more effectively?

Answer: Implement a pre-screening protocol using genomic and phenotypic characterization. Begin with rapid molecular techniques like PCR to detect common resistance genes (e.g., NDM-1, ESBLs). Follow this with phenotypic confirmation using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing. National policies, such as India's AMR containment policy, recommend establishing robust AMR surveillance systems that combine these methods to generate reliable data for informing empirical therapy [33]. This two-tiered approach helps clarify whether observed treatment failures are due to pre-existing resistance or other experimental factors.

Quantitative Data on Resistance and Therapy

Table 1: Documented Resistance Rates of Common Pathogens (Surveillance Data)

| Pathogen | Common Resistance Profile | Documented Resistance Rate | Key Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Resistance to commonly used treatments in newborns [30] | 70-80% [30] | A major concern for neonatal infections [30] |

| Escherichia coli | Resistance to frequently used antibiotics [30] | 60-70% [30] | Prevalent in community and healthcare settings [30] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Resistance to available antibiotics (e.g., MRSA) [29] [30] | ~50% [30] | A serious problem in hospital settings; MRSA prevalence in India was 41% [33] |

| Overall Resistance (across various classes and pathogens) | Highest rates noted in penicillins and cephalosporins [29] | 27.95% (average in a study of 1,050 observations) [29] | Resistance varies widely across antibiotic classes [29] |

Table 2: Key Findings from a Comparative Study on Antibiotic Therapy

| Study Parameter | Findings from 1,050 Patient Records [29] |

|---|---|

| Most Prescribed Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic | Ceftriaxone (27.9%) |

| Patients with History of Previous Infection | 67.5% |

| Patients Receiving High-Dose Drugs | 36.5% |

| Average Treatment Effectiveness | 77.43% |

| Average Treatment Safety Rate | 84.77% |

| Average Diagnosis Delay | 4 days |

| Statistical Correlation | Significant associations were found between prior antibiotic use and the development of resistance across different antibiotic classes. |

Experimental Protocols for One Health Research

Protocol 1: Integrated One Health AMR Surveillance

Objective: To establish a methodology for tracking antimicrobial resistance patterns across human, animal, and environmental samples in a defined region.

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Concurrently collect clinical isolates from human healthcare settings, livestock (e.g., poultry, cattle), and environmental sources (e.g., soil, water bodies near farms).

- Laboratory Analysis:

- Isolate and identify major bacterial pathogens (E. coli, K. pneumoniae, S. aureus) using standard microbiological and biochemical methods.

- Perform Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) using Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion or broth microdilution to determine MICs for a core panel of antibiotics (e.g., penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones).

- Preserve isolates for genetic analysis.

- Data Integration and Analysis:

- Create a centralized database to log resistance profiles from all three sectors.

- Use spatial mapping to visualize hotspots of specific resistance patterns.

- Perform genetic sequencing (e.g., whole-genome sequencing) on a subset of isolates with similar resistance profiles from different sectors to investigate the genetic relatedness and potential transmission of resistance genes.

This protocol operationalizes the collaborative, multisectoral approach recommended by the One Health strategy [31] [30] [32].

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Impact of Sub-therapeutic Antibiotic Exposure

Objective: To determine how sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics in the environment, mimicking agricultural runoff, select for resistant bacterial populations.

Methodology:

- Strain Preparation: Select environmental or commensal bacterial strains (e.g., E. coli).

- Exposure Model:

- Set up continuous-culture bioreactors (chemostats) with low-nutrient media to simulate natural aquatic environments.

- Continuously introduce a sub-therapeutic dose (e.g., 1/10 to 1/100 of the MIC) of a target antibiotic (e.g., tetracycline, used in agriculture).

- Maintain control chemostats without antibiotic pressure.

- Monitoring and Endpoint Analysis:

- Sample populations at regular intervals over several weeks.

- Quantify the MIC of the population over time to track resistance development.

- Use selective plating to enumerate the proportion of resistant bacteria.

- At endpoint, sequence the genomes of evolved populations to identify acquired resistance mutations or genes.

This methodology directly addresses the environmental dimension of One Health, where contamination exerts selective pressure for AMR [31] [32].

