Pharmacometric Modeling and Simulation: Revolutionizing Anti-Infective Drug Development and Precision Dosing

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role pharmacometric modeling and simulation (M&S) plays in the development and optimization of anti-infective therapies.

Pharmacometric Modeling and Simulation: Revolutionizing Anti-Infective Drug Development and Precision Dosing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role pharmacometric modeling and simulation (M&S) plays in the development and optimization of anti-infective therapies. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling, its methodological applications in designing effective dosage regimens against resistant pathogens, and its utility in troubleshooting therapy failures and optimizing treatment for special populations. Further, the article examines the validation of these models and their growing acceptance by regulatory agencies, highlighting how this quantitative discipline accelerates timelines, reduces development costs, and paves the way for more personalized and effective antimicrobial pharmacotherapy.

The Essential Primer: Core Principles of Pharmacometrics in Anti-Infective Therapy

Pharmacometrics represents a critical, quantitative discipline in modern drug development, integrating pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics (PD), and disease biology to inform decision-making. It employs mathematical models to characterize and predict the time-course of drug effects, accounting for variability in patient populations [1] [2]. Within anti-infective development, these model-informed approaches are transformative, enabling optimized dosing regimens for vulnerable populations, overcoming clinical trial recruitment challenges, and supporting regulatory strategies for accelerated approval [1] [3]. This article details core pharmacometric components and provides applicable protocols for integrating these methods into anti-infective research pipelines.

Pharmacometrics is defined as a science focused on developing and applying mathematical and statistical methods to characterize, understand, and predict the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic behavior of drugs [2]. It serves as a quantitative framework that bridges diverse data sources—from pre-clinical studies, clinical trials, and real-world evidence—to translate drug and disease knowledge into actionable development strategies [3]. In the context of anti-infective therapeutics, pharmacometrics is indispensable for tackling the unique challenges of rapid pathogen evolution, narrow therapeutic windows, and the need for combination therapies to prevent resistance. By integrating models of disease progression, host-pathogen interactions, and drug effects, pharmacometrics provides a powerful toolkit for designing more efficient and informative clinical trials and for tailoring treatments to specific patient subpopulations [2].

Core Components of Pharmacometrics

The practice of pharmacometrics is built upon several interconnected modeling approaches. The table below summarizes the key model types, their definitions, and primary applications in anti-infective development.

Table 1: Core Pharmacometric Modeling Approaches in Anti-Infective Development

| Model Type | Definition | Primary Application in Anti-Infectives |

|---|---|---|

| Population PK (PopPK) [1] | Uses nonlinear mixed-effects models to analyze PK data from all individuals in a study population, quantifying between-subject variability (BSV). | Characterizing drug exposure variability in patients with differing organ function, ages, or disease states to identify covariates for dose adjustment. |

| Physiologically-Based PK (PBPK) [1] [2] | Mechanistic model incorporating physiological, genetic, and biochemical parameters to simulate a drug's ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion). | Predicting drug-drug interaction potential in complex HAART regimens; extrapolating PK from adults to pediatric populations. |

| PK/PD Modeling [2] | Mathematical relationship linking PK (drug concentration) to PD (pharmacological effect), often using an indirect-response or Emax model. | Quantifying the exposure-response relationship for efficacy (e.g., microbial kill) and safety (e.g., QT prolongation) to establish a therapeutic window. |

| Disease Progression (DisP) Modeling [2] | A model that mathematically characterizes the natural time-course of a disease and how a therapeutic intervention alters that trajectory. | Modeling bacterial load dynamics or viral replication in untreated patients and the modifying effect of antimicrobial agents. |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) [2] | A highly mechanistic framework integrating drug action with systems-level disease biology, often involving multiple interconnected pathways. | Simulating the emergence of antimicrobial resistance and evaluating the efficacy of novel combination therapies to suppress resistant subpopulations. |

| Model-Based Meta-Analysis (MBMA) [2] | A quantitative analysis that integrates and compares data from multiple clinical studies to understand the competitive landscape and drug class effects. | Informing dose selection and trial endpoints by analyzing historical data on standard-of-care anti-infectives. |

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful pharmacometric analysis relies on a combination of high-quality data and sophisticated software. The following table details the essential "toolkit" for researchers in this field.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Key Resources for Pharmacometric Analysis

| Category / Item | Function and Description |

|---|---|

| Clinical Data | |

| Richly-Sampled PK/PD Data | Provides the foundational data for building and validating PK, PD, and PK/PD models. Crucial for characterizing time-dependent processes. |

| Sparse PopPK Data from Clinical Trials | Used for population analysis to quantify variability and identify patient factors (covariates) influencing drug exposure and response. |

| Biomarker Data (e.g., Viral Load, Bacterial Counts) | Serves as a quantitative PD endpoint for modeling drug effect on the pathogen and disease progression. |

| Software & Computational Tools | |

| NONMEM (Nonlinear Mixed Effects Modeling) | The industry-standard software for population PK/PD analysis using nonlinear mixed-effects models. |

| R or Python | Open-source programming languages used for data preparation, exploratory analysis, model diagnostics, and visualization (e.g., using the xpose and ggplot2 packages in R) [4]. |

| PBPK Software (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp) | Specialized platforms containing physiological and demographic libraries to develop and simulate PBPK models. |

| Graphviz (DOT language) | An open-source graph visualization tool used to create clear diagrams of model structures, workflows, and biological pathways, as utilized in this document. |

Experimental Protocol for an Integrated PopPK/PD Analysis

This protocol outlines a standardized workflow for conducting a population PK/PD analysis to support anti-infective development.

Objective: To develop a PopPK model for a novel anti-infective drug, followed by a PD model linking drug exposure to a biomarker of efficacy (e.g., viral load), and to perform clinical trial simulations to evaluate proposed dosing regimens.

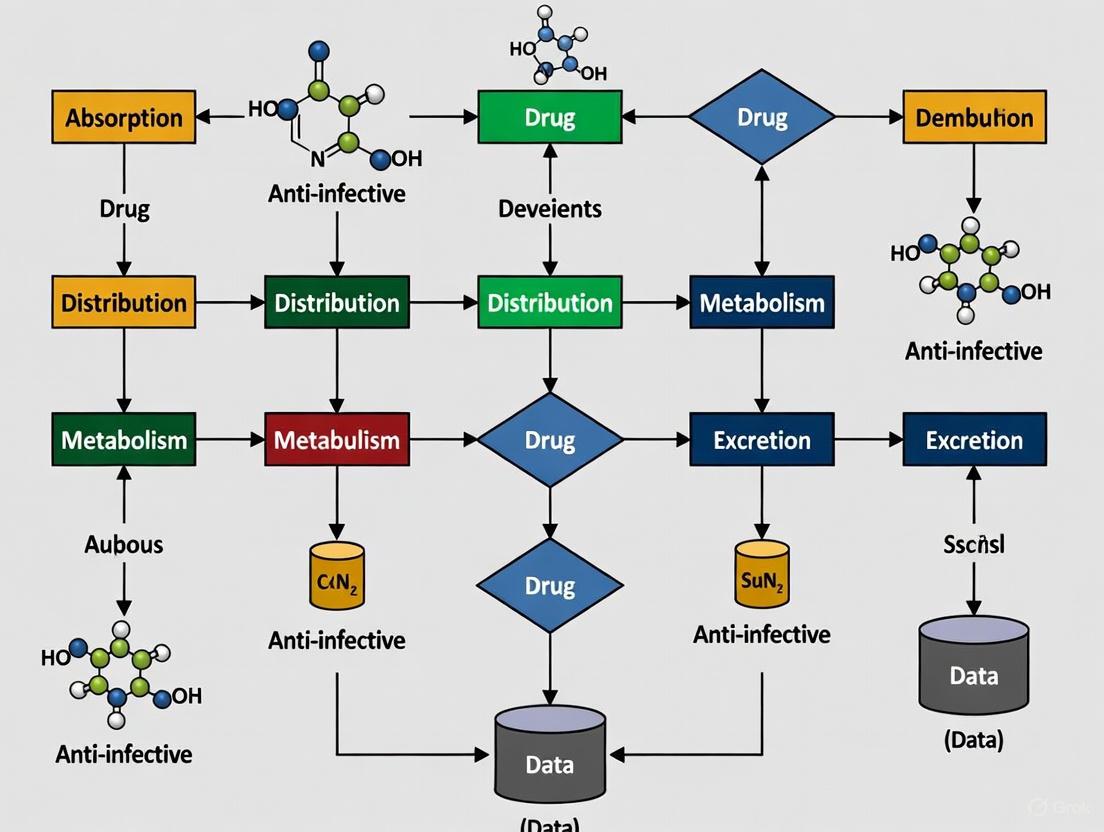

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the integrated, iterative nature of a pharmacometric analysis.

