Innovative Strategies for Biofilm Disruption in Persistent Infections: From Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current and emerging strategies to combat biofilm-associated persistent infections, which are responsible for 65-80% of all human microbial diseases and exhibit up...

Innovative Strategies for Biofilm Disruption in Persistent Infections: From Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current and emerging strategies to combat biofilm-associated persistent infections, which are responsible for 65-80% of all human microbial diseases and exhibit up to 1000-fold increased antibiotic resistance. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the complex biofilm lifecycle and resistance mechanisms, evaluates disruptive technologies including enzymatic agents, quorum sensing inhibitors, and nanoparticle-based delivery systems, addresses translational challenges from laboratory to clinical settings, and compares the efficacy of conventional versus novel therapeutic approaches. The synthesis of foundational science with applied clinical perspectives aims to bridge critical knowledge gaps and accelerate the development of effective anti-biofilm therapeutics.

Understanding Biofilm Pathogenesis: Architecture, Resistance Mechanisms, and Clinical Impact

Bacterial biofilms are complex, structured communities of microorganisms encased in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. They are a predominant form of microbial life and play a significant role in persistent infections, contributing to an estimated 65-80% of all human microbial infections [1]. The classic understanding of the biofilm lifecycle depicted a linear, five-stage process: reversible attachment, irreversible attachment, maturation I, maturation II, and dispersion [2]. However, contemporary research emphasizes that this model, largely based on in vitro studies of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, does not fully capture the diversity of biofilm development, especially in clinical, industrial, and natural environments [2] [1].

An expanded, more inclusive model conceptualizes the biofilm lifecycle around three core processes: aggregation, growth, and disaggregation [2] [1]. This model accommodates both surface-attached biofilms and non-surface-attached aggregates, which are now recognized as critical in many chronic infections, such as those in the viscous airway mucus of cystic fibrosis patients or in non-healing wounds [2]. Understanding this dynamic lifecycle is fundamental to developing effective strategies for biofilm disruption in persistent infections research.

Core Concepts and Definitions

To ensure clarity in troubleshooting and experimental design, the following definitions are provided [2]:

- Biofilm: A microbial aggregate attached to a surface or existing as a non-surface-attached aggregate, embedded in an extracellular matrix.

- Aggregation: Any biological, chemical, or physical process that allows microbial cells to form a cohesive group. This includes microbial growth, autoaggregation, and polymer depletion aggregation.

- Adherence/Attachment: The process by which suspended single cells or aggregates stick to a biotic or abiotic surface.

- Accumulation: The net result of attachment, aggregation, growth, disaggregation, and detachment processes that lead to the expansion or shrinkage of a biofilm.

- Disaggregation: The process by which aggregated cells, whether in suspension or surface-associated, shed smaller aggregates or individual cells into the fluid phase. This includes:

- Erosion: Loss of single cells or very small aggregates due to physical forces.

- Dispersal: A biologically regulated, active release of cells.

- Cohesive Fracture: The breakage of aggregates due to internal mechanical failure.

- Sloughing: The release of large, coherent layers of surface-attached biofilm.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Our anti-biofilm compound shows efficacy in microtiter plate assays but fails in more complex wound models. What could be the reason?

- Answer: This is a common translational challenge. Microtiter plate assays are valuable for high-throughput screening but are a significant simplification of in vivo conditions [3]. The failure likely stems from:

- Lack of Host Components: Simple models lack host-derived components like plasma, blood cells, and immune factors present in wound models (e.g., the Lubbock model), which can alter biofilm structure and increase tolerance to antimicrobials [3].

- Biofilm Maturity: Many in vitro models use 12-24 hour biofilms, whereas chronic wounds can harbor biofilms that are weeks old, exhibiting vastly different physiological states and resilience [3].

- 3D Architecture: Biofilms grown in 3D hydrogel models demonstrate different architecture and increased tolerance compared to 2D biofilms on plastic surfaces [3].

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Validate Early: Incorporate more relevant models early in the discovery pipeline.

- Use Multiple Models: Do not rely solely on microtiter plates. Use a tiered approach, progressing from simple to complex models (e.g., microtiter plate → CDC biofilm reactor → 3D hydrogel or tissue culture model) to confirm activity [3].

- Check Compound Compatibility: Ensure your compound is not inactivated by host components like serum albumin.

FAQ 2: How can we effectively visualize and differentiate the biofilm matrix from bacterial cells without access to advanced microscopy?

- Answer: Advanced techniques like Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) provide high-resolution images but are costly and complex [4] [5]. A recently developed, cost-effective alternative is the dual-staining method using Maneval's stain [5].

- Protocol: Dual-Staining with Maneval's for Biofilm Visualization [5]:

- Grow Biofilm: Grow biofilm on a sterile glass slide submerged in nutrient broth for 24-72 hours.

- Rinse: Gently rinse the slide in distilled water for 5 seconds to remove non-adhered cells.

- Fix: Fix the biofilm with 4% formaldehyde (in distilled water) for 15-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Stain with Congo Red: Apply 1% Congo red stain and allow it to air-dry completely.

- Stain with Maneval's: Treat the sample with Maneval's stain for 10 minutes.

- Visualize: Remove excess stain, air-dry, and observe under a light microscope with 100x oil immersion.

- Expected Outcome: Bacterial cells appear magenta-red, surrounded by a blue-stained polysaccharide biofilm matrix, allowing for clear differentiation [5].

FAQ 3: Why are biofilm-dispersing enzymes considered a promising strategy, and what are the main classes?

- Answer: Dispersing enzymes degrade the EPS that constitutes the protective shield of the biofilm. This strategy is promising because enzymes are highly specific, effective at low concentrations, and less likely to induce antibiotic resistance as they act extracellularly [1]. By breaking down the biofilm matrix, they revert protected sessile cells to a vulnerable planktonic state, making them susceptible to conventional antibiotics and host immune responses [1].