Visualizing the One Health Approach to AMR

Diagram 1: One Health AMR Drivers

Diagram 2: AMR Research Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for AMR Research

| Item | Function / Application in AMR Research |

|---|---|

| Mueller-Hinton Agar/Broth | The standardized medium recommended by CLSI and EUCAST for performing Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) to ensure reproducible and comparable MIC results. |

| Antimicrobial Powder Standards | High-purity antibiotic powders used to prepare custom solutions for creating concentration gradients in MIC assays and for use in disk diffusion tests. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Systems | Molecular tools used for precise knockout or modification of specific bacterial resistance genes to study their function and contribution to the resistant phenotype. |

| Whole Genome Sequencing Kits | Reagents for preparing bacterial DNA libraries to sequence entire genomes, allowing for the identification of known and novel resistance mutations and genes. |

| Biofilm Reactors & Stains | Systems (e.g., flow cells, Calgary biofilm devices) and dyes (e.g., crystal violet, LIVE/DEAD stains) to grow and quantify biofilms, which are key to understanding chronic, resistant infections. |

| Animal Infection Models | Specific pathogen-free (SPF) rodent models (e.g., mouse, rat) used to study the in vivo efficacy of new therapeutic agents and the pathogenesis of resistant infections. |

| Data Integration Software | Bioinformatics platforms (e.g., CLC Genomics Workbench, Geneious) and statistical software (e.g., R, SPSS) essential for analyzing complex datasets from integrated One Health surveillance [33] [29]. |

Resistance-Resistant Therapeutics: From Conceptual Frameworks to Clinical Applications

The escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most pressing challenges in modern medicine. According to recent WHO data, one in six laboratory-confirmed bacterial infections globally were resistant to antibiotic treatments in 2023, with resistance rising in over 40% of monitored pathogen-antibiotic combinations [2]. This alarming trend has stimulated research into innovative approaches that move beyond directly killing bacteria to instead inhibit their evolutionary capacity to develop resistance. A prime target in this endeavor is the bacterial SOS response—an inducible DNA repair network that promotes genetic diversity and adaptability under stress [34] [17]. When antibiotics trigger DNA damage, either directly or indirectly through metabolic byproducts like reactive oxygen species (ROS), bacteria activate this sophisticated emergency response system [35] [19]. The SOS pathway not only facilitates repair of damaged DNA but also regulates error-prone DNA polymerases that introduce mutations, thereby accelerating the evolution of resistance mechanisms [34] [17]. This technical resource provides troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and strategic insights for researchers developing interventions that target bacterial evolvability through disruption of mutagenic stress responses.

Core Mechanism: The SOS Response Pathway

The SOS response is a highly regulated bacterial stress adaptation mechanism. Understanding its components and activation dynamics is fundamental to developing effective inhibitors.

Molecular Regulation

The SOS response is primarily regulated by two key proteins: LexA (repressor) and RecA (inducer) [17] [19]. During normal growth, LexA forms a dimer that binds to operator sequences (SOS boxes) in the promoter regions of more than 50 genes, maintaining the SOS regulon in a repressed state [17]. When DNA damage occurs, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) gaps accumulate, providing a platform for RecA nucleation. RecA binds to ssDNA, forming nucleoprotein filaments (RecA*) that activate LexA's self-cleavage capacity [17]. This cleavage inactivates LexA, reducing its affinity for DNA and leading to derepression of SOS genes [17] [19].

The following diagram illustrates the core SOS response pathway and potential inhibition points:

Temporal Regulation of SOS Genes

SOS gene expression follows a precise temporal sequence that reflects their functional priorities [17]. Early-phase genes include those involved in error-free repair mechanisms, such as nucleotide excision repair (uvrA, uvrB) and homologous recombination (recA, recN). Mid-phase genes include those encoding DNA polymerase II (polB) and polymerase IV (dinB), along with the cell division inhibitor sulA. The late-phase response features the error-prone DNA polymerase V (umuC, umuD), which facilitates translesion synthesis at the cost of increased mutagenesis [17]. This temporal regulation ensures that error-prone mechanisms are deployed only when damage is extensive and persistent.