Stepwise Detailed Protocol

Step 1: Planning and Regulatory Interaction (Stage 1 of MIDD)

- Action: Define the Question of Interest (QOI) and Context of Use (COU). Document the planned analysis in a Model Analysis Plan (MAP) [1].

- Example QOI: "What is the influence of renal impairment on drug exposure, and what dose adjustment is recommended for patients with severe renal impairment?"

- Documentation: The MAP should include sections on Introduction, Objectives, Data Sources, and planned Methods for model development and evaluation.

Step 2: Data Assembly and Exploratory Analysis

- Action: Collate all PK/PD data, dosing records, and patient covariates from clinical trials. Perform data cleaning and exploratory graphical analysis (e.g., concentration-time profiles, empirical Bayesian estimates vs. covariates) [4].

- Software: R or Python for data preparation and visualization.

- Key Outputs: A consolidated dataset suitable for nonlinear mixed-effects modeling and initial hypotheses on covariate relationships.

Step 3: Base Population PK Model Development

- Action: Develop a structural PK model (e.g., 1-, 2-, or 3-compartment) using nonlinear mixed-effects modeling. Estimate between-subject variability (BSV) on key parameters (e.g., Clearance - CL, Volume - V) and characterize residual error.

- Software: NONMEM, Monolix, or equivalent.

- Model Selection: Use diagnostic plots and statistical criteria (e.g., drop in objective function value - OFV) to select the best structural model.

Step 4: Covariate Model Building

- Action: Identify patient-specific factors (e.g., weight, renal function, age) that explain a portion of the BSV. Use a stepwise forward addition/backward elimination procedure.

- Technical Criteria: A drop in OFV of >3.84 (p<0.05, χ², 1 df) for forward inclusion and >6.63 (p<0.01) for backward deletion.

- Output: A final PopPK model that can simulate drug exposure for virtual patients with different demographic and pathophysiological characteristics.

Step 5: PK/PD Model Development

- Action: Link the final PopPK model to a PD endpoint. For anti-infectives, this often involves an indirect-response model or a direct-effect model to characterize the drug's effect on pathogen load.

- Common Models:

- Direct Effect Emax Model:

Effect = E0 - (Emax * C) / (EC50 + C) - Indirect Response Model (Inhibition of Growth):

dR/dt = Kin * (1 - (Imax * C)/(IC50 + C)) - Kout * R - Viral Dynamics Model: A system of differential equations modeling target cells, infected cells, and virus.

- Direct Effect Emax Model:

- Objective: Quantify the exposure-response relationship and identify a target exposure for efficacy.

Step 6: Model Evaluation and Validation

- Action: Assess the model's robustness and predictive performance.

- Visual Predictive Check (VPC): Simulate multiple trials using the final model and compare the simulation intervals with the observed data [4]. Advanced methods like V2ACHER-transformed VPC (V3PC) can improve interpretability for models with multiple covariates [4].

- Bootstrap: Re-estimate model parameters on multiple resampled datasets to evaluate parameter precision.

- Goodness-of-Fit Plots: Examine observed vs. population-predicted and individual-predicted values, and conditional weighted residuals.

Step 7: Clinical Trial Simulation and Decision Making

- Action: Use the qualified PopPK/PD model to simulate virtual clinical trials.

- Process: Simulate drug exposure and response for thousands of virtual subjects under various dosing regimens and patient population scenarios.

- Application: Compare the probability of achieving a target efficacy/safety metric across different doses to support dose justification and label recommendations.

Advanced Integration: Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) in Anti-Infectives

For more complex questions, such as predicting the emergence of resistance, a QSP approach is warranted. The following diagram outlines the structure of a simplified QSP model for an antiviral drug.

QSP Protocol Outline:

- Model Scope Definition: Define the key biological system components (e.g., host immune cells, different viral subpopulations, intracellular drug kinetics).

- System Assembly: Construct a network of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) based on known pathophysiology and drug mechanisms.

- Parameterization: Gather system parameters from literature and pre-clinical data. Use optimization techniques to estimate unknown parameters.

- Validation: Challenge the model by comparing its simulations to clinical trial outcomes not used for model building.

- Scenario Exploration: Use the validated model to simulate the long-term outcomes of various combination therapies and dosing strategies on resistance suppression.

Pharmacometrics provides the formal, quantitative framework essential for integrating PK, PD, and disease biology into a cohesive model-informed drug development strategy. The application notes and protocols detailed herein offer a practical roadmap for implementing these powerful methodologies in anti-infective research. By adopting these approaches—from foundational PopPK/PD to advanced QSP modeling—researchers can significantly de-risk development, optimize therapy for individual patients, and combat the ever-present threat of antimicrobial resistance more effectively. The ongoing integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning promises to further refine these models, enhancing their predictive power and solidifying their role as a cornerstone of modern therapeutics development [2] [5].

Application Note: Pharmacometric Modeling in Anti-Infective Development

Background and Rationale

The global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis represents one of the most significant public health threats of the 21st century, projected to cause 10 million deaths annually by 2050 if unmitigated [6]. The development of anti-infective therapies faces unique challenges, including the rapid evolution of resistant pathogens and economic disincentives for traditional antibiotic development [7]. Quantitative approaches, particularly pharmacometric modeling and simulation (M&S), have emerged as indispensable tools to optimize anti-infective drug development and combat AMR through data-driven decision support [8].

Pharmacometrics integrates mathematical models based on biology, pharmacology, physiology, and disease to quantify drug-patient interactions [8]. This application note outlines how pharmacometric approaches address key challenges in anti-infective development, including optimizing dosage regimens, predicting resistance development, and supporting regulatory decisions across the drug development continuum [8].

Quantitative Framework Implementation

The pharmacometric workflow integrates data from multiple sources to characterize pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) relationships and predict clinical outcomes. Table 1 summarizes the primary quantitative modeling approaches employed in anti-infective development.

Table 1: Pharmacometric Modeling Approaches in Anti-Infective Development

| Model Type | Primary Application | Key Outputs | Software Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population PK (popPK) | Characterize drug exposure variability in patient populations | Parameter variability estimates, Covariate effects | NONMEM, Monolix, Phoenix WinNonlin |

| PK/PD Modeling | Establish exposure-response relationships for efficacy and safety | Target attainment analysis, Dose optimization | NONMEM, R, Phoenix WinNonlin |

| Mechanistic Systems Models | Predict resistance development and population dynamics | Resistance probability, Optimal combination therapies | MATLAB, R, Custom implementations |

| Transational PK/PD | Bridge preclinical findings to human predictions | First-in-human dosing, Therapeutic window estimation | Simulx, PK-Sim, GastroPlus |

Key Quantitative Parameters and Targets

Table 2 outlines critical PK/PD indices and their target values for major anti-infective classes, derived from pharmacometric analyses [8].

Table 2: Key PK/PD Targets for Anti-Infective Agents

| Anti-Infective Class | Primary PK/PD Index | Target Value | Pathogen Example | Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoroquinolones | fAUC/MIC | 100-250 | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Community-acquired pneumonia |

| β-Lactams | fT>MIC | 30-70% (varies by agent) | Staphylococcus aureus | Nosocomial infections |

| Glycopeptides | AUC/MIC | ≥400 | Staphylococcus aureus | Gram-positive infections |

| Aminoglycosides | Cmax/MIC | 8-12 | Gram-negative bacilli | Serious infections |

| Oxazolidinones | fAUC/MIC | 80-120 | MRSA | Skin and soft tissue infections |

Protocol: Development and Validation of Pharmacometric Models for Anti-Infectives

Protocol: Population PK Model Development

Objective

To develop a population pharmacokinetic (popPK) model that characterizes drug disposition and identifies sources of variability in target patient populations.

Materials and Equipment

- Pharmacokinetic concentration-time data

- Patient demographic data (age, weight, renal/hepatic function)

- Concomitant medication records

- NONMEM, Monolix, or equivalent modeling software

- R or Python for data preparation and diagnostics

Experimental Procedure

- Data Assembly: Compile PK samples with accurate recording of sampling times, doses, and administration routes. Include relevant patient covariates.

