Optimizing Antibacterial Production with Response Surface Methodology: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide on applying Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to optimize the production of antibacterials, such as bacteriocins and novel metabolites, from microbial sources.

Optimizing Antibacterial Production with Response Surface Methodology: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide on applying Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to optimize the production of antibacterials, such as bacteriocins and novel metabolites, from microbial sources. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of RSM, detailed methodological steps for experimental design and model fitting, advanced strategies for troubleshooting and enhancing model performance, and rigorous techniques for validation and comparative analysis. By synthesizing recent case studies and proven strategies, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to significantly increase antibacterial titers, streamline development processes, and enhance the reproducibility of their research for applications ranging from novel drug discovery to industrial-scale bioprocessing.

Understanding Response Surface Methodology and Its Role in Antibacterial Development

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is a collection of statistical and mathematical techniques used for developing, improving, and optimizing processes and products [1] [2]. The methodology focuses on modeling and analyzing problems where multiple independent variables influence one or more dependent responses, with the primary goal of finding the optimal conditions for these responses [3] [4].

First proposed by Box and Wilson in the 1950s, RSM has evolved into a fundamental tool for empirical model building and process optimization across numerous scientific and industrial fields [1] [4]. In the context of antibacterial production optimization research, RSM provides a systematic approach to understanding complex variable interactions while minimizing experimental effort, thereby accelerating development timelines and improving production efficiency [5] [6].

Key Terminology and Fundamental Concepts

Core Definitions

Understanding RSM requires familiarity with its specific terminology:

- Response Variable: The measurable output or quality characteristic of interest that is influenced by the input variables. In antibacterial production, this could include yield, purity, or potency [2].

- Independent Variables: The process parameters or factors that can be controlled and varied during experimentation. Also called factors or input variables [3].

- Experimental Region: The multidimensional space defined by the ranges of the independent variables being studied [2].

- Response Surface: The geometrical representation of the relationship between the independent variables and the response, typically visualized as 3D surfaces or 2D contour plots [7] [2].

- Optimization: The process of finding the values of independent variables that produce the most desirable response value, whether maximum, minimum, or target [1] [2].

Mathematical Foundation

RSM typically employs empirical models, most commonly second-order polynomial equations, to approximate the relationship between variables and responses. The general form of this model for k variables is [5]:

y = β₀ + ∑βᵢxᵢ + ∑βᵢᵢxᵢ² + ∑βᵢⱼxᵢxⱼ + ε

Where:

- y = predicted response

- β₀ = constant term

- βᵢ = linear coefficient

- βᵢᵢ = quadratic coefficient

- βᵢⱼ = interaction coefficient

- xᵢ, xⱼ = independent variables

- ε = random error term

This quadratic model can capture curvature in the response surface, enabling the location of optimal points [7] [4].

Table 1: Key Components of RSM Mathematical Models

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Constant term | β₀ | Expected response at center point |

| Linear effects | βᵢxᵢ | Main effect of each variable |

| Quadratic effects | βᵢᵢxᵢ² | Curvature in response |

| Interaction effects | βᵢⱼxᵢxⱼ | Synergistic/antagonistic effects between variables |

Objectives of Response Surface Methodology

RSM serves several critical objectives in process optimization, particularly in antibacterial production research:

Primary Optimization Objective

The fundamental objective is to identify optimal operational conditions that maximize or minimize one or more response variables. For instance, researchers may seek to maximize antibiotic yield while minimizing impurity formation [2]. This involves navigating the response surface to find regions that satisfy all operational constraints while achieving the desired response goals.

Understanding Variable Interactions

RSM enables researchers to quantify relationships and interactions between multiple variables and their collective impact on responses [7] [4]. This is particularly valuable in antibacterial production, where factors like temperature, pH, nutrient concentrations, and incubation time often interact in complex ways that cannot be revealed through traditional one-variable-at-a-time experimentation [5] [6].

Process Robustness Improvement

An important advanced application of RSM is robust parameter design, which aims to make processes insensitive to uncontrollable sources of variation (noise factors) [1]. This ensures consistent antibacterial production even when minor fluctuations occur in raw materials or environmental conditions.

Experimental Efficiency

RSM provides a systematic framework for efficient experimentation by reducing the number of experimental runs required to characterize complex systems [5] [8]. This efficiency accelerates research timelines and reduces costs, which is particularly valuable in resource-intensive fields like drug development.

Experimental Design Strategies in RSM

Core Design Types

RSM employs specialized experimental designs that efficiently explore the experimental region:

- Central Composite Design (CCD): The most popular RSM design, consisting of factorial points, center points, and axial (star) points that extend beyond the factorial range. CCD can be circumscribed, inscribed, or face-centered depending on the experimental constraints [1] [4].

- Box-Behnken Design (BBD): A spherical design with all points lying on a radius of √2 from the center, requiring fewer runs than CCD for the same number of factors. BBD avoids extreme conditions by not including corner points [4].

- Three-Level Factorial Designs: Full factorial designs with each factor at three levels (low, medium, high), though these become resource-intensive with more than 3-4 factors [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Common RSM Experimental Designs

| Design Type | Number of Runs (3 factors) | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Composite | 15-20 | Estimates all model parameters; rotatable | May require extreme factor levels |

| Box-Behnken | 13-15 | Avoids extreme conditions; efficient | Cannot include categorical factors |

| Three-Level Factorial | 27 | Comprehensive; direct interpretation | Rapidly becomes large with more factors |

Design Selection Considerations

Choosing an appropriate experimental design depends on several factors:

- Number of factors to be investigated

- Shape of the experimental region (spherical, cubic, irregular)

- Resource constraints (time, materials, budget)

- Objective of the study (screening, optimization, robustness testing)

- Need to avoid extreme factor combinations for safety or practical reasons

For most antibacterial optimization studies with 3-5 factors, Central Composite Designs or Box-Behnken Designs provide the best balance of efficiency and information quality [1] [2].

Implementation Protocol for Antibacterial Production Optimization

Preliminary Screening Phase

Before implementing full RSM optimization, researchers must identify the critical factors influencing antibacterial production:

- Define the problem and primary response variables (e.g., antibiotic yield, potency)

- Identify potential influencing factors through literature review and preliminary knowledge

- Conduct screening experiments using fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman designs to identify the 3-5 most significant factors

- Determine appropriate ranges for each significant factor based on screening results

RSM Experimental Protocol

The core RSM implementation follows this systematic approach:

Model Development and Validation Protocol

After conducting experiments according to the design matrix:

- Fit the response surface model using multiple regression analysis

- Perform statistical validation through Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

- Check model adequacy using R² values, lack-of-fit tests, and residual analysis

- Visualize the response surface with 3D surface plots and 2D contour plots

- Identify optimal conditions using numerical optimization or graphical analysis

- Confirm predicted optimum with additional validation experiments

Application in Antibacterial Research: Case Examples

Optimization of Phage-Antibiotic Combinations

A recent study demonstrated RSM's power in optimizing bacteriophage-antibiotic combinations against Acinetobacter baumannii biofilms [5]. Researchers employed RSM to model the interactive effects of seven antibiotics combined with bacteriophage vBAbaPAGC01, identifying optimal concentration combinations that reduced biofilm biomass by up to 88.74%. The study revealed mostly synergistic interactions, with the phage-imipenem combination showing highest efficacy.

Microbial Pigment Production with Antimicrobial Activity

RSM was successfully applied to optimize pigment production by Fusarium foetens CBS 110286, with the optimized pigment demonstrating significant antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli [6]. Five independent variables (temperature, incubation time, peptone, fructose, and initial pH) were simultaneously optimized using Design-Expert software, showcasing RSM's utility in maximizing secondary metabolite production with antimicrobial properties.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of RSM in antibacterial research requires specific reagents and tools:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Antibacterial RSM Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in RSM Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media Components | Peptone, Fructose [6] | Nutrient factors optimized for metabolite production |

| Antibacterial Agents | Gentamicin, Meropenem, Amikacin [5] | Test compounds for combination therapy optimization |

| Solvents & Extraction Agents | Sodium hydroxide, Hydrochloric acid [8] | Process parameters in extraction optimization |

| Buffer Systems | Phosphate buffers, pH modifiers | Control and optimize physicochemical parameters |

| Analysis Reagents | Crystal violet [5] | Biomass staining for response measurement |

| Statistical Software | Design-Expert, Minitab, MATLAB [9] [6] | Experimental design and response surface modeling |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Modern RSM applications continue to evolve with several advanced implementations:

- Dual Response Surface Methodology: Simultaneously optimizes multiple responses, such as maximizing yield while minimizing impurities [1]

- Mixture Experiments: Specialized designs for optimizing component proportions in formulations [1]

- Robust Parameter Design: Makes processes insensitive to uncontrollable noise factors [1]

- Computer Experiments and Surrogate Modeling: Uses computational models when physical experimentation is costly [1]

In antibacterial research, these advanced approaches enable more comprehensive optimization of production processes, formulation development, and therapeutic efficacy studies.

