Overcoming Stability Challenges in Antimicrobial Peptide Formulations: From Molecular Design to Clinical Translation

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) represent a promising class of therapeutics to combat the rising tide of antibiotic-resistant infections.

Overcoming Stability Challenges in Antimicrobial Peptide Formulations: From Molecular Design to Clinical Translation

Abstract

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) represent a promising class of therapeutics to combat the rising tide of antibiotic-resistant infections. However, their clinical translation is significantly hampered by inherent stability issues, including susceptibility to proteolytic degradation, short half-life, and low bioavailability. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of contemporary strategies to enhance AMP stability, covering foundational challenges, advanced formulation methodologies like liposomal and nanoparticle systems, optimization techniques including AI-driven design, and the current clinical landscape. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes the latest advances to guide the rational development of stable, efficacious, and clinically viable AMP-based therapeutics.

The Stability Conundrum: Understanding the Core Challenges Plaguing Antimicrobial Peptides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary reasons for the short half-life of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) in biological systems? The short half-life of AMPs is primarily due to two inherent vulnerabilities: proteolytic degradation and rapid renal clearance [1]. AMPs are composed of natural L-amino acids joined by amide bonds, which are susceptible to cleavage by a wide array of proteases and enzymes present in plasma, tissues, and serum [1] [2]. Furthermore, their relatively small size makes them susceptible to rapid filtration and elimination by the kidneys, leading to a short circulation time in vivo [2].

Q2: How does the proteolytic stability of a peptide in serum differ from its stability in whole blood? Peptide stability can vary significantly between different biological fluids. Research shows that peptides are generally degraded faster in serum than in plasma [3]. Surprisingly, peptides are often more stable in fresh whole blood than in serum derived from the same animal [3]. This is because the process of preparing serum activates coagulation factors, which are primarily calcium-dependent serine proteases (e.g., thrombin) that cleave C-terminal to lysine or arginine residues, thereby increasing proteolytic activity [3]. Therefore, stability in commercial serum may not accurately predict in vivo performance.

Q3: What are the most common chemical modifications used to improve AMP stability? Several chemical modification strategies are effectively employed to enhance the metabolic stability of AMPs:

- D-Amino Acid Substitution: Replacing natural L-amino acids with their D-isomers makes the peptide sequence unrecognizable to many proteases [2]. For example, replacing L-Val and L-Pro with D-amino acids in the peptide N6 improved its stability against proteases [2].

- Cyclization: Creating cyclic peptides, either through disulfide bridges or head-to-tail cyclization, makes them more rigid and less accessible to proteases [2]. Marketed AMPs like bacitracin A, daptomycin, and polymyxins are cyclic [2].

- PEGylation: Attaching polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains to the peptide can improve its biocompatibility, increase its effective size to reduce renal clearance, and shield it from proteolytic enzymes [2]. This has been successfully applied to peptides like OM19r-8 and N6NH2 [2].

- Terminal Modification: N-terminal acetylation or C-terminal amidation can block the action of exopeptidases like aminopeptidases and carboxypeptidases [4].

Q4: Beyond chemical modification, what formulation approaches can protect AMPs from degradation? Advanced delivery systems can shield AMPs from the biological environment and provide controlled release:

- Nanoparticles: Encapsulating AMPs in nanoparticles can protect them from proteolytic degradation, enhance their bioavailability, and allow for targeted delivery to the site of infection [5].

- Hydrogels: These networks can act as reservoirs for AMPs, providing a sustained and localized release that minimizes systemic exposure and degradation [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing Instability in Preclinical Models

If your AMP shows promising in vitro activity but fails in in vivo models, follow this diagnostic pathway to identify the root cause.

Problem: The antimicrobial peptide exhibits potent activity in laboratory assays but demonstrates significantly reduced efficacy during in vivo animal studies.

Investigation Procedure:

- Perform an Ex Vivo Stability Assay: Collect blood via cardiac puncture directly into a syringe containing your peptide solution to prevent clotting. Incubate this fresh whole blood at 37°C [3].

- Conduct a Comparative Stability Analysis: In parallel, incubate your peptide in commercially obtained serum and plasma from the same animal species [3].

- Sample and Analyze: Take aliquots from each mixture at set time points (e.g., 0, 10, 30, 60 minutes). Precipitate proteins with trichloroacetic acid (TCA), centrifuge, and analyze the supernatants using Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) to quantify the remaining intact peptide [3].

- Identify Degradation Fragments: Use Mass Spectrometry (MS) to analyze the degradation products from each biological fluid. This will pinpoint the specific cleavage sites within your peptide sequence [3].

Interpretation & Solutions:

- If degradation is slow in fresh blood but fast in commercial serum: The instability is likely linked to proteases activated during the serum clotting process (e.g., thrombin). Consider modifying lysine and arginine residues or using D-amino acid substitutes [3] [2].

- If degradation is rapid across all fluids: Your peptide is broadly susceptible to various proteases. Implement broad-stability strategies like cyclization or PEGylation [2].

- If degradation is minimal but in vivo efficacy is low: The issue may be rapid renal clearance or poor distribution to the target site. Consider PEGylation to increase hydrodynamic size or reformulate using a delivery system for targeted release [5] [2].

Optimizing Peptide Stability Through Design

This guide helps you systematically improve peptide stability through iterative design and testing.

Problem: Your lead AMP candidate is effective against pathogens but is rapidly degraded by proteases, limiting its therapeutic potential.

Optimization Procedure:

- Baseline Stability Profiling: Begin by incubating your lead peptide with specific proteases (e.g., trypsin, chymotrypsin) or in 10-50% serum. Use HPLC and MS to determine the half-life and identify the primary cleavage sites [3] [1].

- Iterative Modification:

- For cleavage near termini: Implement N-terminal acetylation or C-terminal amidation to block exopeptidases [4].

- For cleavage after basic residues (Lys/Arg): Replace L-lysine or L-arginine with D-enantiomers or other cationic, non-proteinogenic amino acids [2].

- For broad, non-specific degradation: Introduce cyclization via disulfide bridges or head-to-tail synthesis to confer conformational rigidity [2]. Alternatively, incorporate synthetic aromatics that provide steric hindrance and enhance helicity through non-covalent π-π interactions [4].

- Functional Validation: After each modification cycle, re-test the peptide's stability using the assays from Step 1. Crucially, confirm that the antimicrobial activity is retained via minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays [2].

- Advanced Validation: Before moving to costly in vivo studies, validate the stability of your optimized peptide in the ex vivo fresh whole blood model described in Section 2.1 [3].

Quantitative Data on Peptide Stability

Table 1: Comparative Half-Life of Peptides in Different Biological Fluids

This table summarizes data on how different model peptides degrade in various media, highlighting the importance of choosing the right stability assay. [3]

| Peptide Family / Name | Sequence (Cleavage Site) | Half-life in Fresh Blood (Ex Vivo) | Half-life in Commercial Serum | Half-life in Commercial Plasma | Key Proteases Involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Api88 | (Proprietary) | ~30 minutes | < 10 minutes | ~60 minutes | Coagulation factors (e.g., Thrombin) |

| Model Peptide A | ...KK↓AR... | > 60 minutes | ~15 minutes | > 60 minutes | Trypsin-like serine proteases |

| Model Peptide B | ...AA↓GP... | > 60 minutes | ~45 minutes | > 60 minutes | Nonspecific proteases |

Table 2: Impact of Chemical Modifications on Peptide Stability and Properties

This table outlines common stabilization strategies and their effects on peptide characteristics. [1] [2] [4]

| Modification Strategy | Mechanism of Stabilization | Effect on Proteolytic Half-Life | Potential Trade-offs / Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-Amino Acid Substitution | Renders peptide unrecognizable to proteases | Increase of several fold | Must verify that target receptor binding is not disrupted |

| Cyclization | Restricts conformational flexibility, shielding cleavage sites | Significant increase | Can be complex synthetically; may affect membrane interaction |

| PEGylation | Shields peptide via steric hindrance; reduces renal clearance | Moderate to significant increase | Can reduce antimicrobial activity; requires optimization of PEG size |

| Terminal Modification (Acetylation/Amidation) | Blocks action of exopeptidases | Moderate increase | Only protects termini; does not prevent endoprotease cleavage |

| Conjugation with Synthetic Aromatics | Provides steric hindrance and enhances α-helicity | Significant increase (as shown in model peptides) | A novel strategy; long-term toxicity profile may be less established |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Peptide Stability