- Structural Model Development:

- Plot concentration-time data and evaluate appropriate structural models (1-, 2-, 3-compartment)

- Test absorption models (zero/first-order, transit compartments)

- Estimate parameters (clearance, volume, absorption rate)

- Statistical Model Development:

- Characterize between-subject variability using exponential error models

- Model residual variability using proportional, additive, or combined error structures

- Covariate Model Development:

- Evaluate relationships between parameters and physiologic covariates

- Use stepwise forward inclusion (p<0.05) and backward elimination (p<0.01)

- Validate final model using visual predictive checks and bootstrap analysis

Data Analysis

- Generate parameter estimates with precision (relative standard error)

- Calculate shrinkage for empirical Bayesian estimates

- Perform model qualification using diagnostic plots and simulation-based evaluations

Protocol: PK/PD Target Attainment Analysis

Objective

To determine the probability of achieving predefined PK/PD targets across a population using Monte Carlo simulations.

Materials and Equipment

- Final popPK model with parameter distributions

- Pathogen MIC distributions from surveillance data

- Preclinical PK/PD targets (e.g., fT>MIC, fAUC/MIC)

- R, SAS, or other simulation software

Experimental Procedure

- Define PK/PD Target: Identify relevant index and target value based on preclinical infection models (refer to Table 2).

- Set Up Simulation:

- Simulate concentration-time profiles for 10,000 subjects using final popPK model

- Incorporate parameter uncertainty and covariate distributions

- Calculate PK/PD Index:

- For each simulated subject, compute the relevant PK/PD index

- Compare to preclinical target value

- Determine Probability of Target Attainment (PTA):

- Calculate percentage of subjects achieving target at each MIC

- Plot PTA versus MIC to determine susceptibility breakpoints

Data Analysis

- Identify MIC where PTA falls below 90% (susceptibility breakpoint)

- Generate PTA curves for multiple dosing regimens to support dose selection

- Integrate epidemiologic MIC data to estimate cumulative fraction of response

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Pharmacometric Modeling Workflow

Anti-Infective PK/PD Relationship Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Anti-Infective Pharmacometrics

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modeling Software | NONMEM | Nonlinear mixed-effects modeling | Population PK/PD model development |

| Modeling Software | Monolix | Parameter estimation using SAEM algorithm | PK/PD model development and diagnostics |

| Modeling Software | R with packages (nlme, ggplot2) | Data visualization and statistical analysis | Exploratory data analysis and plotting |

| Simulation Tools | Simulx | Clinical trial simulation | Study design optimization |

| Simulation Tools | Phoenix WinNonlin | Non-compartmental analysis | Initial PK parameter estimation |

| Data Standards | CDISC SEND | Nonclinical data standardization | Regulatory submission preparation |

| Data Standards | CDISC SDTM/ADaM | Clinical data standardization | Regulatory submission preparation |

| Bioanalytical | LC-MS/MS systems | Drug concentration quantification | PK sample analysis |

| Microbiological | Broth microdilution | MIC determination | PD input parameter generation |

| Clinical Data | Electronic Data Capture (EDC) | Clinical trial data management | Efficient data collection and cleaning |

Advanced Applications: Integrating AI and Machine Learning

Recent advances have integrated artificial intelligence with traditional pharmacometric approaches to address AMR [9]. The novel BARDI framework (Brokered data-sharing, AI-driven Modelling, Rapid diagnostics, Drug discovery, and Integrated economic prevention) exemplifies this integration, using machine learning to enhance predictive modeling of resistance development and optimize combination therapies [9].

Quantitative modeling of population dynamics using both mechanistic models and machine learning approaches shows particular promise for predicting AMR emergence and spread [10]. These integrated models can account for non-genetic heterogeneity in microbial populations, which contributes to the development of resistance through fluctuations in gene expression even in clonal populations [11].

The application of these quantitative tools represents a paradigm shift in anti-infective development, enabling more efficient dose selection, optimized clinical trial designs, and ultimately, more effective strategies for combating antimicrobial resistance through data-driven approaches.

In the face of increasing antimicrobial resistance, the optimization of anti-infective therapy through Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) principles has become paramount. PK/PD integration comprehensively analyzes the relationships between drug exposure, microbial response, and clinical outcome, providing a scientifically robust framework for rational dosage regimen design and treatment optimization [12] [13]. These models are indispensable tools in pharmaceutical development, academia, and regulatory agencies for bridging preclinical findings and clinical application [13]. The core indices that predict antibiotic efficacy—fAUC/MIC, T>MIC, and fCmax/MIC—serve as critical guides for maximizing bacterial kill and suppressing resistance emergence. This article details these fundamental PK/PD indices within the context of pharmacometric modeling and simulation, providing structured data and experimental protocols for their application in anti-infective development.

Core PK/PD Indices: Definitions and Target Values

Antibiotics are traditionally categorized based on their pattern of bacterial killing and the PK/PD index most predictive of their efficacy. The "f" prefix denotes the unbound, pharmacologically active fraction of the drug [12].

Table 1: Core PK/PD Indices and Their Characteristics

| PK/PD Index | Definition | Antibiotic Classes | Primary Goal of Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

fAUC/MIC |

Ratio of the area under the unbound drug concentration-time curve to the MIC [12]. | Fluoroquinolones, Vancomycin, Tetracyclines, Azithromycin, Tigecycline, Daptomycin, Colistin [14] [15] [16] | Maximize the overall drug exposure over time. |

%T > MIC |

Percentage of the dosing interval that the unbound drug concentration exceeds the MIC [12]. | β-lactams (Penicillins, Cephalosporins, Carbapenems), Erythromycin, Linezolid [14] [15] | Maximize the duration of contact between the drug and the bacterium. |

fCmax/MIC |

Ratio of the maximum unbound drug concentration to the MIC [12]. | Aminoglycosides, Metronidazole, likely Rifampin [15] | Maximize the peak drug concentration. |

Table 2: Representative PK/PD Target Values for Efficacy

| Antibiotic / Class | PK/PD Index | Target for Efficacy | Notes / Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides | Cmax/MIC |

8-10 [14] | Target associated with preventing resistance. |

| Vancomycin | AUC/MIC |

≥400 [14] | Target for MRSA; associated with reduced mortality and treatment failure [14]. |

| Fluoroquinolones (vs S. pneumoniae) | AUC/MIC |

>33.7 [14] | Linked to 100% microbiological response [14]. |

| β-Lactams | %T > MIC |

60-70% of dosing interval [14] | For maximum killing; newer evidence suggests benefit of 100% coverage [15]. |

| Colistin (vs A. baumannii) | fAUC/MIC |

Stasis: 1.57-7.41; 1-log kill: 6.98-42.1 [17] [16] | Target varies by strain and infection site (thigh vs. lung) [17]. |

| Daptomycin | AUC/MIC |

>600 [15] | Requires doses of 6-12 mg/kg/day depending on MIC [15]. |

| Linezolid | AUC/MIC |

100 [15] | May require increased dosing frequency for strains with MICs at the breakpoint [15]. |

Diagram 1: A workflow for selecting the primary PK/PD index and corresponding dosing strategy based on antibiotic classification. (PAE: Post-Antibiotic Effect).

Experimental Protocols for PK/PD Index Determination

Determining which PK/PD index best predicts an antibiotic's efficacy requires well-designed experiments. The following protocols outline the key methodologies.

In Vitro PK/PD Model (Hollow Fiber/Peristaltic Pump System)

This system simulates human PK in a controlled environment to characterize the exposure-response relationship without host immune interference [12].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Hollow Fiber Bioreactor: A cartridge with semi-permeable membranes simulating a central compartment; allows for dynamic drug concentration changes and bacterial sampling without dilution [12].

- Cation-Adjusted Mueller Hinton Broth (CAMHB): Standardized growth medium ensuring robust and reproducible bacterial growth [17].

- Test Organism: Prepared early logarithmic-phase bacterial suspension (e.g., ~10⁷ CFU/mL) to simulate active infection [17].

Procedure:

- Inoculation: Inject the bacterial suspension into the central compartment of the hollow fiber system.

- Drug Administration: Simulate human PK profiles by administering antibiotic regimens into the system's central compartment. For dose-fractionation studies, administer the same total daily dose using different dosing intervals (e.g., Q24h, Q12h, Q8h) [17].

- Sampling: Collect samples from the central compartment at predetermined time points over 24-48 hours for both:

- Data Analysis: Plot time-kill curves. Use non-linear regression analysis to correlate the observed antibacterial effect (e.g., change in log₁₀ CFU at 24h) with the three PK/PD indices (

fAUC/MIC,%fT>MIC,fCmax/MIC). The index with the highest coefficient of determination (R²) is the most predictive [17].

