Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling for Anti-infective Dose Optimization: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

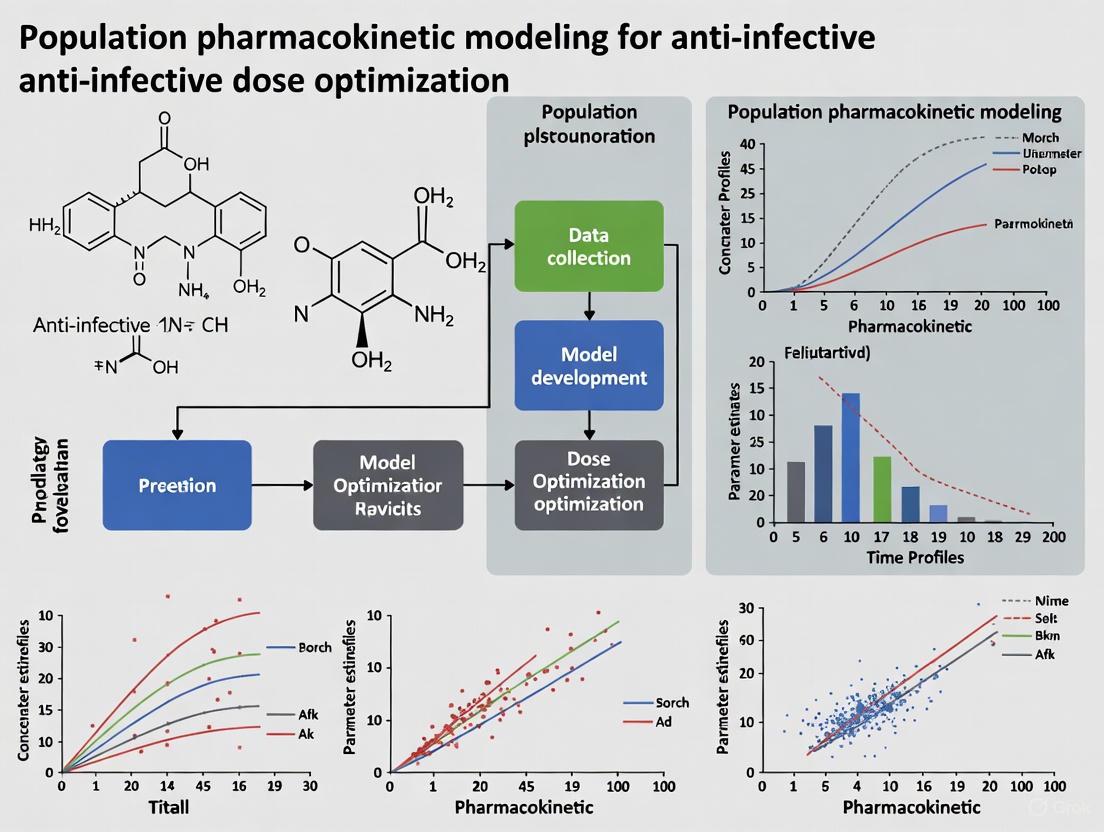

This article provides a comprehensive overview of population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) modeling and its critical application in optimizing anti-infective therapy, particularly in challenging patient populations like the critically ill.

Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling for Anti-infective Dose Optimization: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) modeling and its critical application in optimizing anti-infective therapy, particularly in challenging patient populations like the critically ill. It covers foundational principles, methodological approaches using nonlinear mixed-effects models (NLMEM), and software tools like NONMEM and Phoenix NLME. The content further addresses troubleshooting common issues, model validation strategies, and explores emerging trends such as machine learning automation and exposure-response analysis to achieve precise, personalized dosing that improves clinical outcomes and combats antimicrobial resistance.

Understanding Population PK Fundamentals and Its Critical Role in Anti-infective Therapy

Population pharmacokinetics (PopPK) is a critical discipline that studies the sources and correlates of pharmacokinetic variability in patient populations [1]. It utilizes nonlinear mixed-effects models (NLMEM) to simultaneously analyze data from all individuals in a study population, providing a powerful framework for understanding how drugs are absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted across diverse patient groups [2] [1]. This approach is particularly valuable in anti-infective dose optimization research, where optimizing drug exposure is essential for ensuring efficacy while minimizing toxicity and resistance development.

The "nonlinear" aspect of NLMEM refers to the fact that the dependent variable (e.g., drug concentration) is nonlinearly related to the model parameters and independent variables, while "mixed-effects" refers to the model parameterization that includes both fixed effects (population parameters assumed to be constant) and random effects (sample-dependent random variables) [1]. This modeling framework provides a robust solution for analyzing sparse, unbalanced data commonly encountered in clinical trials, where it may not be feasible to obtain extensive sampling from each patient [2]. By quantifying and explaining variability, PopPK models enable model-informed precision dosing, which is especially crucial for anti-infective drugs with narrow therapeutic windows.

Theoretical Foundations: Fixed Effects, Random Effects, and NLMEM

Fixed Effects

Fixed effects represent population-typical parameters that are assumed to remain constant each time data is collected [2]. These parameters describe the typical pharmacokinetic profile for the population, such as typical clearance (CL) or typical volume of distribution (Vd). Fixed effects can also include the influence of patient characteristics (covariates) on pharmacokinetic parameters. For example, a PopPK analysis of voriconazole identified that covariates such as continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), C-reactive protein, and specific liver enzymes significantly influence drug clearance [3]. Similarly, a piperacillin/tazobactam PopPK model identified estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) adjusted by body surface area and body weight as significant covariates affecting drug clearance and distribution [4].

Random Effects

Random effects account for the unpredictable variability in pharmacokinetic parameters between individuals, between occasions, and within the residual error [1]. These effects are modeled as random variables with distributions that must be specified, typically assuming a normal distribution with mean zero and variance ω² [2]. Random effects act as additional error terms that capture:

- Between-subject variability (BSV): Differences in parameters between individuals

- Between-occasion variability (BOV): Differences within the same individual on different occasions

- Residual unexplained variability (RUV): Remaining variability not accounted for by other model components

Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Models (NLMEM)

NLMEM integrates both fixed and random effects to provide a comprehensive framework for population analysis [1]. The mixed-effects approach offers a strategic compromise between ignoring data groupings entirely—which sacrifices valuable information—and fitting each group with a separate model, which requires significantly larger sample sizes [2]. This makes NLMEM particularly suitable for analyzing sparse data sets, such as those collected during routine therapeutic drug monitoring in clinical practice [3].

Table 1: Key Components of Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Models in Pharmacokinetics

| Component | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Model | Describes the typical concentration-time course | One-compartment, two-compartment models [4] |

| Fixed Effects | Population typical parameters | Typical clearance, volume of distribution [3] |

| Random Effects | Unexplained variability components | Between-subject, residual variability [1] |

| Covariate Models | Explain variability via patient factors | Renal function, body weight, genetic polymorphisms [3] [4] |

| Statistical Model | Accounts for random variability | Interindividual, interoccasion, residual error [1] |

Applications in Anti-Infective Dose Optimization Research

Voriconazole in COVID-19-Associated Pulmonary Aspergillosis

A recent PopPK study of voriconazole in patients with COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) demonstrated the clinical utility of NLMEM for dose optimization in complex patient populations [3]. The study developed a one-compartment model with first-order elimination to characterize voriconazole disposition, estimating an apparent clearance (CL/F) of 3.17 L/h and an apparent volume of distribution (V/F) of 135 L for a standard patient. Covariate analysis identified that CRRT, C-reactive protein, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, aspartate aminotransferase, and platelet count significantly influenced voriconazole clearance. Monte Carlo simulations based on the final model revealed that patients on CRRT required both higher loading doses and increased maintenance doses compared to those not on CRRT, providing evidence-based guidance for personalized dosing in this high-risk population [3].

Aztreonam-Avibactam Optimization through PopPK/PD

A population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling approach was used to optimize aztreonam-avibactam dose regimens for adult patients with serious gram-negative infections [5]. The final model, developed using data from 2,635 subjects, identified time-varying creatinine clearance as a key covariate on clearance for both drugs. The model was used to simulate exposures by infection type and renal function, estimating the joint probability of pharmacodynamic target attainment for phase 3 patients. Simulations demonstrated that the approved aztreonam-avibactam dose regimens achieved a joint probability of target attainment between 89% to >99% at steady state across renal function groups, confirming the adequacy of the proposed dosing strategy [5].