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Pooled Mouse/Human Serum | Provides a complex mix of active proteases for stability screening. | Be aware: Protease composition differs from fresh blood due to coagulation activation [3]. |

| K₂EDTA or Lithium Heparin Plasma | Provides a protease profile closer to circulating blood by inhibiting coagulation. | EDTA chelates Ca²⁺, inhibiting metalloproteases and coagulation factors [3]. |

| Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) | Precipitates proteins and peptides to stop enzymatic reactions in stability assays. | The supernatant contains small peptide fragments for HPLC analysis after neutralization [3]. |

| RP-HPLC System with C18 Column | Separates and quantifies the intact peptide from its degradation products. | The primary tool for determining degradation half-life [3]. |

| Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight (MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS) | Identifies the molecular weights of intact peptides and their degradation fragments to pinpoint cleavage sites. | Crucial for informing rational design and modification strategies [3]. |

| Trypsin, Chymotrypsin, Elastase | Used for targeted stability studies to understand susceptibility to proteases with specific cleavage preferences. | Trypsin cleaves after Lys/Arg; Chymotrypsin after aromatic residues; Elastase after small neutral residues [6]. |

| Synthetic Aromatic Compounds (e.g., NDI) | Conjugated to peptides via disulfide bridges to provide steric hindrance against proteases and enhance helicity. | A tool for non-covalent, structure-based stabilization as described in research [4]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common AMP Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Hemolytic Activity | Excessive peptide hydrophobicity; overly positive charge leading to non-specific membrane disruption. | Reduce hydrophobicity by substituting with less hydrophobic amino acids (e.g., Ala to Gly); Introduce cationic residues like Dap to reduce hemolysis while maintaining activity [7]. | [8] [7] |

| Poor Plasma Stability | Susceptibility to proteolytic degradation by serum proteases. | Introduce disulfide bonds via cysteine residues; Conjugate with mPEG to shield from enzymatic breakdown; Use D-amino acids to create protease-resistant analogs [8] [9]. | [8] [9] |

| Low Antimicrobial Efficacy | Insufficient interaction with bacterial membranes; suboptimal hydrophobicity/charge balance. | Increase net positive charge to enhance binding to anionic bacterial membranes; Optimize hydrophobicity to a "sweet spot" (neither too high nor too low); Utilize hybrid peptide strategy to combine active fragments [9]. | [9] [10] |

| Cytotoxicity to Mammalian Cells | Lack of selectivity for bacterial vs. mammalian cells. | Employ a "Safe-by-Design" approach by incorporating specific residues (e.g., Dap) shown to lower cytotoxicity; Use targeted delivery systems (e.g., nanoparticles) to concentrate peptide at infection site [7] [10]. | [10] [7] |

| Loss of Activity Post-Modification | Structural changes disrupt the active conformation or membrane-binding motif. | When cyclizing or dimerizing, ensure the active face of the peptide remains accessible; For point mutations, use helical wheel projections to predict impact on amphipathicity [8]. | [8] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental cause of the Toxicity-Stability Paradox in Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs)?

The paradox arises because the physicochemical properties that enhance an AMP's antimicrobial efficacy—such as a high net positive charge and appropriate hydrophobicity—are often the same properties that contribute to non-specific interactions with eukaryotic cell membranes (like red blood cells), leading to hemolysis and cytotoxicity [8] [9]. Furthermore, a linear, bioactive structure is often susceptible to rapid proteolytic degradation in plasma, forcing a trade-off between stability and inherent activity [10] [11].

Q2: What are the most effective strategies to reduce the hemolytic activity of a promising AMP?

Two highly effective strategies are:

- Charge Engineering: Substituting lysine with other cationic amino acids like L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid (Dap) has been shown to effectively decrease hemolytic activity while maintaining or even improving antimicrobial potency [7].

- PEGylation: Conjugating the AMP with methoxy polyethylene glycol (mPEG) can significantly shield its hydrophobic regions, reducing non-specific interactions with red blood cell membranes and thereby lowering hemolysis [8].

Q3: How can I improve the plasma stability of my AMP without completely compromising its function?

Introducing structural constraints is a key approach. This includes:

- Cyclization: Creating disulfide bonds through the introduction of cysteine residues can dramatically enhance stability against proteases [8].

- Using D-Amino Acids: Incorporating D-enantiomers of amino acids makes the peptide sequence unrecognizable to many natural proteases, thereby increasing its half-life in biological fluids [9].

- Nano-encapsulation: Formulating AMPs within nanoparticles or hydrogels can protect them from degradation and provide controlled release, improving bioavailability and stability at the infection site [10].

Q4: Are there specific amino acid substitutions known to improve the therapeutic index (TI) of AMPs?

Yes, research indicates that substitutions with certain non-canonical amino acids are beneficial. For instance, in the antimicrobial peptide Polybia-MPII, replacing lysine with L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid (Dap) not only enhanced its stability against tryptic digestion but also effectively decreased its hemolytic activity and cytotoxicity, leading to an overall improved therapeutic index [7].

Q5: What is a key consideration when designing experiments to assess AMP cytotoxicity?

It is critical to use multiple, complementary assays. A common approach is to pair a membrane integrity-based assay (e.g., using a dye like trypan blue or a fluorescent DNA-binding dye like SYTOX Green that penetrates only dead cells) with a metabolic activity assay (e.g., ATP detection) [12]. This helps distinguish between true cytotoxicity and cytostatic effects, providing a more comprehensive safety profile.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Key Quantitative Data on AMP Modifications

Table 2: Impact of Structural Modifications on AMP Properties

| Modification Type | Example / Residue | Effect on Antimicrobial Activity | Effect on Hemolysis | Effect on Plasma Stability | Key Finding / Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Substitution | Lysine (Lys) | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | Control reference [7]. |

| Arginine (Arg) | Improved | No improvement | No improvement | Enhanced activity but poor stability [7]. | |

| Dap (L-2,3-diamino-propionic) | Maintained | Decreased | Improved | Improved therapeutic index and tryptic stability [7]. | |

| Conjugation | mPEG | Decreased | Significantly Reduced | Significantly Improved | Trade-off: stability gained, but intrinsic activity often lowered [8]. |

| Structural | Cysteine (for cyclization) | Variable | Increased (due to hydrophobicity) | Enhanced conspicuously | Stability is improved, but increased hydrophobicity can raise hemolysis [8]. |

| Sequence Alteration | Altered sequence (same composition) | Little impact | Little impact | Little impact | Changing order of amino acids alone is insufficient [8]. |

Detailed Methodologies

Protocol 1: Assessing Hemolytic Activity This protocol measures the damage AMPs cause to red blood cells, a key indicator of toxicity.

- Preparation of RBCs: Collect fresh human or animal (e.g., sheep) blood in heparinized tubes. Centrifuge at 1,000-2,000 × g for 10 minutes. Remove plasma and buffy coat. Wash the pelleted red blood cells three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Peptide Incubation: Prepare a 2-4% (v/v) suspension of the washed RBCs in PBS. Incubate this suspension with a serial dilution of your AMP (typical concentration range 1-256 µg/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C. Include controls: PBS only (0% hemolysis) and 1% Triton X-100 (100% hemolysis).

- Measurement: After incubation, centrifuge the samples. Transfer the supernatant to a 96-well plate and measure the absorbance of released hemoglobin at 540 nm using a plate reader.

- Calculation: Calculate the percentage of hemolysis for each peptide concentration:

% Hemolysis = [(Abs_sample - Abs_PBS) / (Abs_TritonX - Abs_PBS)] × 100. The HC50 (concentration causing 50% hemolysis) is a standard metric for comparison [8] [7].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Tryptic Stability (Plasma Stability) This protocol tests an AMP's resistance to protease degradation, simulating in vivo conditions.

- Reaction Setup: Dissolve the AMP in a suitable buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, pH 7.4-8.0). Add trypsin to the solution at a specific enzyme-to-substrate ratio (e.g., 1:20 to 1:50 w/w). Incubate the mixture at 37°C.

- Sampling: Withdraw aliquots at regular time intervals (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes). Immediately stop the enzymatic reaction by adding a stop solution, such as trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) or by heating at 95°C for 5 minutes.

- Analysis: Analyze the samples using Reverse-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC). Monitor the disappearance of the intact peptide peak over time.