- The main enzyme classes and their targets are:

FAQ 4: What are the key reasons for the high antibiotic tolerance of biofilms, and how can our assays account for them?

- Answer: Biofilm tolerance is multifactorial. Your experimental models should be designed to probe these specific mechanisms [6] [1]:

- Physical Barrier: The EPS matrix can restrict antibiotic penetration.

- Metabolic Heterogeneity: Gradients of nutrients and oxygen within the biofilm create subpopulations of slow-growing or dormant persister cells that are highly tolerant to antibiotics [1].

- Altered Microenvironment: Conditions like low pH within the biofilm can neutralize some antibiotics.

- Troubleshooting Guide for Assay Design:

- Measure Penetration: Use fluorescently tagged antibiotics and CLSM to visualize penetration depth.

- Assay Metabolic State: Use probes like CTC for metabolic activity or stain for live/dead cells to identify heterogeneous zones.

- Test against Persisters: After antibiotic treatment, disrupt the biofilm physically and plate the cells to check for regrowth from dormant persister cells.

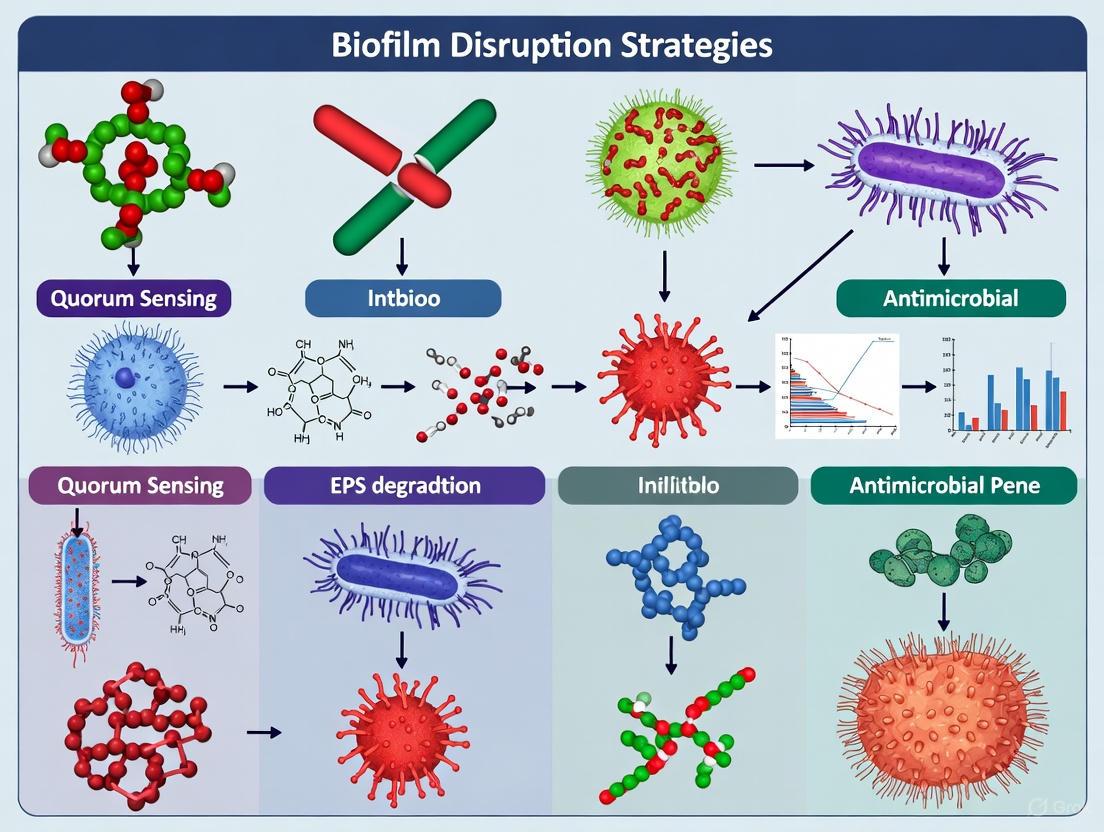

Key Signaling Pathways and Molecular Regulation

The transition from planktonic to biofilm growth is tightly regulated by molecular signaling. Two key systems are Quorum Sensing (QS) and the secondary messenger c-di-GMP.

Quorum Sensing (QS) Pathway

QS is a cell-cell communication process allowing bacteria to coordinate gene expression based on population density. This regulates collective behaviors, including biofilm formation and dispersal [7].

Diagram Title: Quorum Sensing Regulatory Pathway

c-di-GMP Signaling Pathway

Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) is a ubiquitous secondary messenger that acts as a central switch between motile and sessile lifestyles. High intracellular c-di-GMP promotes biofilm formation, while low levels favor dispersal and motility [6] [7].

Diagram Title: c-di-GMP Signaling Switch

Experimental Protocols for Biofilm Disruption

Protocol: Evaluating Biofilm Dispersal Enzymes

This protocol outlines a method for testing the efficacy of glycoside hydrolases, proteases, and DNases in disrupting pre-formed biofilms [1].

Workflow:

Diagram Title: Enzyme Dispersal Assay Workflow

Detailed Steps:

- Biofilm Growth: Grow a standardized biofilm (e.g., of Staphylococcus aureus or Pseudomonas aeruginosa) for 24-48 hours in a suitable model system (microtiter plate, Calgary device, or CDC biofilm reactor) [1].

- Enzyme Treatment: Gently wash the mature biofilm to remove non-adherent cells. Add the dispersal enzyme (e.g., DNase I, dispersin B, proteases) diluted in an appropriate buffer to the biofilm. Include a buffer-only negative control.

- Incubation: Incubate under optimal conditions for the enzyme (e.g., 37°C for 1-4 hours).

- Quantification of Dispersal:

- Crystal Violet Staining: Measure the remaining attached biomass after staining.

- ATP Assay: Measure the ATP content of dispersed cells in the supernatant as an indicator of released, viable biomass.