Response Surface Methodology provides a powerful statistical framework for optimizing antibacterial production processes through systematic experimentation, mathematical modeling, and multi-factor analysis. By enabling researchers to efficiently navigate complex variable spaces and identify optimal operational conditions, RSM significantly accelerates development timelines while improving process efficiency and robustness. The methodology's ability to quantify interactive effects between multiple factors makes it particularly valuable in the complex biological systems inherent to antibacterial production, positioning RSM as an indispensable tool in modern pharmaceutical research and development.

The Critical Advantages of RSM Over One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) Experiments

In antibacterial production research, optimizing complex fermentation processes and combination therapies is crucial for enhancing yield, efficacy, and cost-efficiency. Traditionally, many researchers have employed the One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) approach, where each process variable is investigated independently while keeping others constant [10]. While conceptually simple, this method presents significant limitations in capturing the complex interactions prevalent in biological systems. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) has emerged as a statistically superior framework that addresses these shortcomings through multivariate experimental design and analysis [11]. This Application Note delineates the critical advantages of RSM over OFAT, providing researchers with structured protocols and visual guides for implementing this powerful methodology in antibacterial optimization research.

Theoretical Foundation: OFAT vs. RSM

Fundamental Limitations of the OFAT Approach

The OFAT method systematically varies a single factor across a range of values while maintaining all other factors at fixed levels [10]. Despite its historical prevalence and intuitive appeal, this approach suffers from three critical deficiencies in complex antibacterial research:

- Inability to Detect Interactions: OFAT assumes factor independence, ignoring potential synergistic or antagonistic effects between process variables [10]. In antibiotic combination therapies, this can lead to missed opportunities for enhanced efficacy or failure to identify antagonistic pairs.

- Inefficient Resource Utilization: OFAT requires a large number of experimental runs, making it time-consuming, costly, and impractical when dealing with multiple factors [12] [10].

- Suboptimal Solutions: Without capturing factor interactions, OFAT often identifies local optima rather than the true global optimum for the process [10].

The RSM Framework: A Multivariate Approach

RSM is a collection of statistical and mathematical techniques that model and analyze problems where multiple independent variables influence a dependent response, with the goal of optimizing this response [13]. The methodology employs carefully designed experiments to build empirical models, typically using first or second-order polynomials, to describe the relationship between factors and responses [5]. The core advantages of RSM stem from its ability to efficiently explore the entire factor space, quantify interactions, and identify optimal conditions with minimal experimental runs.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between OFAT and RSM Approaches

| Characteristic | OFAT | RSM |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Strategy | Varies one factor while holding others constant | Systematically varies multiple factors simultaneously |

| Factor Interactions | Cannot detect or quantify interactions | Explicitly models and quantifies interaction effects |

| Experimental Efficiency | Low; requires many runs for multiple factors | High; optimized design minimizes required runs |

| Mathematical Foundation | No comprehensive model | Builds empirical polynomial model of the process |

| Optimization Capability | Limited to identified factor levels | Can predict optimum conditions within design space |

| Resource Consumption | High (time, materials, cost) | Significantly reduced |

Critical Comparative Advantages of RSM

Detection of Interaction Effects

The most significant advantage of RSM is its ability to identify and quantify interaction effects between factors, which OFAT fundamentally cannot detect [10]. In antibacterial research, this is particularly crucial when optimizing combination therapies or complex media formulations.

Experimental Evidence: A study optimizing phage-antibiotic combinations against Acinetobacter baumannii biofilms demonstrated that RSM could effectively model the synergistic interactions between bacteriophages and specific antibiotics (imipenem, amikacin), while also identifying antagonistic relationships (with gentamicin) [5]. This level of insight would be impossible with OFAT, potentially leading to ineffective therapeutic combinations.

Enhanced Experimental Efficiency

RSM employs statistically designed experiments that extract maximum information from minimal experimental runs, dramatically improving resource efficiency.

Quantitative Comparison: In a direct comparison for optimizing endoglucanase production, RSM achieved higher enzyme production (3.96 U/mL) compared to OFAT (3.55 U/mL) while requiring fewer experimental runs to characterize the multi-factor space [14]. This 11.5% improvement in yield coupled with reduced experimental burden exemplifies the dual efficiency advantage of RSM.

Comprehensive Process Optimization

While OFAT can identify individual factor effects, RSM generates a predictive mathematical model that enables true process optimization across the entire design space.

Case Study: For auxin (IAA) production by Pantoea agglomerans, RSM optimization led to a 40% increase in production (208.3 ± 0.4 mg IAAequ/L) compared to previous OFAT-derived conditions [15]. The RSM model identified optimal aeration conditions (rotation speed: 180 rpm; medium liquid-to-flask volume ratio: 1:10) that would be extremely difficult to discover through sequential OFAT experimentation.

Table 2: Documented Efficiency Gains of RSM Over OFAT in Bioprocess Optimization

| Research Context | Organism/System | Response Optimized | Improvement with RSM | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibacterial Production | Streptomyces alfalfae XN-04 | Biomass | 7.47-fold increase | [12] |

| Auxin Production | Pantoea agglomerans C1 | Indole-3-acetic acid | 40% increase | [15] |

| Bacteriocin Production | Lactococcus lactis Gh1 | BLIS production | 1.40-fold higher | [16] |

| Antibacterial Production | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | Bacteriocins/organic acids | >10-fold increase | [17] |

| Enzyme Production | Aspergillus oryzae | Endoglucanase (CMCase) | 11.5% increase | [14] |

Experimental Design and Protocol

Selection of RSM Design

The two most prevalent RSM designs for antibacterial optimization are Central Composite Design (CCD) and Box-Behnken Design (BBD), each with distinct advantages:

Central Composite Design (CCD)

- Requires 5 levels for each factor (-α, -1, 0, +1, +α)

- Excellent for sequential experimentation

- Provides high-quality prediction across the design space

- Ideal for 2-5 factor systems [11]

Box-Behnken Design (BBD)

- Requires only 3 levels for each factor (-1, 0, +1)

- More efficient than CCD for the same number of factors

- Avoids extreme factor combinations

- Suitable for 3-7 factor systems [11]

Protocol: RSM Optimization of Antibacterial Production

Step 1: Define Objective and Critical Process Parameters

- Clearly identify the primary response (e.g., antibiotic yield, biofilm inhibition, MIC reduction)

- Select independent variables based on prior knowledge or screening designs

- Define practical ranges for each variable

Step 2: Experimental Design and Layout

- Select appropriate RSM design (CCD or BBD) based on factors and resource constraints

- Randomize run order to minimize bias

- Include center points to estimate pure error

Step 3: Model Development and Validation

- Conduct experiments according to the design matrix

- Fit experimental data to second-order polynomial model:

y = β₀ + Σβᵢxᵢ + Σβᵢᵢxᵢ² + Σβᵢⱼxᵢxⱼ + ε [5]

- Evaluate model adequacy using ANOVA (R², adjusted R², predicted R²)