Piperacillin/Tazobactam Dosing Strategies

A PopPK analysis of piperacillin/tazobactam in healthy adults highlighted potential limitations in current dosing recommendations [4]. The study found that while the standard dosing regimen (4/0.5 g q6h with 30-minute infusion) achieved a 90% probability of target attainment for 50% fT>MIC at MIC values up to 4 mg/L in patients with normal renal function, this regimen often failed to achieve 90% PTA for more stringent targets (100% fT>MIC, 100% fT>4×MIC) or higher MICs, particularly in patients with enhanced renal function (eGFR ≥ 130 mL/min). These findings suggest that alternative strategies such as extended or continuous infusion may be necessary to optimize therapeutic outcomes, especially for less susceptible pathogens [4].

Table 2: Key Parameters from Recent Anti-Infective PopPK Studies

| Drug | Population | Structural Model | Key Covariates | Dosing Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voriconazole [3] | CAPA patients | One-compartment | CRRT, CRP, GGT, AST, PLT | Higher doses needed for CRRT patients |

| Aztreonam-Avibactam [5] | Adults with gram-negative infections | Two-compartment | Time-varying CrCl | Optimized regimens across renal function |

| Piperacillin/Tazobactam [4] | Healthy adults | Two-compartment | eGFR, Body weight | Standard dosing inadequate for enhanced renal function |

Experimental Protocols for Population PK Model Development

Data Collection and Preprocessing

The initial step in PopPK model development involves comprehensive data collection and preprocessing. Data should be scrutinized to ensure accuracy, with graphical assessment performed to identify potential problems or outliers [1]. During data cleaning, erroneous records may be identified and excluded if justified as outliers that would impair model development. Common data components include:

- Dosing information: Drug, dose, route, frequency, and duration

- Concentration measurements: Plasma, serum, or blood samples with precise timing

- Patient demographics: Age, sex, weight, height, body surface area

- Laboratory values: Renal function (creatinine, eGFR), liver function (ALT, AST, bilirubin)

- Clinical covariates: Disease status, concomitant medications, genetic polymorphisms

- Special circumstances: Renal replacement therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [3]

For voriconazole PopPK analysis, researchers collected extensive clinical data including demographic characteristics, biochemical indicators, concomitant medications, and CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 genotypes [3]. Drug concentrations were quantified using validated high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) methods with calibration curves demonstrating acceptable linearity over 0.1–30 mg/L [3].

Structural Model Development

The structural model describes the typical concentration-time course within the population [1]. For pharmacokinetic data, mammillary compartment models are predominant, with the number of compartments determined by the distinct exponential phases observed when plotting log concentration versus time [1]. Common structural models include:

- One-compartment model: Suitable for drugs with simple disposition characteristics

- Two-compartment model: Appropriate for drugs with distinct distribution and elimination phases

- Three-compartment model: Necessary for drugs with complex distribution patterns

Model selection is guided by diagnostic plots, objective function value (OFV) comparisons, and information criteria such as Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) [1]. The piperacillin/tazobactam PopPK analysis found that two-compartment models best described the concentration-time profiles for both drugs [4].

Statistical Model Development

The statistical model quantifies the random variability in the data, including between-subject variability, between-occasion variability, and residual unexplained variability [1]. Modelers must specify:

- IIV model: Typically exponential, proportional, or additive error models

- Residual error model: Additive, proportional, or combined error structures

Parameter estimation is typically performed using maximum likelihood methods, with the objective function value (OFV) providing a summary of how closely model predictions match the observed data [1].

Covariate Model Development

Covariate analysis identifies patient factors that explain variability in pharmacokinetic parameters [6]. This process typically involves:

- Identification of potential covariates based on biological plausibility

- Covariate screening using statistical methods and graphical analysis

- Model building with forward inclusion and backward elimination

- Model validation using diagnostic plots and statistical criteria

In the voriconazole PopPK analysis, covariates were tested using a stepwise approach with significance levels of p < 0.05 for forward inclusion and p < 0.01 for backward elimination [3].

Model Validation

Model validation evaluates the performance and predictive ability of the final PopPK model. Common techniques include:

- Goodness-of-fit plots: Observed vs. predicted concentrations, conditional weighted residuals vs. time or predictions [4]

- Visual predictive checks: Comparing the variability of simulations from the model against the variability observed in the data [7]

- Bootstrap analysis: Assessing the stability and precision of parameter estimates

- Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks: Accounting for variability in dosing regimens and sampling schedules

PopPK Model Development Workflow

Table 3: Essential Tools for Population Pharmacokinetic Research

| Category | Tool/Resource | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Modeling Software | NONMEM [1] | Industry-standard for population PK/PD modeling |

| Monolix [7] | User-friendly interface for mixed-effects modeling | |

| Berkeley Madonna [7] | Model visualization and interactive simulation | |

| Statistical Platforms | R [8] | Data preprocessing, visualization, and diagnostics |

| SAS [8] | Data management and statistical analysis | |

| Analytical Methods | HPLC [3] | Drug concentration quantification |

| UV detection [3] | Detection method for chromatographic analysis | |

| Genotyping Tools | Sangon Biotech kits [3] | Genomic DNA isolation and purification |

| Sanger sequencing [3] | CYP450 polymorphism identification | |

| Visualization Tools | Graphviz/DOT [7] | Diagram creation for model workflows |

| ColorBrewer [8] | Accessible color palette selection for scientific figures |

Visualization Principles for Effective Communication

Effective visualization is crucial for communicating PopPK model results to multidisciplinary teams [7]. Key principles include:

- Provide a clear message: Focus on the main insight or relationship

- Show the quantity of interest: Display the placebo-corrected treatment effect rather than separate effects

- Use intuitive colors: Apply colors consistently (e.g., green for positive response, red for adverse effects)

- Ensure accessibility: Select color palettes with sufficient contrast for colorblind readers [8]

- Indicate thresholds of interest: Mark clinical relevance thresholds (e.g., target concentrations, efficacy thresholds)

For PopPK visualizations specifically:

- Show model components individually to facilitate understanding

- Display both estimated responses and confidence intervals

- Illustrate the percentage of patients crossing efficacy or safety thresholds

- Use appropriate time intervals and indicate dosing events [7]

NLMEM Components Relationship

Population pharmacokinetics using nonlinear mixed-effects modeling provides a powerful framework for understanding drug disposition variability in patient populations. By integrating fixed effects (population-typical parameters), random effects (unexplained variability), and covariate relationships, PopPK models enable evidence-based dose optimization for anti-infective therapies. The continued advancement of PopPK methodologies, coupled with appropriate visualization and communication strategies, will further enhance model-informed precision dosing in clinical practice, ultimately improving therapeutic outcomes for patients with infectious diseases.

Critically ill patients represent a population with some of the highest risks for treatment failure and drug-related toxicity. The pathophysiological changes associated with critical illness significantly alter antimicrobial disposition, creating substantial challenges for achieving effective drug concentrations at the site of infection [9]. Failure of antimicrobial therapy in this vulnerable population has a direct impact on survival, making dose optimization a critical determinant of clinical outcomes [9]. The complex interplay of multiple factors observed in critically ill patients poses a significant challenge in predicting the pharmacokinetics of antimicrobials, rendering standard dosing regimens frequently inadequate [9] [10].

The foundation of precision dosing rests upon the relationship between pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) properties of antimicrobial agents. The optimal PK/PD parameter depends on the antimicrobial's bacterial activity pattern: (1) peak plasma concentration (Cpeak)/minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for antimicrobials with concentration-dependent activity; (2) cumulative percent of time that free drug concentration remains above the MIC (fT>MIC) for time-dependent antimicrobials; and (3) area under the concentration-time curve (AUC)/MIC for antimicrobials with both concentration- and time-dependent activity [9]. Understanding these relationships is essential for designing regimens that maximize bacterial killing while minimizing toxicity and resistance development.

Quantitative Foundations: Pathophysiological Factors Altering PK/PD

The pathophysiological changes occurring during critical illness profoundly impact all aspects of drug disposition. Table 1 summarizes the primary factors and their effects on key pharmacokinetic parameters.