Research Reagent Solutions: Key Molecular Targets and Inhibitors

The table below summarizes prime targets for inhibiting SOS-mediated evolvability and characterized inhibitor compounds:

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for SOS Pathway Inhibition

| Target Protein | Known Inhibitors | Mechanism of Action | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| RecA [34] | Suramin, suramin-like agents [34] | Disassembles RecA-ssDNA filaments [34] | Block SOS induction; reduce recombination |

| 2-amino-4,6-diarylpyridine [34] | ATPase inhibition [34] | Prevent RecA activation | |

| Zinc acetate [34] | Inhibits LexA cleavage [34] | Indirect SOS suppression | |

| Peptide 4E1 (RecX-like) [34] | Filament disassembly [34] | Targeted RecA disruption | |

| LexA [34] | 5-amino-1-(carbamoylmethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-carboxamide [34] | Inhibits self-cleavage [34] | Block SOS derepression |

| Boron-containing compounds [34] | Interacts with catalytic Ser-119 [34] | LexA cleavage inhibition | |

| Pol V (UmuD2C) [34] | RecA D112R/N113R mutant [34] | Disrupts RecA-PolV interaction [34] | Study mutasome formation |

| SSB Protein [34] | Small molecules [34] | Disrupt SSB protein interfaces [34] | Impair replication/repair |

| RecBCD [34] | Sulfanyltriazolobenzimidazole NSAC1003 [34] | Binds RecB ATP-binding site [34] | Inhibit DNA end resection |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol: Measuring SOS Inhibition in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Background: This protocol adapts methodology from studies investigating SOS function in P. aeruginosa during ciprofloxacin exposure [36]. It enables quantification of how SOS inhibition affects competitive fitness and resistance development.

Materials:

- Wild-type P. aeruginosa PAO1 (WT)

- Isogenic SOS-uninducible LexA S125A mutant (prevents autocleavage) [36]

- M9KB broth medium

- Ciprofloxacin (stock solution: 1 mg/mL in water/DMSO)

- Gentamicin (for selection)

- Luminescence plate reader (if using reporter strain)

Method:

- Strain Preparation: Inoculate separate colonies of WT and LexA mutant into M9KB broth. Grow overnight at 37°C with shaking [36].

- Competition Setup: Combine exponential-phase cultures at varying initial ratios (e.g., 70:30, 50:50, 30:70 WT-to-mutant). Use gentamicin resistance (present in the LexA mutant) as a selectable marker [36].

- Antibiotic Exposure: Dilute mixed cultures 100-fold into fresh M9KB containing sublethal ciprofloxacin (e.g., 48 µg/L, which induces ~50% mortality and maximal SOS response) [36]. Include antibiotic-free controls.

- Growth and Plating: Incubate cultures for 24 hours at 37°C. Dilute and plate on M9KB agar with and without gentamicin to enumerate each strain [36].

- Fitness Calculation: Calculate wild-type fitness as the ratio of Malthusian parameters for WT versus mutant: m = [ln(Nf/N0)]WT / [ln(Nf/N0)]LexA where N0 and Nf are initial and final densities [36].

- SOS Expression Monitoring: For temporal analysis, use a luminescent SOS reporter (e.g., plexA::lux) to measure induction kinetics under treatment [36].

Troubleshooting: If fitness differences are minimal, verify ciprofloxacin concentration and ensure proper marker selection. The LexA S125A mutation provides a clean genetic SOS blockade without pleiotropic effects [36].

Protocol: Assessing SOS-Independent Resistance Evolution in E. coli

Background: Recent findings demonstrate that RecA deletion can unexpectedly accelerate β-lactam resistance through SOS-independent mechanisms involving ROS accumulation and impaired DNA repair [37]. This protocol quantifies this alternative evolutionary path.

Materials:

- E. coli MG1655 (WT) and isogenic ΔrecA mutant (JW2669-1 from CGSC) [37]

- LB broth and agar

- Ampicillin (stock: 50 mg/mL in water)

- ROS detection dye (e.g., H2DCFDA)

- Rifampicin plates for mutation frequency

- 96-well deep culture plates

Method:

- Strain Validation: Confirm RecA deletion phenotype via UV sensitivity compared to WT [37].

- Single Exposure Resistance: Grow overnight cultures of WT and ΔrecA. Dilute 1:100 into fresh LB containing ampicillin (50 µg/mL, ~10× MIC). Incubate 8 hours at 37°C with shaking [37].

- MIC Determination: Measure post-exposure MIC using broth microdilution. Compare to pre-exposure MIC [37].

- Mutation Rate Analysis: Distribute 96 independent cultures of WT and ΔrecA in 96-well plates. Grow with/without ampicillin for 8 hours. Plate on rifampicin to select resistant mutants. Use maximum likelihood estimation to calculate mutation rates [37].