In Vivo PK/PD Model (Murine Thigh/Lung Infection)

This model studies the complex interplay between host, pathogen, and drug, providing critical data for translating in vitro findings to a living system [17] [12].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Immunocompromised Host: Female Swiss albino mice rendered neutropenic via intraperitoneal cyclophosphamide (150 mg/kg 4 days prior, 100 mg/kg 1 day prior) to blunt innate immune response [17].

- Infection Inoculum: Prepare early logarithmic-phase bacterial suspension in sterile saline (~10⁷ CFU/mL for thigh; ~10⁸ CFU/mL for lung infection) [17].

- Test Article: Colistin sulphate solution, freshly prepared in water and filter-sterilized (0.2 µm) before each experiment [17].

Procedure:

- Infection Establishment:

- Treatment Initiation: Commence therapy (e.g., subcutaneous injections) 2 hours post-inoculation [17].

- Dose Fractionation Design: Administer a range of total daily doses (e.g., 1-160 mg/kg/day for colistin) fractionated into different intervals (e.g., every 6, 8, 12, or 24 hours) [17].

- Endpoint Analysis: Humanely euthanize mice 24 hours after treatment initiation. Aseptically remove and homogenize target organs (thighs/lungs). Perform quantitative cultures on homogenates to determine the bacterial burden [17].

- PK/PD Integration & Population Analysis:

- Integration: Use previously established plasma PK profiles to calculate the

fAUC/MIC,%fT>MIC, andfCmax/MICfor each regimen. Correlate these values with the measured bacterial burden to identify the predictive index [17]. - Resistance Monitoring: Spiral plate tissue homogenates onto agar plates containing increasing concentrations of colistin (e.g., 0.5 to 10 mg/L) to generate Population Analysis Profiles (PAPs) and monitor the amplification of resistant subpopulations [17].

- Integration: Use previously established plasma PK profiles to calculate the

Diagram 2: A side-by-side comparison of the experimental workflows for determining the predictive PK/PD index using in vitro and in vivo models. (PAPs: Population Analysis Profiles).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Instruments for PK/PD Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller Hinton Broth (CAMHB) | Standardized medium for broth microdilution MIC determination and in vitro PK/PD model inoculum preparation [17]. | Ensuring reproducible bacterial growth and reliable MIC results [17]. |

| Hollow Fiber Infection Model (HFIM) | In vitro system that simulates human PK profiles for antibiotics against bacteria in a dynamic, closed system [12]. | Performing robust dose-fractionation studies to identify the PK/PD driver without animal use [12]. |

| Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Highly sensitive and specific analytical technique for quantifying drug concentrations in complex biological matrices [18]. | Measuring antibiotic concentrations in plasma, tissue homogenates, and in vitro samples for PK analysis [18]. |

| Confocal Raman Spectroscopy | Label-free, non-destructive technique for measuring local drug concentration distributions in tissues and gels [18]. | Mapping drug penetration and gradients in tissue specimens, complementing LC-MS/MS data [18]. |

| Tissue Homogenizer (e.g., Polytron) | Instrument for homogenizing solid tissues into a uniform suspension for subsequent analysis. | Preparing homogeneous samples from infected murine thighs or lungs for CFU counting and drug assay [17]. |

| Spiral Plater (e.g., WASP2) | Automated instrument for depositing liquid samples in an Archimedean spiral on agar plates for bacterial counting. | Performing rapid and accurate quantitative cultures on serial dilutions of tissue homogenates or in vitro samples [17]. |

The strategic application of PK/PD principles is fundamental to modern anti-infective development and therapy. A deep understanding of the core indices—fAUC/MIC, %T>MIC, and fCmax/MIC—enables researchers and clinicians to design dosing regimens that maximize efficacy and minimize the potential for resistance. As the field evolves, integrating these principles with advanced pharmacometric modeling and novel experimental approaches, such as physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models and enhanced in vitro systems, will be crucial for optimizing the use of existing antibiotics and guiding the development of new agents against multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) is defined as the strategic use of computational modeling and simulation (M&S) methods that integrate nonclinical and clinical data, prior information, and knowledge to generate evidence [1]. In the critical field of anti-infective research, pharmacometric modeling and simulation has emerged as an indispensable tool for addressing the global challenge of antimicrobial resistance and optimizing treatment regimens for established antimicrobials [8] [19]. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) M15 guidelines, released for public consultation in November 2024, establish a harmonized framework for MIDD applications, aiming to align expectations between regulators and sponsors while supporting consistent regulatory decisions [1].

The model-based continuum spans from early preclinical discovery through clinical development and into lifecycle management, with pharmacometrics serving as the backbone that connects knowledge across stages. This approach is particularly valuable for anti-infective development, where it facilitates the integration of preclinical and clinical data to provide a scientifically rigorous framework for rational dosage regimen design and treatment optimization [8]. By leveraging quantitative approaches such as population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PopPK-PD) modeling and quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP), researchers can characterize the complex relationships between drug exposure, microbial killing, and resistance emergence, ultimately accelerating the delivery of novel anti-infective therapies to patients [8] [20].

Theoretical Framework and Key Methodologies

The Pharmacometric Modeling Spectrum

The MIDD framework encompasses a diverse spectrum of modeling approaches, each with distinct applications across the drug development continuum. Population PK-PD (PopPK-PD) modeling, typically leveraging nonlinear mixed-effects modeling of compartmental PK and PD models, has emerged as a preeminent methodology for dose-exposure-response (E-R) predictions in MIDD [1]. These models are particularly effective for characterizing variability in drug concentrations and effects between subjects, as well as for performing clinical trial simulations [1].

Physiologically based PK (PBPK) modeling represents another crucial methodology, with approximately 70% of its applications in drug development and regulatory settings focused on predicting drug-drug interactions with enzymes and transporters [1]. For anti-infectives, this is particularly relevant for complex combination therapies used for drug-resistant infections. More recently, Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) has gained prominence as a mechanistic modeling approach that incorporates the (patho)physiology of interest, mechanistic links between target modulation and key endpoints, overall system dynamics, population variability, and pharmacological interventions [20].

The International Society of Pharmacometrics (ISoP) special interest groups (SIGs) have articulated how these diverse modeling approaches integrate into MIDD decision-making [20]. The selection of the appropriate model class begins with understanding the specific research question and available data, ranging from simple statistical models to complex mechanistic models depending on the development stage and decision context [20].

Key Pharmacodynamic Parameters for Anti-Infectives

For anti-infective drugs, specific pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) indices have been established as critical predictors of efficacy. These parameters form the foundation of exposure-response modeling in antimicrobial development and are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key PK-PD Parameters for Anti-Infective Efficacy

| PK-PD Index | Drug Class | Target Value | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| fAUC/MIC | Fluoroquinolones | 30-100 | Predicts concentration-dependent killing |

| %T>MIC | β-Lactams | 30-70% | Time-dependent bacterial killing |

| fCmax/MIC | Aminoglycosides | 8-10 | Concentration-dependent killing and post-antibiotic effect |

The application of these PK-PD targets is well illustrated by garenoxacin, where a pharmacometric analysis determined that a fAUC₀⁻²⁴/MIC₉₀ ratio >200 supported a 400 mg QD oral dosing regimen as safe and effective for community-acquired pneumonia [8]. Similarly, moxifloxacin demonstrated target attainment rates exceeding 95% for respiratory tract infections when the fAUC₀⁻²⁴/MIC₉₀ ratio reached 120 in epithelial lining fluid [8].

Application Notes: Implementing MIDD Across the Development Continuum

Preclinical to Clinical Translation

The transition from preclinical models to first-in-human studies represents a critical juncture in anti-infective development. Model-based approaches significantly enhance this translation by integrating in vitro and animal model data to inform human dosing predictions. For instance, PK-PD models that incorporate data from murine thigh and lung infection models can establish exposure targets for human efficacy, effectively bridging the gap between preclinical results and clinical trial design [8].

The integration of QSP and clinical pharmacometrics occurs through three primary paradigms: (1) parallel synchronization, where independent efforts serve as cross-validation; (2) cross-informative use, where one approach informs the other; and (3) sequential integration, where one approach precedes the other, creating a framework that can inform decisions along the entire research and development continuum [20]. This integration is particularly valuable for novel therapies with limited clinical data, such as those targeting multidrug-resistant pathogens.