Table 1: Pathophysiological Factors Altering Antimicrobial Pharmacokinetics in Critically Ill Patients

| Factor | Impact on Volume of Distribution (Vd) | Impact on Clearance (CL) | Most Affected Antimicrobial Classes | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic Inflammation/SIRS | Increased Vd for hydrophilic antibiotics due to capillary leakage and edema [9] | Reduced metabolic clearance due to cytokine-mediated downregulation of metabolic enzymes [9] | Hydrophilic antibiotics (β-lactams, glycopeptides, aminoglycosides); Voriconazole [9] | Higher initial loading doses often required; Altered maintenance dosing for hepatically cleared drugs [9] |

| Augmented Renal Clearance (ARC) | Minimal direct effect | Markedly increased renal clearance (CrCl >130 mL/min/1.73m²) [9] | Renally eliminated hydrophilic antibiotics (β-lactams, glycopeptides, aminoglycosides) [9] | Subtherapeutic exposure common; Requires higher doses or more frequent administration [9] |

| Hypoalbuminemia | Increased Vd for highly protein-bound drugs [9] | Increased clearance of highly protein-bound drugs [9] | Highly protein-bound antibiotics (ceftriaxone, ertapenem, teicoplanin) [9] | Increased free fraction may enhance efficacy but also increase toxicity risk [9] |

| Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) | Minimal direct effect (unless fluid overload) | Markedly decreased renal clearance [9] | Renally eliminated antibiotics [9] | Drug accumulation and toxicity risk; Requires dose reduction or extended dosing intervals [9] |

| Extracorporeal Therapies (CRRT, ECMO) | Variable effects depending on circuit components and flow rates [9] | Enhanced clearance during CRRT; Variable effects with ECMO [9] | hydrophilic antibiotics with low protein binding [9] | Highly variable drug removal; Therapeutic drug monitoring essential [9] |

Site-Specific Penetration Challenges

The primary infection site introduces additional variability in antibiotic exposure due to differing physiology that affects drug penetration. Table 2 summarizes key infection sites and their implications for dosing strategy.

Table 2: Infection Site Considerations and Dosing Implications

| Infection Site | PK Alteration | Representative Penetration Data | Dosing Strategy Adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bloodstream | Expanded Vd, Enhanced CL in sepsis [11] | Central compartment for distribution | Loading dose often required; Higher maintenance doses or continuous infusion [11] |

| Lung (ELF) | Variable penetration based on drug properties [11] | Piperacillin ELF:plasma ~0.50; Cefepime ELF:plasma ~1.04 [11] | Dose increase for hydrophilic agents with poor penetration [11] |

| CNS | Impaired permeability due to blood-brain barrier [11] | Limited penetration for many antibiotics | Maximal dosing regimens; Consider higher doses or alternative routes [11] |

| Soft Tissue | Variable based on perfusion and composition [11] | Contingent on body composition and drug properties | Consider obesity and tissue perfusion in dosing [11] |

Methodological Framework: Population PK Modeling Approaches

Core Components of Population PK Analysis

Population pharmacokinetic (popPK) modeling represents the methodological cornerstone of precision dosing by quantifying and explaining variability in drug concentrations [12] [13]. These models integrate data from multiple individuals, often pooled from several studies, to characterize typical population parameters while quantifying between-subject and residual variability [13]. The nonlinear mixed-effects modeling (NONMEM) approach first demonstrated by Sheiner et al. enables analysis of sparse clinical data, making it particularly valuable for critically ill populations where rich sampling is often impractical [14].

The structural model forms the foundation, typically employing compartmental approaches to describe the drug's ADME processes [13]. For example, piperacillin/tazobactam kinetics are optimally described by a two-compartment model, with parameters for clearance (CL), volumes of distribution (V1, V2), and intercompartmental clearance (Q) [4]. The statistical model then accounts for variability through between-subject variability (BSV), between-occasion variability (BOV), and residual unexplained variability (RUV) [13]. Covariate analysis identifies patient-specific factors (e.g., renal function, body size, inflammatory markers) that explain portions of the BSV, enabling more precise individualized predictions [13].

Population PK modeling follows a systematic process from data collection through model validation and simulation, with key considerations for critically ill patient covariates.

Experimental Protocol: Population PK Model Development

Protocol Title: Development of a Population Pharmacokinetic Model for Anti-infective Agents in Critically Ill Adults

Objective: To construct and validate a population PK model that characterizes the disposition of [Anti-infective Agent] in critically ill patients, identifying significant covariates that explain pharmacokinetic variability.

Materials and Requirements:

- Patient Population: Critically ill adults receiving [Anti-infective Agent] as part of standard care

- Sample Size: Typically 20-100 patients depending on expected variability [4] [3]

- Ethical Considerations: Approval from institutional review board with waiver of informed consent if using opportunistic sampling design

Methodology:

- Blood Sampling Protocol: Employ sparse sampling strategy (2-6 samples per patient) timed around drug administration. Collect demographic and clinical data including:

- Age, weight, height, body composition metrics

- Serum creatinine, albumin, C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Organ support modalities (CRRT, ECMO, vasopressors)

- Relevant genetic polymorphisms (e.g., CYP450 enzymes for voriconazole) [3]

Bioanalytical Methods:

- Quantify drug concentrations using validated method (e.g., HPLC, LC-MS/MS)

- Establish calibration curves and quality control samples

- Document precision and accuracy according to regulatory guidelines

Model Building:

- Develop structural model using nonlinear mixed-effects modeling (NONMEM)

- Test one-, two-, and three-compartment models

- Incorporate statistical model for between-subject and residual variability

- Perform stepwise covariate analysis evaluating clinical and demographic factors

Model Validation:

- Conduct bootstrap analysis to evaluate parameter precision

- Perform visual predictive checks to assess predictive performance

- Consider external validation if independent dataset available

Output Applications:

- Monte Carlo simulations to determine probability of target attainment (PTA) across patient subgroups [4]

- Development of model-informed precision dosing algorithms

- Identification of patient subgroups requiring alternative dosing strategies

Applied Research Tools: The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Antimicrobial PK/PD Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Representative Use in Critical Care PK |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Quantification of drug concentrations in biological matrices | High-sensitivity measurement of antimicrobial concentrations in plasma and tissue specimens [3] |

| Population PK Software (NONMEM, Monolix, R) | Nonlinear mixed-effects modeling | Development of population PK models from sparse clinical data [4] [3] |

| Monte Carlo Simulation Software | Prediction of probability of target attainment | Simulation of dosing regimens across virtual patient populations [4] |

| In Vitro Infection Models | Simulation of human PK profiles in laboratory setting | Assessment of bacterial killing and resistance prevention with human-simulated dosing regimens |

| Biomarker Assays (CRP, Procalcitonin, Cytokines) | Quantification of inflammatory response | Correlation of inflammatory status with altered drug clearance [9] [3] |

| Genetic Typing Platforms | Identification of pharmacogenetic variants | CYP2C19 genotyping for voriconazole metabolism prediction [3] |

| Protein Binding Assays | Determination of free drug fractions | Assessment of protein binding changes in hypoalbuminemia [9] [11] |

Experimental Protocol: Target Attainment Analysis

Protocol Title: Assessment of Pharmacodynamic Target Attainment for Anti-infective Regimens in Critically Ill Populations

Objective: To evaluate the probability of achieving pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic targets for [Anti-infective Agent] across different renal function subgroups and dosing regimens.

Methods:

- Population PK Model: Utilize previously developed population PK model for [Anti-infective Agent] with key covariates including estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and body size [4].

Monte Carlo Simulations:

- Generate virtual population (n=10,000) representing the target critically ill patient demographic

- Incorporate distributions for key covariates (renal function, body size, albumin)

- Simulate concentration-time profiles for standard and alternative dosing regimens

PD Target Definition:

Probability of Target Attainment (PTA) Calculation:

- Calculate PTA for each regimen across MIC distribution

- Determine cumulative fraction of response (CFR) for relevant pathogen populations

Output Analysis:

- Identify regimens achieving PTA >90% at relevant MIC values

- Recommend optimal dosing strategies for specific renal function subgroups

- Highlight patient populations at risk of subtherapeutic exposure

Case Applications and Clinical Translation

Exemplar Implementation: β-lactam Dosing Optimization

Recent research with piperacillin/tazobactam demonstrates the power of population PK approaches to identify suboptimal dosing in specific subpopulations. A 2025 study developed a population PK model in healthy adults to establish a baseline free from critical illness confounders, then performed Monte Carlo simulations across renal function subgroups [4]. The standard regimen (4g/0.5g q6h, 30-minute infusion) achieved a 90% probability of target attainment (PTA) for 50% fT>MIC at MIC values up to 4 mg/L in patients with normal renal function. However, this regimen frequently failed to achieve 90% PTA for more stringent targets (100% fT>MIC, 100% fT>4×MIC) or higher MICs, particularly in patients with augmented renal clearance (eGFR ≥130 mL/min) [4].