- Ensure model lack-of-fit is not significant

Step 4: Response Surface Analysis and Optimization

- Visualize factor-response relationships using 3D surface and 2D contour plots

- Identify optimal factor levels using desirability function approach

- Verify predictions with confirmatory experiments

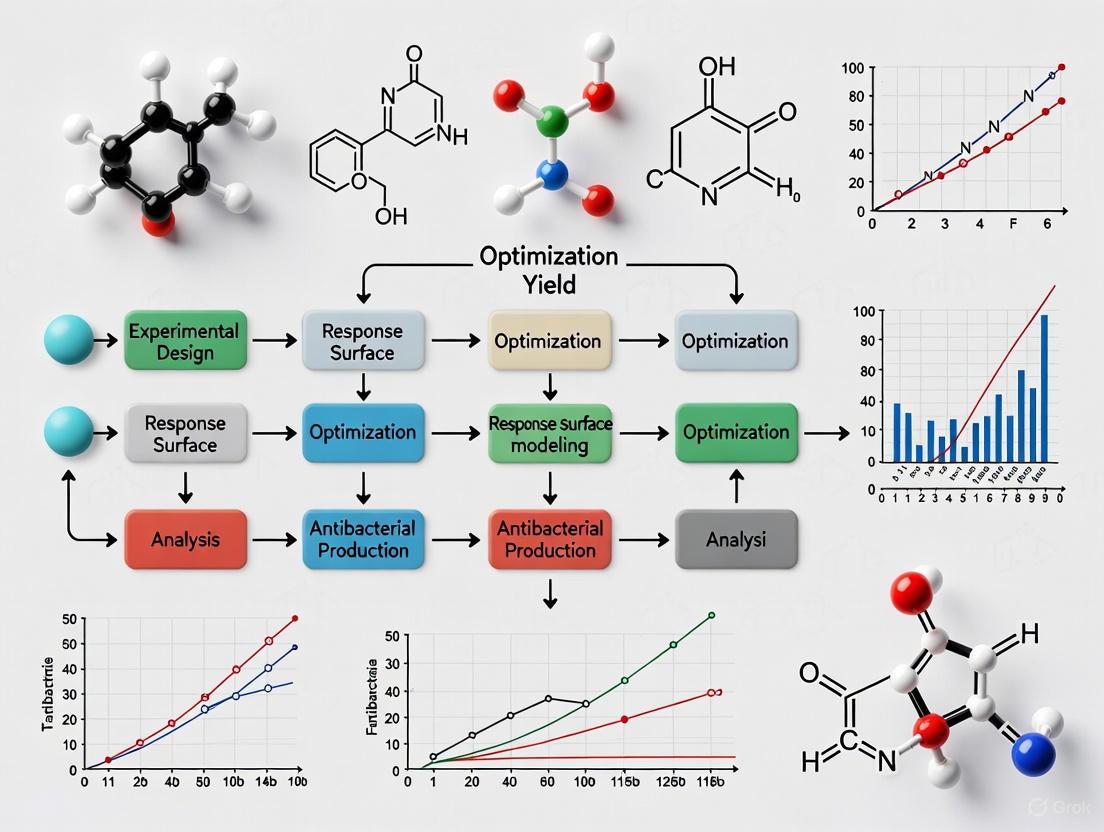

The following workflow diagram illustrates the strategic RSM optimization process:

Application Case Study: Phage-Antibiotic Synergy Optimization

Background and Objective

A recent study exemplifies RSM's superiority in optimizing combination therapies against biofilm-forming Acinetobacter baumannii [5]. The research objective was to maximize biofilm reduction through optimal combinations of bacteriophage vBAbaPAGC01 and seven different antibiotics.

RSM Implementation

Experimental Design: A Central Composite Design was employed with two normalized factors:

- Antibiotic concentration (cA): 0-1024 µg/mL → normalized to 0-1

- Phage concentration (cP): 10³-10⁸ PFU/mL → normalized to 0-1 [5]

Mathematical Modeling: The quadratic model describing the relationship was expressed as:

Biofilm Reduction = β₀ + β₁cA + β₂cP + β₁₁cA² + β₂₂cP² + β₁₂cA·cP + ε

Key Findings: RSM analysis revealed profound differences in interaction patterns:

- Synergistic: Phage-imipenem combinations achieved 88.74% biofilm reduction

- Antagonistic: Phage-gentamicin combinations showed reduced efficacy

- Resource-Efficient: Phage-amikacin combination at minimal concentrations (cA=0.00195, cP=0.38) provided substantial efficacy [5]

Protocol: Biofilm Challenge Assay

Materials:

- 48-hour A. baumannii biofilm grown in 96-well plates with medium replacement every 12 hours

- Antibiotic stock solutions at appropriate concentrations

- Bacteriophage suspension titered by double-layer agar method

- Crystal violet staining solution (1%)

- Methanol and acetic acid (33%) for destaining

Method:

- Rinse established biofilms five times with PBS buffer

- Add TSB medium containing predetermined phage-antibiotic combinations according to CCD matrix

- Incubate plates for 8 hours at 37°C

- Remove culture, rinse with PBS, and fix biofilm with methanol for 10 minutes

- Stain with crystal violet solution (1%) for 10 minutes

- Wash excess stain and resolubilize with acetic acid:methanol (2:8)

- Measure absorbance at 595 nm to quantify remaining biofilm biomass

- Calculate percentage reduction compared to untreated controls

Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Antibacterial RSM Studies

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Research Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Composite Design | 5-level factorial with center points | Maps linear, quadratic & interaction effects | Antibiotic-phage synergy optimization [5] |

| Box-Behnken Design | 3-level spherical design | Efficiently models curvature with fewer runs | Bacteriocin production optimization [17] |

| Statistical Software | Design-Expert, MINITAB, R | Generates design matrices & analyzes responses | All RSM applications [13] |

| Plackett-Burman Design | Two-level screening design | Identifies significant factors from many variables | Preliminary screening of medium components [12] |

| Crystal Violet Assay | 1% solution in aqueous buffer | Quantifies biofilm biomass | Assessment of antibiofilm efficacy [5] |

The transition from OFAT to RSM represents a methodological evolution essential for modern antibacterial optimization research. The documented advantages—interaction detection, experimental efficiency, and comprehensive optimization—provide compelling evidence for RSM adoption across various applications, from antibiotic production to combination therapy development.

For researchers implementing RSM, we recommend:

- Begin with factor screening designs when dealing with numerous potential variables

- Select CCD for sequential optimization or when precise prediction across the space is critical

- Choose BBD for resource-constrained scenarios or when extreme factor combinations are impractical

- Always include confirmation experiments to validate model predictions

- Utilize available statistical software to facilitate design generation and analysis

The robust mathematical foundation of RSM, combined with its proven efficacy in diverse antibacterial applications, establishes it as an indispensable tool for researchers seeking to optimize complex biological systems efficiently and effectively.

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is a collection of statistical and mathematical techniques fundamental for developing, improving, and optimizing processes, particularly in the realm of antibacterial production optimization [1]. Its primary application is for modeling and analyzing problems in which a response of interest is influenced by several variables, with the overarching goal of determining the optimal conditions for that response [1]. In the context of antibacterial research, this response could be the yield of an antimicrobial peptide, the potency of a bacteriocin, or the biomass of a productive microbial strain [18] [17] [19]. The Quadratic Model is the cornerstone of RSM, as it empirically captures not only the linear effects of factors but also their curvature and interaction effects, which are crucial for identifying a true optimum [1] [4].

The model's ability to map the relationship between multiple independent variables (e.g., temperature, pH, nutrient concentrations) and a dependent response (e.g., antibacterial yield) makes it indispensable for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to enhance the production of novel antimicrobial agents in the face of rising multidrug-resistant pathogens [5] [20]. By applying this model, scientists can efficiently navigate the experimental space to find the factor levels that maximize or minimize the response, thereby accelerating the development of much-needed therapeutic compounds [17] [20].

Deconstruction of the Quadratic Model Equation

The standard second-order polynomial model, which is the most common form of a quadratic model in RSM, is expressed by the following equation [5]:

y = β₀ + ∑ᵢ βᵢ xᵢ + ∑ᵢ βᵢᵢ xᵢ² + ∑ᵢ ∑ⱼ βᵢⱼ xᵢ xⱼ + ε [5]

Table 1: Components of the Quadratic Model Equation

| Symbol | Term | Statistical Interpretation | Practical Significance in Antibacterial Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| y | Response | The predicted output variable. | The measured outcome, e.g., zone of inhibition (mm), biomass yield (g/L), or metabolite titer [5] [17]. |

| β₀ | Constant | The model intercept; the mean value of the response at the center point. | The baseline activity or production level under average conditions [4]. |

| xᵢ, xⱼ | Independent Variables | The coded or actual levels of the input factors. | Process parameters such as temperature (°C), pH, agitation rate (rpm), or nutrient concentration (g/L) [18] [17]. |

| βᵢ | Linear Coefficient | The main effect of factor i; it represents the slope of the plane. |

The individual and direct impact of changing a single factor on the antibacterial production [1]. |

| βᵢᵢ | Quadratic Coefficient | The second-order effect of factor i; it indicates the curvature of the response surface. |

Captures nonlinear behavior, such as diminishing returns or a distinct optimum pH for growth [1] [17]. |

| βᵢⱼ | Interaction Coefficient | The interaction effect between factors i and j; it signifies how the effect of one factor changes with the level of another. |

Reveals synergies or antagonisms, e.g., how the optimal temperature might shift with pH [18] [1]. |

| ε | Error | The residual term accounting for experimental variability not explained by the model. | Represents the noise or random error inherent in the biological system [5]. |

The power of this model lies in its components. The linear coefficients (βᵢ) describe the primary direction of the response, while the quadratic coefficients (βᵢᵢ) are essential for identifying a maximum or minimum point within the experimental region, as they capture the rate of change of the main effects [1]. Furthermore, the interaction coefficients (βᵢⱼ) are critical for process optimization, as a significant interaction indicates that the effect of one factor is dependent on the level of another factor [18]. For instance, research on Lactiplantibacillus plantarum demonstrated that initial pH was the most significant linear factor, but its interaction with temperature and incubation time was key to achieving a more than 10-fold increase in antibacterial titer [17].