- Microscopy: Use light or confocal microscopy to visually confirm structural disintegration of the biofilm.

- Synergy with Antibiotics: Following enzyme treatment, add a conventional antibiotic to the system. Compare the reduction in viable cell counts (CFU/mL) between "antibiotic alone" and "enzyme + antibiotic" groups to demonstrate synergy.

Protocol: Advanced Microscopy for Anti-biofilm Evaluation (SEM)

SEM provides unparalleled image quality for assessing the ultrastructural effects of anti-biofilm treatments [4].

Key Steps:

- Fixation: Fix biofilm samples with a customized protocol, e.g., 2.5% glutaraldehyde, sometimes supplemented with ruthenium red or tannic acid to better preserve the EPS matrix [4].

- Dehydration: Dehydrate the sample through a graded ethanol series (e.g., 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 100%) [4] [5].

- Drying: Use critical point drying to avoid structural collapse from surface tension.

- Coating: Sputter-coat the sample with a thin layer of gold or another conductive material.

- Imaging and Analysis: Image the biofilm using SEM. Use image analysis software to extract quantitative parameters like biofilm coverage, roughness, or matrix thickness from the micrographs [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their applications in biofilm research.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Brief Explanation | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Maneval's Stain [5] | A cost-effective staining solution that differentially stains bacterial cells (magenta-red) and the polysaccharide matrix (blue). | Visualization and differentiation of biofilm components using light microscopy. |

| Crystal Violet [8] [5] | A basic dye that binds to negatively charged surface molecules and polysaccharides, quantifying total adhered biomass. | Basic, high-throughput quantification of biofilm biomass. Not suitable for viability assessment. |

| Dispersin B [1] | A glycoside hydrolase enzyme that specifically hydrolyzes the poly-N-acetylglucosamine (dPNAG) exopolysaccharide. | Enzymatic dispersal of biofilms formed by pathogens like S. aureus and E. coli. |

| Deoxyribonuclease I (DNase I) [1] | An enzyme that degrades extracellular DNA (eDNA), a critical structural component in many bacterial biofilms. | Disruption of biofilms where eDNA is a major matrix constituent; reduces biofilm integrity. |

| Calcofluor White [5] | A fluorescent dye that binds to polysaccharides containing β-linked glucans (e.g., cellulose). | Fluorescence-based visualization of specific exopolysaccharides in the biofilm matrix. |

| c-di-GMP [6] | A key bacterial second messenger; high intracellular levels promote biofilm formation, low levels induce dispersal. | A critical target for small molecules aimed at manipulating the biofilm lifecycle. |

Quantitative Data on Biofilm Resistance and Enzyme Efficacy

The tables below summarize key quantitative data relevant to biofilm challenges and therapeutic strategies.

Table 1: Biofilm-Associated Challenges in Healthcare

| Metric | Value | Context / Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Human Microbial Infections | 65 - 80% [1] | Highlights the clinical prevalence and importance of biofilms. |

| Estimated Global Economic Impact | ~$5 Trillion USD annually [3] | Includes health, food/water security, and industrial costs. |

| Chronic Wounds with Biofilms | 78.2% [3] | Systematic review finding, underscores role in chronicity. |

| Increased Antibiotic Tolerance | Up to 1000-fold [6] | Biofilm cells can be much more tolerant than planktonic cells. |

Table 2: Representative Biofilm-Dispersing Enzymes and Targets

| Enzyme Class | Example Enzyme | Target in EPS | Mechanism & Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycoside Hydrolase | Dispersin B [1] | dPNAG / PIA | Hydrolyzes β-1,6-glycosidic bonds in dPNAG, dissolving the structural scaffold for many staphylococcal and Gram-negative biofilms. |

| Protease | Proteinase K [1] | Matrix Proteins & Adhesins | Degrades proteinaceous components of the EPS and surface adhesins, disrupting biofilm integrity and attachment. |

| Deoxyribonuclease | DNase I [1] | extracellular DNA (eDNA) | Cleaves eDNA, which acts as a structural "glue" in many biofilms, leading to destabilization and dispersal. |

FAQ: Core Concepts and Composition

What is the primary function of the EPS matrix in bacterial biofilms? The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix is the fundamental component that establishes the functional and structural integrity of biofilms. It acts as a protective barrier, safeguarding microbial communities from harsh environmental conditions, including antibiotic attacks and host immune responses. The matrix provides mechanical stability, mediates interactions between cells, and is a source of nutrients and enzymes [9] [10]. Its complex structure limits the penetration of antimicrobial agents, contributing significantly to the high antibiotic tolerance observed in biofilm-based infections [10] [6].

What are the main chemical components of the EPS? The EPS is a complex, highly hydrated mixture of biomolecules, primarily consisting of polysaccharides, proteins, and extracellular DNA (eDNA). Other constituents include lipids and humic substances [9] [11]. The composition is not homogeneous and can vary significantly between different bacterial species and even between strains of the same species [10].

Table 1: Major Components of the Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS)

| Component Class | Key Subcategories | Primary Functions in the Biofilm Matrix |

|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharides | Exopolysaccharides (e.g., Alginate, Cellulose, Pel, Psl) | Form a scaffold and structural network; provide mechanical stability; act as a diffusion barrier; enable cell-surface and cell-cell interactions [9] [10] [6]. |

| Proteins | Structural proteins, Enzymes (e.g., proteases, glycosidases) | Stabilize biofilm architecture (structural proteins); degrade matrix components for nutrients and reorganization (enzymes) [10] [11]. |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | - | Contributes to structural integrity and stability; facilitates horizontal gene transfer, including antibiotic resistance genes [10] [11]. |

| Lipids & Other Molecules | Lipids, Lipopolysaccharides, Humic substances | Contribute to matrix structure and properties; can influence hydrophobicity and adhesion [9] [11]. |

How does the EPS matrix confer resistance to antibiotics? The EPS matrix contributes to antibiotic resistance through multiple, interconnected mechanisms [10] [6]:

- Physical Barrier: The dense matrix physically hinders the diffusion of antibiotic molecules into the deeper layers of the biofilm, preventing them from reaching bacteria at bactericidal concentrations.