The precision dosing optimization workflow progresses from standard regimens through population PK analysis to targeted recommendations for at-risk subgroups.

Voriconazole Precision Dosing in Critically Ill Populations

Voriconazole exemplifies the challenges of antimicrobial dosing in critical illness, with its complex pharmacokinetics featuring significant interindividual variability, non-linear kinetics, and multiple influencing factors including inflammation and genetic polymorphisms [3]. A 2025 study of COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) patients developed a population PK model identifying voriconazole's apparent clearance (CL/F) at 3.17 L/h and volume of distribution (V/F) at 135 L for a standard patient [3]. Covariates significantly influencing clearance included continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), C-reactive protein (CRP), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, aspartate aminotransferase, and platelet count [3]. Monte Carlo simulations demonstrated that patients on CRRT required both higher loading doses and increased maintenance doses compared to those not on CRRT [3].

The integration of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) with model-informed precision dosing represents the most effective approach for addressing the extreme pharmacokinetic variability observed in critically ill patients [9]. Proactive TDM is recommended for vancomycin, teicoplanin, aminoglycosides, voriconazole, β-lactams, and linezolid in this population [9]. When combined with population PK models and Bayesian forecasting, TDM enables real-time dose individualization that accounts for each patient's unique and dynamic pathophysiology.

The imperative for precision dosing in critically ill patients stems from the profound alterations in antimicrobial pharmacokinetics that render standard dosing regimens inadequate. Population PK modeling provides the methodological foundation for understanding and predicting this variability, enabling the development of individualized dosing strategies that maximize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing toxicity. The integration of covariate data, therapeutic drug monitoring, and model-informed precision dosing represents the future standard for antimicrobial therapy in this vulnerable population. As drug development continues to address multidrug-resistant infections, these approaches will become increasingly essential for preserving the efficacy of new antimicrobial agents.

Critically ill patients present profound challenges for pharmacotherapy, particularly anti-infective dosing, due to extensive pathophysiological alterations that disrupt normal drug pharmacokinetics (PK). The complex interplay of haemodynamic, metabolic, and biochemical derangements significantly impacts drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) [15]. Understanding these changes is paramount for developing effective population pharmacokinetic (popPK) models and optimizing dosing strategies for anti-infectives. This application note details the key challenges and provides structured experimental protocols for investigating these phenomena within anti-infective dose optimization research.

The core challenge lies in the hyperdynamic and highly variable nature of critical illness. Pathophysiological changes include endothelial dysfunction causing capillary leak, fluid shifts from aggressive resuscitation, altered protein binding, and organ dysfunction that collectively modify drug disposition [15] [16]. Furthermore, therapies like renal replacement therapy (RRT) and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) add another layer of complexity, contributing to significant inter- and intra-patient variability [15]. This document synthesizes current evidence to provide a framework for quantifying these alterations and integrating them into robust popPK models.

Core Pathophysiological Changes and Their Impact on PK

Altered Volume of Distribution and Fluid Shifts

The volume of distribution (Vd) is significantly perturbed in critically ill patients, primarily due to fluid shifts and altered tissue perfusion. The systemic inflammatory response in conditions like sepsis leads to widespread endothelial damage, increased capillary permeability, and fluid extravasation into the interstitial space [17] [16]. Resuscitation with intravenous fluids, while necessary for hemodynamic support, exacerbates this by expanding the extracellular fluid compartment.

Impact on Drug Classes:

- Hydrophilic Drugs (e.g., beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, glycopeptides): These drugs primarily distribute in the vascular and extracellular fluid compartments. The expansion of this space leads to a marked increase in Vd, resulting in lower plasma concentrations and a high risk of subtherapeutic exposure if standard loading doses are administered [17] [16] [18]. For instance, the Vd of vancomycin is reported to double in critical illness, and a 3 mg/kg loading dose of aminoglycosides fails to achieve target peak levels in 50% of patients [16] [18].

- Lipophilic Drugs (e.g., fentanyl, propofol, midazolam): The impact is more complex. While the vascular compartment may be expanded, reduced peripheral perfusion in the early "rescue" phase of critical illness can impede distribution into deep tissue and adipose compartments, potentially leading to higher initial plasma concentrations [16].

Table 1: Impact of Critical Illness on Volume of Distribution for Select Anti-infectives

| Drug Class | Example Drugs | Physicochemical Property | Direction of Vd Change | Clinical Implication | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides | Gentamicin, Tobramycin | Hydrophilic | ↑ Increased by ~34% [18] | Standard 3 mg/kg load inadequate; consider 4-5 mg/kg [18] | [17] [16] [18] |

| Beta-lactams | Piperacillin, Meropenem | Hydrophilic | ↑ Significantly Increased | Subtherapeutic levels; increased loading dose required [15] [16] | [15] [16] [19] |

| Glycopeptides | Vancomycin | Hydrophilic | ↑ Can double [16] | Higher loading doses (e.g., 25-35 mg/kg) needed [16] | [15] [16] |

| Fluoroquinolones | Ciprofloxacin, Levofloxacin | Variable (Moderate lipophilicity) | ↑ Moderate Increase | Requires dose adjustment; TDM recommended [20] | [20] |

| Azoles | Voriconazole | Lipophilic | Variable (Influenced by protein binding) | Altered levels; TDM essential, especially with ECMO [20] | [20] |

Organ Dysfunction and Impact on Clearance

Organ dysfunction, particularly of the liver and kidneys, is a hallmark of critical illness and a major determinant of drug clearance.

Hepatic Dysfunction: Liver metabolism is compromised by reduced perfusion (shock, vasopressors) and direct cellular injury (hypoxic hepatitis, cholestasis) [15] [17]. The clearance of drugs is affected differently based on their extraction ratio (ER):

- High-ER Drugs (e.g., fentanyl, propofol): Clearance is blood flow-dependent. Reduced hepatic blood flow decreases clearance, increasing the risk of accumulation and toxicity [15] [17] [16].

- Low-ER Drugs (e.g., phenytoin, caspofungin): Clearance is dependent on enzyme function and protein binding. Systemic inflammation and cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) downregulate cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzyme activity, reducing metabolic clearance [15] [17] [21].

Renal Dysfunction and Augmented Renal Clearance (ARC):

- Acute Kidney Injury (AKI): Reduces the clearance of renally eliminated drugs (e.g., most beta-lactams, vancomycin, aminoglycosides), necessitating dose reduction to prevent toxicity [15].

- Augmented Renal Clearance (ARC): A hyperdynamic state in some critically ill patients (e.g., trauma, sepsis) leads to enhanced renal drug elimination, resulting in subtherapeutic concentrations if standard doses are used [22]. This is a key covariate in popPK models of beta-lactams [22].

Table 2: Impact of Organ Dysfunction and Inflammation on Drug Clearance Pathways

| Clearance Pathway | Pathophysiological Change | Impact on Drug PK | Example Drugs Affected | Key Inflammatory Biomarkers Linked to Change [21] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatic Metabolism (CYP450) | Cytokine-mediated downregulation of enzyme activity & cellular hypoxia | ↓ Reduced metabolic clearance of Low-ER drugs | Phenytoin, Voriconazole, Valproic Acid | IL-6, TNF-α, CRP |

| Hepatic Blood Flow | Reduced perfusion from shock, vasopressors, ventilation | ↓ Reduced clearance of High-ER drugs | Fentanyl, Propofol, Midazolam | - |

| Renal Elimination | Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) | ↓ Reduced renal clearance | Vancomycin, Piperacillin, Meropenem | CRP, Procalcitonin |

| Augmented Renal Clearance (ARC) | ↑ Increased renal clearance | Beta-lactams, Vancomycin [22] | - | |

| Organ Cross-Talk | Acute Kidney Injury reducing CYP450 activity (reno-hepatic crosstalk) | ↓ Reduced non-renal clearance | Multiple drugs metabolized by CYP450 [17] | IL-6, TNF-α |

Experimental Protocols for PopPK Model Development

Protocol for a PopPK Study of Beta-Lactams in Critically Ill Adults

1. Study Objective: To develop a popPK model for (e.g., meropenem) in critically ill patients, identifying and quantifying the impact of covariates like fluid balance, organ function, and inflammatory biomarkers on drug exposure.