Experimental Protocol for Model Application

Protocol: Implementing a Quadratic Model for Optimizing Antibacterial Production

This protocol outlines the steps to apply the quadratic model using a Box-Behnken Design (BBD) to optimize culture conditions for antibacterial production, based on methodologies successfully used for Streptomyces and Lactobacillus species [18] [17].

1. Problem Definition and Response Selection

- Objective: Clearly define the goal, e.g., "To maximize the production of antimicrobial peptides by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum" [17].

- Response Variable (y): Select a quantifiable and relevant metric. In this case, the antibacterial titer or the diameter of the inhibition zone against a target pathogen like Staphylococcus aureus would be appropriate [17] [19]. Ensure a robust and reproducible bioassay method is in place, such as the well-diffusion assay [19].

2. Factor Screening and Level Selection

- Independent Variables (xᵢ): Based on prior knowledge or screening designs (e.g., Plackett-Burman), select the most influential factors. For a BBD with three factors, relevant choices are:

- Levels: Define low (-1), middle (0), and high (+1) levels for each factor. For example:

3. Experimental Design and Execution

- Design Matrix: Use statistical software to generate a BBD matrix. For 3 factors, this will result in 12 experimental runs plus center points (e.g., 5), totaling 17 runs [18] [4].

- Randomization: Execute all experimental runs in a randomized order to minimize the effect of confounding variables.

- Data Collection: For each run, prepare the culture medium, inoculate with the bacterium, incubate under the specified conditions, and measure the response (antibacterial titer or inhibition zone) using the standardized bioassay [18] [19].

4. Model Fitting and Analysis

- Regression Analysis: Input the experimental data into statistical software to perform multiple regression analysis. The software will fit the data to the quadratic model and estimate the coefficients (β₀, βᵢ, βᵢᵢ, βᵢⱼ) [1] [4].

- Model Validation: Assess the model's adequacy using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Key metrics to check include:

- p-value: The model and significant terms should have p-values < 0.05 [1].

- R² and Adjusted R²: Indicate the proportion of variance in the response explained by the model. Values above 0.90 are generally desirable [1].

- Lack-of-Fit Test: A non-significant lack-of-fit (p > 0.05) is good, suggesting the model fits the data well [1].

5. Optimization and Validation

- Optimum Identification: Use the software's optimization function to identify the factor levels that maximize the predicted response. The fitted model will be of the form:

y = β₀ + β₁A + β₂B + β₃C + β₁₁A² + β₂₂B² + β₃₃C² + β₁₂AB + β₁₃AC + β₂₃BC[18] [4]. - Confirmation Experiment: Perform a new experiment at the predicted optimal conditions to validate the model. Compare the observed response with the model's prediction to verify its accuracy [18] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for RSM in Antibacterial Production

| Item | Function/Application | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Box-Behnken Design (BBD) | An efficient, spherical, response surface design requiring fewer runs than a Central Composite Design (CCD) for 3 or more factors. It is ideal for fitting quadratic models [18] [4]. | Used to optimize temperature, pH, and agitation for Streptomyces sp. MFB27, revealing different optima for growth vs. metabolite production [18]. |

| Central Composite Design (CCD) | A popular RSM design that augments a factorial or fractional factorial design with axial and center points, allowing for estimation of curvature [1] [4]. | Applied to optimize a plant-based fermentation medium (brown rice, yeast extract, lactose) for antimicrobial CFS production by L. plantarum [21]. |

| Statistical Software | Software platforms (e.g., Design-Expert, R, Minitab) are essential for generating design matrices, performing regression analysis, conducting ANOVA, and visualizing response surfaces [6]. | Used to analyze the effects of five variables (temp, time, peptone, fructose, pH) on pigment/antimicrobial production in Fusarium foetens [6]. |

| Crystal Violet Assay | A standard bioassay for quantifying biofilm biomass, used to measure the response in experiments optimizing antibiofilm agents [5]. | Employed to measure the reduction in Acinetobacter baumannii biofilm biomass by optimized phage-antibiotic combinations [5]. |

| Well/Cup Diffusion Assay | A primary method for quantifying antimicrobial activity by measuring the zone of inhibition (ZOI) around a sample-containing well in a seeded agar plate [19]. | Used to screen for and confirm the antimicrobial activity of Bacillus licheniformis SN2 supernatants against Staphylococcus aureus [19]. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

The following table compiles quantitative data from various studies that successfully applied the quadratic model to optimize antibacterial production, demonstrating the model's versatility and power.

Table 3: Quantitative Results from RSM Optimization in Antibacterial Production

| Organism / System | Response Variable(s) | Key Optimized Factors | Optimal Conditions | Optimization Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces sp. MFB27 | Biomass growth & secondary metabolite production | Temperature, pH, Agitation rate | Growth: 33°C, pH 7.3, 110 rpmMetabolites: 31-32°C, pH 7.5-7.6, 112-120 rpm | Significant enhancement of biomass and metabolite yield under distinct optimal conditions [18]. | [18] |

| Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | Production of antibacterials (Bacteriocins) | Temperature, Initial pH, Incubation time | 35°C, pH 6.5, 48 h | More than a 10-fold increase in the titer of produced antibacterials [17]. | [17] |

| Phage-Imipenem Combination | Reduction of A. baumannii biofilm biomass | Antibiotic concentration, Phage concentration | Specific optimized combination points | Synergistic effect achieving up to 88.74% reduction in biofilm biomass [5]. | [5] |

| Bacillus licheniformis SN2 | Suppression of S. aureus growth (Antimicrobial peptide production) | Yeast extract, Peptone, NaCl concentrations | Yeast extract: 7.4 g/LPeptone: 2 g/LNaCl: 2.8 g/L | Increased suppression of S. aureus growth by 1.3-fold and accelerated the process by 6 hours [19]. | [19] |

| L. plantarum K014 (in Brown Rice Media) | Inhibition zone against Cutibacterium acnes | Brown rice, Yeast extract, Lactose concentrations | 35 g/L Brown Rice, 15 g/L Yeast Extract, 30 g/L Lactose | Production of a stable, plant-based anti-acne agent with a defined inhibition zone [21]. | [21] |

Within the field of industrial microbiology and antibacterial drug development, optimizing the production of bioactive compounds is paramount to enhancing yield, efficacy, and economic viability. This article details application notes and protocols for the optimized production of antibacterial agents from three key bacterial systems: Streptomyces for antifungal metabolites, Lactobacillus for bacteriocins, and recombinant E. coli for the biocatalytic enzyme cyclohexanone monooxygenase (CHMO). The content is framed within a broader research thesis on the application of Response Surface Methodology (RSM), a powerful statistical and mathematical technique used for modeling and optimizing complex bioprocesses. The methodologies presented herein are designed for researchers, scientists, and professionals engaged in drug development and industrial fermentation, providing detailed, actionable protocols to accelerate and refine their experimental workflows.

Application Note & Protocol 1: Streptomyces sp. for Antifungal Metabolites

Background and Objective

Streptomyces species are renowned for their prolific production of bioactive secondary metabolites. The objective of this protocol is to maximize the production of antifungal metabolites from Streptomyces sp. strain KN37 against crop pathogenic fungi like Rhizoctonia solani, leveraging RSM for process optimization [22].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Fermentation Media Optimization

Initial Screening (One-Factor-at-a-Time): Begin by identifying suitable carbon and nitrogen sources.