- ROS Detection: Load parallel cultures with H2DCFDA (10 µM). Measure fluorescence intensity during ampicillin exposure to quantify ROS accumulation [37].

Expected Results: ΔrecA strains typically show ≥20-fold ampicillin MIC increase after single exposure, correlated with elevated ROS and increased mutation supply [37].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Table 2: Troubleshooting SOS Inhibition Experiments

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No fitness cost with SOS inhibition | Suboptimal antibiotic concentration; insufficient DNA damage induction | Titrate antibiotic to achieve ~50% mortality; use known SOS inducers (e.g., ciprofloxacin) [36] |

| High variability in competition assays | Inconsistent initial ratios; cross-contamination | Use multiple independent colonies; verify mixing ratios by plating; maintain sterile technique [36] |

| Unexpected resistance in SOS-deficient strains | SOS-independent pathways; ROS-mediated mutagenesis | Include ROS scavengers (e.g., thiourea); complement with functional RecA; test multiple replicates [37] |

| Poor inhibitor potency in vivo | Limited cellular uptake; efflux pump activity | Use chemical analogs with improved permeability; employ efflux pump deficient strains [34] |

| Toxicity of SOS inhibitors | Off-target effects on host/human cells | Determine selective index (bacterial vs. mammalian cell toxicity); use targeted delivery approaches [34] |

Advanced Concepts: Resistance Beyond SOS

While the SOS response represents a prime target, recent research reveals additional evolutionary pathways that can complicate therapeutic strategies:

SOS-Independent Resistance Mechanisms: Studies demonstrate that E. coli lacking RecA can rapidly develop stable, multi-drug resistance after a single β-lactam exposure through SOS-independent pathways [37]. This occurs through a two-step process: (1) RecA deficiency impairs DNA repair and represses antioxidant defenses, leading to ROS accumulation and increased mutational supply; and (2) antibiotic pressure selectively enriches resistant variants from this hypermutable population [37]. This highlights the importance of combinatorial approaches that target both specific resistance pathways and general mutational mechanisms.

Alternative Evolutionary Strategies: Research in P. aeruginosa indicates that the SOS response primarily provides short-term fitness advantages under antibiotic stress rather than accelerating long-term adaptation [36]. During 200-generation selection experiments with ciprofloxacin, SOS-proficient and deficient strains showed similar resistance evolution trajectories, with SOS expression actually decreasing during adaptation [36]. This suggests bacteria may downreginate mutagenic pathways once initial resistance is acquired.

Exploiting Resistance Mechanisms: Innovative approaches are exploring how to "hack" bacterial resistance mechanisms for therapeutic benefit. In Mycobacterium abscessus, researchers engineered a florfenicol prodrug that is activated by Eis2, a WhiB7-regulated resistance protein [12]. This creates a perpetual cascade where antibiotic activation induces more resistance proteins, which in turn generate more active drug, effectively turning the resistance mechanism against the bacterium [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why target bacterial evolvability rather than simply developing new antibiotics?

A: Inhibiting evolvability addresses the fundamental problem of resistance development rather than playing "catch-up" with resistant strains. By suppressing mutagenic stress responses like the SOS pathway, we can potentially extend the therapeutic lifespan of existing antibiotics and reduce the emergence of multi-drug resistant strains [34] [33].

Q2: What is the relationship between SOS response and bacterial persistence?

A: The SOS response contributes to bacterial persistence through multiple mechanisms. It can induce toxin-antitoxin systems (like TisB/IstR in E. coli) that promote dormancy and regulate biofilm formation, which provides physical protection and creates heterogeneous microenvironments that stimulate SOS induction [19]. Persisters exhibit transient tolerance to antibiotics and can serve as a reservoir for resistance development.

Q3: Are there species-specific differences in SOS regulation that might affect inhibitor design?

A: Yes, significant variations exist. While E. coli and P. aeruginosa have canonical LexA/RecA systems, Mycobacterium tuberculosis utilizes a different mutagenic polymerase (DnaE2) under LexA control [34]. Some species like Streptococcus pneumoniae lack LexA entirely and use alternative regulatory cascades [34]. Effective inhibitor design must consider these species-specific differences.

Q4: What are the main challenges in developing SOS inhibitors for clinical use?