2. Patient Population:

- Inclusion: Adults (≥18 years) admitted to the ICU receiving meropenem for proven or suspected infection.

- Exclusion: Known hypersensitivity; pregnancy.

- Stratification: Plan to enroll patients across a spectrum of renal function (including those on CRRT) and fluid balance states.

3. Blood Sampling Strategy:

- Employ sparse sampling designed for popPK analysis (e.g., 2-4 samples per patient per dosing interval at random time points).

- Collect samples pre-dose (trough), and at various time points post-infusion (e.g., 0.5h, 2h, 4h after the start of infusion).

- Align sampling with routine clinical blood draws where possible.

4. Data Collection (Covariates): Systematically collect the following potential covariates, as they are frequently tested and often significant in popPK models [22]:

- Patient Characteristics: Age, sex, actual body weight, ideal body weight, BMI.

- Physiological Parameters & Biomarkers: Serum creatinine, Albumin, C-Reactive Protein (CRP), Procalcitonin.

- Organ Function & Support: Estimated CLCR (e.g., Cockcroft-Gault), need for RRT/CRRT, SOFA score.

- Fluid Dynamics: Cumulative fluid balance (24-hour and total), use of vasopressors.

5. Bioanalysis: Quantify meropenem plasma concentrations using a validated method (e.g., LC-MS/MS or HPLC-UV).

6. Modelling Workflow:

- Use non-linear mixed-effects modelling (NONMEM or equivalent).

- Develop a base model (structural + statistical).

- Perform stepwise covariate model building to identify significant relationships (e.g., between CLCR and drug clearance, fluid balance and volume of distribution).

- Validate the final model internally and, if possible, with an external dataset [19].

Figure 1: Workflow for a Population Pharmacokinetic (PopPK) Study in Critically Ill Patients.

Protocol for Assessing the Impact of Inflammation on CYP450 Metabolism

1. Study Objective: To evaluate the correlation between longitudinal inflammatory biomarker levels and the metabolic clearance of a CYP450 probe drug in critically ill patients.

2. Study Design: Prospective, observational pharmacokinetic study.

3. Methodology:

- Probe Drug: Administer a microdose or a therapeutic dose of a specific CYP substrate (e.g., midazolam for CYP3A4 activity).

- PK Sampling: Collect serial blood samples over a dosing interval to characterize the clearance of the probe drug.

- Biomarker Analysis: Measure plasma concentrations of inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., CRP, IL-6, TNF-α) concurrently with PK sampling [21].

- Data Analysis: Use non-linear regression or popPK modelling to quantify the relationship between the level of each biomarker and the clearance of the probe drug.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for PopPK Research in Critical Care

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS System | Gold-standard for quantitative bioanalysis of drugs and metabolites in biological matrices. | Essential for measuring antibiotic plasma concentrations (e.g., meropenem, vancomycin) with high sensitivity and specificity. |

| CRP / IL-6 ELISA Kits | Quantification of inflammatory biomarkers to correlate with altered PK parameters. | Useful for investigating cytokine-mediated downregulation of CYP enzymes [21]. |

| NONMEM Software | Industry-standard for non-linear mixed-effects modelling of population PK/PD data. | Used for model development, covariate analysis, and simulation. |

| R or Python with PopPK Libraries | Open-source environment for data preparation, model diagnostics, and visualization. | Packages like 'nlmixr' (R) facilitate model evaluation and comparison. |

| Certified Bioanalytical Standards | Reference standards for drugs and internal standards for method development and validation. | Critical for ensuring the accuracy and reproducibility of concentration data. |

The pathophysiological triad of altered volume of distribution, profound fluid shifts, and evolving organ dysfunction creates a highly dynamic and unpredictable pharmacokinetic environment in critically ill patients. Success in anti-infective dose optimization research hinges on the systematic collection of high-quality PK data and the integration of clinically relevant covariates—such as fluid balance, renal function, and inflammatory biomarkers—into robust popPK models. The experimental protocols and frameworks outlined herein provide a foundation for generating evidence that can be translated into model-informed precision dosing strategies, ultimately improving therapeutic outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) modeling is a cornerstone of model-informed drug development (MIDD), enabling researchers to quantify and understand the sources of variability in drug exposure among individuals in a target population [13] [12]. For anti-infective drugs, which often possess narrow therapeutic windows and are used in diverse patient populations, this approach is particularly vital for optimizing dosing regimens to ensure both efficacy and safety [23] [24]. By integrating patient-specific covariates—such as age, weight, and organ function—PopPK models move beyond the "one dose fits all" paradigm toward personalized medicine, allowing for more informed dosing decisions in clinical practice [25]. The foundation of a PopPK analysis rests on three core model components: the structural model, the statistical model, and the covariate model. These components work in concert to describe the typical drug behavior in a population, quantify the random variability, and explain predictable sources of variability through patient characteristics [13] [1]. This article details these core components and provides practical protocols for their implementation in anti-infective dose optimization research.

Core Components of a PopPK Analysis

Structural Model

The structural model represents the theoretical, "platonic ideal" of how a drug is expected to behave in the body, describing the typical concentration-time course for a population [13] [1]. It is a mathematical representation of the pharmacokinetic (PK) processes of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) [13].

- Function and Purpose: The structural model acts as the scaffolding around which the observed data vary. Its primary purpose is to describe the central tendency of the PK data without accounting for variability between individuals [13] [26].

- Common Forms: The most prevalent structural models are mammillary compartmental models [1]. These models conceptualize the body as a series of compartments between which the drug flows.

- A one-compartment model describes the body as a single, homogenous unit and is suitable for drugs that distribute rapidly and evenly.

- Multi-compartment models (e.g., two or three compartments) are used when drug distribution occurs at different rates to various tissues. A central compartment (e.g., plasma and highly perfused organs) is typically connected to one or more peripheral compartments (e.g., less perfused tissues) [1].

- Key Parameters: The structural model is parameterized using fundamental PK parameters:

- Clearance (CL): The volume of plasma cleared of the drug per unit time, representing the body's efficiency in eliminating the drug [1].

- Volume of Distribution (V): The apparent volume in which a drug distributes in the body. Multi-compartment models will have a central volume (Vc or V1) and peripheral volume(s) (Vp or V2) [1].

- Inter-compartmental Clearance (Q): The flow rate of drug between the central and peripheral compartments in a multi-compartment model [27].

- Absorption Rate Constant (Ka): For extravascularly administered drugs (e.g., oral), this describes the rate of drug absorption into the systemic circulation [13].

Table 1: Common Structural Model Types and Their Applications in Anti-Infective PK

| Model Type | Description | Typical Use Case in Anti-Infectives |

|---|---|---|

| One-Compartment | Single, homogeneous unit with first-order elimination. | Drugs with simple, rapid distribution; initial model screening. |

| Two-Compartment | A central compartment (e.g., plasma) and one peripheral tissue compartment. | Most common model for drugs showing bi-phasic decline (e.g., Vancomycin [28]). |

| Three-Compartment | A central compartment with two peripheral compartments with different distribution rates. | Drugs with complex, multi-phasic distribution (e.g., some antibiotics in critically ill patients). |

| Transit Compartment | A series of compartments to model delayed absorption. | Drugs with complex absorption phases (e.g., Rifampicin [23]). |

Statistical Model

The statistical model quantifies the random variability that is not explained by the structural model alone. It accounts for the "noise" in the data and the differences between individuals [13] [1]. This component is essential because it formally recognizes that individuals in a population are not identical to the "typical" patient.

- Function and Purpose: To characterize and partition the different sources of random variability in the observed data, including differences between subjects, between occasions, and measurement error [13] [26].

- Types of Variability:

- Between-Subject Variability (BSV): Also known as Inter-individual Variability (IIV), this is the variability of a PK parameter (e.g., CL, V) between different individuals in the population. It is modeled by assuming that an individual's parameter value (Pᵢ) deviates from the typical population value (Pₚₒₚ) by a random effect (ηᵢ). This is typically assumed to follow a log-normal distribution to prevent physiologically impossible negative parameter values [13] [26]. The magnitude of BSV is often reported as a variance or coefficient of variation.