- Carbon Sources: Test millet, corn starch, cellulose, sucrose, maltose, glycerin, and dextrin. Millet was identified as the optimal carbon source, increasing antifungal activity by 25% compared to the original medium [22].

- Nitrogen Sources: Test yeast extract, soybean meal, peanut powder, tryptone, carbamide, NH₄Cl, and NH₄CO₃. Yeast extract was selected as the optimal nitrogen source [22].

- Mineral Salts: Evaluate K₂HPO₄, MgSO₄, FeSO₄, and NaCl. The addition of K₂HPO₄ was found to notably improve antifungal activity [22].

Statistical Optimization (RSM):

- Plackett-Burman Design (PBD): Use this design to screen for significant factors influencing bioactivity. For strain KN37, millet, yeast extract, and K₂HPO₄ were identified as the key medium components [22].

- Central Composite Design (CCD): Further optimize the concentrations of the significant factors (millet, yeast extract, K₂HPO₄) identified by the PBD to determine their optimal levels [22].

Culture Condition Optimization

Determine the optimal physical conditions for fermentation through single-factor experiments:

- Inoculum: Use 4% (v/v) of a seed culture grown in a suitable medium [22].

- Temperature: Incubate at 25°C [22].

- Initial pH: Set to pH 8.0 [22].

- Agitation: Maintain at 150 rpm [22].

- Fermentation Time: 9 days [22].

- Liquid Volume: 100 mL in an appropriate flask [22].

Antifungal Activity Assay

- Employ the mycelial growth rate method to quantify the inhibition of Rhizoctonia solani [22].

- Calculate the inhibition rate using the formula:

Inhibition Rate (%) = [(Diameter of control - Diameter of treatment) / Diameter of control] × 100[22].

Key Data and Optimization Results

Table 1: Optimized Fermentation Parameters for Streptomyces sp. KN37

| Parameter | Original Value | Optimized Value | Impact on Antifungal Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Source | Not Specified | Millet (20 g/L) | Increased inhibition rate by 25% |

| Nitrogen Source | Not Specified | Yeast Extract (1 g/L) | Significant positive effect |

| Mineral Salt | Not Specified | K₂HPO₄ (0.5 g/L) | Significant positive effect |

| Temperature | Not Specified | 25 °C | Maximal activity achieved |

| Initial pH | Not Specified | 8.0 | Maximal activity achieved |

| Agitation Speed | Not Specified | 150 rpm | Maximal activity achieved |

| Fermentation Time | Not Specified | 9 days | Inhibition rate reached 44.93% |

| Antifungal Rate | 27.33% | 59.53% | Aligned with RSM prediction (53.03%) |

Workflow Diagram: Streptomyces Metabolite Optimization

Application Note & Protocol 2: Lactobacillus for Bacteriocin Production

Background and Objective

Lactobacillus species produce bacteriocins, which are antimicrobial peptides with utility as food preservatives and therapeutic agents. This protocol aims to optimize the production of bacteriocins from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus rhamnosus using RSM [17] [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Strain and Inoculum Preparation

- Strains: Lactiplantibacillus plantarum or Lactobacillus rhamnosus CW40 [17] [23].

- Culture Medium: De Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) broth or agar [17] [23].

- Inoculum Preparation: Transfer isolated colonies into sterile MRS broth and incubate at 37°C for 24 hours to create the seed culture [23].

Optimization of Production Conditions

A Box-Behnken Design (BBD), a type of RSM, is employed to optimize key parameters:

- Factors and Levels:

- Temperature: Test a range (e.g., 30-37°C). Optimal found at 35°C for L. plantarum and 37°C for L. rhamnosus [17] [23].

- Initial pH: Test a range (e.g., 6.5-7.0). Optimal found at pH 6.5 for L. plantarum and pH 7.0 for L. rhamnosus [17] [23].

- Incubation Time: Test a range (e.g., 48-72 hours). Optimal found at 48 hours for L. plantarum [17].

Bacteriocin Harvest and Activity Assay

- Harvest: Centrifuge the fermentation broth (e.g., 8,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C) and filter the cell-free supernatant through a 0.22 µm membrane [23].

- Antimicrobial Activity: Use the well diffusion assay or a dilution method in a microtiter plate [23].

- For the dilution method, bacteriocin activity (Arbitrary Units, AU/mL) is calculated as:

AU/mL = (1000 / 125) × (1 / HD), where HD is the highest dilution showing inhibition of the indicator strain [23].

- For the dilution method, bacteriocin activity (Arbitrary Units, AU/mL) is calculated as:

- Characterization: Treat the neutralized supernatant with protease to confirm the proteinaceous nature of the active compound [23].

Key Data and Optimization Results

Table 2: Optimized Bacteriocin Production Conditions for Lactobacillus Strains

| Parameter | L. plantarum [17] | L. rhamnosus CW40 [23] | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal Temperature | 35 °C | 37 °C | Strain-specific preferences |

| Optimal Initial pH | 6.5 | 7.0 | pH is a critical factor |

| Optimal Incubation Time | 48 h | Not Specified | |

| Maximum Activity | >10-fold increase | 4,098 AU/mL vs. E. coli | Confirmed peptide nature |

| Significant Factor | Initial pH | Not Specified | 95% confidence level |

Workflow Diagram: Lactobacillus Bacteriocin Production

Application Note & Protocol 3: Recombinant E. coli for CHMO Production

Background and Objective

Cyclohexanone monooxygenase (CHMO) from E. coli is a valuable biocatalyst for performing Baeyer-Villiger oxidations. This protocol focuses on optimizing the growth and induction conditions for recombinant E. coli BL21(DE3)(pMM04) to maximize whole-cell CHMO specific activity [24] [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Strain, Media, and Growth Conditions

- Production Strain: E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring plasmid pMM04 encoding CHMO from Acinetobacter sp. [24].

- Media: Use Terrific Broth (TB) for high-density growth [24].

- Growth Monitoring: Cultivate at 37°C with orbital mixing (210 rpm). Monitor growth by measuring dry cell concentration [24].

Optimization of Oxygen Mass Transfer

- The volumetric oxygen mass transfer coefficient (kLa) is a critical parameter.

- Calculate the maximal oxygen transfer rate (OTRₘₐₓ) using the provided equation [24].

- Aim for a kLa of 31 h⁻¹ to ensure aerobic growth is not limited by dissolved oxygen [24] [25].

Optimization of Induction Parameters

- Induction Timing: Induce during the exponential growth phase. A 5-hour cultivation period at kLa = 31 h⁻¹ is optimal, yielding a biocatalyst concentration of ~1 g/L [24] [25].

- Induction Agent: Use Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG).

- IPTG Concentration: A low-level induction of 0.16 mmol/L is optimal to maximize specific activity and minimize metabolic stress or inclusion body formation [24] [25].

- Induction Duration: A short induction period of 20 minutes is sufficient [24] [25].

- Temperature & pH: Post-induction, a lower temperature (25-30°C) and neutral pH (7.2-8.0) are recommended for functional protein expression and stability [24].

Biocatalyst Application

- Use the cells as resting cells (metabolically active but non-growing) in biotransformations [24].

- For sustained activity, employ repeated batch experiments with cell washing between cycles, which can maintain CHMO activity at 53 U/g over multiple cycles [24] [25].