- Chemical Deactivation: Antibiotics can interact with and be deactivated by EPS components through binding, chelation, or enzymatic degradation (e.g., by β-lactamases).

- Physiological Heterogeneity: The biofilm structure creates gradients of nutrients, oxygen, and waste products. This leads to zones where bacterial cells enter a slow-growing or dormant state, making them less susceptible to many antibiotics that target active cellular processes.

- Facilitated Resistance Gene Transfer: The close proximity of cells within the EPS matrix enhances the exchange of genetic material, such as plasmids carrying antibiotic resistance genes.

FAQ: Analytical and Methodological Approaches

How can I analyze the overall chemical composition of a biofilm? Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy is a valuable technique for the non-destructive analysis of biofilm composition. It detects specific molecular vibrations from functional groups, providing a spectral fingerprint of the main biomolecule classes present [11].

Table 2: Key FT-IR Spectral Windows for Biofilm Analysis

| Spectral Range | Primary EPS Components Detected | Corresponding Functional Groups |

|---|---|---|

| 2800–3000 cm⁻¹ | Lipids | C-H, CH₂, CH₃ |

| 1500–1800 cm⁻¹ | Proteins | C=O, N-H, C-N (Amide I, Amide II bands) |

| 900–1250 cm⁻¹ | Polysaccharides, Nucleic Acids | C-O, C-O-C, P=O |

What methodologies can be used to assess the functional role of specific EPS components? The sensitivity of biofilms to specific enzymatic treatments is a direct method to determine the functional importance of different EPS constituents. If an enzyme causes biofilm disruption, its target molecule is critical for matrix integrity [11].

Experimental Protocol: Enzymatic Disruption of Biofilms

- Biofilm Growth: Grow biofilms in suitable media under static or dynamic conditions on surfaces compatible with your assay (e.g., 96-well plates, silicone tubes).

- Enzyme Preparation: Prepare fresh solutions of enzymes in an appropriate buffer. Common examples include:

- Proteases (e.g., Savinase, Subtilisin A): Target protein components.

- Glycosidases (e.g., α-amylase): Target polysaccharide components.

- DNases (e.g., DNase I): Target extracellular DNA (eDNA).

- Treatment: Gently wash the mature biofilms to remove non-adherent cells. Add the enzyme solution to the biofilm and incubate at the optimal temperature for enzyme activity for a defined period (e.g., 24 hours).

- Analysis: Quantify the remaining biofilm using methods like:

- Crystal Violet (CV) Staining: Measures total adhered biomass.

- Colony Forming Unit (CFU) Counting: Quantifies viable bacteria.

- Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM): Visualizes live/dead bacteria and biofilm structure in 3D.

Experimental Guide: Advanced Biofilm Disruption Strategies

Combined Shockwave and Antibiotic Therapy

Recent research highlights the efficacy of combining physical disruption methods with antibiotics. The following protocol is adapted from a 2025 study investigating the disruption of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in tubular structures, a model relevant to catheter-associated infections [12].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Aim: To degrade biofilms on tubular structures and enhance subsequent antibiotic efficacy using shockwave treatment.

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: Pseudomonas aeruginosa (e.g., KCTC 22073)

- Growth Medium: Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) and Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA)

- Biofilm Substrate: Silicone tube (Inner diameter: 4 mm)

- Shockwave Source: Intravascular Lithotripsy (IVL) balloon catheter (e.g., Shockwave C2+)

- Antibiotic: Ciprofloxacin

- Staining Reagents: Crystal Violet (CV) solution, LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit (SYTO9/PI)

- Equipment: Peristaltic pumps, confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM), scanning electron microscope (SEM), sonication bath.

Procedure:

- Biofilm Formation:

- Circulate a diluted P. aeruginosa culture through the silicone tube system for 72 hours at 35°C using a pump.

- Continuously supply fresh TSB medium and air to promote robust biofilm growth [12].

- Treatment:

- Cut the biofilm-colonized tube into 3 cm long pieces.

- Shockwave Treatment: Place the sample in saline. Insert the IVL catheter and deliver shockwaves at 4 kV, 2 Hz for a total of 120 pulses (60 seconds).

- Antibiotic Treatment: Immediately after shockwave exposure, expose the biofilm to 4 µg/mL ciprofloxacin for 6 hours at 37°C.

- Analysis:

- Bacterial Viability:

- CFU Analysis: Sonicate and vortex treated samples to liberate bacteria, plate serial dilutions on TSA, and count colonies after 24h incubation.

- CLSM: Stain bacterial suspensions with SYTO9 (live, green) and PI (dead, red) to quantify live/dead ratios using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

- Biofilm Detachment:

- Crystal Violet Staining: Stain the tube, dissolve the dye in ethanol, and measure optical density at 600 nm to quantify remaining biomass.

- SEM: Fix, dehydrate, and critically point-dry biofilm samples to visualize the structural integrity of the matrix.

- Bacterial Viability:

Expected Results: The combined treatment is expected to show significantly greater biofilm detachment (e.g., >97% surface area removal) and reduced bacterial viability (e.g., 40% reduction in CFU, 67% dead bacteria) compared to antibiotic treatment alone [12].