- Example:

CLᵢ = TVCL × exp(ηᵢ^CL), where ηᵢ^CL ~ N(0, ω²)

- Example:

- Between-Occasion Variability (BOV): This accounts for variability within the same individual when the drug is administered on different occasions (e.g., different cycles of therapy) [13].

- Residual Unexplained Variability (RUV): Also known as the residual error, this captures the discrepancy between an individual's model-predicted concentration and their actual observed concentration. This variability arises from assay error, model misspecification, timing inaccuracies, and within-subject fluctuations [13] [26]. Common statistical models for RUV include proportional, additive, or combined error structures.

- Between-Subject Variability (BSV): Also known as Inter-individual Variability (IIV), this is the variability of a PK parameter (e.g., CL, V) between different individuals in the population. It is modeled by assuming that an individual's parameter value (Pᵢ) deviates from the typical population value (Pₚₒₚ) by a random effect (ηᵢ). This is typically assumed to follow a log-normal distribution to prevent physiologically impossible negative parameter values [13] [26]. The magnitude of BSV is often reported as a variance or coefficient of variation.

Table 2: Components of the Statistical Model in PopPK

| Component | Symbol | Description | Common Model Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Between-Subject Variability (BSV) | η (eta) | Random deviation of an individual's parameter from the population typical value. | Log-normal: Pᵢ = Pₚₒₚ × exp(ηᵢ) |

| Residual Unexplained Variability (RUV) | ε (epsilon) | Random difference between an individual's predicted and observed concentration. | Additive: Cₒᵦₛ = Cₚᵣₑ𝒹 + ε Proportional: Cₒᵦₛ = Cₚᵣₑ𝒹 × (1 + ε) Combined: Cₒᵦₛ = Cₚᵣₑ𝒹 × (1 + ε₁) + ε₂ |

Covariate Model

While the statistical model quantifies random variability, the covariate model aims to explain a portion of the BSV by identifying patient-specific characteristics (covariates) that have a systematic, predictable influence on PK parameters [13] [25].

- Function and Purpose: To establish quantitative relationships between clinically relevant patient factors and PK parameters, thereby reducing the unexplained BSV and enabling more precise, individualized dosing [13] [26].

- Common Covariates in Anti-Infective Research:

- Demographic: Body size (weight, fat-free mass), age (including postmenstrual age in pediatrics), sex [13] [23].

- Organ Function: Creatinine clearance (CRCL) or serum creatinine for renal function; liver enzyme levels or bilirubin for hepatic function [24] [27].

- Clinical Status: Serum albumin levels, disease status (e.g., HIV, diabetes), APACHE-II score in critically ill patients [23] [27].

- Genetic Factors: Polymorphisms in drug transporter genes (e.g., SLCO1B1 for Rifampicin) or metabolizing enzymes [23].

- Modeling Relationships: Covariates are incorporated into the model using mathematical functions. For example, the effect of body weight on clearance is often modeled using a power function:

CLᵢ = TVCL × (Weightᵢ / 70)^θᶜᴸ × exp(ηᵢ^CL)where TVCL is the typical clearance for a 70 kg individual, and θᶜᴸ is the estimated exponent describing the strength of the relationship.

Table 3: Examples of Covariate Effects on Anti-Infective PK Parameters

| Drug | Covariate | Effect on PK Parameter | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampicin [23] | Fat-free mass (FFM) | Increases Clearance (CL) | Dosing based on FFM may be more rational than total body weight. |

| Polymyxin B [27] | Albumin (ALB) Level | Explains variability in CL | Critically ill patients with low ALB may have altered clearance. |

| Polymyxin B [27] | Age | Explains variability in Volume of Distribution (Vd) | Older patients may have a different volume of distribution. |

| Vancomycin [28] | Creatinine Clearance (CLcr) | Primary determinant of CL | Dosing must be adjusted based on renal function. |

| Colistin [24] | Renal Function | Significantly impacts CL | Dosing optimization required in lung transplant recipients. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integration of these three core components in a typical PopPK model development process.

PopPK Model Development Workflow

Experimental Protocols for PopPK Model Development

Protocol for Structural Model Development

Objective: To identify the compartmental model that best describes the typical concentration-time profile of the anti-infective drug in the population.

- Data Preparation: Assemble a dataset containing all drug concentration measurements and corresponding sampling times. For drugs administered extravascularly (e.g., orally), include the dose and dosing time [1].

- Exploratory Data Analysis: Create semi-logarithmic plots of concentration versus time for all individuals. Visually inspect the plots to identify the number of distinct exponential phases in the concentration decline, which provides an initial indication of the required number of compartments [1].

- Base Model Building:

- Start by fitting a one-compartment model with first-order elimination.

- Progress to more complex models (e.g., two-compartment, three-compartment) if the data support the additional complexity.

- For oral drugs, test different absorption models: first-order, zero-order, or transit compartment models to handle complex absorption patterns, as was beneficial for Rifampicin [23].

- Model Comparison: Compare competing structural models using objective function value (OFV), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). A decrease in OFV of >3.84 (p<0.05, χ² distribution, 1 degree of freedom) for a nested model, or a lower AIC/BIC, suggests a significantly better fit [1]. Additionally, use goodness-of-fit plots to assess model performance visually.

Protocol for Covariate Model Building

Objective: To systematically identify and validate patient covariates that significantly explain the between-subject variability in key PK parameters.

- Covariate Selection: Based on physiological knowledge of the drug's disposition (ADME) and the patient population, compile a list of potential covariates. Common candidates for anti-infectives include weight, age, creatinine clearance, and albumin levels [13] [27].

- Stepwise Covariate Modeling (SCM):

- Forward Inclusion: Add each pre-specified covariate to the base model one at a time. Use the Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT), where a reduction in OFV > 3.84 (p<0.05) for 1 degree of freedom, indicates a significant improvement in the model fit. Retain all covariates that meet the significance criterion.

- Backward Elimination: Create a full model containing all covariates identified in the forward inclusion step. Then, remove each covariate from the full model one by one. A covariate is retained in the final model only if its removal causes a statistically significant increase in OFV (e.g., >6.63 for p<0.01, 1 df), ensuring only the most influential covariates are included [13].

- Model Evaluation: After identifying the final covariate model, perform a thorough evaluation. This includes:

- Goodness-of-Fit Plots: Observed vs. Population Predicted Concentrations; Observed vs. Individual Predicted Concentrations; Conditional Weighted Residuals vs. Time/Predictions.

- Visual Predictive Check (VPC): Simulating multiple datasets using the final model and comparing the simulated percentiles with the observed data to assess the model's predictive performance [23] [28].

- Bootstrap Analysis: Performing a non-parametric bootstrap to evaluate the stability and precision of the final parameter estimates [29].

Protocol for Model Validation and Dosing Simulation

Objective: To validate the final PopPK model and utilize it for clinical dosing optimization via Monte Carlo simulations.

- Model Validation:

- Internal Validation: Use techniques like bootstrap (as mentioned above) and data-splitting, where the model is developed on a training set and tested on a validation set [25].

- External Validation: If possible, test the model's predictive performance on a completely new, independent dataset from a different study or clinical center [23]. This is the strongest form of validation.

- Monte Carlo Simulation:

- Define the target patient population and their covariate distributions (e.g., range of weights, renal function) [23] [27].

- Using the final PopPK model (parameter estimates and their variances), simulate concentration-time profiles for a large number of virtual patients (e.g., 1000-5000) for a given dosing regimen [23] [27].

- Target Attainment Analysis:

- For anti-infectives, define a PK/PD target associated with efficacy. Common targets include the ratio of the area under the concentration-time curve to the minimum inhibitory concentration (AUC/MIC) or the time that free drug concentration remains above the MIC (fT>MIC) [27].

- Calculate the Probability of Target Attainment (PTA) as the proportion of virtual patients who achieve the predefined PK/PD target for a given dosing regimen.