Key Data and Optimization Results

Table 3: Optimized Conditions for Recombinant E. coli CHMO Production

| Parameter | Pre-Optimization | Optimized Condition | Impact on Specific Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| kLa Coefficient | Not Specified / Limiting | 31 h⁻¹ | Eliminates oxygen limitation |

| Induction Point | Not Specified | Exponential Phase (5h cultivation) | Highest specific activity |

| IPTG Concentration | Not Specified | 0.16 mmol/L (Low-level) | Prevents stress & inclusion bodies |

| Induction Duration | Not Specified | 20 minutes | Sufficient for high yield |

| Specific Activity | Baseline | 54.4 U/g | >130% improvement |

Workflow Diagram: Recombinant E. coli CHMO Production

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bacterial Production Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ISP2 Medium | Culture medium for growth and metabolite production of Streptomyces | Initial growth and pigment production in Streptomyces sp. MFB27 [18] |

| MRS Broth/Agar | Selective growth medium for cultivation of Lactobacillus strains | Isolation and growth of L. rhamnosus CW40 for bacteriocin production [23] |

| Terrific Broth (TB) | High-density growth medium for recombinant protein expression in E. coli | Biomass production for CHMO expression in E. coli BL21(DE3) [24] |

| Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) | Chemical inducer for protein expression under T7/lac promoter systems | Induction of CHMO expression in recombinant E. coli [24] [25] |

| Plackett-Burman & Box-Behnken Designs | Statistical designs for screening and optimizing significant factors | Identifying key media components and optimizing their levels via RSM [22] [17] |

| Ethyl Acetate | Organic solvent for extraction of secondary metabolites | Extraction of pigment-rich fractions from Streptomyces parvulus culture supernatants [26] |

| BugBuster Protein Extraction Reagent | Reagent for gentle lysis of bacterial cells to extract soluble proteins | Cell disruption for protein analysis in E. coli [24] |

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) has emerged as a powerful statistical and mathematical framework for optimizing complex bioprocesses, particularly in the realm of antibacterial production. This methodology enables researchers to efficiently model and analyze the relationship between multiple critical process parameters (CPPs) and desired antibacterial output, while quantifying interaction effects that traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches would miss [5] [27]. The application of RSM allows for the identification of optimal operating conditions with a reduced number of experiments, conserving both time and valuable resources [28]. This Application Note provides a comprehensive protocol for implementing RSM to systematically identify and optimize CPPs—specifically temperature, pH, inducer concentration, and medium components—to enhance the production of antibacterial compounds from microbial systems. The structured approach outlined herein is validated through case studies demonstrating successful optimization of antibiotic production from Streptomyces species and antibacterial metabolite production from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum [17] [28] [29].

Theoretical Framework of Response Surface Methodology

RSM utilizes statistical experimental designs to build empirical models that describe how input variables influence a response of interest. The general second-order polynomial model employed in RSM is expressed as:

y = β₀ + ∑βᵢxᵢ + ∑βᵢᵢxᵢ² + ∑βᵢⱼxᵢxⱼ + ε [5]

Where:

- y represents the predicted response (e.g., antibiotic yield, zone of inhibition)

- β₀ is the constant coefficient

- βᵢ are the linear effect coefficients

- βᵢᵢ are the quadratic effect coefficients

- βᵢⱼ are the interaction effect coefficients between variables

- xᵢ and xⱼ are the coded independent variables (CPPs)

- ε is the associated experimental error

This model successfully captures linear, quadratic, and interactive effects of process parameters on the production output, thereby facilitating the identification of optimal conditions [5] [27]. The model's validity is typically assessed through Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), with key indicators including a high coefficient of determination (R²), a significant model F-value, and a non-significant lack of fit [28].

Experimental Protocol for RSM-Based Optimization

Preliminary Screening of Critical Process Parameters

Purpose: To identify which factors (temperature, pH, inducer concentration, and medium components) exert significant influence on antibacterial production for inclusion in comprehensive RSM optimization.

Procedure:

- Define Factor Ranges: Establish physiologically relevant ranges for each potential CPP based on literature and preliminary studies. For bacterial fermentations, typical ranges are: temperature (25-45°C), pH (5.0-8.5), and incubation time (24-96 hours) [17] [27].

- Employ Screening Design: Utilize a Plackett-Burman design (PBD) to efficiently screen for significant factors. This design evaluates k factors in k+1 experiments, making it highly resource-efficient for initial screening [30].

- Conduct Experiments & Analyze: Perform fermentation experiments according to the PBD matrix. Quantify antibacterial production via zone of inhibition assays or quantitative methods like HPLC. Subject the data to statistical analysis to identify factors with confidence levels >90% for advancement to RSM optimization [30].

Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology

Purpose: To determine the optimal levels and interactions of the screened CPPs for maximizing antibacterial compound production.

Procedure:

- Select RSM Design:

- Box-Behnken Design (BBD): A three-level design suitable for 3-7 factors, requiring fewer runs than Central Composite Design (CCD) when the number of factors is modest [17] [30].

- Central Composite Design (CCD): A robust, five-level design that provides high-quality predictions across the experimental space, ideal for detailed optimization [27].

Execute Experimental Runs: Perform fermentation experiments as per the selected design matrix. Maintain strict control over all non-varying parameters during the process.

Response Quantification:

- Antibacterial Titer: Use agar diffusion bioassays against target pathogens (e.g., Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus). The zone of inhibition (IZ) in millimeters is a standard measure of antibiotic potency [28] [30].

- Biomass Measurement: Track cell growth (OD₆₀₀) or dry cell weight to correlate production with microbial growth [27].

- Metabolite Concentration: Employ chromatographic methods (e.g., HPLC, UHPLC) for precise quantification of specific antibacterial compounds [31].

Model Fitting and Validation:

- Input response data into statistical software (e.g., Design-Expert, Minitab) to perform regression analysis and generate a quadratic model.

- Validate the model's predictive accuracy by conducting confirmation experiments under the identified optimal conditions and comparing predicted versus actual results [28].

Case Studies and Data Presentation

Case Study 1: Optimization of Paromomycin Production byStreptomyces rimosus

In this study, RSM was employed to optimize paromomycin production under solid-state fermentation conditions. A D-optimal design was utilized to investigate three CPPs [28].

Table 1: RSM Optimization Results for Paromomycin Production

| Factor | Low Level | High Level | Optimal Level | Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.0 | 9.0 | 8.5 | < 0.05 (Significant) |

| Temperature (°C) | 25 | 35 | 30 | < 0.05 (Significant) |

| Inoculum Size (% v/w) | 1 | 10 | 5 | > 0.05 (Not Significant) |

The optimization resulted in a 4.3-fold enhancement in paromomycin concentration, reaching 2.21 mg/g of initial dry solids, confirming the efficacy of RSM in antibiotic production optimization [28].

Case Study 2: Optimization of Antibacterials fromLactiplantibacillus plantarum

This research applied RSM with a Box-Behnken design to maximize the production of antibacterials, including bacteriocins [17].

Table 2: Optimal Conditions for Antibacterial Production by L. plantarum

| Critical Process Parameter | Optimal Value | Contribution to Process |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 35 °C | Maximizes bacterial growth and metabolite synthesis |

| pH | 6.5 | Primary influencing factor (95% confidence); optimal for enzyme activity and stability |

| Incubation Time | 48 hours | Allows complete growth cycle and secondary metabolite production |

Implementation of these optimized conditions led to a more than 10-fold increase in the titer of antibacterials, a markedly superior improvement compared to non-optimized approaches [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Antibacterial Production Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Starch | Carbon/Energy Source | Enhanced antibiotic production in Streptomyces sp. SD1 [29] |

| Soya Peptone | Nitrogen Source | Optimization of bioactive metabolites in Nocardiopsis litoralis [27] |

| KBr (Potassium Bromide) | Inducer/Precursor | Significant effect on antibiotic production in Streptomyces sp. JAJ06 [30] |

| CaCO₃ | pH Buffer/Regulator | Maintained optimal pH during fermentation; significant effect on yield [30] |

| MgSO₄ | Enzyme Cofactor/Mineral | Enhanced antibiotic production in Streptomyces sp. SD1 [29] |

| Green Gram Husk | Solid Substrate | Served as effective, cost-effective substrate for Streptomyces sp. SD1 [29] |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram Title: RSM Optimization Workflow

Diagram Title: CPPs Influence on Antibacterial Production

The strategic application of Response Surface Methodology provides an efficient, systematic framework for identifying and optimizing critical process parameters in antibacterial production. Through careful experimental design and statistical analysis, researchers can precisely determine the complex interactions between temperature, pH, inducer concentration, and medium components that maximize yield and productivity. The protocols and case studies presented in this Application Note demonstrate that RSM-driven optimization can achieve substantial improvements—ranging from 4.3-fold to over 10-fold increases in antibacterial production [17] [28]. This methodology not only enhances production efficiency but also contributes to more sustainable processes through reduced resource consumption and waste generation [28]. For researchers in pharmaceutical development and industrial biotechnology, adopting RSM represents a critical step toward robust, optimized, and scalable antibacterial production processes.

Designing and Executing a Successful RSM Experiment for Antibacterial Production

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is a powerful collection of statistical and mathematical techniques for developing, improving, and optimizing processes in various scientific fields, including antibacterial production and environmental remediation. When researchers need to find the optimal conditions for a process influenced by multiple variables, RSM provides an efficient framework for modeling and analysis. The methodology is particularly valuable for understanding complex interactions between independent variables (such as temperature, pH, or concentration) and the resulting response (such as antibacterial yield or pollutant removal efficiency). RSM enables researchers to achieve several key objectives: identifying optimal factor levels for desired responses, understanding interaction effects between variables, developing comprehensive mathematical models for prediction, and reducing the total number of experiments required compared to traditional one-variable-at-a-time approaches.