A: Key challenges include: (1) achieving sufficient specificity to avoid host toxicity, particularly given RecA's structural similarities to eukaryotic RAD51; (2) ensuring bacterial permeability and retention; (3) preventing rapid resistance to the inhibitors themselves; and (4) navigating complex regulatory pathways that may vary between bacterial species [34] [17].

Q5: How do sublethal antibiotic concentrations influence resistance development?

A: Sublethal antibiotic exposure can induce stress responses (including SOS) that increase mutation rates and promote horizontal gene transfer [36] [19]. This emphasizes the importance of maintaining adequate dosing regimens and complete treatment courses to minimize the emergence of resistance.

Conceptual Framework: FAQs on Core Principles

FAQ 1: What are evolutionary steering and collateral sensitivity in the context of antibiotic resistance?

Answer: Evolutionary steering is a therapeutic strategy that aims to control the evolution of a pathogen population by deliberately applying selective pressure with one drug. The goal is to direct the evolutionary trajectory of the population in a predictable way, steering it toward a state of vulnerability [38]. Collateral sensitivity (CS) is a specific, exploitable evolutionary trade-off where resistance to one antibiotic concurrently causes increased sensitivity to a second, unrelated antibiotic [39] [40]. When combined, these approaches can trap pathogens in an "evolutionary double bind," making it difficult for multidrug resistance to emerge [38] [39].

FAQ 2: What are the common genetic and physiological mechanisms behind collateral sensitivity?

Answer: Collateral sensitivity arises from pleiotropic mutations, where a single genetic change impacts multiple traits. The table below summarizes key mechanisms identified in bacterial pathogens.

Table 1: Common Mechanisms of Collateral Sensitivity

| Mechanism | Description | Example Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Altered Membrane Permeability | Mutations that decrease uptake of one drug may increase uptake of another [40]. | Increased sensitivity to a second antibiotic due to enhanced import. |

| Efflux Pump Regulation | Overexpression of a efflux pump to remove one drug can be energetically costly or alter transport of other compounds [40]. | Hypersensitivity to drugs not expelled by the overexpressed pump. |

| Modification of Drug Targets | A mutation that alters the target of drug A may destabilize its interaction with drug B [40]. | Resistance to drug A but sensitivity to drug B. |

| Resistance Enzyme Hijacking | A resistance enzyme that normally inactivates one drug can activate a prodrug, turning the resistance mechanism against the cell [12]. | perpetual amplification of the antibiotic's effect within the cell. |

FAQ 3: Why is the order of drug administration (drug sequence) so critical?

Answer: Collateral sensitivity networks are often directional. Resistance to Drug A may cause sensitivity to Drug B, but resistance to Drug B might not cause sensitivity to Drug A—it could even cause cross-resistance [39]. The effectiveness of evolutionary steering depends on using the correct sequence that creates a sustained vulnerability. Using the wrong sequence can select for multidrug-resistant clones and lead to therapeutic failure [38] [39].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

This section provides a detailed methodology for setting up and analyzing evolution experiments to identify and validate collateral sensitivity pairs.

Core Experimental Protocol: Laboratory Evolution and Sensitivity Profiling

Objective: To evolve resistance to a primary antibiotic and systematically identify collateral sensitivity to a panel of secondary antibiotics.

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa or other relevant pathogen [39].

- Antibiotics: Stock solutions of the primary selective antibiotic and a panel of secondary antibiotics for profiling.

- Growth Media: Appropriate liquid and solid media (e.g., Mueller-Hinton Broth).

- Equipment: Microplate readers, automated liquid handlers, incubators.

Procedure:

- Passage and Selection:

- Propagate multiple replicate populations of the bacterial strain in the presence of a sub-inhibitory concentration of the primary antibiotic (Drug A).

- Over successive generations, linearly increase the concentration of Drug A to select for highly resistant populations [39].

- Include control populations passaged without antibiotics.

Resistance Validation:

- After resistance stabilizes, isolate single clones from the evolved populations.

- Determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of Drug A for both the evolved clones and the ancestral strain to quantify the level of resistance.

Collateral Sensitivity Screening:

- Perform dose-response assays of the evolved clones and the ancestor against a panel of secondary antibiotics (Drugs B, C, D, etc.).

- Calculate the fold-change in MIC for each secondary drug. Collateral sensitivity is defined as a significant decrease (e.g., ≥ 4-fold) in the MIC of the secondary drug in the evolved clone compared to the ancestor [39].

Genomic Analysis:

- Sequence the whole genomes of clones showing strong collateral sensitivity.