- Repeat the simulation for multiple dosing regimens (e.g., different doses, intervals) to identify the regimen that achieves the desired PTA (e.g., ≥90%) in the target population [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PopPK Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in PopPK Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Modeling Software | NONMEM, Monolix, Pmetrics (for R), Phoenix NLME | Industry-standard software for performing nonlinear mixed-effects modeling and parameter estimation [26] [27]. |

| Programming Languages | R, Python | Used for data preparation, visualization, simulation, and result analysis. R is particularly dominant in pharmacometrics. |

| Statistical Packages | mrgsolve (R package), xpose (R package) |

mrgsolve is used for simulating from PK/PD models; xpose is used for diagnostics and model evaluation [23]. |

| Bioanalytical Assays | LC-MS/MS | The gold standard for precise and accurate quantification of drug and metabolite concentrations in biological matrices (e.g., plasma) [27]. |

| Simulation Tools | Built-in simulators in Monolix/NONMEM, mrgsolve, Shiny applications |

Used for performing Monte Carlo simulations and creating user-friendly interfaces for model-based dosing [23]. |

Population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) analysis is a critical component of modern model-informed drug development (MIDD), enabling researchers to quantify and explain the variability in drug exposure among individuals from a target patient population. Regulatory agencies worldwide, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), recognize PopPK as a powerful tool for guiding drug development decisions and informing therapeutic individualization through tailored dosing strategies [30]. By integrating drug, disease, and trial information, PopPK analyses help support more efficient drug development and regulatory decisions, particularly for anti-infective agents where appropriate dosing is crucial for clinical efficacy and preventing resistance [31] [32].

The FDA's Division of Pharmacometrics (DPM) has established PopPK analyses as fundamental to its regulatory review process, with a strategic focus on improving drug dosing decisions for all patients [31]. Similarly, the EMA provides specific guidelines on reporting PopPK results to ensure sufficient detail for regulatory assessment [33]. The integration of PopPK analyses in marketing applications has in some cases alleviated the need for postmarketing requirements or commitments, accelerating patient access to novel therapies [30].

Regulatory Framework and Guidelines

FDA Guidance on Population Pharmacokinetics

The FDA's guidance document "Population Pharmacokinetics" represents the agency's current thinking on the application of PopPK analysis in drug development. Issued in February 2022 as a Level 1 guidance, this document assists sponsors and applicants of new drug applications (NDAs), biologics license applications (BLAs), abbreviated new drug applications (ANDAs), and investigational new drugs (IND) applications [30]. The guidance emphasizes the importance of PopPK analysis in guiding drug development and informing recommendations on therapeutic individualization, particularly through tailored dosing regimens [30].

The FDA's structured approach to PopPK review is managed through the Division of Pharmacometrics, which employs a multidisciplinary team including quantitative clinical pharmacologists, statisticians, engineers, and data management experts [31]. This division has developed standardized formats for PopPK reports to facilitate regulatory review and has made the integration of quantitative clinical pharmacology summaries a standard practice in NDA/BLA submissions [31]. The FDA also actively supports international harmonization of pharmacometrics standards through quarterly cluster meetings with global regulatory agencies and participation in ICH guidance development [31].

EMA Guidelines and Reporting Standards

The European Medicines Agency provides complementary guidance on how to present PopPK analysis results to enable secondary evaluation by regulatory authorities [33]. The EMA emphasizes that reporting should provide sufficient detail to allow assessment of the conducted analysis and conclusions drawn, with a focus on transparent methodology and results interpretation [33]. The EMA's scientific guidelines on clinical pharmacology and pharmacokinetics help medicine developers prepare marketing authorization applications for human medicines, establishing a comprehensive framework for PopPK integration in drug development [34].

Recently, the EMA has been preparing to release draft guidance on mechanistic models in Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD), including PopPK models, with a concept paper released for public consultation from February to May 2025 [35]. This initiative aims to encourage wider use of these models and promote a standardized approach to their application in drug development [35].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of FDA and EMA PopPK Regulatory Guidance

| Aspect | FDA Approach | EMA Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Guidance Document | Population Pharmacokinetics Guidance for Industry (February 2022) [30] | Reporting the results of population pharmacokinetic analyses [33] |

| Regulatory Scope | NDAs, BLAs, ANDAs, IND applications [30] | Marketing Authorization Applications for human medicines [34] |

| Key Emphasis | Therapeutic individualization through tailored dosing [30] | Transparency and secondary evaluability of analyses [33] |

| Review Structure | Division of Pharmacometrics [31] | Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) |

| Recent Developments | Standardized templates for PopPK reviews [31] | Draft guidance on mechanistic models in MIDD (2025) [35] |

PopPK Applications in Anti-infective Drug Development

Case Study: Aztreonam-Avibactam Dose Optimization

A recent application of PopPK in anti-infective development illustrates its critical role in dose optimization and regimen selection. A 2024 population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling study aimed to optimize aztreonam-avibactam dose regimens for adult patients [5]. The researchers developed a simultaneous aztreonam and avibactam PopPK model using pharmacokinetic data from two phase 3 trials, creating a two-compartment model with zero-order infusion and first-order elimination [5].

The final model incorporated 4,914 aztreonam plasma samples from 431 subjects and 18,222 avibactam plasma samples from 2,635 subjects, identifying time-varying creatinine clearance as a key covariate on clearance for both drugs [5]. Infection type also significantly influenced clearance and volume, with the lowest exposures observed in patients with complicated intra-abdominal infections (cIAI) [5]. The PopPK analysis demonstrated that the final aztreonam-avibactam dose regimens achieved joint pharmacodynamic target attainment (PTA) of 89% to >99% at steady state across renal function groups, while ceftazidime-avibactam plus aztreonam regimens proposed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America achieved joint PTA below 85% due to insufficient avibactam exposures [5].

Case Study: Teicoplanin Dosing Optimization

Another compelling example comes from a 2022 study that developed a PopPK model for unbound teicoplanin in Chinese adult patients [36]. This research highlights the importance of PopPK in optimizing dosing regimens for anti-infective agents with complex pharmacokinetic properties. The study collected 103 unbound teicoplanin concentrations from 72 patients and established a one-compartment pharmacokinetic model with first-order elimination [36].

The analysis identified that clearance and volume of distribution of unbound teicoplanin were positively correlated with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and serum albumin concentrations, respectively [36]. Dosing simulation results demonstrated that standard dosing regimens failed to meet the treatment needs of all patients, requiring optimization based on eGFR and serum albumin concentrations [36]. The study found that high eGFR and serum albumin concentration were associated with reduced probability of achieving target unbound trough concentrations, providing critical insights for personalized teicoplanin therapy [36].

Table 2: Key Covariates Identified in Anti-infective PopPK Case Studies

| Drug | Population | Key Covariates | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aztreonam-Avibactam [5] | Adult patients with various infections | Time-varying creatinine clearance, infection type | Dosing optimization across renal function groups and infection types |

| Teicoplanin (unbound) [36] | Chinese adult patients | eGFR, serum albumin concentrations | Personalized dosing based on renal function and protein binding status |

| Aztreonam-Avibactam [5] | Patients with cIAI | Infection type (cIAI) | Identified subpopulation requiring special consideration for exposure targets |

Experimental Protocols for PopPK Analysis

PopPK Model Development Workflow

The standard methodology for developing PopPK models follows a structured workflow that integrates data collection, model development, validation, and simulation. The following diagram illustrates this process:

Protocol for PopPK Analysis in Anti-infective Development

1. Data Collection and Preparation

- Collect rich or sparse pharmacokinetic samples from clinical trials, ensuring appropriate timing relative to dosing [36]

- Record demographic data (age, weight, sex), physiological parameters (serum creatinine, albumin), and clinical laboratory values [36]

- Document precise dosing information (dose, frequency, infusion duration) and sampling times [36]

- For anti-infective agents, record pathogen susceptibility and infection site details [5]

2. Analytical Method Validation

- Employ validated bioanalytical methods (e.g., UPLC-MS/MS) for drug concentration measurement [36]

- For highly protein-bound drugs, implement ultrafiltration methods to determine unbound concentrations [36]

- Establish calibration curves and validate precision, accuracy, and recovery rates according to regulatory standards [36]

3. Model Development

- Utilize specialized software (e.g., NONMEM, R) for nonlinear mixed-effects modeling [36]

- Test structural models (one-compartment, two-compartment) to describe drug disposition [32]

- Implement statistical models to account for interindividual variability, interoccasion variability, and residual unexplained variability [32]

- Incorporate covariate relationships using forward addition/backward elimination procedures [5] [36]

4. Model Validation

- Apply goodness-of-fit plots to assess model performance [32]

- Conduct visual predictive checks to evaluate model predictive performance [32]

- Perform bootstrap analysis to assess parameter uncertainty and model stability [32]