A notable example of successful translation involves the dose selection of pembrolizumab, where cross-validation efforts between modeling approaches strengthened confidence in the recommended dosing strategy [20]. Similarly, a large QSP model of the cardio-renal system helped explain the unexpected cardioprotective effect of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure, demonstrating how mechanistic modeling can provide insights into drug effects beyond the primary indication [20].

Clinical Development Optimization

During clinical development, PopPK-PD modeling becomes indispensable for characterizing variability in drug exposure and response across diverse patient populations. These analyses are particularly important for anti-infectives, which are often used in patients with organ dysfunction, critical illness, or other comorbidities that alter drug pharmacokinetics. For example, population PK analyses of norvancomycin identified that clearance was correlated with creatinine clearance (CL=2.54(CLCr/50)) in patients with renal dysfunction, enabling optimized dosing in this special population [8].

The use of modeling and simulation in clinical development enables the quantitative integration of knowledge across the development program and compounds, addressing a broader range of dose-exposure responses, product design, special populations, and disease-related questions than traditional statistical approaches alone [1]. This approach has proven particularly valuable in special populations such as pediatric patients, where MIDD has enabled accelerated approvals of drugs for pediatric conditions and rare diseases where recruiting sufficient patients for efficacy studies is challenging [1].

Table 2: Clinical Pharmacometrics Case Studies in Anti-Infective Development

| Drug | Population | Key Analysis | Outcome/Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cefditoren | Lower respiratory tract infections | PD profiling & probability of target attainment (PTA) | PTA <80% at T>MIC of 33% (MIC=0.06mg/L) with 400 mg QD [8] |

| Ceftobiprole | Nosocomial pneumonia | PD profiling & renal dose adjustments | 500 mg BID optimal for CrCl ≤50 mL/min [8] |

| Oseltamivir | Neonates and infants | Population PK modeling | 3 mg/kg BID in infants; 1.7 mg/kg BID in neonates [8] |

| Piperacillin/Tazobactam | Gram-negative infections | PK/PD parameters & in vivo effectiveness | Doses of 3.375g Q4h-Q6h and 4.5g Q6h-Q8h provided adequate target attainment [8] |

The ICH M15 guidelines formalize the MIDD process through defined stages: Planning and Regulatory Interaction, Implementation, Evaluation, and Submission [1]. This structured approach begins with planning that defines the Question of Interest (QOI), Context of Use (COU), Model Influence, Decision Consequences, Model Risk, Model Impact, Appropriateness, and Technical Criteria – all documented in a Model Analysis Plan (MAP) [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Integrated PopPK-PD Model Development for Anti-Infectives

Objective: To develop a population PK-PD model that characterizes the relationship between drug exposure, microbial killing, and resistance emergence for a novel anti-infective compound.

Materials and Reagents:

- Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Modeling Software: NONMEM, Monolix, or equivalent for parameter estimation [1]

- Data Assembly Tools: R, Python, or SAS for dataset creation and exploratory analysis [8]

- Pharmacometric Dataset: Including drug concentrations, pathogen MIC values, patient demographics, and clinical outcomes [8]

- Model Diagnostic Tools: Visual predictive checks, goodness-of-fit plots, bootstrap analyses [1]

Methodology:

- Data Compilation: Assemble rich or sparse PK sampling data from phase 1 and phase 2 trials, including patient covariates (weight, renal/hepatic function, age) and pathogen-specific MIC values [8].

- Structural Model Development:

- Test compartmental PK models (1-, 2-, 3-compartment) with first-order or Michaelis-Menten elimination

- Develop PD model linking plasma concentrations to microbial killing using Emax models or similar functions

- Incorporate natural disease progression and placebo effects where applicable

- Stochastic Model Building:

- Characterize between-subject variability on key parameters using exponential error models

- Define residual error models (additive, proportional, or combined)

- Implement correlation between random effects if supported by data

- Covariate Model Development:

- Evaluate relationship between patient factors (e.g., renal function) and PK parameters using stepwise covariate modeling

- Validate final covariate relationships using visual predictive checks and bootstrap procedures

- Model Validation:

- Conduct internal validation through data splitting, bootstrap, or cross-validation techniques

- Perform external validation with independent datasets when available

- Evaluate predictive performance through visual predictive checks and numerical predictive checks

Output Applications:

- Simulation of various dosing regimens to determine probability of target attainment

- Identification of patient subgroups requiring dose adjustments

- Optimization of sampling schedules for future trials

Protocol: QSP Model for Resistance Development in Antibacterial Drugs

Objective: To develop a mechanistic QSP model that predicts the emergence of bacterial resistance under different drug exposure scenarios.

Materials and Reagents:

- Systems Modeling Software: MATLAB/Simulink, Julia, or specialized QSP platforms [20]

- Biological Data: In vitro time-kill curves, resistance frequency measurements, genomic data on resistance mechanisms

- Physiological Parameters: Bacterial growth rates, mutation rates, fitness costs of resistance

Methodology:

- Model Scope Definition:

- Define the biological system: bacterial population dynamics, drug-target interactions, resistance mechanisms

- Establish model boundaries and level of mechanistic detail based on the QOI

- Virtual Patient Population:

- Create virtual patients (VPs) representing credible observations in the parameter space

- Ensure VPs are consistent with observed pathophysiology and response to therapies [20]

- Mathematical Model Implementation:

- Implement bacterial subpopulations (susceptible, resistant) with different growth and killing rates

- Incorporate drug pharmacokinetics and PD effects on bacterial killing

- Include mutation rates between subpopulations and fitness costs of resistance

- Model Calibration and Validation:

- Calibrate model parameters against in vitro time-kill data and resistance emergence studies

- Validate model predictions using in vivo data from preclinical infection models

- Conduct sensitivity analyses to identify key parameters driving resistance emergence

- Simulation and Scenario Testing:

- Simulate various dosing regimens and their impact on resistance development

- Identify exposure thresholds associated with rapid resistance emergence

- Optimize dosing strategies to suppress resistance while maintaining efficacy

Output Applications:

- Guidance on optimal dosing strategies to minimize resistance emergence

- Identification of pharmacological properties desirable for resistance suppression

- Support for regulatory submissions regarding resistance risk management

Visualization of Workflows and Signaling Pathways

MIDD Workflow in Anti-Infective Development

MIDD Development Cycle

This diagram illustrates the iterative knowledge integration throughout the model-based drug development continuum, from preclinical data generation through regulatory submission.

Anti-Infective PK-PD Modeling Framework

PK-PD Modeling Framework

This workflow depicts the fundamental relationships in anti-infective pharmacometrics, connecting drug administration to pharmacological effects through measurable exposure parameters and their resulting biological responses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of model-based approaches in anti-infective development requires specialized tools and methodologies. The following table summarizes key resources essential for pharmacometric analyses in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Anti-Infective Pharmacometrics

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modeling & Simulation Software | NONMEM, Monolix, Phoenix NLME | Population PK-PD model development and parameter estimation | Nonlinear mixed-effects modeling, covariate analysis, simulation capabilities [1] |

| Systems Modeling Platforms | MATLAB/Simulink, Julia, R | QSP model implementation and simulation | Differential equation solving, parameter estimation, model calibration [20] |

| Data Management & Analysis | R, Python, SAS | Dataset creation, exploratory analysis, model diagnostics | Data visualization, statistical analysis, automated reporting [8] |

| PBPK Modeling Platforms | GastroPlus, Simcyp, PK-Sim | Prediction of drug absorption, distribution, and drug-drug interactions | Physiology-based parameters, special population modules [1] |

| Clinical Trial Simulation | Trial Simulator, East | Design and simulation of clinical trials | Power analysis, sample size estimation, adaptive design evaluation |

The integration of these tools creates a comprehensive ecosystem for model-based anti-infective development. As noted in the ICH M15 guidelines, the MIDD framework encompasses a broad range of quantitative methods, including PopPK, PBPK, dose-exposure-response analysis, model-based meta-analysis, QSP, and increasingly, AI/ML methods [1]. The selection of specific tools should be guided by the Question of Interest (QOI) and Context of Use (COU) defined in the Model Analysis Plan (MAP) as recommended by the ICH M15 guidelines [1].

The model-based drug development continuum represents a transformative approach to anti-infective research, integrating knowledge from preclinical discoveries through clinical applications. By implementing pharmacometric modeling and simulation strategies, researchers can optimize dosage selection, identify patient factors influencing drug exposure and response, and develop strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance. The standardized methodologies and protocols outlined in these application notes provide a framework for implementing MIDD in anti-infective development programs, with the potential to accelerate the delivery of novel therapies to patients facing resistant infections.