- Data Interpretation: Calculate the half-life (t1/2) of the peptide. A longer half-life indicates superior stability. Studies have shown that modifications like incorporating Dap can significantly slow the degradation rate compared to the native peptide [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| SYTOX Green / Propidium Iodide | Fluorescent, membrane-impermeant DNA dyes that selectively enter dead cells with compromised membranes, used to quantify cytotoxicity [12]. | Distinguishing live from dead cells in a cytotoxicity assay via fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry. |

| Trypan Blue | A vital dye excluded by live cells but taken up by dead cells, allowing for manual counting of cell viability [12]. | Quick and routine assessment of cell viability and concentration before seeding for an experiment. |

| mPEG (methoxy PEG) | A polymer conjugated to AMPs to shield them from proteolytic enzymes and reduce non-specific binding to host cells, thereby improving stability and reducing toxicity [8]. | Creating a PEGylated AMP derivative to test for improved plasma stability and reduced hemolysis in serum assays. |

| Cysteine | An amino acid used to introduce disulfide bonds into the peptide structure, conferring rigidity and resistance to proteolysis [8]. | Designing a cyclic AMP analog to test the hypothesis that constrained structures have enhanced stability. |

| Non-Canonical Amino Acids (Dap, Dab) | Synthetic counterparts of lysine that can be incorporated during peptide synthesis to fine-tune charge, hydrophobicity, and stability without altering the sequence length drastically [7]. | Systematically replacing lysine residues in a parent AMP to identify analogs with a lower hemolytic profile. |

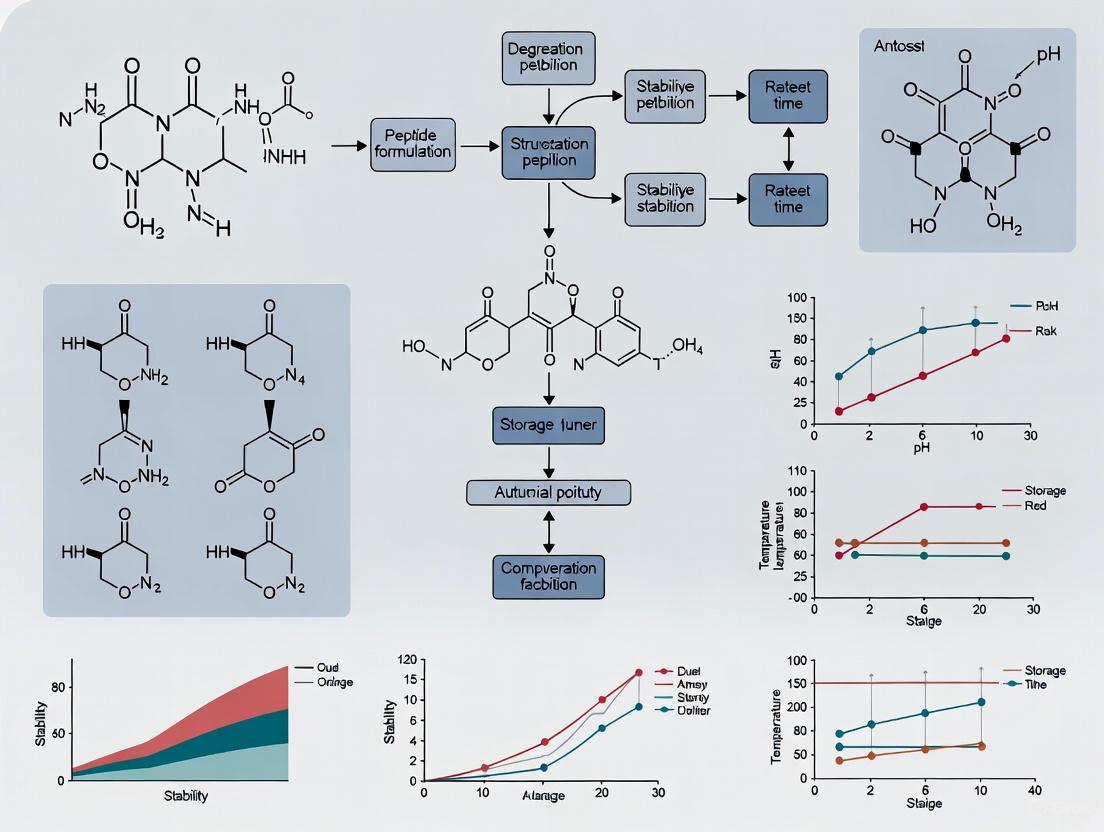

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

AMP Optimization Workflow

AMP Optimization Workflow

Toxicity-Stability Paradox Mechanism

Paradox Mechanism & Resolution

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary factors that limit the systemic bioavailability of Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs)? The systemic bioavailability of AMPs is limited by a combination of factors, including susceptibility to proteolytic degradation by host proteases in serum and blood cells, cytotoxicity (particularly hemolytic activity), rapid systemic clearance, and poor permeability across biological membranes [10] [13] [11]. These inherent limitations often result in a short half-life and loss of activity before the peptide reaches its microbial target.

FAQ 2: How can the stability of AMPs against proteolytic degradation be improved? A common and effective strategy is amino acid substitution. This involves partially or wholly replacing L-amino acids in the peptide sequence with their D-amino acid counterparts [14]. Such modifications make the AMP resistant to protease degradation, as demonstrated by peptides maintaining their activity after incubation with trypsin and fetal calf serum, whereas their all-L-amino acid counterparts were degraded [14]. Other strategies include chemical modification (e.g., cyclization, N-methylation) and encapsulation within protective delivery systems [15] [10].

FAQ 3: What is the significance of "bioavailability as a microbial system property" in environmental bioremediation? This concept emphasizes that bioavailability is not just a chemical property but is fundamentally shaped by the biological system, including the physiology, ecology, and mobility of the degrading microorganisms [16]. In contexts like biodegradation of pollutants, bioavailability depends on microbial processes such as chemotaxis, production of biosurfactants, and the formation of transport networks (e.g., fungal mycelia), which enhance access to substrates [16]. This ecological perspective is crucial for predicting and enhancing bioremediation success.

FAQ 4: Which delivery systems show promise for enhancing AMP bioavailability and targeted delivery? Several advanced delivery systems are being investigated to overcome bioavailability hurdles:

- Nanoparticles: Inorganic (e.g., gold, silica) and organic (e.g., liposomes, micelles) nanoparticles can protect AMPs from degradation and reduce toxicity [15] [10].

- Hydrogels: These networks allow for controlled release of AMPs at the site of infection, such as in wound dressings, improving local bioavailability [15] [10].

- Targeted Systems: Some strategies involve conjugating AMPs to targeting moieties or designing systems that respond to specific environmental triggers (e.g., pH) at the infection site, enabling precise delivery [15].

FAQ 5: Beyond microbial membranes, what other mechanisms contribute to AMP activity? While many AMPs act by disrupting microbial membranes (membrane-targeting), a significant number exert their effects through non-membrane-targeting mechanisms [10]. These include:

- Inhibition of cell wall synthesis by binding to essential components like lipid II [10].

- Intracellular targeting of vital processes such as nucleic acid synthesis (e.g., indolicidin), protein folding, and enzyme activity [10] [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Rapid Loss of Antimicrobial Activity in Biological Fluids

Potential Cause: Proteolytic degradation of the AMP by proteases present in serum, plasma, or host cell cytosols [14] [13].

Solutions and Experimental Protocols:

Solution A: Incorporate D-Amino Acids

- Principle: Proteases are stereospecific and primarily target L-amino acids. Substituting with D-isomers confers resistance.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Synthesis: Synthesize the parent all-L-amino acid peptide (L-peptide) and one or more variants with partial or complete D-amino acid substitution (D-peptide, All-D-peptide) [14].

- Stability Assay:

- Incubate each peptide (e.g., at 20 µM) with the biological fluid of interest (e.g., 2% serum in PBS) or with washed human erythrocyte cytosolic extracts at 37°C with agitation [14] [13].

- Withdraw samples at various time points (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 120 minutes).

- Analyze samples via reversed-phase HPLC. Monitor the disappearance of the parent peptide peak and the emergence of degradation fragments [13].

- Use MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to identify the cleavage products [13].

- Activity Validation: Confirm that the D-amino acid substituted peptides retain antimicrobial activity against target microbes using a standard MIC (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) or killing assay [14].

Solution B: Utilize Protective Delivery Systems

- Principle: Encapsulate the AMP within a carrier that acts as a physical barrier against proteases.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Formulation: Formulate the AMP into a delivery system such as a liposome, polymeric nanoparticle (e.g., PLGA), or hydrogel [15] [10].

- In Vitro Release and Stability:

- Incubate the free AMP and the AMP-loaded formulation in serum or a protease solution.

- At predetermined time points, separate the released/degraded fraction (e.g., via centrifugation or filtration).

- Measure the intact AMP content using HPLC or a bioassay to compare the stability profile of the formulated vs. free AMP.

The following workflow outlines the core experimental strategies for troubleshooting AMP stability and cytotoxicity:

Problem 2: Unacceptable Cytotoxicity (e.g., Hemolysis) at Therapeutic Concentrations

Potential Cause: The inherent amphipathicity and cationic charge that enable AMPs to disrupt microbial membranes can also cause non-specific lysis of host cells, particularly red blood cells [11] [17].

Solutions and Experimental Protocols:

Solution A: Optimize Peptide Sequence

- Principle: Systematically modify the peptide's physicochemical properties (e.g., hydrophobicity, charge, helicity) to increase its therapeutic index (selectivity for microbes vs. host cells).

- Experimental Protocol:

- Design: Create a library of peptide analogs with variations in key parameters. For instance, reduce overall hydrophobicity or introduce proline residues to disrupt alpha-helical structure.

- Hemolysis Assay:

- Prepare a suspension of fresh human or animal red blood cells (RBCs) in PBS [13].

- Incubate the RBCs with a range of peptide concentrations (and a positive control like Triton X-100 for 100% lysis, and a negative PBS control for 0% lysis) for a set time (e.g., 1 hour) at 37°C.