Targeting Intracellular Signaling for Biofilm Inhibition

Another strategic approach involves targeting the intracellular secondary messenger c-di-GMP, which centrally regulates the transition from planktonic to biofilm lifestyle. High intracellular levels of c-di-GMP promote the production of EPS components and adhesins, reinforcing biofilm formation [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Biofilm Disruption Experiments

| Problem | Potential Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in disruption assays (e.g., CV staining). | Inconsistent biofilm growth between replicates. | Standardize growth conditions (inoculum size, medium, temperature, flow rate for dynamic systems). Use internal controls in every experiment. |

| Enzyme treatment shows no effect. | Enzyme is inactive or cannot access its substrate within the dense matrix. | Use fresh, high-purity enzymes and verify their activity. Increase treatment time or combine with other matrix-disrupting agents (e.g., chelators) to improve access. |

| Shockwave treatment damages the underlying substrate. | Excessive energy or pulse number. | Optimize shockwave parameters (voltage, pulse count) in preliminary tests specific to your biofilm model. |

| Antibiotic alone is ineffective even after physical disruption. | Persister cells or high levels of inherited resistance. | Combine antibiotics with different mechanisms of action. Consider using anti-biofilm agents that target persister cells. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biofilm EPS Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Proteases (e.g., Savinase, Subtilisin A) | Degrade protein components of the EPS matrix; assess protein's role in integrity. | Disruption of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus biofilms [11]. |

| Glycosidases (e.g., α-amylase, Dispersin B) | Target polysaccharide components; study exopolysaccharide function. | Inhibition and detachment of S. aureus biofilms [10] [6]. |

| DNase I | Degrades extracellular DNA (eDNA); investigates eDNA's structural role. | Destabilization of biofilms where eDNA is a major matrix component (e.g., P. aeruginosa) [10]. |

| Crystal Violet (CV) | Stains total adhered biomass; standard quantitative and visual assessment of biofilms. | Measuring biofilm formation and detachment after experimental treatments [12]. |

| LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit | Differentiates live (SYTO9, green) from dead (Propidium Iodide, red) cells via membrane integrity. | Confocal microscopy analysis of bactericidal effects after anti-biofilm treatment [12]. |

| Shockwave Intravascular Lithotripsy (IVL) Catheter | Generates high-pressure acoustic waves for the physical disruption of biofilm structure. | Loosening biofilm matrix on tubular structures to enhance antibiotic efficacy [12]. |

| Ciprofloxacin | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic; used to treat Gram-negative bacterial infections. | Assessing enhanced antibiotic killing following EPS disruption methods [12]. |

Molecular Mechanisms of Biofilm-Associated Antimicrobial Resistance

Within the context of developing strategies to disrupt persistent infections, understanding the molecular mechanisms of biofilm-associated antimicrobial resistance is a foundational prerequisite. Biofilms, which are structured communities of microorganisms encased in an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS), are a primary factor in chronic and recurrent infections [13]. Cells within a biofilm can exhibit a 10 to 1,000-fold increase in antibiotic resistance compared to their planktonic (free-floating) counterparts [14]. This dramatic tolerance makes biofilm-related infections—such as those associated with medical devices, cystic fibrosis lungs, and chronic wounds—notoriously difficult to treat [15] [16]. This technical resource details the core mechanisms behind this resistance and provides actionable experimental guidance for researchers in the field.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Core Concepts Explained

FAQ 1: What are the primary molecular mechanisms that drive antimicrobial resistance in biofilms? Biofilms employ a multi-layered defensive strategy that confers intrinsic resistance. The main mechanisms can be categorized as follows [14]:

- Physical Barrier: The EPS matrix, composed of exopolysaccharides, proteins, and extracellular DNA (eDNA), restricts the penetration of antimicrobial agents [15] [17].

- Metabolic Heterogeneity: Gradients of nutrients and oxygen within the biofilm create microenvironments where subpopulations of cells enter a slow-growing or dormant state, making them less susceptible to antibiotics that target active cellular processes [18] [1].

- Persister Cells: A small subpopulation of dormant bacterial cells, known as "persisters," exhibits extreme tolerance to antimicrobials. These cells are not genetically mutant but can repopulate the biofilm after antibiotic treatment is ceased [1] [17].

FAQ 2: How does the biofilm matrix physically impede antibiotic action? The EPS acts as a protective barrier through several interrelated processes [15] [19]:

- Diffration Limitation: The dense, anionic matrix physically slows down the diffusion of antimicrobial molecules into the deeper layers of the biofilm.

- Binding and Inactivation: Certain components of the matrix can directly bind and neutralize antibiotics. For example, positively charged aminoglycosides can be sequestered by negatively charged eDNA [15]. Additionally, enzymes like catalases within the matrix can inactivate antimicrobial molecules [17].

FAQ 3: What role does Quorum Sensing (QS) play in biofilm-associated resistance? Quorum Sensing is a cell-cell communication system that allows bacteria to coordinate gene expression based on population density. QS is a master regulator of biofilm development, including the production of the EPS matrix [13] [16]. By controlling biofilm maturation and architecture, QS indirectly contributes to the resistance phenotype. Disrupting QS signaling is therefore a key strategy being investigated for biofilm dispersal [20].

FAQ 4: Why are biofilms particularly problematic on medical devices? Medical devices, such as catheters and prosthetic joints, provide ideal abiotic surfaces for biofilm formation. It is estimated that approximately 65-80% of all human microbial infections are associated with biofilms, with a significant proportion being device-related [13] [1]. These biofilms act as a persistent source of infection, often requiring the removal of the device for successful treatment [13] [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

| Challenge | Potential Root Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in biofilm assays | Inconsistent inoculation; poorly controlled growth conditions (flow, temperature); surface properties of substrate. | Standardize pre-culture conditions; use controlled flow cells for consistent shear force; utilize reproducible surface coatings [15] [16]. |

| Unexpectedly low antibiotic tolerance in a known biofilm-forming strain | Biofilm not fully matured; incorrect antibiotic concentration or exposure time; over-aggressive washing during assay. | Extend biofilm growth time (e.g., 48-72 hrs); perform a Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC) assay; validate maturity via microscopy or EPS staining [18] [16]. |

| Failure to disrupt biofilm with a matrix-targeting enzyme (e.g., DNase, protease) | Enzyme activity is compromised; enzyme cannot access its substrate within the complex matrix; incorrect enzyme selection for the target biofilm. | Verify enzyme activity prior to use; pre-treat with a combination of enzymes (e.g., DNase + protease) to synergistically degrade the EPS; confirm the presence of the enzyme's target in your biofilm model [1]. |

| Inability to eradicate persister cells | Standard bactericidal antibiotics are ineffective against dormant persisters. | Combine antibiotics with agents that disrupt the membrane potential or target persistent cell metabolism; use sequential treatment strategies [1] [19]. |