- Identify mutations (SNPs, indels, amplifications) responsible for the primary resistance.

- Use genetic techniques (e.g., gene knockouts, complementation) to validate the role of identified mutations in causing both resistance and collateral sensitivity [39].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for identifying collateral sensitivity.

Protocol for Testing Evolutionary Stability

Objective: To determine if a identified collateral sensitivity relationship is stable or if pathogens can easily escape the trade-off.

Procedure:

- Evolutionary Challenge:

- Take a clone that is resistant to Drug A and collaterally sensitive to Drug B.

- Subject this clone to a second round of evolution, this time under pressure from Drug B. Start at sub-inhibitory concentrations and escalate over time [39].

- Outcome Analysis:

- Monitor populations for extinction, which indicates a stable trade-off that cannot be overcome.

- If populations survive, isolate clones and re-measure MICs for both Drug A and Drug B.

- A favorable outcome is re-sensitization, where resistance to Drug B causes renewed sensitivity to Drug A, maintaining the trade-off [39].

Table 2: Quantitative Data from a Model CS Study with P. aeruginosa

| Evolutionary Step | Strain / Population | MIC Piperacillin/Tazobactam (µg/mL) | MIC Streptomycin (µg/mL) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Ancestral Strain | X | Y | Wild-type susceptibility |

| After 1st Evolution | PIT-Resistant Clone | >X (e.g., 32-fold increase) | Collateral Sensitivity to Streptomycin | |

| After 2nd Evolution | STR-Adapted Clone | ~X (returns near baseline) | >Y | Re-sensitization to Piperacillin |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Evolutionary Steering Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| High-Complexity Barcoded Libraries | Uniquely tags individual bacterial cells to track clonal dynamics in large, heterogeneous populations [38]. | Essential for distinguishing pre-existing resistant clones from those acquiring de novo mutations. |

| Large-Capacity Culture Vessels (e.g., HYPERflask) | Supports growth of very large populations (10^8 – 10^9 cells) without re-plating bottlenecks [38]. | Maintains intra-tumour heterogeneity and allows selection of pre-existing resistant subclones. |

| Morbidostat / Evolver | Automated continuous culture devices that dynamically adjust antibiotic concentration to maintain a constant selective pressure [39]. | Ideal for conducting controlled, long-term evolution experiments. |

| Phenotypic Microarray Plates | Pre-configured 96-well plates with different antibiotics for high-throughput collateral sensitivity screening. | Dramatically speeds up the process of profiling evolved clones against a broad drug panel. |

| Clinical Isolate Panels | Collections of clinically relevant, multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens (e.g., CRKP, MRSA). | Ensures research findings are translationally relevant and reflect real-world resistance threats. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: Inconsistent or non-repeatable collateral sensitivity effects between replicate populations.

- Potential Cause: Stochastic evolution, where different mutations conferring resistance to the first drug arise in different replicates, and these distinct mutations have different collateral effects [39] [40].

- Solution:

- Increase the number of biological replicates.

- Use larger population sizes to ensure a more consistent representation of pre-existing genetic variation [38].

- Perform whole-genome sequencing on clones from all replicates to correlate specific resistance mutations with their resulting collateral sensitivity profiles.

Problem 2: Evolved populations develop multidrug resistance instead of showing collateral sensitivity.

- Potential Cause: The selected antibiotic pair does not have a strong trade-off, or the population size is large enough to allow for very rare double-resistant mutants to emerge [39].

- Solution:

- Re-screen for new antibiotic pairs that show stronger, ideally reciprocal, collateral sensitivity.

- Use higher concentrations of the second drug to more effectively eliminate singly-resistant cells.

- Consider applying both drugs in combination after initial steering to prevent outgrowth of doubly-resistant mutants [40].

Problem 3: Failure to contain resistance in an in vivo model despite success in vitro.

- Potential Cause: The complex host environment (immune system, spatial heterogeneity, pharmacokinetics) alters selective pressures and evolutionary dynamics.

- Solution:

- Optimize dosing schedules in animal models to match the timing of selective windows identified in vitro.

- Monitor bacterial population dynamics directly from the infection site over time, if possible.

- Account for pathogen physiology in vivo, which may differ from laboratory conditions.

Figure 2: Logical pathways showing optimal and suboptimal evolutionary steering.