- Centrifuge the samples and measure the hemoglobin release in the supernatant by absorbance at 540 nm.

- Calculate the percentage hemolysis and determine the HC50 (concentration causing 50% hemolysis). The goal is to significantly increase the HC50 relative to the MIC [11].

Solution B: Formulate with Liposomes

- Principle: Encapsulation in liposomes can shield the AMP from direct contact with host cells until it reaches the target site, thereby reducing systemic cytotoxicity.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Formulation: Prepare liposomes (e.g., from phosphatidylcholine/cholesterol) containing the AMP using a method like thin-film hydration or extrusion.

- Cytotoxicity Testing:

- Perform the hemolysis assay as described above, comparing free AMP with liposome-encapsulated AMP.

- Additionally, test cytotoxicity against other mammalian cell lines (e.g., HEK293) using assays like MTT or LDH release.

- Confirm that the formulation retains antimicrobial efficacy in a co-culture or infection model.

Problem 3: Low Bioavailability at the Specific Site of Infection

Potential Cause: The AMP is distributed systemically but fails to accumulate or remain active at the required local site due to non-specific distribution, clearance, or an unfavorable microenvironment [15] [18] [16].

Solutions and Experimental Protocols:

Solution A: Develop Targeted Delivery Systems

- Principle: Conjugate the AMP or its carrier to ligands (e.g., antibodies, sugars) that bind specifically to receptors at the infection site, such as on microbial surfaces or inflamed host tissues [15].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Conjugation and Formulation: Chemically conjugate the targeting moiety to the AMP or the surface of a nanoparticle carrier.

- In Vitro Binding Test:

- Use techniques like surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or fluorescence microscopy to demonstrate enhanced binding of the targeted formulation to the target microbes or relevant cells, compared to a non-targeted control.

- In Vivo Validation:

- Use an animal model of infection. Administer the targeted and non-targeted formulations and, after a period, quantify the AMP concentration at the infection site and non-target organs (e.g., via HPLC-MS or fluorescence imaging) to demonstrate improved targeting and retention.

Solution B: Engineer Stimuli-Responsive Release

- Principle: Design a delivery system that releases its AMP payload in response to stimuli unique to the infection site, such as low pH, specific enzymes (e.g., lipases, hyaluronidases), or elevated lactate levels [15].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Formulate Responsive Carrier: Create a nanoparticle or hydrogel that degrades or changes structure under the specific stimulus (e.g., a pH-sensitive polymer or an enzyme-cleavable cross-linker).

- In Vitro Release Study:

- Place the AMP-loaded formulation in release buffers mimicking physiological (pH 7.4) and pathological (e.g., pH 5.5-6.5) conditions, or in the presence of the target enzyme.

- Sample the release medium over time and quantify the released AMP. The system should show minimal release under normal conditions and triggered release under pathological conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents and materials for addressing AMP bioavailability challenges.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Benefit | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| D-Amino Acids | Confers resistance to proteolytic degradation by host proteases, thereby increasing peptide stability and half-life [14]. | Synthesis of stable AMP analogs for in vivo applications. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Used in in vitro assays to confirm the role of proteolysis in AMP inactivation and to stabilize peptides during experimental processing [14]. | Added to serum or cell lysate incubations to protect the AMP. |

| Human Erythrocytes | Critical for assessing hemolytic activity (cytotoxicity) and for studying host cell-associated AMP degradation via cytosolic proteases [13]. | Hemolysis assays; preparation of cytosolic extracts for stability testing. |

| Liposome Formulation Kits | Provide a ready-to-use system for encapsulating AMPs, which can reduce cytotoxicity and protect the peptide from degradation [15] [10]. | Creating nanoparticle-based delivery systems for in vivo studies. |

| Cytosolic Extracts | Used to directly screen for susceptibility to intracellular proteases present in host cells, a key degradation pathway beyond serum proteases [13]. | In vitro stability assays under conditions mimicking intracellular environment. |

Table 2: Quantitative data on the effect of D-amino acid substitutions on AMP stability and activity. Data adapted from [14].

| Peptide Type | Sequence (Example) | Stability in Trypsin | Stability in Fetal Calf Serum | Antimicrobial Activity Post-Serum Incubation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All L-amino acid (L-peptide) | GRRGRRGRRGRR | Susceptible (Degraded) | Susceptible (Activity Lost) | Low/None |

| Partial D-amino acid (D-peptide) | GrRGRrGRrGRR (lowercase = D-form) | Resistant | Partially Resistant | Partially Retained |

| All D-amino acid (AD-peptide) | grrgrrgrrgrr (all lowercase = D-form) | Resistant | Resistant | Fully Retained |

The relationship between AMP properties, optimization strategies, and the resulting bioavailability outcomes can be visualized as follows:

Economic and Manufacturing Barriers in Large-Scale Production

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary economic challenges in scaling up Antimicrobial Peptide (AMP) production? The high cost of AMP development and manufacturing is a major barrier to their widespread clinical application. These costs are driven by complex synthesis and purification processes, low yields from natural extraction, and the expensive raw materials required for production. Furthermore, the inherent instability of peptides necessitates costly formulation technologies to ensure sufficient shelf-life and efficacy, making large-scale production economically challenging [11] [19].

FAQ 2: Why are AMPs inherently unstable and how does this impact manufacturing? AMPs face significant stability issues that complicate their manufacturing and storage. They are susceptible to proteolysis (degradation by enzymes), physical instability like aggregation, and chemical instability such as deamidation and oxidation. These undesirable properties lead to a short half-life, low bioavailability, and potential cytotoxicity, which severely limit their clinical application. Overcoming these instabilities requires advanced formulation or delivery systems, adding complexity and cost to the manufacturing process [15] [10] [19].

FAQ 3: What formulation strategies can mitigate the instability of AMPs during storage and delivery? Advanced drug delivery systems are being developed to protect AMPs from degradation and enhance their stability. These include:

- Nanocarriers: Systems like liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and micelles encapsulate AMPs, shielding them from proteolytic enzymes and enabling controlled release at the target site [15] [19].

- Hydrogels: These networks can entrap AMPs and provide a sustained release profile, which is particularly useful for topical applications like wound healing [15].

- Chemical Conjugation: Attaching AMPs to polymers or other molecules can improve their stability and pharmacokinetic profile [15].

FAQ 4: How can production costs be reduced for AMPs? Several approaches can help manage the high production costs of AMPs:

- Heterologous Expression: Using engineered microorganisms to produce AMPs can be more cost-effective than chemical synthesis or extraction from natural sources [19].

- Process Optimization: Implementing smart manufacturing technologies and leveraging economies of scale can improve production efficiency and output [20].

- Structural Optimization: Designing shorter or more stable peptide analogs (e.g., incorporating D-amino acids) can reduce synthesis costs and improve the peptide's stability, thereby lowering downstream processing expenses [21] [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Yield or High Cost in Production

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low yield from natural source extraction. | Natural AMPs are often found in complex biological matrices in low quantities. | Shift to synthetic production methods like solid-phase peptide synthesis or recombinant expression in bacterial/yeast systems [11] [19]. |

| High raw material costs for synthesis. | Use of expensive protected amino acids and coupling reagents. | Optimize synthesis protocols and scale up purchasing to benefit from bulk pricing economies [20] [19]. |

| Inefficient purification process. | Multiple chromatography steps are needed to achieve pharmaceutical-grade purity. | Explore single-step or platform purification methods and invest in continuous manufacturing technology to improve efficiency [22]. |

Problem 2: Peptide Instability and Aggregation

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Peptide aggregates in solution during storage. | Exposure to stress conditions like elevated temperature, pH shifts, or mechanical shear forces [23]. | Reformulate with stabilizers such as sucrose, mannitol, or surfactants (e.g., polysorbate) to suppress molecular interactions [23]. |

| Loss of antimicrobial activity over time. | Chemical degradation (e.g., deamidation or oxidation of amino acids) [23]. | Modify buffer conditions (pH, ionic strength) and consider lyophilization (freeze-drying) for long-term storage. Use inert gas headspace to prevent oxidation [10]. |

| Short half-life in vivo. | Susceptibility to proteolysis by serum proteases [10]. | Incorporate AMPs into a delivery system like nanoparticles or liposomes to protect them from enzymatic degradation [15] [19]. |

Problem 3: Cytotoxicity (e.g., Hemolysis)

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| AMP causes red blood cell lysis (hemolysis). | The peptide's hydrophobicity and cationic charge lead to non-selective interaction with mammalian cell membranes [11] [10]. | Use structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies to optimize the peptide sequence. Reduce overall hydrophobicity or introduce D-amino acids to enhance selectivity for bacterial membranes [11]. |

| Cytotoxicity observed in cell-based assays. | Explore targeted delivery systems (e.g., with surface ligands) to concentrate the AMP at the site of infection and reduce systemic exposure [15]. |

Experimental Data and Protocols

Key Stability and Formulation Data

The data below summarizes common challenges and formulation strategies for AMPs, derived from recent research.