Quantitative Data: Biofilm Resistance Metrics

Table 1: Documented Increases in Antimicrobial Resistance in Biofilm vs. Planktonic Cells.

| Bacterial Species | Antibiotic | Fold-Increase in Resistance (Biofilm vs. Planktonic) | Context / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Vancomycin | ~Infinite (100% susceptible to completely resistant in biofilm) | Clinical isolates from device-related infections [14]. |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Various | Up to 1000x | General observation for this common pathogen [14]. |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Tobramycin | Significantly decreased susceptibility | eDNA and host NETs form a protective shield in CF lung models [15]. |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Certain antibiotics | Highly resistant in biofilm, susceptible in planktonic state | Pattern observed in biofilm models [14]. |

Table 2: Key Enzymes for Experimental Biofilm Disruption.

| Enzyme Class | Target in EPS | Example Enzyme | Mechanism of Action in Biofilm Dispersal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycoside Hydrolases | Exopolysaccharides | Dispersin B | Hydrolyzes poly-β-1,6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (dPNAG), a key polysaccharide in many biofilms [1]. |

| Proteases | Protein adhesins & matrix proteins | Various proteases (e.g., Lysostaphin) | Degrades protein-based structural components and adhesins, destabilizing the biofilm architecture [1]. |

| Deoxyribonucleases (DNases) | Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | DNase I | Degrades the eDNA scaffold, which is crucial for biofilm structural integrity in many species [18] [1]. |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Assessing Biofilm Permeability to Antibiotics

Principle: To visualize and quantify the penetration and binding of an antibiotic within the biofilm matrix.

Materials:

- Fluorescently tagged antibiotic (e.g., Vancomycin-FL)

- Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM)

- Mature biofilm grown in a suitable chamber (e.g., flow cell or ibidi µ-Slide)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

Procedure:

- Grow a mature biofilm (e.g., 48-72 hours) under conditions relevant to your study.

- Gently wash the biofilm with PBS to remove non-adherent cells.

- Introduce a solution of the fluorescently tagged antibiotic at the desired concentration and incubate for a set time (e.g., 30-90 minutes).

- Carefully wash again with PBS to remove unbound antibiotic.

- Immediately image using CLSM. Use Z-stacking to capture the 3D distribution of the fluorescent signal throughout the biofilm depth.

- Troubleshooting Tip: If fluorescence is weak, confirm the activity of the tagged antibiotic and consider increasing the incubation time. Use controls to rule out non-specific binding [15].

Protocol 2: Generating and Isoling Persister Cells

Principle: To enrich for and isolate the dormant, antibiotic-tolerant persister cell subpopulation from a biofilm.

Materials:

- Mature biofilm

- High concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., Ciprofloxacin at 10-100x MIC)

- Centrifuge and microtubes

- Fresh growth medium

Procedure:

- Harvest a mature biofilm by gently scraping or sonicating at a low power to dislodge cells. Suspend in fresh medium.

- Treat the cell suspension with a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic for a prolonged period (e.g., 4-6 hours) to kill all non-persister cells.

- Centrifuge the treated suspension and carefully remove the supernatant containing the antibiotic.

- Wash the pellet twice with PBS to ensure antibiotic removal.

- Resuspend the pellet in fresh, antibiotic-free medium. The surviving cells are highly enriched for persisters.

- Troubleshooting Tip: Validate the success of the enrichment by plating the suspension on agar plates and comparing colony counts before and after antibiotic treatment. The persister-enriched population should show a significant reduction in viable count after treatment, with only a small fraction surviving [1] [17].

Visualization: Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram Title: Molecular Mechanisms of Biofilm-Associated Resistance

Diagram Title: Biofilm Dispersal Therapy Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Biofilm Resistance.

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Biofilm Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Flow Cells | Enables growth of biofilms under controlled, continuous-flow conditions that mimic natural environments. | Studying biofilm architecture via microscopy and real-time penetration assays [15]. |

| Congo Red Dye | Binds to exopolysaccharides like cellulose and dPNAG; used to visually identify matrix production. | Qualitative assessment of biofilm-forming capability of bacterial colonies on agar plates. |

| DNase I | Degrades extracellular DNA (eDNA), a critical structural component in many biofilms. | Experimental disruption of biofilms to study the role of eDNA and as a potential dispersal agent [18] [1]. |

| Dispersin B | A specific glycoside hydrolase that degrades the dPNAG exopolysaccharide. | Targeted dispersal of biofilms formed by pathogens like S. aureus and E. coli that rely on dPNAG [1]. |

| Quorum Sensing Inhibitors (QSIs) | Blocks cell-to-cell communication signals, preventing coordinated biofilm development. | Research into anti-biofilm strategies that do not exert selective pressure for classic resistance [20] [16]. |

| Fluorescent Antibiotics (e.g., Vancomycin-FL) | Allows for direct visualization of antibiotic penetration and localization within a biofilm. | Confocal microscopy studies to quantify diffusion barriers and binding within the EPS matrix [15]. |

Biofilms represent a significant mode of microbial existence, characterized by structured communities of bacteria encased in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) and adhering to biotic or abiotic surfaces [21]. In healthcare settings, these biofilms are a major source of persistent infections, contributing substantially to patient morbidity, mortality, and escalated healthcare costs [22] [23]. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) estimates that up to 80% of all human infections are biofilm-associated, with over 65% of hospital-acquired infections linked to biofilms on medical devices [24]. This technical resource provides scientists and researchers with targeted troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks to support research efforts aimed at understanding and disrupting biofilms within the context of persistent infections.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Epidemiological Data

1. What is the quantitative economic and clinical impact of biofilm-associated healthcare infections?

Biofilms exert a substantial economic and clinical burden globally. The annual global economic impact of biofilms is estimated to surpass $5 trillion [21]. In clinical terms, biofilm formation on medical devices is alarmingly common, with prevalence estimates ranging from 65% to 80% across various healthcare settings worldwide [23]. These infections lead to elevated patient morbidity and mortality, prolonged hospital stays, and increased treatment costs [22].