The adoption of model-based approaches continues to gain regulatory endorsement, as evidenced by the ICH M15 guidelines and the successful case studies across various therapeutic areas [1]. As the field advances, the integration of emerging technologies such as AI/ML with traditional pharmacometric methods promises to further enhance the efficiency and predictive performance of model-based strategies in anti-infective drug development [1] [20].

From Model to Medicine: Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Anti-Infectives

Model-informed drug development (MIDD) has a long and rich history in infectious diseases, playing a pivotal role in the development of anti-infective therapies by quantitatively integrating pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) data. Pharmacometric modeling transforms complex biological systems into mathematical frameworks that describe the complete time course of the dose-response relationship, enabling more efficient drug development and optimized dosing regimens for clinical practice [21] [22]. In anti-infective research, these models are particularly valuable as they allow researchers to characterize and translate antibiotic effects, ultimately supporting the development of new therapeutic agents and treatment strategies against resistant pathogens [23].

The foundational principle of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling lies in establishing mathematical relationships between administered doses, resulting drug concentrations in the body (pharmacokinetics), and the subsequent pharmacological effects (pharmacodynamics). This integrated approach provides a quantitative framework for predicting drug behavior and effects across different patient populations and dosing scenarios, making it an indispensable tool in the clinical pharmacologist's arsenal [21] [24]. For anti-infective agents, PK/PD modeling has become particularly crucial for designing effective dosing strategies that maximize efficacy while minimizing the development of antimicrobial resistance [25].

Compartmental Pharmacokinetic (PK) Modeling

Fundamental Principles and Model Types

Compartmental pharmacokinetic modeling is a mathematical approach that describes the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of drugs within the body by grouping tissues and fluids with similar pharmacokinetic properties into hypothetical compartments [26] [27]. These compartments do not necessarily represent specific anatomical tissues but rather functional spaces with distinct kinetic characteristics. The primary objective of compartmental modeling is to simplify the body's complexity into manageable, quantifiable systems that can predict drug behavior based on various structural configurations [27].

Table 1: Types of Compartmental Pharmacokinetic Models

| Model Type | Structural Components | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-Compartment | Single central compartment | Assumes instantaneous, uniform drug distribution; first-order elimination | Preliminary PK analysis; drugs with rapid distribution [26] [27] |

| Two-Compartment | Central + Peripheral compartments | Accounts for distribution phase; more accurately reflects tissue distribution | Drugs showing biphasic elimination; many antibiotics and antivirals [26] [27] |

| Three-Compartment | Central + Two Peripheral compartments | Further subdivision of distribution phases; complex kinetics | Drugs with deep tissue distribution; specialized anti-infectives [26] [27] |

| Physiologically-Based PK (PBPK) | Multiple organ- and tissue-specific compartments | Grounded in biological and physiological data; highly mechanistic | First-in-human dose prediction; drug-drug interaction studies [26] [25] |

Mathematical Foundation

The one-compartment model with intravenous administration represents the simplest form, where the entire body is treated as a single homogeneous unit. The differential equation describing this model is:

dA/dt = -k × A

where A is the amount of drug in the body, and k is the first-order elimination rate constant. The integrated form yields:

C = (Dose/V) × e^(-k×t)

where C is the drug concentration at time t, and V is the apparent volume of distribution [26].

For a two-compartment model with intravenous administration, the system is described by two differential equations:

dA₁/dt = k₂₁ × A₂ - k₁₂ × A₁ - k₁₀ × A₁ dA₂/dt = k₁₂ × A₁ - k₂₁ × A₂

where A₁ and A₂ represent the amount of drug in the central and peripheral compartments, respectively; k₁₂ and k₂₁ are distribution rate constants between compartments; and k₁₀ is the elimination rate constant from the central compartment [26].

Application Protocol: Establishing a Compartmental PK Model

Objective: To develop and validate a compartmental PK model for a novel anti-infective compound.

Materials and Reagents:

- Test compound (API)

- Animal model (e.g., mice, rats) or human subjects

- Appropriate formulation vehicles

- Blood collection tubes (containing anticoagulant)

- Analytical standards for calibration

- LC-MS/MS system for bioanalysis

- PK modeling software (e.g., NONMEM, Monolix, Phoenix WinNonlin)

Procedure:

- Study Design: Administer the test compound via relevant route (IV for complete bioavailability assessment, plus other intended routes). Implement dense sampling strategy (10-15 timepoints) during the elimination phase to characterize distribution and elimination.

- Bioanalytical Method: Validate a sensitive and specific analytical method (typically LC-MS/MS) for quantifying compound concentrations in plasma. Ensure the calibration curve covers the expected concentration range with acceptable accuracy and precision.

- Sample Collection and Analysis: Collect blood samples at predetermined timepoints, process to plasma, and analyze using the validated method.

- Data Preparation: Prepare dataset containing compound concentrations, sampling times, dose information, and relevant subject covariates.

- Model Development:

- Begin with structural model identification using one-, two-, or three-compartment models.

- Incorporate appropriate absorption models for extravascular administration (e.g., first-order, zero-order, or more complex absorption models).

- Implement statistical model to account for interindividual variability and residual error.

- Model Evaluation: Assess model performance using diagnostic plots, visual predictive checks, and precision of parameter estimates.

- Model Application: Utilize the final model for simulations to predict exposure under different dosing regimens and in specific populations.

Diagram 1: Structure of a Two-Compartment Pharmacokinetic Model

Pharmacodynamic (PD) Modeling: Emax and Sigmoid Emax Models

Theoretical Basis and Mathematical Formulation

Pharmacodynamic modeling quantitatively describes the relationship between drug concentration at the effect site and the pharmacological response. For anti-infective drugs, this typically represents the relationship between antimicrobial concentrations and the reduction in bacterial populations [22]. The most fundamental PD models include the fixed-effect, linear, log-linear, maximum effect (Emax), and sigmoid Emax models, with the latter two being most prevalent in anti-infective PK/PD modeling [22].

The sigmoid Emax model is particularly valuable as it can describe a wide range of concentration-effect relationships, from shallow to steep curves, making it applicable to various anti-infective mechanisms. The mathematical equation for the sigmoid Emax model is:

E = E₀ + (Emax × Cⁿ) / (EC₅₀ⁿ + Cⁿ)

where E is the measured effect, E₀ is the baseline effect in the absence of drug, Emax is the maximum possible effect, C is the drug concentration at the effect site, EC₅₀ is the drug concentration that produces 50% of the maximum effect, and n is the Hill coefficient that determines the steepness of the concentration-effect curve [22].

Table 2: Parameters of the Sigmoid Emax Model

| Parameter | Definition | Biological Interpretation | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| E₀ | Baseline effect | Effect in absence of drug | Variable (e.g., CFU/mL) |

| Emax | Maximum effect | Maximum achievable drug effect | Same as E₀ |

| EC₅₀ | Half-maximal effective concentration | Drug potency; lower value indicates higher potency | Concentration (e.g., mg/L) |

| n | Hill coefficient | Steepness of concentration-effect relationship; reflects cooperative binding | Unitless |

Application Protocol: Implementing PD Models for Anti-Infective Agents

Objective: To characterize the concentration-effect relationship of an antimicrobial agent using the sigmoid Emax model.

Materials and Reagents:

- Test antimicrobial agent

- Reference bacterial strains with known MIC values

- Mueller-Hinton broth or other appropriate culture media

- Sterile 96-well plates or test tubes

- Incubator

- Spectrophotometer for turbidity measurements

- Colony counting equipment (agar plates, colony counter)

Procedure:

- Preparation of Drug Dilutions: Prepare a range of drug concentrations (typically 0.25× to 64× MIC) using serial dilution methods in appropriate culture media.

- Inoculum Preparation: Adjust bacterial suspensions to approximately 10⁵-10⁶ CFU/mL in fresh culture media.

- Exposure and Incubation: Combine equal volumes of drug dilutions and bacterial suspensions in sterile plates or tubes. Include growth controls (no drug) and sterility controls (no bacteria).

- Effect Measurement: Incubate under appropriate conditions for a predetermined time (typically 18-24 hours for bacteria). Measure the antibacterial effect using viable count methods (determining CFU/mL) or optical density for growth inhibition.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage of growth inhibition or log reduction in CFU/mL compared to growth controls.