Table 1: Common AMP Instabilities and Mitigation Strategies

| Instability Type | Impact on AMP | Formulation Strategy | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteolytic Degradation | Shortens half-life, reduces bioavailability [10]. | Encapsulation in nanoparticles (e.g., PLGA, gold) [15]. | Enhanced stability in serum; prolonged activity [15] [19]. |

| Aggregation | Loss of activity, increased immunogenicity [23]. | Addition of stabilizers (sucrose, surfactants) [23]. | Improved shelf-life and reduced particle formation. |

| Cytotoxicity | Hemolysis, nephrotoxicity [19]. | Sequence modification (e.g., cyclization) [21]. | Reduced hemolysis while retaining antimicrobial activity [21]. |

| Rapid Clearance | Inefficient dosing, requires frequent administration [15]. | PEGylation or fusion with albumin-binding domains [15]. | Increased circulation half-life [15]. |

Essential Experimental Protocol: Evaluating AMP Stability in Formulation

This protocol is used to assess the physical and chemical stability of an AMP in a chosen formulation under stress conditions.

Protocol Title: Forced Degradation Study for AMP Formulation Screening

1. Objective: To evaluate the stability of an AMP under various stress conditions (heat, light, agitation, pH) to identify the optimal formulation for long-term storage.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Purified AMP

- Candidate formulations (e.g., buffers with different excipients)

- HPLC vials and system with UV/VIS or MS detector

- Thermostated water baths or stability chambers

- Centrifuge

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Sample Preparation. Prepare identical aliquots of the AMP in each candidate formulation.

- Step 2: Stress Application. Subject the aliquots to different stress conditions:

- Thermal Stress: Incubate at 4°C (refrigerator control), 25°C (room temperature), and 40°C (accelerated testing) for 1-4 weeks [23].

- Agitation Stress: Place samples on an orbital shaker for 24-48 hours to simulate transportation forces [23].

- pH Stress: Incubate samples at a range of pH values (e.g., 3, 7, 9) for a set period.

- Step 3: Analysis. At predetermined time points, analyze samples by:

- HPLC: To quantify the percentage of intact AMP remaining and identify degradation peaks [23].

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): To characterize the chemical nature of the degradation products (e.g., deamidation, oxidation) [23].

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): To monitor for aggregation and particle size changes.

4. Data Interpretation: The formulation that retains the highest percentage of intact AMP with the lowest levels of aggregates and degradation products across all stress conditions is considered the most stable and should be selected for further development.

Workflow Diagram: AMP Stability Optimization Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for AMP Formulation and Stability Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Liposomes (e.g., DPPC, Cholesterol) | Versatile nanocarriers for encapsulating AMPs to reduce toxicity and protect against protease degradation [15] [19]. |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles (e.g., PLGA) | Biodegradable particles for sustained release of AMPs, improving pharmacokinetics and bioavailability [19]. |

| Hydrogels (e.g., Chitosan, Alginate) | 3D polymer networks for topical delivery of AMPs, providing a moist wound-healing environment and controlled release [15]. |

| Amino Acids (Fmoc/Derived) | Building blocks for solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) of native or modified AMP sequences [19]. |

| Stabilizers (Sucrose, Trehalose) | Excipients that protect AMPs from aggregation and surface-induced denaturation during storage and lyophilization [23]. |

| Surfactants (Polysorbate 20/80) | Agents that minimize adsorption to containers and reduce shear-induced aggregation during manufacturing [23]. |

Advanced Delivery Systems and Formulation Strategies for Enhanced Stability

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Encapsulation Efficiency

Problem: The percentage of successfully encapsulated antimicrobial peptide (AMP) within liposomes is unacceptably low, leading to wasted API and compromised therapeutic potential.

Solutions:

- For Hydrophilic AMPs (e.g., LL-37): Utilize techniques that maximize the aqueous internal volume of liposomes. The Freezing, Annealing, and Thawing (FAT) method is highly effective, as the freezing step disrupts lamellae and promotes the formation of larger vesicles with greater aqueous space, resulting in higher encapsulation efficiency for water-soluble compounds [24].

- For Hydrophobic AMPs: Employ the Reverse-Phase Evaporation (REV) method. This technique is favorable for lipophilic compounds as it creates a environment where the antibiotic can partition into the forming lipid bilayers, leading to improved encapsulation [24].

- Optimize the Lipid-to-Drug Ratio: A poorly balanced ratio can lead to drug crystallization or leakage. Use Design of Experiments (DoE) to systematically identify the optimal molar ratio for your specific AMP, ensuring sufficient lipid is present to encapsulate the drug without excessive waste [25].

- Implement Remote Loading: For weakly basic amphipathic peptides, establish a transmembrane pH or ion gradient (e.g., ammonium sulfate). This "active loading" technique drives the uncharged drug across the bilayer, where it becomes ionized and trapped, achieving efficiencies over 90% [25].

Poor Physical Stability and Drug Leakage

Problem: Liposomes aggregate, fuse, or leak their encapsulated AMP payload during storage or in physiological media, reducing shelf-life and efficacy.

Solutions:

- Modulate Membrane Rigidity: Incorporate cholesterol (up to 50 mol%) into the phospholipid bilayer. Cholesterol condenses the lipid packing, reduces membrane fluidity, and decreases permeability to water-soluble molecules, thereby minimizing passive leakage [26] [25].

- Select High-Tm Lipids: Use saturated phospholipids with high gel-to-liquid crystalline phase transition temperatures (Tm), such as DSPC. These lipids form more rigid and stable bilayers at physiological temperatures [25].

- Enhance Electrosteric Stabilization:

- Surface Charge: Incorporate charged lipids (e.g., DMPG for negative, DPTAP for positive) to increase the zeta potential (typically >|±30| mV), preventing aggregation via electrostatic repulsion [27] [28].

- PEGylation: Graft polyethylene glycol (PEG) onto the liposome surface to create a "stealth" effect. The hydrated PEG layer sterically inhibits aggregation and opsonization, prolonging circulation time and enhancing stability [29] [25].

- Apply Protective Coatings: For oral delivery, use a dual-coating system with biopolymers like pectin and whey protein isolate (WPI). The polyelectrolyte layers protect the liposome from degradation in the gastrointestinal tract and provide controlled release [28].

- Utilize Lyophilization: Add cryoprotectants like trehalose and perform freeze-drying to create a stable solid powder. This process removes water and prevents lipid bilayer degradation, vastly extending shelf-life [26] [30].

Inefficient Targeting and Cellular Uptake

Problem: Liposomes fail to deliver AMPs effectively to the target site (e.g., intracellular M. tuberculosis), limiting antimicrobial efficacy.

Solutions:

- Create Ligand-Mediated "Stealth" Liposomes: Conjugate target-specific ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides, sugars) to the liposome surface, often via a PEG spacer. This "molecular homing" allows for precise targeting of infected cells or tissues, minimizing off-target effects [31].

- Leverage the Lymphatic System: Design formulations that preferentially utilize the lymphatic system for distribution. This natural detour bypasses first-pass metabolism in the liver, reduces systemic toxicity, and provides a mechanism for prolonged release [31].

- Develop Stimuli-Responsive Liposomes: Use lipids or polymers that change structure in response to specific triggers at the infection site, such as lower pH or specific enzymes. This "intelligent" design ensures the AMP is released primarily at the target site [29] [31].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most critical factor in choosing a liposome preparation method for my antimicrobial peptide? The hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity of your peptide is the primary deciding factor. For hydrophilic AMPs like Vancomycin hydrochloride, methods that maximize aqueous volume (e.g., FAT) are superior. For hydrophobic AMPs like Rifampin, solvent-based methods like Reverse-Phase Evaporation (REV) are more effective. For moderate lipophilicity, techniques like thin film hydration can be suitable, but efficiency must be carefully evaluated [24].

Q2: How can I protect my liposomal formulation from degradation by gastrointestinal enzymes and bile salts? Applying a dual-coating of food-grade biopolymers, such as pectin and whey protein isolate (WPI), has been proven effective. The polyelectrolyte complex formed on the liposome surface acts as a physical barrier, shielding it from proteolytic enzymes and detergent-like bile salts, thereby improving stability for oral delivery [28].

Q3: My liposomes are forming aggregates during storage. How can I prevent this? Aggregation is often a sign of insufficient surface charge or steric hindrance. To prevent this:

- Increase Zeta Potential: Incorporate charged lipids to achieve a zeta potential above |±30| mV, which provides strong electrostatic repulsion between vesicles [27].

- PEGylate: Use PEGylated lipids to create a steric barrier that prevents vesicles from coming close enough to aggregate [29].

- Control Size: Ensure a narrow, uniform particle size distribution via extrusion or microfluidics, as polydisperse samples are more prone to aggregation [25].

Q4: What are the best analytical methods to accurately determine encapsulation efficiency? The choice of method is critical, as some can introduce significant bias. Ultrafiltration followed by bursting the liposomes with methanol is a recommended method for minimal bias. Techniques that rely on dialysis or simple centrifugation can lead to underestimation or overestimation of the encapsulated drug due to non-encapsulated drug binding or incomplete separation [24].