Table 1: Documented Resistance Patterns in Biofilm-Forming Pathogens from Clinical Surveillance

| Pathogen | Clinical Source | Key Resistance Findings | Susceptibility of Notable Antibiotics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa [22] | Respiratory, skin/soft tissue infections | 100% of isolates classified as MDR; 22.2% DTR; 5.4% PDR | Amikacin: 76.8%; Carbapenems: ~52%; Colistin: 43.8% |

| Staphylococcus aureus [22] | Hemodialysis patients | Both MRSA & MSSA formed strong biofilms; carried numerous virulence genes | Data not specified in source |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis [14] | Medical devices | 100% susceptible to vancomycin in planktonic state, but ~75% resistant when tested from a biofilm | Vancomycin (planktonic vs. biofilm): 100% vs. ~25% |

2. Why are biofilms inherently more resistant to antimicrobials and host immune responses?

Biofilms confer resistance through multiple, concurrent mechanisms [14]:

- Physical Barrier: The EPS matrix, composed of exopolysaccharides, proteins, and extracellular DNA (eDNA), restricts the penetration of antimicrobial agents and shields bacteria from immune cells [23] [25].

- Metabolic Heterogeneity: Gradients of nutrients and oxygen within the biofilm create microenvironments containing subpopulations of slow-growing or dormant "persister cells" that are highly tolerant to antibiotics [25] [14].

- Altered Microenvironment: Accumulated waste products and low oxygen zones within the biofilm can neutralize the activity of certain antibiotics, such as aminoglycosides [14].

- Enhanced Evasion: The biofilm matrix can shield bacterial pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), dampening the host's immune recognition and response [25].

3. What are the primary methodological challenges in visualizing and quantifying biofilms?

Researchers face several challenges in biofilm analysis:

- Structural Preservation: Sample preparation for techniques like conventional Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) often involves dehydration, which can cause collapse of the delicate EPS matrix and lead to artifactual shrinkage [4].

- Matrix Differentiation: Simple staining methods like Crystal Violet and Congo Red often fail to differentiate the bacterial cells from the surrounding EPS matrix [5].

- Cost and Complexity: Advanced techniques such as Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) and high-resolution SEM require expensive equipment and specialized expertise, making them inaccessible for some laboratories [4] [5].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Inconsistent Biofilm Formation in Static Models

- Potential Cause: Inoculum density variation; inadequate nutrient availability; surface properties of substrate.

- Solution: Standardize the inoculum preparation to a specific optical density (e.g., 0.5 McFarland standard) [5]. Use consistent, nutrient-rich broth and ensure the surface (e.g., polystyrene, glass) is sterile and physiochemically uniform. Validate formation with a reliable staining method.

Problem 2: Failure to Eradicate Mature Biofilms with Antimicrobial Agents

- Potential Cause: Standard antibiotics are ineffective against dormant persister cells and cannot penetrate the EPS matrix sufficiently.

- Solution: Consider combination therapies. Incorporate quorum sensing inhibitors (e.g., thymoquinone, Tanreqing preparation) to disrupt cell communication and biofilm integrity [22]. Utilize biofilm-disrupting agents such as enzymes (e.g., DNase to target eDNA) or nitric oxide (NO)-releasing compounds that can trigger biofilm dispersal [22] [24].

Problem 3: Inability to Distinguish Bacterial Cells from EPS Matrix via Light Microscopy

- Potential Cause: Conventional stains like Crystal Violet bind indiscriminately to biomass.

- Solution: Employ the dual-staining method using Congo Red and Maneval's stain [5]. This cost-effective technique differentiates cells (appearing magenta-red) from the surrounding polysaccharide matrix (appearing blue) under a light microscope, providing clear structural visualization.

Essential Experimental Protocols

This protocol is ideal for laboratories without access to advanced microscopy for distinguishing biofilm components.

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Maneval's Stain | Differentiates bacterial cells (magenta-red) and EPS matrix (blue). |

| Congo Red Dye (1%) | Initial stain that works in conjunction with Maneval's. |

| Formaldehyde (4%) | Fixes the biofilm structure, preserving its architecture. |

| Nutrient Broth | Medium for growing the biofilm. |

| Sterilized Glass Slide | Substrate for biofilm growth. |

Methodology:

- Biofilm Growth: Place a sterilized glass slide in a petri dish and submerge it in nutrient broth inoculated with a 1:100 dilution of a 0.5 McFarland standard bacterial suspension. Incubate undisturbed at 37°C for 3 days.

- Rinsing and Fixation: Gently rinse the slide by dipping it in distilled water for 5 seconds to remove non-adherent cells. Fix the biofilm by immersing the slide in 4% formaldehyde for 15-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Staining Procedure:

- Treat the fixed biofilm with 1% Congo red and allow it to air-dry completely.

- Apply Maneval's stain to the sample for 10 minutes.

- Remove excess stain and air-dry the slide.

- Visualization: Observe the biofilm under a light microscope using 100x oil immersion. Bacterial cells will appear magenta-red, surrounded by a blue polysaccharide layer.

This protocol is for high-resolution imaging of biofilm ultrastructure, though it requires careful handling to minimize artifacts.

Methodology:

- Primary Fixation: Rinse the biofilm-grown substrate gently and fix with 4% formaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15-30 minutes.

- Secondary Fixation and Cross-linking: Post-rinse with PBS, cross-link the sample with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M PBS for 2 hours at 4°C.