- Plot effect measures against drug concentrations.

- Fit the sigmoid Emax model to the data using nonlinear regression.

- Estimate model parameters (E₀, Emax, EC₅₀, n) with associated measures of precision.

- Model Validation: Assess model goodness-of-fit through residual analysis, visual inspection, and comparison with simpler models (e.g., linear, Emax without sigmoidicity).

Diagram 2: Pharmacodynamic Modeling Approaches

Time-Kill Curve Modeling

Conceptual Framework and Advantages

Time-kill curve analysis represents a dynamic approach to characterizing antimicrobial effects by measuring changes in bacterial density over time when exposed to varying antibiotic concentrations [28]. Unlike static MIC-based approaches, time-kill curves capture the kinetics of microbial killing and growth as a function of both time and antibiotic concentration, providing a more comprehensive assessment of the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationship [28] [29].

The primary advantage of time-kill curve approaches lies in their ability to characterize the rate and extent of bactericidal activity, detect regrowth due to resistance emergence, and identify concentration-dependent versus time-dependent killing patterns [28]. This method allows researchers to directly compare the effects of various concentration profiles and provides a more detailed assessment of the PK/PD relationship than simple MIC-based determinations [28].

Mathematical Implementation

Mechanism-based PK/PD models for antimicrobial effects can generally be derived from a common framework premised on bacterial growth and kill rate processes. The fundamental differential equation describing bacterial growth and drug-induced killing is:

dN/dt = k₉ʳᵒʷᵗʰ × N - kₖᵢₗₗ(C) × N

where N is the bacterial density, k₉ʳᵒʷᵗʰ is the first-order growth rate constant, and kₖᵢₗₗ(C) is the drug concentration-dependent kill rate, which can be described by various models including the sigmoid Emax model [30].

More sophisticated models may incorporate additional components such as:

- Adaptation phases accounting for initial growth delay

- Subpopulations with different susceptibility profiles

- Post-antibiotic effects

- Immune system contributions to bacterial clearance

Application Protocol: Time-Kill Curve Experiments

Objective: To characterize the time-dependent killing activity of an antimicrobial agent against a target pathogen.

Materials and Reagents:

- Test antimicrobial agent (stock solutions at appropriate concentrations)

- Bacterial strains (reference and clinical isolates)

- Culture media (Mueller-Hinton broth or other appropriate media)

- Sterile flasks or tubes for time-kill experiments

- Water bath or shaking incubator for temperature control

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for serial dilutions

- Agar plates for viable counting

- Colony counter or automated enumeration system

Procedure:

- Preparation: Prepare antibiotic solutions at multiple concentrations (e.g., 0.5×, 1×, 2×, 4×, 8× MIC) in appropriate culture media.

- Inoculation: Add standardized bacterial inoculum (approximately 10⁵-10⁶ CFU/mL) to each antibiotic-containing flask and to growth control flasks (no antibiotic).

- Incubation: Incubate under appropriate conditions with shaking if necessary.

- Sampling: Remove samples at predetermined timepoints (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24 hours) for viable counting.

- Viable Counting: Perform serial dilutions of samples in PBS, plate onto appropriate agar media, incubate, and enumerate colonies.

- Data Collection: Record CFU/mL values for each timepoint and antibiotic concentration.

- Modeling: Fit appropriate mathematical models to the time-kill data using nonlinear regression. Start with a simple growth/kill model and incorporate additional components as needed to describe the data adequately.

Table 3: Time-Kill Curve Characterization of Antimicrobial Activity

| Antibiotic Class | Killing Pattern | Regrowth Potential | PAE Duration | Typical Model Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-lactams | Time-dependent | Common with sub-MIC concentrations | Short (0-2 hours) | Growth rate, maximum kill rate, resistance emergence |

| Aminoglycosides | Concentration-dependent | Less common with adequate Cmax/MIC | Moderate (1-3 hours) | Growth rate, high maximum kill rate, adaptive resistance |

| Fluoroquinolones | Concentration-dependent | Can occur with resistant subpopulations | Prolonged (1-5 hours) | Multi-population model, resistant subpopulation |

| Glycopeptides | Time-dependent | Slow, often observed at 24-48 hours | Short to moderate | Slow bacterial killing, heterogeneous populations |

Integrated PK/PD Modeling Approaches

Integration Methodologies and Applications

Integrated PK/PD modeling combines the mathematical frameworks describing drug exposure (PK) and drug effect (PD) into a unified model that can predict the complete time course of pharmacological response to dosing [21] [22]. For anti-infective agents, these integrated models are particularly valuable for identifying optimal dosing regimens that maximize efficacy while minimizing resistance development [25].

The integration can be accomplished through different approaches:

- Direct Link Models: Where the effect is directly related to the plasma or effect site concentration

- Indirect Response Models: Where the drug acts indirectly by inhibiting the production or stimulating the loss of response mediators

- Transduction Models: Which incorporate delays between plasma concentrations and effects through series of transit compartments

For anti-infective agents, the most common approach involves linking a compartmental PK model with a kill curve PD model, often incorporating an effect compartment to account for hysteresis when necessary [21].

Application Protocol: Developing Integrated PK/PD Models

Objective: To develop an integrated PK/PD model for a novel anti-infective agent using both plasma concentration data and microbial kill curve data.

Materials and Reagents:

- All materials listed in Protocols 2.3 and 4.3

- PK/PD modeling software (e.g., NONMEM, Monolix, Berkeley Madonna)

- Dataset containing both concentration-time and effect-time data

Procedure:

- Data Assembly: Compile a comprehensive dataset containing dose administration times, plasma concentration measurements, and corresponding effect measurements (e.g., bacterial density over time).

- Structural Model Identification:

- Develop the structural PK model based on concentration-time data

- Develop the structural PD model based on effect-concentration relationships

- Select appropriate link model (direct, indirect, effect compartment)

- Stochastic Model Development: Incorporate interindividual variability and residual error models to account for variability in PK and PD parameters.

- Model Fitting: Simultaneously fit all model parameters to the combined PK/PD dataset using appropriate estimation algorithms.

- Model Evaluation: Assess model performance using diagnostic plots, visual predictive checks, and bootstrap analysis.

- Model Simulation: Utilize the validated model to simulate bacterial killing under different dosing regimens and for different bacterial subpopulations.

Diagram 3: Integrated PK/PD Modeling Framework

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Pharmacometric Modeling Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | Mueller-Hinton Broth, Cation-adjusted MH Broth | Support bacterial growth in PD studies | Standardized composition critical for reproducible MIC and time-kill results [29] |

| Analytical Standards | Certified reference standards, Stable isotope-labeled internal standards | Bioanalytical method calibration and quantification | Essential for accurate PK concentration measurements; should be of highest purity |

| Protein Binding Assays | Equilibrium dialysis devices, Ultrafiltration devices | Determination of free drug fraction | Critical for PK/PD correlations as only free drug is pharmacologically active [28] |

| Enzymatic Assays | β-lactamase detection kits, Metabolic activity assays | Assessment of resistance mechanisms and bacterial viability | Complementary to CFU counting for understanding antibacterial mechanisms |

| Animal Disease Models | Murine thigh infection, Lung infection models | In vivo PK/PD correlation | Provide host-pathogen-drug interactions for translational modeling [29] |

| Hollow Fiber Systems | Hollow fiber infection models | Simulation of human PK profiles in vitro | Enable complex multi-dose regimen simulations without animal use [25] |

| Automated Colony Counters | Protocol 3, Scan 1200 | Accurate enumeration of bacterial colonies | Reduce variability in PD endpoint measurements |

The integration of compartmental PK modeling with mechanism-based PD approaches, particularly time-kill curve analysis and sigmoid Emax models, provides a powerful framework for optimizing anti-infective therapy and combating antimicrobial resistance. These modeling approaches enable researchers to characterize complex exposure-response relationships, identify optimal dosing strategies, and predict clinical efficacy based on preclinical data. As antibiotic resistance continues to threaten global health, sophisticated pharmacometric approaches will play an increasingly vital role in accelerating the development of novel anti-infective agents and preserving the efficacy of existing therapeutics through model-informed precision dosing.