Q5: Can liposomal encapsulation really improve the biocompatibility of antimicrobial peptides like LL-37? Yes. Studies have demonstrated that encapsulating cationic AMPs like LL-37 and IDR-1018 in liposomes (e.g., based on soy lecithin) can significantly reduce their cytotoxicity against human cells (e.g., macrophages, epithelial cells) while maintaining their potent antimicrobial activity against pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis [32].

Quantitative Data for Formulation Optimization

Table 1: Impact of Preparation Method on Encapsulation Performance for Different Antibiotics

Table based on data from [24]

| Antibiotic | Hydrophilicity | Preparation Method | Encapsulation Efficiency (%) | Mass Yield (%) | Key Takeaway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin HCl | High | FAT | 33.4 ± 3 | 93.4 ± 7 | Best mass yield, suitable for hydrophilic drugs. |

| Reverse-Phase Evaporation | 39.4 | <50 | Higher efficiency but poor yield; significant API loss. | ||

| Teicoplanin | Moderate | Reverse-Phase Evaporation | ~74 (Max) | 93.4 ± 3.4 | Optimal method for moderately lipophilic drugs. |

| Rifampin | High (Lipophilic) | Reverse-Phase Evaporation | ~15.5 (Max) | 79.5 ± 3 | Optimal method for highly hydrophobic drugs. |

| Thin Film | 0 | <10 | Unsuitable for this hydrophobic drug. |

Table 2: Lipid Composition and Its Impact on Critical Quality Attributes

Data synthesized from [26] [31] [25]

| Lipid Component | Function | Impact on Liposome Properties | Recommended Use | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated Phospholipids (e.g., DSPC, DPPC) | Forms main bilayer structure. | ↑ Rigidity, ↑ Tm, ↑ Stability, ↓ Permeability. | Core lipid for stable formulations; high-Tm lipids for reduced leakage. | ||

| Cholesterol | Membrane modulator. | ↑ Rigidity, ↓ Fluidity, ↓ Permeability, ↑ Stability against aggregation. | 30-50 mol% to enhance mechanical stability and drug retention. | ||

| Charged Lipids (e.g., DMPG, DPTAP) | Confers surface charge. | ↑ Zeta Potential, ↑ Electrostatic Stability, prevents aggregation. | 5-20 mol% to achieve zeta potential > | ±30 | mV. |

| PEGylated Lipids | Creates steric shield. | ↑ Circulating half-life, ↑ Steric stability, ↓ RES uptake. | 1-10 mol% for "stealth" properties and enhanced stability in biological fluids. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Freezing, Annealing, and Thawing (FAT) for Hydrophilic Peptides

Adapted from [24]

Objective: To encapsulate hydrophilic antimicrobial peptides with high efficiency by creating large unilamellar vesicles with maximized aqueous volume.

Materials:

- Lipids: DPPC, Cholesterol (3:1 molar ratio)

- Aqueous phase: Buffer containing the hydrophilic AMP (e.g., Vancomycin HCl)

- Equipment: Rotary evaporator, liquid nitrogen or -80°C freezer, water bath, extruder.

Procedure:

- Thin Film Formation: Dissolve the lipid mixture in chloroform in a round-bottom flask. Remove the organic solvent using a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure to form a thin, uniform lipid film on the flask walls.

- Primary Hydration: Hydrate the dry lipid film with the aqueous solution containing the AMP above the phase transition temperature (Tm) of the lipids (e.g., 50°C for DPPC) with vigorous stirring for 1 hour. This will form multilamellar vesicles (MLVs).

- Freezing and Thawing: Subject the MLV suspension to 5-10 rapid cycles of freezing in liquid nitrogen (or -80°C) and complete thawing in a warm water bath (above Tm).

- Extrusion: Pass the FAT-treated suspension through polycarbonate membranes of defined pore size (e.g., 100-200 nm) using an extruder for 10-20 passes to homogenize the vesicle size and reduce lamellarity, forming oligo- or unilamellar vesicles.

- Purification: Purify the resulting liposomes from non-encapsulated AMP using gel filtration chromatography or dialysis.

Protocol 2: Dual-Coating of Liposomes for Enhanced GI Stability

Adapted from [28]

Objective: To coat liposomes with layers of pectin and whey protein to protect against gastrointestinal degradation and enable controlled release.

Materials:

- Pre-formed liposomes (e.g., anionic liposomes from DMPC/DMPG)

- Pectin solution (e.g., 0.1-0.5% w/w in buffer)

- Whey Protein Isolate (WPI) solution (e.g., 1-2% w/w in buffer)

Procedure:

- First Layer Coating (Pectin): Under constant mild stirring, add the pectin solution dropwise to the liposome suspension. Continue stirring for 30-60 minutes to allow the anionic pectin to adsorb onto the cationic or anionic liposome surface via electrostatic and weak interactions.

- Second Layer Coating (Whey Protein): Similarly, add the WPI solution dropwise to the pectin-coated liposome suspension. Stir for an additional 30-60 minutes to allow the formation of a secondary layer stabilized by ionic interactions.

- Characterization: Confirm successful coating by measuring the change in zeta potential after each layer addition and by using techniques like FTIR and TEM. Perform in vitro release studies in simulated gastric and intestinal fluids to validate the protective effect.

Workflow and Mechanism Diagrams

Diagram 1: Liposome Formulation Optimization Workflow

Diagram Title: Liposome Formulation Decision Workflow

Diagram 2: Dual-Coated Liposome Protection Mechanism

Diagram Title: Protective Mechanism of Dual-Coated Liposomes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Liposomal Formulation Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Rationale | Example Application in AMP Research |

|---|---|---|

| Soy Lecithin | Natural, food-grade phospholipid mixture; forms the primary liposome bilayer. | Base lipid for creating biocompatible, clinically translatable formulations for peptides like LL-37 [32]. |

| High-Tm Phospholipids (e.g., DSPC, DPPC) | Synthetic saturated lipids; provide a rigid, stable bilayer with low passive permeability. | Core component for formulations requiring high drug retention and long-term stability [25]. |

| Cholesterol | Membrane stabilizer; inserts into the bilayer to reduce fluidity and prevent drug leakage. | Essential additive (30-50 mol%) in most formulations to enhance mechanical stability [26] [25]. |

| PEGylated Lipids (e.g., DSPE-PEG) | Steric stabilizer; creates a hydrophilic corona that reduces opsonization and extends circulation half-life. | Key for creating "stealth" liposomes that evade the immune system for targeted delivery [29] [25]. |

| Pectin & Whey Protein Isolate (WPI) | Biopolymer coating materials; form a protective polyelectrolyte shell via layer-by-layer deposition. | Used to create dual-coated liposomes that resist enzymatic degradation and bile salts in the GI tract [28]. |

| Ammonium Sulfate | Gradient agent; used in remote loading to create a transmembrane pH gradient for active drug encapsulation. | Enables high encapsulation efficiency (>90%) for weakly basic amphipathic compounds [25]. |

| Trehalose | Cryoprotectant; protects liposome integrity during the freeze-drying process by forming a glassy matrix. | Added before lyophilization to ensure long-term shelf stability and easy reconstitution [26] [30]. |

FAQs: Nanoparticle Formulation for Antimicrobial Peptide (AMP) Delivery

Q1: What are the main strategies to improve the circulation time of nanoparticle-based AMP carriers?

A1: The primary strategies involve surface functionalization to create "stealth" nanoparticles and the use of biomimetic coatings.

- PEGylation: Covalently attaching poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) to the nanoparticle surface creates a hydrophilic layer that reduces opsonization (the adsorption of blood proteins) and uptake by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), leading to prolonged circulation half-life [33] [34].

- Biomimetic Coating: Coating inorganic nanoparticles with biological membranes (e.g., red blood cell membranes, leukocyte membranes, or platelet membranes) confers the nanoparticles with the same biological functions as their parent cells. This includes superior biocompatibility, immune evasion, and prolonged circulation time [35].

Q2: Our encapsulated AMPs often show burst release instead of sustained release. How can we achieve better-controlled release kinetics?

A2: Burst release is often caused by weak surface adsorption or inadequate encapsulation. The following approaches can promote sustained release:

- Polymer Selection: Use biodegradable polymers with slower degradation kinetics, such as PLGA (poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) or PCL (poly(ε-caprolactone)). The release rate can be tuned by adjusting the polymer's molecular weight and lactide-to-glycolide ratio in PLGA [33] [36].

- Stimuli-Responsive Design: Incorporate materials that release their cargo in response to specific stimuli found in the target microenvironment, such as:

Q3: We are experiencing aggregation and instability with our inorganic nanoparticle formulations. What are the key factors for improving colloidal stability?

A3: Colloidal stability is achieved by providing sufficient electrostatic or steric repulsion between particles.