The fundamental principle of RSM involves fitting a polynomial model to experimental data, typically represented by the equation: y = β₀ + ∑βᵢxᵢ + ∑βᵢᵢxᵢ² + ∑βᵢⱼxᵢxⱼ + ε where y represents the predicted response, β₀ is the constant coefficient, βᵢ represents the linear coefficients, βᵢᵢ represents the quadratic coefficients, βᵢⱼ represents the interaction coefficients, xᵢ and xⱼ are the independent variables, and ε is the random error term. This second-order model can capture curvature in the response surface, allowing for the identification of optimal regions within the experimental space.

Among the various designs available within RSM, Central Composite Design (CCD) and Box-Behnken Design (BBD) have emerged as the two most prominent and widely applied approaches for optimization studies. Both designs offer distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different experimental scenarios encountered in antibacterial research and development.

Comparative Analysis: CCD versus BBD

Core Structural Differences and Key Characteristics

Central Composite Design (CCD) and Box-Behnken Design (BBD) differ fundamentally in their structural composition and experimental requirements. Understanding these core differences is essential for selecting the most appropriate design for a specific antibacterial optimization study.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of CCD and BBD

| Characteristic | Central Composite Design (CCD) | Box-Behnken Design (BBD) |

|---|---|---|

| Design Points | Factorial points (2ᵏ), axial points (2k), center points (n₀) [32] | Edge midpoints, center points [33] |

| Variable Levels | Five levels (-α, -1, 0, +1, +α) [34] | Three levels (-1, 0, +1) [35] |

| Experimental Space | Spherical with extended axial points [32] | Spherical within cube [33] |

| Sequentiality | Sequential building on factorial design | Stand-alone design |

| Factor Range Exploration | Extended beyond factorial range | Limited to factorial range |

| Center Points | 3-6 replicates recommended [32] | 3-5 replicates recommended [33] |

| Number of Runs (k=3) | 15-20 experiments [32] [34] | 15 experiments [33] [35] |

CCD consists of three distinct components: a two-level full factorial or fractional factorial design (2ᵏ points), axial points (2k points) positioned at a distance α from the center, and multiple center points (n₀). The axial points allow CCD to explore regions beyond the original factorial range, providing additional information about curvature in the response surface. The value of α is carefully chosen to ensure rotatability, a desirable property that provides consistent prediction variance at all points equidistant from the design center. For three factors, a typical CCD requires 15-20 experimental runs, including 6-8 center points [32] [34].

In contrast, BBD is a spherical, rotatable design composed of three interlocking factorial designs with all points lying on the surface of a sphere. The design is formed by combining two-level factorial designs with incomplete block designs, resulting in points positioned at the midpoints of the edges of the process space and multiple center points. For three factors, BBD typically requires 15 experiments, making it more efficient than CCD in terms of the number of required runs [33] [35]. BBD does not include corner points (the ±1, ±1, ±1 combinations), which can be advantageous when these extreme conditions are impractical or impossible to implement in experimental settings.

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

Table 2: Advantages and Limitations of CCD and BBD

| Design | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| CCD | - Can estimate full quadratic models- Sequential approach builds on previous factorial designs- Extended axial points provide better estimation of pure quadratic terms- Covers wider experimental region- Excellent for exploring new processes with unknown optimal regions [32] [34] [36] | - Requires more experimental runs- Five levels for each factor increase complexity- Axial points may be impractical or impossible to achieve in some systems- Not suitable when corner points are hazardous or expensive |

| BBD | - Fewer required experimental runs- Three levels reduce operational complexity- Avoids extreme conditions at corners of cube- Spherical design provides good estimation capability- Ideal for processes where extreme conditions should be avoided [33] [35] | - Cannot estimate full cubic models- Non-sequential design- Limited to spherical experimental regions- May not efficiently explore corner regions of factor space |

The selection between CCD and BBD depends heavily on the specific research context, constraints, and objectives. CCD is particularly advantageous when researchers need to explore a wide experimental region or when the approximate location of the optimum is unknown. The sequential nature of CCD allows researchers to begin with a simple factorial design and augment it with axial points if curvature is detected, making it efficient for sequential learning about a process. This design excels in situations where the experimental region of interest is large or cuboidal rather than spherical.

BBD offers significant advantages when the experimental region of interest is spherical, and the researcher wishes to avoid extreme factor level combinations due to practical constraints, safety concerns, or cost considerations. The reduced number of required runs makes BBD particularly attractive when experiments are expensive, time-consuming, or resource-intensive. This efficiency has made BBD popular in biological studies, including antibacterial production optimization, where experimental runs may involve complex culturing processes or expensive reagents [33].

Application Protocols for Antibacterial Production Optimization

Central Composite Design Protocol for Biomass Production

The following protocol outlines the application of CCD for optimizing physical parameters to maximize biomass production of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), based on established methodology from scientific literature [32].

Phase 1: Experimental Design and Setup

- Define Factors and Levels: Identify critical independent variables and their ranges. For Hib biomass optimization, the factors were initial pH (5.15-9.25), agitation (100-300 rpm), and temperature (33.6-40.0°C) [32].

- Design Matrix Construction: Apply CCD with α = 1.682 (for rotatability) and 6 center points, generating 20 experimental runs. The design includes factorial points (coded ±1), axial points (coded ±α), and center points (coded 0).

- Randomization: Randomize the run order to minimize effects of extraneous variables.

Phase 2: Experimental Execution

- Culture Preparation: Prepare culture medium according to standardized formulations [32]. For Hib, this includes β-NAD, protoporphyrin IX, glucose, dialyzed yeast extract, cysteine, bactopepton, tryptophan, phosphates, and salts dissolved in deionized water.

- Inoculation Procedure:

- Thaw frozen Hib stock (ATCC 10211) and transfer to chocolate agar-slant tubes.

- Incubate at 37°C for 18 hours.

- Harvest bacteria and resuspend in culture medium.

- Transfer to fresh medium and incubate at 300 rpm, 37°C for 6-8 hours.

- Inoculate experimental flasks with 5 mL of this culture per 45 mL medium [32].

- Parameter Adjustment: Adjust each experimental flask to designated pH, agitation, and temperature conditions according to the design matrix.

- Incubation: Incubate flasks for 19 hours under specified conditions.

Phase 3: Response Measurement and Analysis

- Biomass Quantification:

- Heat-deactivate cultures at 60°C for 30 minutes.

- Centrifuge at 3200 × g for 60 minutes at 4°C in pre-weighed tubes.

- Discard supernatant, resuspend pellets in 0.15M NaCl, and centrifuge again.

- Dry tubes at 60°C for 24 hours and measure dry cell weight [32].

- Data Analysis:

- Fit experimental data to a second-order polynomial model.

- Perform ANOVA to assess model significance and lack-of-fit.

- Identify significant factors and interaction effects through p-values (typically <0.05).

- Generate response surface plots to visualize factor interactions.

- Optimization and Validation:

- Determine optimal factor levels using desirability functions.

- Confirm model predictions with validation experiments under optimal conditions.

CCD Experimental Workflow

Box-Behnken Design Protocol for Antibacterial Production

This protocol details the application of BBD for optimizing antibacterial production by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, adapted from established research methodologies [33].

Phase 1: Experimental Design

- Factor Selection: Identify critical process variables and their ranges. For L. plantarum antibacterial production, key factors include temperature (25-35°C), initial pH (5.5-7.5), and incubation time (24-72 hours) [33].

- Design Matrix: Construct BBD with three factors at three levels, requiring 15 experimental runs including three center points.

- Randomization: Randomize the experimental run order to minimize bias.

Phase 2: Culture Conditions and Antibacterial Production

- Inoculum Preparation:

- Revitalize L. plantarum strain on appropriate agar medium.

- Prepare pre-culture by inoculating single colony in liquid medium.

- Incubate overnight at optimal growth temperature.

- Experimental Cultivation:

- Inoculate production medium with standardized inoculum size (e.g., 2% v/v).

- Incubate cultures according to designed conditions of temperature, pH, and time.

- Maintain constant pH using appropriate buffering systems or pH controllers.

- Sample Harvesting:

- Collect samples at designated time points.

- Separate cells from supernatant by centrifugation (e.g., 10,000 × g, 10 minutes, 4°C).