- When applicable, use external validation with independent datasets [32]

5. Model Application and Simulation

- Execute Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate probability of target attainment for various dosing regimens [5] [36]

- Simulate drug exposure metrics under different clinical scenarios (various renal functions, albumin levels) [36]

- Identify optimal dosing strategies to maximize efficacy while minimizing toxicity [5]

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for PopPK Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| NONMEM Software [36] | Nonlinear mixed-effects modeling platform | Primary software for PopPK model development and parameter estimation |

| R Statistical Environment [36] | Data assembly, exploratory analysis, and visualization | Data preprocessing, model diagnostics, and graphical presentation of results |

| UPLC-MS/MS System [36] | High-sensitivity drug concentration measurement | Quantification of drug concentrations in biological matrices |

| Centrifree Ultrafiltration Device [36] | Separation of unbound drug fraction | Determination of pharmacologically active unbound drug concentrations |

| Wings for NONMEM [36] | NONMEM execution and assistance | Streamlining model execution and output management |

| Clinical Data Standards [30] [33] | Regulatory-compliant data collection | Ensuring data quality and integrity for regulatory submissions |

Covariate Analysis in PopPK Modeling

The identification of clinically relevant covariates is essential for understanding sources of pharmacokinetic variability. The relationship between key covariates and PopPK parameters can be visualized as follows:

Population pharmacokinetic modeling represents a cornerstone of modern anti-infective drug development, providing a robust framework for understanding drug behavior in target patient populations. The regulatory frameworks established by the FDA and EMA emphasize the importance of PopPK analyses in supporting dosing recommendations and therapeutic individualization [30] [33]. As demonstrated by the case studies on aztreonam-avibactam and teicoplanin, PopPK approaches enable model-informed dose optimization that accounts for patient-specific factors such as renal function, serum albumin levels, and infection characteristics [5] [36].

The continued evolution of regulatory guidelines, including the EMA's upcoming guidance on mechanistic models [35] and the FDA's ongoing refinement of PopPK review standards [31], ensures that PopPK methodologies will remain essential tools for advancing anti-infective therapy. By implementing the experimental protocols and utilizing the research tools outlined in this document, scientists and drug development professionals can generate high-quality PopPK data to support regulatory submissions and optimize anti-infective dosing strategies for diverse patient populations.

Building and Applying PopPK Models: From Data to Clinical Decision-Making

In population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) modeling for anti-infective dose optimization, the quality of analytical outcomes is fundamentally dependent on rigorous data preparation. Critical issues including sparse sampling, outlier observations, and data below the quantification limit present significant analytical challenges that can substantially influence model development and subsequent dosing recommendations. This application note provides structured protocols and evidence-based solutions for addressing these pervasive data challenges, with specific emphasis on applications within antimicrobial pharmacometrics. The systematic approaches outlined herein enable researchers to transform complex, real-world data into reliable analytical datasets for robust population modeling and precision dosing strategies.

Handling Sparse Data in Pharmacokinetic Studies

Background and Challenges

Sparse sampling designs, where only a limited number of blood samples are collected per subject, are frequently necessary in clinical settings where intensive sampling is impractical, such as in critically ill patients, pediatric populations, or outpatient studies. Traditional pharmacokinetic analysis methods like standard two-stage (STS) approaches often fail to provide reliable parameter estimates from sparse data, potentially leading to biased results and suboptimal dosing recommendations [37].

Evidence-Based Protocol for Sparse Data Analysis

Protocol Title: Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling of Sparse Data Using Non-Parametric Adaptive Grid Algorithm

Experimental Validation: A post-hoc analysis of morphine pharmacokinetics demonstrated that sparse sampling with as few as three samples per subject could accurately characterize a complex 3-compartment model when analyzed with appropriate population methods [37]. The study compared traditional STS modeling with nonparametric adaptive grid (NPAG) population modeling in 14 healthy volunteers, with validation in 5 surgical patients.

Key Experimental Findings on Sparse Data Sufficiency:

Table 1: Predictive Performance of Sparse vs. Intensive Sampling for Morphine PK

| Sampling Strategy | Analysis Method | Mean Error (ME) | Root-Mean-Square Error | Model Structure Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 samples/subject | NPAG | 0.76 ng/mL | 25.8 ng/mL | 3-compartment |

| 3 samples/subject | NPAG | -1.0 ng/mL | 26.2 ng/mL | 3-compartment |

| Intensive sampling | STS | 4.43 ng/mL | Not reported | Inaccurate |

Methodological Workflow:

- Study Design Phase: Implement optimal sampling theory principles to identify informative time points for sparse sampling

- Data Collection: Collect a minimum of 3 strategically timed samples per subject based on optimal design calculations

- Model Development: Utilize NPAG or other nonlinear mixed-effects modeling software capable of handling sparse data

- Model Validation: Apply bootstrap methods and prediction-corrected visual predictive checks to evaluate model performance

- Dosing Optimization: Use final model parameters to simulate exposure profiles and optimize dosing regimens

Critical Considerations: The successful application of sparse sampling methodologies requires careful structural model identification from more intensively sampled pilot data before implementation in sparse sampling designs [37] [38].

Outlier Detection and Analysis in Clinical Datasets

Theoretical Framework for Outlier Characterization

Outliers in clinical and pharmacokinetic data can be systematically classified by three primary attributes: root cause, type, and measure. Proper characterization is essential for determining appropriate handling strategies [39].

Table 2: Classification Framework for Outliers in Pharmacometric Data

| Characteristic | Category | Description | Clinical Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root Cause | Error-based | Human or instrument errors | Entry of additional digit in weight field in electronic record |

| Fault-based | Underlying system breakdown | Congestive heart failure causing symptoms | |

| Natural deviation | Chance-based extreme values | Extremely tall individual with no pathology | |

| Novelty-based | New generative mechanism | Unexpected drug effect for unrelated indication | |

| Type | Point | Single anomalous observation | Patient with disease relative to healthy population |

| Collective | Cluster of related anomalies | Rare infectious disease cluster in geographic area | |

| Contextual | Abnormal in specific context | Pregnancy changes abnormal in general population but normal in pregnancy context | |

| Measure | Distance-based | Degree of deviation from expected | Systolic blood pressure relative to hypertension threshold |

| Probability-based | Statistical rarity of observation | Rare adverse event during therapeutic management | |

| Information-based | Novel patterns not in traditional descriptions | Novel signs/symptoms not part of traditional disease description |

Augmented Intelligence Protocol for Outlier Analysis

Protocol Title: Five-Step Augmented Intelligence Framework for Clinical Discovery Through Outlier Analysis

Methodology Overview: This protocol reframes clinical discovery as an outlier detection problem within a structured augmented intelligence framework, enabling systematic identification of novel observations that may lead to scientific breakthroughs [39].

Experimental Workflow:

Implementation Details:

- Define Patient Population: Establish clear inclusion criteria and clinical outcomes of interest for the target population

- Build Predictive Model: Develop multivariate models predicting expected outcomes using available clinical covariates

- Identify Outliers: Calculate inconsistency scores expressing deviation between model predictions and actual observations

- Expert Investigation: Subject matter experts review identified outliers to distinguish meaningful anomalies from noise

- Hypothesis Generation: Formulate testable scientific hypotheses based on investigated outliers

Application Note: This approach is particularly valuable in antimicrobial resistance research, where outlier patients with unexpected treatment responses may reveal novel resistance mechanisms or therapeutic opportunities [39] [40].

High-Throughput Screening Outlier Mining

Protocol Adaptation for Pharmaceutical Screening: In high-throughput screening for anti-infective compounds, outlier mining techniques enable identification of false negatives and structure-activity relationship (SAR) borderline compounds that may contribute substantially to robust SAR understanding [41].

Technical Implementation:

- Utilize one- and two-dimensional molecular descriptors to encode structural information

- Apply logistic regression to calculate hit/nonhit probability scores

- Compute inconsistency scores to identify outliers for validation experiments

- Prioritize false-negative outliers and SAR-compliant borderline compounds for follow-up

Management of Below Lower Limit of Quantification (BLQ) Data

Analytical and Clinical Significance of BLQ Values

BLQ data points occur when analyte concentrations fall below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of bioanalytical methods. Traditional approaches that simply exclude these values can introduce significant bias in pharmacokinetic parameter estimation, particularly for drugs with complex elimination profiles or when characterizing terminal elimination phases [42].