- Surface Charge (Zeta Potential): A high absolute value of zeta potential (typically > ±30 mV) indicates strong electrostatic repulsion that prevents aggregation. This can be controlled by using specific surfactants or stabilizers during synthesis, such as citrate or CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) [38].

- Surface Functionalization: Coating inorganic nanoparticles with a stable polymeric or silica shell provides a physical barrier and steric stabilization [35] [38]. For example, coating iron oxide nanoparticles with a silica layer prevents oxidation and aggregation [38].

Q4: How can we enhance the targeting efficiency of nanoparticles to specific bacterial infections?

A4: Active targeting can be achieved by conjugating targeting moieties to the nanoparticle surface.

- Ligand Conjugation: Attach antibodies, aptamers, or specific peptides that recognize and bind to antigens or receptors on the surface of the target bacterial cells [15]. This requires prior functionalization of the nanoparticle surface with reactive groups (e.g., carboxyl, amine, thiol) for bioconjugation [38].

- Biomimetic Approaches: Using membranes derived from specific cells, such as macrophages, can inherit their inherent ability to target infection sites [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Nanoparticle Synthesis and Formulation

| Problem | Possible Causes | Suggested Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low AMP Encapsulation Efficiency | - Hydrophilic AMP partitioning into aqueous phase during emulsion.- Rapid diffusion of AMP during solvent removal.- Poor interaction between AMP and nanoparticle matrix. | - Use a double emulsion (W/O/W) method for hydrophilic AMPs [33] [36].- Optimize the organic-to-aqueous phase ratio.- Incorporate charged polymers to promote ionic interaction with charged AMPs. |

| Large Polydispersity (Heterogeneous Size) | - Inadequate homogenization or sonication energy.- Uncontrolled nucleation and growth during synthesis.- Aggregation during purification or storage. | - Increase homogenization speed/sonication power and time [33].- Use microfluidic reactors for precise mixing control [39].- Optimize the type and concentration of stabilizers/surfactants. |

| Poor Colloidal Stability (Aggregation) | - Low surface charge (low zeta potential).- Inadequate steric stabilization.- Storage conditions (e.g., temperature, ionic strength). | - Purify nanoparticles to remove unbound stabilizers.- Introduce PEG or other steric stabilizers [33].- Store nanoparticles in deionized water at 4°C and avoid freeze-thaw cycles. |

| Unexpected Cytotoxicity | - Cytotoxicity of unreacted reagents or solvents.- Cationic surface charge causing membrane disruption.- Rapid release of high local doses of AMP. | - Improve purification (dialysis, tangential flow filtration) to remove residuals [33].- Modify surface charge to neutral or slightly negative.- Reformulate to achieve a more sustained release profile. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Functional Performance Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Suggested Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Short Circulation Time | - Rapid clearance by the immune system (MPS).- Large nanoparticle size (>200 nm).- Opsonization. | - PEGylate the nanoparticle surface [34].- Use a biomimetic red blood cell membrane coating [35].- Ensure nanoparticle size is optimally between 10-150 nm. |

| Insufficient Targeted Release | - Lack of specific targeting ligands.- Stimuli-responsive mechanism not activated in target microenvironment.- Ligand density too high or too low. | - Conjugate specific targeting moieties (e.g., antibodies, peptides) [15].- Characterize the target site's pH, enzyme, or redox conditions and tailor the responsive material accordingly [37].- Optimize ligand density during conjugation chemistry. |

| Loss of AMP Bioactivity | - Harsh synthesis conditions (organic solvents, sonication) denature AMP.- Undesirable interactions with the nanoparticle matrix. | - Use mild preparation methods like nanoprecipitation or ionic gelation where possible [36].- Consider pre-loading stabilizers (e.g., albumin) to protect the AMP. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparation of AMP-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles via Double Emulsion (W/O/W) Solvent Evaporation

This method is ideal for encapsulating hydrophilic antimicrobial peptides [33] [36].

1. Materials:

- Polymer: PLGA (e.g., 50:50 lactide:glycolide, MW 10-30 kDa).

- Solvent: Dichloromethane (DCM) or Ethyl Acetate.

- Aqueous Phases: Primary (W1): AMP dissolved in deionized water. Secondary (W2): Surfactant solution (e.g., 1-5% PVA, polyvinyl alcohol) in water.

- Equipment: Probe sonicator, magnetic stirrer, centrifugation.

2. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Primary Emulsion (W1/O): Dissolve 100 mg PLGA in 2 mL DCM. Add 0.5 mL of the aqueous AMP solution (W1). Probe sonicate this mixture on ice (e.g., 50-100 W for 30-60 sec) to form a stable water-in-oil (W1/O) emulsion.

- Secondary Emulsion (W1/O/W2): Immediately pour the primary emulsion into 20 mL of the external aqueous PVA solution (W2). Vigorously stir or sonicate again to form a double emulsion (W1/O/W2).

- Solvent Evaporation: Stir the double emulsion at room temperature for 4-6 hours to allow the organic solvent to evaporate and the nanoparticles to harden.

- Collection & Purification: Centrifuge the nanoparticle suspension (e.g., 20,000 rpm, 30 min) to pellet the nanoparticles. Wash the pellet 2-3 times with deionized water to remove PVA and unencapsulated AMP.

- Storage: Re-suspend the final nanoparticle pellet in a suitable buffer (e.g., PBS) and store at 4°C.

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of this synthesis method.

Protocol 2: Biomimetic Coating of Inorganic Nanoparticles with Cell Membranes

This protocol describes coating pre-synthesized inorganic nanoparticles (e.g., gold, silica) with a natural cell membrane to prolong circulation [35].

1. Materials:

- Source Cells: Red blood cells (RBCs) or macrophages.

- Inorganic Nanoparticles: Pre-synthesized and characterized nanoparticles (e.g., ~100 nm).

- Buffers: Hypotonic lysing buffer, PBS (phosphate-buffered saline).

- Equipment: Extruder with polycarbonate membranes, centrifugation.

2. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Membrane Derivation: Isolate the desired cells (e.g., from whole blood). Lyse the cells in a hypotonic buffer and centrifuge to separate the membrane fraction from intracellular contents. Wash the derived membranes repeatedly.

- Membrane Vesicle Formation: Sonicate the membrane fragments and extrude them through a porous membrane (e.g., 400 nm) to form cell-membrane-derived vesicles.

- Fusion/Coating: Co-incubate the cell membrane vesicles with the inorganic nanoparticles. Subject the mixture to repeated extrusion through a smaller pore membrane (e.g., 100-200 nm). The mechanical force induces fusion, resulting in the cell membrane forming a continuous lipid bilayer around the nanoparticle core.

- Purification: Use density gradient centrifugation to isolate the successfully coated nanoparticles from free membrane fragments and uncoated nanoparticles.

Visualization: Nanoparticle Engineering and Characterization Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for developing and evaluating advanced nanoparticle formulations for targeted AMP delivery, integrating key concepts from stability enhancement and targeted release.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nanoparticle Formulation and Functionalization

| Category & Item | Function/Benefit | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polymers | ||

| PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) | Biodegradable, biocompatible synthetic polymer; allows sustained release; degradation rate tunable by LA:GA ratio [33] [36]. | Acidic degradation products may affect some AMPs. |

| PCL (Poly(ε-caprolactone)) | Slower degrading polyester than PLGA; suitable for long-term delivery [33]. | Slower drug release profile. |

| Chitosan | Natural, mucoadhesive polymer; promotes penetration at mucosal surfaces; cationic for complexation with nucleic acids or negative charges [36]. | Requires dissolution in acidic conditions; solubility varies with degree of deacetylation. |

| Lipids & Surfactants | ||

| DSPE-PEG | Phospholipid-PEG conjugate; used for PEGylation to create stealth nanoparticles and prolong circulation [35] [34]. | PEG chain length (e.g., PEG-2000, PEG-5000) impacts stealth properties. |

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) | Cationic surfactant; commonly used as a stabilizing and shape-directing agent in gold nanorod synthesis [38]. | Requires careful removal due to cytotoxicity. |

| PVA (Polyvinyl Alcohol) | Stabilizer and emulsifying agent in solvent evaporation methods; prevents nanoparticle aggregation during formation [33]. | Residual PVA can affect surface properties and cellular interactions. |

| Functionalization Agents | ||

| EDC/NHS (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide / N-Hydroxysuccinimide) | Carboxyl-to-amine crosslinkers; standard chemistry for conjugating targeting ligands (peptides, antibodies) to nanoparticle surfaces [38] [15]. | Reaction must be performed in aqueous buffers at controlled pH. |

| Maleimide-PEG-NHS | Heterobifunctional crosslinker; allows coupling between amine-containing nanoparticles and thiol-containing ligands (e.g., cysteine-terminated peptides) [15]. | Thiol groups must be reduced and free for reaction. |

| Characterization Tools | ||

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Instrument for measuring nanoparticle hydrodynamic size, size distribution (PDI), and aggregation state in solution [33]. | Sensitive to dust and impurities in sample. |

| Zeta Potential Analyzer | Measures surface charge of nanoparticles; key indicator of colloidal stability and potential for protein adsorption [33] [38]. | Measurement is sensitive to pH and ionic strength of the medium. |

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are considered potent tools for combating resistant bacterial infections due to their broad-spectrum antibacterial effects and unique membrane-disrupting mechanisms [40] [10]. However, their clinical translation faces significant challenges, including limited stability, susceptibility to enzymatic degradation, cytotoxicity, and poor pharmacokinetic properties [40] [10] [2]. These limitations result in a narrow therapeutic window and reduced in vivo efficacy, despite promising in vitro activity [2].