- Filter-sterilize supernatant (0.22 μm membrane) for antibacterial activity assessment.

Phase 3: Antibacterial Activity Assessment

- Bioassay Preparation:

- Select indicator strains (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli).

- Prepare fresh cultures of indicator strains to mid-log phase.

- Activity Measurement:

- Use agar well diffusion or microdilution methods.

- For agar diffusion: Create wells in seeded agar plates, add cell-free supernatants, incubate, measure inhibition zones.

- For microdilution: Prepare serial dilutions of supernatants in microtiter plates, add indicator strain, incubate, measure optical density or use tetrazolium dyes for viability assessment.

- Activity Quantification: Express antibacterial activity as percentage reduction of pathogen viability or as arbitrary units per mL based on standard curves.

Phase 4: Data Analysis and Optimization

- Model Development: Fit response data to second-order polynomial model.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform ANOVA to identify significant model terms.

- Optimization: Determine optimal culture conditions for maximizing antibacterial production using response surface plots and desirability functions.

- Validation: Confirm model predictions with experimental runs under optimal conditions.

BBD Experimental Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of RSM for antibacterial optimization requires specific reagents, materials, and analytical tools. The following table summarizes key research reagent solutions essential for conducting these optimization studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Antibacterial Optimization Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Microbiological Materials | Bacterial strains (H. influenzae ATCC 10211, L. plantarum, pathogen indicators) [32] [33] | Target microorganisms for optimization studies and indicator strains for bioassays |

| Culture Media Components | β-NAD, protoporphyrin IX, glucose, yeast extract, cysteine, peptones, salts, buffers [32] | Support growth and production capabilities of target microorganisms |

| Process Parameter Controls | pH buffers and adjusters (NaOH, HCl), temperature control systems, agitation equipment [32] [33] | Maintain and manipulate critical process parameters during cultivation |

| Analytical Tools and Reagents | Centrifuges, spectrophotometers, HPLC systems, agar for diffusion assays, tetrazolium salts for viability assays [32] [33] | Quantify biomass, antibacterial activity, and metabolic products |

| Statistical Software | MODDE, Design Expert, Minitab, Chemoface, R with appropriate packages [34] [37] [35] | Experimental design generation, data analysis, model fitting, and optimization |

The selection between Central Composite Design and Box-Behnken Design represents a critical methodological decision in the optimization of antibacterial production processes. CCD offers comprehensive exploration of the experimental space with enhanced capacity for detecting curvature, making it ideal for preliminary studies where the optimal region is unknown. Conversely, BBD provides exceptional efficiency with fewer experimental runs while avoiding potentially problematic extreme conditions, making it particularly suitable for resource-constrained environments or when dealing with sensitive biological systems.

Both methodologies have demonstrated significant success in various antibacterial optimization contexts. CCD enabled the optimization of Haemophilus influenzae type b cultivation, achieving a dry biomass production of approximately 5470 mg/L under optimal conditions of pH 8.5, 35°C, and 250 rpm agitation [32]. Similarly, BBD facilitated the optimization of antibacterial production by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, resulting in more than a 10-fold increase in antibacterial concentration under optimal conditions of 35°C, pH 6.5, and 48 hours incubation [33].

The implementation of these methodologies extends beyond academic research to practical applications in pharmaceutical development, bio-preservative production, and environmental remediation. By applying the structured protocols outlined in this document and selecting the appropriate experimental design based on specific research constraints and objectives, scientists and drug development professionals can significantly enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of their antibacterial optimization efforts.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Factor Screening and Defining the Experimental Region

In the field of antibacterial production optimization, Response Surface Methodology (RSM) has emerged as a powerful collection of statistical and mathematical techniques for developing, improving, and optimizing processes [1]. This empirical modeling approach enables researchers to relate multiple input variables (factors) to one or more response variables, thereby identifying optimal operational conditions for maximizing antibacterial metabolite production [38]. The methodology was pioneered by George E. P. Box and K. B. Wilson in 1951 and has since been widely applied across various scientific disciplines, including pharmaceutical development, biotechnology, and antimicrobial production [38] [17].

The initial stages of any RSM study—factor screening and defining the experimental region—are particularly critical as they establish the foundation for all subsequent experimentation. These preliminary steps ensure that resources are focused on the most influential factors and that the experimental domain adequately captures the system's behavior, ultimately leading to more reliable optimization [39]. Within the context of antibacterial research, proper experimental region definition has enabled significant advances, such as the more than 10-fold increase in antibacterial production from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum through RSM optimization [17].

This protocol provides a detailed, step-by-step guide to factor screening and defining the experimental region, specifically framed within antibacterial production optimization research. We will explore practical methodologies for identifying significant variables and establishing appropriate factor levels, using real-world antimicrobial production case studies to illustrate key concepts and applications.

Theoretical Foundation

The RSM Framework and Sequential Experimentation

Response Surface Methodology operates within a structured framework of sequential experimentation, where each phase builds upon knowledge gained from previous experiments [1]. The overall approach typically follows these stages:

- Factor Screening: Identifying the few important factors from many potential candidates

- Defining the Experimental Region: Establishing appropriate ranges for these factors

- Response Surface Modeling: Developing empirical models relating factors to responses

- Optimization: Finding factor settings that produce desirable response values

This sequential approach is particularly valuable in antibacterial production optimization, where numerous factors—including temperature, pH, incubation time, and media components—may influence metabolite yield [17] [40]. For example, in optimizing fermentation conditions for Streptomyces sp. 1-14, researchers employed RSM to enhance antibacterial metabolite production against Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. cubense race 4, resulting in a 12.33% increase in antibacterial activity compared to pre-optimization conditions [40].

Key Statistical Concepts

The statistical foundation of RSM relies on several key concepts:

- Experimental Design: Systematic methods for planning experiments to efficiently collect data [1]

- Regression Analysis: Techniques for modeling the relationship between factors and responses [1]

- Model Validation: Procedures for evaluating model adequacy and predictive capability [39]

The primary mathematical model used in RSM is typically a second-order polynomial, expressed as:

Where:

- y is the predicted response

- β₀ is the constant term

- βᵢ are the linear coefficients

- βᵢᵢ are the quadratic coefficients

- βᵢⱼ are the interaction coefficients

- xᵢ and xⱼ are the coded independent variables

- ε is the random error term [5] [41]

This model successfully captures linear, quadratic, and interaction effects between factors, providing a comprehensive representation of the response surface within the defined experimental region.

Preliminary Steps: Laying the Groundwork

Problem Definition and Response Selection

Before embarking on factor screening, clearly define the research objective and identify the critical response variables to optimize. In antibacterial production, this typically involves:

- Primary Response: Often the yield or potency of the antibacterial metabolite [40]

- Secondary Responses: May include growth metrics, process efficiency, or cost parameters [17]

Table 1: Common Response Variables in Antibacterial Production Optimization

| Response Variable | Measurement Method | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Antibacterial Activity | Agar diffusion assay, MIC determination | Inhibition zone against target pathogens [40] |

| Metabolite Yield | HPLC, GC-MS | Quantification of specific antimicrobial compounds [17] |

| Biomass Concentration | Dry cell weight, optical density | Microbial growth assessment [40] |

| Process Efficiency | Yield coefficient, productivity | Economic viability assessment [39] |

Initial Factor Identification

Comprehensive literature review and prior knowledge guide the compilation of all potential factors that might influence the response variables. For antibacterial production, this typically includes:

- Physical Factors: Temperature, pH, incubation time, agitation speed [17]

- Media Components: Carbon sources, nitrogen sources, minerals, inducers [40]

- Process Parameters: Inoculum size, aeration, fermentation strategy [40]

In a study on Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, initial factor identification included temperature, pH, and incubation time, with pH subsequently emerging as the most significant factor influencing antibacterial production [17].

Step-by-Step Protocol for Factor Screening

Factor screening aims to identify the few significant factors from many potential candidates, allowing researchers to focus resources on the most influential variables. The following workflow illustrates the sequential nature of factor screening in the RSM framework:

Protocol: Plackett-Burman Design for Factor Screening

Plackett-Burman (PB) designs are highly efficient for screening multiple factors with a minimal number of experimental runs [40]. These designs assume that interactions between factors are negligible compared to main effects, making them ideal for initial screening phases.

Materials and Equipment

- Experimental apparatus appropriate for antibacterial production (e.g., bioreactor, shake flasks)