What are antibiotic adjuvants and why are they a critical tool in combating antimicrobial resistance (AMR)?

Antibiotic adjuvants are non-antibiotic compounds that enhance the effectiveness of antibiotics when administered together. They represent a promising strategy to combat multi-drug resistant (MDR) pathogens by rescuing the efficacy of existing antibiotics rather than developing new ones from scratch. The primary value of adjuvants lies in their ability to overcome specific bacterial resistance mechanisms, thereby restoring the activity of antibiotics against resistant strains. This approach is particularly vital given the declining pipeline of new antibiotics and the rapid global spread of resistance [41] [42].

How is "synergy" defined and measured in antibiotic combination therapies?

In the context of antibiotic combinations, "synergy" occurs when the combined effect of two or more agents is greater than the sum of their individual effects. Several mathematical models and associated metrics are used to quantify this phenomenon:

- Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI): Based on the Loewe additivity model, where doses are assumed to be additive. An FICI of ≤0.5 is generally considered synergistic [43].

- Bliss Independence Model: Assumes drugs act independently and probabilistically. Synergy is declared when the observed combined effect exceeds the expected independent effect [43].

- Highest Single Agent (HSA) Model: The effect of the combination should be equal to the maximum of the effects of each drug used individually; any effect above this maximum indicates synergy [43].

- Minimax Effective Concentration Index (MECI): A newer metric designed for efficient identification of synergistic combinations, especially in high-dimensional screens involving many drugs [43].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Researchers

A. Screening and Identification

What are the primary experimental designs for screening synergistic combinations?

The table below summarizes common screening approaches:

| Method Name | Key Principle | Best Use Case | Sample Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Factorial (Checkerboard) | Tests all possible concentration combinations of drugs [43]. | Gold standard for 2-drug combinations. | Grows exponentially with drug count (e.g., 10^d for d drugs) [43]. |

| Normalized Diagonal Sampling (NDS) | Samples along diagonals in concentration space where ratios are fixed [43]. | High-throughput screening of multi-drug (≥3) combinations. | Scales linearly with drug count (e.g., m ⋅ 2^d samples) [43]. |

| Library Screening (Repurposing) | Tests approved drugs or known bioactives as potential adjuvants [44]. | Identifying non-obvious adjuvants from existing compound libraries. | Varies by library size. |

What computational tools can predict synergistic interactions?

Computational models can significantly reduce the experimental burden:

- Parametric Models (Dose, Pairs): Assume no higher-order interactions beyond pairs of drugs [43].

- Mechanistic Models: Utilize knowledge of underlying drug targets or gene expression data [43].

- MAGENTA Model: Leverages phenotypic information about the cell's response to antibiotics [43].

- Data-Driven Predictive Models: Trained on pair-wise data to predict higher-order combination effects [43].

B. Mechanisms and Reagents

What are the major classes of antibiotic adjuvants and their mechanisms?

Adjuvants are broadly classified based on their target and mechanism of action [42]:

| Adjuvant Class | Mechanism of Action | Representative Examples | Target Antibiotic/Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class I.A: Inhibitors of Active Resistance | Block specific resistance enzymes [42]. | β-lactamase inhibitors (e.g., clavulanic acid) [44] [42] | β-lactam antibiotics |

| Class I.B: Inhibitors of Passive Resistance | Overcome physiologic barriers like membrane permeability or efflux pumps [42]. | Efflux pump inhibitors [41] | Various (e.g., tetracyclines) |

| Class I.B (Extended) | Disrupt protective bacterial communities. | Biofilm disruptors [41] | Antibiotics used against chronic infections |

| Class II: Immunomodulators | Enhance the host's immune response to infection [42]. | Immunomodulatory peptides (e.g., LL-37) [42] | Used in combination with standard antibiotics |

Can you provide a specific example of a non-antibiotic adjuvant discovery?

Yes. A screen of a compound library identified the antiplatelet drug ticlopidine as a potent adjuvant. While it had no inherent antibiotic activity, it strongly synergized with the cephalosporin cefuroxime against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Its molecular target was identified as TarO, an enzyme in the early stage of wall teichoic acid biosynthesis in the S. aureus cell wall. Inhibiting TarO sensitizes MRSA to β-lactam antibiotics [44].

C. Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

We are not identifying synergistic combinations in our high-throughput screens. What could be wrong?

- Problem: The experimental design or synergy metric might not be appropriate for the number of drugs being tested.