Hydrogel-based delivery systems present a promising strategy to overcome these challenges by providing localized, sustained release of AMPs directly at infection sites [41] [42]. These highly hydrated polymer networks protect labile AMPs from degradation, reduce systemic toxicity, and maintain therapeutic concentrations within the therapeutic window for extended periods [41] [42]. This technical resource provides practical guidance for researchers developing hydrogel-AMP formulations, addressing common experimental challenges through troubleshooting guides and detailed methodologies.

Mechanisms of Hydrogel Protection and Sustained Release

Hydrogels protect AMPs and control their release through several interconnected mechanisms:

Molecular Stabilization

Anionic polysaccharides in hydrogel formulations (e.g., xanthan gum, hyaluronic acid, propylene glycol alginate) significantly decrease the degradation rate of AMPs like vancomycin and daptomycin by electrostatic interactions between the ionizable amine groups of the drugs and the anionic carboxylate groups of the polysaccharides [43]. This creates a microenvironment where water molecules have lower mobility and reduced thermodynamic activity, thereby slowing hydrolytic degradation [43].

Controlled Release Mechanisms

- Diffusion-Controlled Release: Drug molecules diffuse from regions of high concentration through the gel matrix, with release rates dependent on mesh size and porosity [44] [42].

- Swelling-Controlled Release: The drug is dispersed within glassy hydrogel polymers that swell upon contact with biofluids, releasing the drug during chain relaxation [44].

- Affinity-Based Release: Specific interactions (electrostatic, hydrophobic, covalent) between the AMP and polymer chains provide additional control over release kinetics [42].

Table 1: Hydrogel Mechanisms for Addressing AMP Limitations

| AMP Limitation | Hydrogel Protection Mechanism | Technical Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic degradation | Physical barrier against proteases | Increased half-life in biological environments |

| Rapid clearance | Sustained, controlled release | Maintained therapeutic concentration |

| Cytotoxicity | Localized delivery | Reduced systemic exposure |

| Chemical instability | Protective microenvironment | Enhanced shelf-life and in vivo stability |

Quantitative Stabilization Data: Polysaccharide Hydrogels

Recent research has quantified the stabilization effects of various anionic polysaccharides on AMP degradation:

Table 2: Stabilization of Antimicrobial Peptides by Polysaccharide Hydrogels

| Polysaccharide | Antimicrobial Peptide | Degradation Rate Constant (kobs, day⁻¹) | Half-Life (days) | Stabilization Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer (pH 7.4) | Vancomycin | 5.5 × 10⁻² | 13.9 | Baseline |

| Xanthan Gum | Vancomycin | 2.1 × 10⁻² | 33.0 | 2.6-fold improvement |

| Hyaluronic Acid | Vancomycin | 2.3 × 10⁻² | 30.1 | 2.3-fold improvement |

| PGA | Vancomycin | 2.2 × 10⁻² | 31.5 | 2.4-fold improvement |

| Dextran | Vancomycin | 4.4 × 10⁻² | 15.8 | Minimal effect |

| Alginic Acid | Vancomycin | 5.4 × 10⁻² | 12.8 | No effect |

| Buffer (pH 7.4) | Daptomycin | 5.6 × 10⁻² | 12.4 | Baseline |

| Xanthan Gum | Daptomycin | 2.1 × 10⁻² | 33.0 | 2.7-fold improvement |

| PGA | Daptomycin | 2.3 × 10⁻² | 30.1 | 2.4-fold improvement |

| Hyaluronic Acid | Daptomycin | 7.2 × 10⁻² | 9.6 | Destabilization |

Data adapted from research on anionic polysaccharides for stabilization and sustained release of antimicrobial peptides [43].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Hydrogel-AMP Formulation Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Alginate, Chitosan, Hyaluronic Acid, Collagen, Gelatin | Biocompatible hydrogel base materials | Provide innate bioactivity; may require chemical modification for optimal controlled release [41] |

| Synthetic Polymers | Poly(ethylene glycol), Poly(vinyl alcohol), Poly(acrylic acid) | Tunable hydrogel matrices with controlled properties | Offer precise control over mechanical properties and degradation rates [41] [42] |

| Crosslinkers | Glutaraldehyde, Genipin, Methacrylates, EDAC | Create 3D network structure | Crosslinking density directly controls mesh size and drug release kinetics [41] |

| Stabilizing Agents | Xanthan Gum, Propylene Glycol Alginate | Enhance AMP stability in formulation | Electrostatic interactions with AMPs reduce degradation rates [43] |

| Characterization Reagents | Triton X-100, PBS, Enzymes (e.g., lysozyme) | Assess release profiles and stability | Simulate physiological conditions for in vitro testing [41] |

Experimental Protocol: Hydrogel Formulation and Characterization

Hydrogel Preparation with AMP Encapsulation

Materials: Selected polymer (e.g., alginate, PEG), crosslinker, AMP solution, buffer (PBS, pH 7.4), mixing apparatus.

Method:

- Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve polymer in buffer at 2-10% (w/v) with continuous stirring until fully hydrated and clear [41].

- Drug Incorporation: Add AMP solution (1-10 mg/mL final concentration) to polymer solution under gentle mixing to avoid denaturation [44].

- Crosslinking:

- Curing: Maintain at room temperature for 1-24 hours based on crosslinking kinetics [41].

Troubleshooting Tip: If AMP activity decreases significantly after encapsulation, verify that crosslinking chemistry doesn't modify critical amino acid residues in the peptide sequence.

In Vitro Release Kinetics Assessment

Materials: Phosphate buffered saline (PBS), protease solutions (e.g., trypsin), Franz diffusion cells, UV-Vis spectrophotometer or HPLC.

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely cut hydrogel discs (e.g., 10mm diameter × 2mm thickness) [41].

- Release Study Setup: Immerse samples in release medium (PBS, pH 7.4, 37°C) with mild agitation (50-100 rpm) [41].

- Sampling Protocol: Withdraw aliquots (200-500 μL) at predetermined intervals (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72 hours) and replace with fresh medium [41].

- Drug Quantification:

- Data Analysis: Calculate cumulative release and fit to kinetic models (zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas) [41].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for hydrogel formulation and characterization

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges and Solutions

FAQ 1: How can I reduce burst release from my hydrogel system?

Problem: Initial rapid drug release (burst release) depletes a significant portion of the AMP before sustained release begins, potentially causing local toxicity and reducing long-term efficacy [45].

Solutions:

- Increase crosslinking density to reduce mesh size and slow diffusion (e.g., increase crosslinker concentration by 25-50%) [44] [42].

- Implement composite systems by pre-encapsulating AMPs in nanocarriers (e.g., liposomes) before incorporating into hydrogels [45].

- Utilize affinity-based interactions between AMP and polymer chains (e.g., heparin-binding peptides with sulfated polysaccharides) [42].

- Apply coating layers with lower porosity on the hydrogel surface to create a diffusion barrier [44].

FAQ 2: What approaches improve encapsulation efficiency for hydrophobic AMPs?

Problem: Conventional hydrogels primarily encapsulate hydrophilic compounds, leading to low loading capacity for hydrophobic AMPs [45].

Solutions:

- Use liposomal hydrogels where hydrophobic AMPs are loaded into lipid bilayers before hydrogel incorporation [45].

- Employ polymer-drug conjugates where hydrophobic AMPs are covalently attached to hydrogel polymers via cleavable linkers [44].

- Implement mixed micelle-hydrogel systems that solubilize hydrophobic AMPs in micelle cores within the hydrogel matrix [45].

- Modify hydrogel polymers with hydrophobic domains that interact with hydrophobic AMPs through affinity interactions [42].

FAQ 3: How can I enhance the stability of AMPs in hydrogel formulations?

Problem: AMPs may degrade during storage or after administration, reducing therapeutic efficacy [43] [2].

Solutions:

- Select appropriate polysaccharide stabilizers based on quantitative stabilization data (see Table 2) [43].

- Modify peptide structure by incorporating D-amino acids or cyclization to reduce protease susceptibility before encapsulation [2].

- Optimize storage conditions including pH control, antioxidants, and temperature based on the specific AMP's degradation pathways [41].

- Use desiccated hydrogels that are rehydrated immediately before application to minimize hydrolysis during storage [41].

FAQ 4: How do I control release duration for different infection timelines?