Pharmacometric modeling and simulation have become cornerstones of modern anti-infective drug development, providing a quantitative framework to link drug exposure to pharmacological effect. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling integrates mathematical models to describe the complete time course of the dose-response relationship, moving beyond traditional isolated approaches where pharmacokinetics described only plasma concentrations and pharmacodynamics described only the intensity of the response [22]. This integration has proven particularly valuable for optimizing dose regimens for antibacterial and antifungal agents, especially given the expanding crisis of antimicrobial resistance [22] [31]. In the context of a broader thesis on pharmacometric modeling, PK/PD approaches enable more efficient drug development by supporting candidate selection, dose regimen definition, and clinical outcome simulation across all phases of drug development [22].

The fundamental rationale behind PK/PD modeling is to unite the time course of drug concentrations with the resultant effect on pathogens, thereby establishing a robust dose-concentration-response relationship [22]. For anti-infectives, this relationship is uniquely complex as it involves three distinct entities: the host (who receives the drug), the pathogen (which the drug targets), and the drug itself. PK/PD models typically consist of a pharmacokinetic component (often using compartmental models) linked to a pharmacodynamic component that relates drug concentration to antimicrobial effect using mathematical functions such as the sigmoid Emax model [22].

Foundational PK/PD Concepts and Indices

Core PK/PD Parameters and Their Significance

PK/PD modeling for anti-infectives relies on several key parameters that integrate drug exposure with measures of pathogen susceptibility. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) represents the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial that prevents visible growth of a microorganism under standardized conditions and serves as a fundamental measure of drug potency [22] [32]. However, the MIC alone provides limited information as it is a static measure that doesn't account for dynamic concentration-time relationships.

Three primary PK/PD indices have been established to correlate pharmacokinetic parameters with MIC values, each particularly relevant for different classes of antimicrobial agents [33] [34]:

- Area Under the Curve to MIC ratio (AUC/MIC): Integrates both concentration and time aspects of drug exposure, most commonly applied to concentration-dependent antimicrobials like fluoroquinolones and azoles.

- Time Above MIC (%T>MIC): Represents the percentage of a dosing interval that drug concentrations remain above the MIC, particularly critical for time-dependent antimicrobials like β-lactams.

- Peak Concentration to MIC ratio (Cmax/MIC): Relates the maximum drug concentration to the MIC, important for concentration-dependent drugs like aminoglycosides and polyenes.

These indices serve as critical predictors of therapeutic efficacy and form the basis for optimizing dosing strategies across different patient populations and pathogen profiles [34].

Table 1: Key PK/PD Indices and Their Clinical Applications

| PK/PD Index | Definition | Primary Drug Classes | Target Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC/MIC | Area under the concentration-time curve over 24h divided by MIC | Fluoroquinolones, Azoles, Glycopeptides | Variable by drug: e.g., >100-400 for fluoroquinolones |

| %T>MIC | Percentage of dosing interval that concentration exceeds MIC | β-lactams, Carbapenems | 30-70% depending on pathogen and drug |

| Cmax/MIC | Peak concentration divided by MIC | Aminoglycosides, Polyenes | ≥8-10 for optimal efficacy |

Advanced PD Concepts: Resistance Prevention and Combination Therapy

Beyond standard efficacy parameters, advanced PD concepts address the critical issue of antimicrobial resistance. The mutant prevention concentration (MPC) defines the drug concentration that prevents the growth of resistant mutants, while the mutant selection window (MSW) represents the concentration range between MIC and MPC where resistant subpopulations are selectively enriched [34]. Targeting drug concentrations above the MPC through optimized dosing represents a key strategy for suppressing resistance emergence.

For complex infections and multidrug-resistant pathogens, combination therapy leverages PK/PD principles to achieve synergistic effects. The primary methodologies for evaluating combinations include time-kill studies for dynamic assessment and in vitro PK/PD models like the hollow fiber infection model (HFIM) that simulate human pharmacokinetics [23] [32]. These approaches allow researchers to identify combinations that enhance bacterial killing, prevent resistance, and improve clinical outcomes.

Experimental Approaches in PK/PD Research

In Vitro Methodologies

In vitro PK/PD models serve as the initial platform for characterizing antimicrobial pharmacodynamics, ranging from simple static systems to complex dynamic models that simulate human pharmacokinetic profiles [33] [32].

Protocol 3.1.1: Static Time-Kill Curve Assay

- Purpose: To characterize the time- and concentration-dependent antibacterial activity of an antimicrobial agent against a specific pathogen.

- Materials: Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (for bacteria) or RPMI-1640 (for fungi), standardized microbial inoculum (approximately 5×10^5 CFU/mL), antimicrobial stock solutions, sterile tubes or microtiter plates, water bath or incubator.

- Procedure:

- Prepare serial dilutions of the antimicrobial in growth medium to achieve target concentrations (typically 0.25× to 4× MIC).

- Inoculate tubes with standardized microbial suspension.

- Incubate at appropriate temperature (35±2°C for bacteria; 35°C for yeasts).

- Sample at predetermined timepoints (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 hours).

- Perform viable counts by serial dilution and plating on appropriate agar.

- Count colonies after 18-24 hours incubation and calculate CFU/mL.

- Data Analysis: Plot log10 CFU/mL versus time for each concentration. Determine bactericidal activity (≥3-log reduction from initial inoculum) and bacteriostatic activity (<3-log reduction).

Protocol 3.1.2: Hollow Fiber Infection Model (HFIM)

- Purpose: To simulate human pharmacokinetics of antimicrobial agents in vitro and study bacterial killing and resistance emergence over extended periods.

- Materials: Hollow fiber bioreactor system, growth medium, antimicrobial stock solutions, peristaltic pumps, reservoir bottles, standardized microbial inoculum.

- Procedure:

- Load the central reservoir with growth medium containing the antimicrobial at a concentration calculated to simulate human PK profiles.

- Inoculate the extracapillary space with standardized microbial suspension.

- Program the pump system to achieve desired drug elimination half-life through continuous inflow and outflow.

- Sample from the extracapillary space at multiple timepoints over 24-72 hours.

- Perform viable counts and assess for resistance development through subculturing on drug-containing plates.

- Data Analysis: Compare bacterial killing and regrowth patterns across different dosing regimens; model PK/PD relationships using mathematical functions.

Diagram 1: Hollow Fiber Infection Model Workflow

In Vivo Animal Models

Animal PK/PD models bridge the gap between in vitro studies and clinical trials, incorporating host factors such as immunity, tissue penetration, and natural infection progression [33].

Protocol 3.2.1: Murine Thigh Infection Model

- Purpose: To evaluate the in vivo efficacy of antimicrobial regimens against specific pathogens in a standardized localized infection.

- Materials: Immunosuppressed mice (typically neutropenic), bacterial or fungal suspension, antimicrobial solutions for dosing, calipers for thigh measurement, equipment for homogenization and plating.

- Procedure:

- Render mice neutropenic with cyclophosphamide (150 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg administered 4 days and 1 day before infection).

- Inoculate thighs with standardized microbial suspension (typically 10^6-10^7 CFU/thigh).

- Administer antimicrobial treatment according to predefined regimens (varying doses, frequencies, durations).

- Sacrifice animals at predetermined endpoints (typically 24 hours).

- Harvest and homogenize thigh tissues.

- Perform serial dilution and plating for viable counts.

- Data Analysis: Calculate log10 CFU/thigh; determine relationships between PK/PD indices (AUC/MIC, T>MIC) and microbial kill.

Protocol 3.2.2: Murine Pneumonia Model

- Purpose: To evaluate antimicrobial efficacy in a pulmonary infection model, particularly relevant for respiratory pathogens.

- Materials: Mice, bacterial or fungal suspension, inhalation anesthesia apparatus, intratracheal inoculation equipment, antimicrobial solutions.

- Procedure:

- Anesthetize mice with inhaled anesthetic.

- Inoculate via intratracheal instillation with standardized microbial suspension.

- Administer antimicrobial treatments according to predefined regimens.

- Sacrifice animals at predetermined timepoints.

- Harvest lung tissues for homogenization and viable counting or histological analysis.

- Data Analysis: Calculate log10 CFU/lung; correlate with PK/PD indices and lung drug concentrations.

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental PK/PD Models

| Model Type | Key Advantages | Limitations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static Time-Kill | Simple, inexpensive, high throughput | Does not simulate changing concentrations | Initial screening of antimicrobial activity |

| Dynamic HFIM | Simulates human PK, studies resistance | Technically complex, expensive | Regimen optimization, resistance prevention |

| Murine Thigh | Standardized, incorporates host factors | Localized infection, requires immunosuppression | PK/PD index determination, dose fractionation |

| Murine Pneumonia | Clinically relevant infection site | Technically challenging inoculation | Pulmonary infection therapies |