- Dehydration: Dehydrate the biofilm through a graded ethanol series (50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%), allowing 10 minutes at each concentration.

- Critical Point Drying and Coating: Subject the dehydrated sample to critical point drying. Sputter-coat the dried sample with a fine layer of gold or another conductive material.

- Imaging: Visualize the biofilm structure using a field-emission scanning electron microscope.

Analytical Frameworks: Pathways and Workflows

Biofilm Formation and Quorum Sensing Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of biofilm development and the central role of Quorum Sensing (QS) in its regulation, representing a primary target for disruption strategies.

Experimental Workflow for Biofilm Disruption Screening

This workflow outlines a systematic approach for screening and evaluating potential anti-biofilm compounds.

Bacterial biofilms are structured communities of microbial cells embedded in a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that adhere to both biotic and abiotic surfaces [26]. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has revealed that 60-80% of microbial infections are linked to biofilm formation, making them a principal concern in clinical settings [26]. Biofilms demonstrate dramatically enhanced resistance to antimicrobial compounds and host immune defenses compared to their free-floating (planktonic) counterparts, facilitating persistent infections that are difficult to eradicate [26] [27]. This resistance is multifactorial, arising from reduced antibiotic penetration due to the extracellular matrix, metabolic alterations in biofilm-resident bacteria, inactivation of antibiotics by matrix components, and increased exchange of bacterial resistance mechanisms [26].

Within the context of persistent infections research, understanding the distinct biofilm formation mechanisms of key pathogens is essential for developing effective disruption strategies. Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Haemophilus influenzae represent three clinically significant pathogens with diverse biofilm lifestyles that contribute substantially to the burden of device-related and chronic infections [26] [28] [29]. This technical resource provides troubleshooting guidance and methodological support for researchers investigating biofilm disruption strategies against these problematic pathogens.

Pathogen-Specific Biofilm Composition and Formation

Quantitative Comparison of Major Biofilm Components

Table 1: Key components of biofilm matrices for major pathogenic species

| Pathogen | Major Matrix Components | Primary Regulatory Systems | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | PIA/PNAG (polysaccharide), eDNA, proteins (FnBPs, Bap, PSMs) [27] | icaADBC operon (PIA synthesis), Agr system (quorum sensing) [27] | Medical device infections, chronic wounds, osteomyelitis [29] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Psl, Pel, alginate (polysaccharides), eDNA, proteins [30] [31] | Las, Rhl, Pqs, Iqs (quorum sensing systems) [31] | Cystic fibrosis lung infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia, catheter-associated UTIs [26] [30] |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Extracellular DNA, proteins, polysaccharides (less defined) [28] | Autoinducer-2 (quorum sensing) [28] | Otitis media, chronic rhinosinusitis, respiratory tract infections [28] |

Visualizing Biofilm Developmental Pathways

Figure 1: Generalized biofilm development cycle with pathogen-specific elements

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Experimental Design & Methodology

Q: What are the key considerations when selecting an in vitro biofilm model for antimicrobial efficacy testing?

A: The choice of biofilm model significantly impacts experimental outcomes. For preliminary, high-throughput screening, static models like microtiter plates are ideal. When evaluating antimicrobial treatments under relevant shear forces, dynamic models such as flow cells or CDC biofilm reactors are more appropriate [32]. Microcosm models that incorporate host components (e.g., hydroxyapatite for dental biofilms, human cell-coated surfaces) provide the most clinically relevant conditions but are more complex to establish [32]. Consider these key factors: your research question, required throughput, need for real-time observation, and available resources when selecting a model system.

Q: How can I optimize biofilm growth conditions for Haemophilus influenzae, particularly non-typable strains (NTHi)?

A: NTHi requires specific growth conditions for robust biofilm formation. Use brain heart infusion (BHI) broth supplemented with 2% Fildes enrichment and NAD (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) [28]. Incubate under microaerophilic conditions (5-10% CO~2~) at 35-37°C for 48-72 hours. For biofilm quantification, consider using the Calgary Biofilm Device which provides consistent shear force across all samples, promoting more uniform biofilm development [32]. Recent epidemiological studies indicate that ST103 and ST57 are predominant sequence types for NTHi, which may be valuable reference strains for method optimization [28].

Technical Challenges & Solutions

Q: What are the common reasons for inconsistent biofilm formation across experimental replicates?

A: Inconsistent biofilms typically result from these factors:

- Surface variability: Ensure identical surface materials and pretreatment across replicates

- Inoculum preparation: Standardize bacterial growth phase (mid-log phase recommended) and normalization methods

- Nutrient availability: Use fresh, properly prepared media with consistent lot numbers for critical components

- Environmental controls: Maintain stable temperature, humidity, and CO~2~ levels throughout incubation

- Shear force variation: In flow systems, calibrate pumps regularly to ensure consistent flow rates

For S. aureus, note that strain differences significantly impact biofilm formation capacity due to variable expression of adhesion factors and the icaADBC operon [27] [29]. Always include positive control strains with known biofilm-forming capabilities.

Q: How can I effectively disrupt mature biofilms for quantitative analysis without compromising bacterial viability?

A: Effective biofilm disruption requires matrix-specific approaches:

- Enzymatic treatment: Use combination cocktails including DNase I (targets eDNA), dispersin B (targets PNAG), or proteases (targets protein components) [33]

- Physical methods: Ultrasonication at optimized frequencies (20-40 kHz) with precise timing to minimize cell damage, or vortexing with glass beads for mechanical disruption

- Chemical agents: Dithiothreitol (DTT) can break disulfide bonds in matrix proteins, while chelating agents like EDTA disrupt cation-mediated matrix stability

Always validate disruption efficiency by comparing CFU counts before and after treatment and confirm complete disruption microscopically. Note that different pathogens and even strains may require optimized disruption protocols due to matrix composition differences [33].

Data Interpretation & Validation

Q: What controls are essential for proper interpretation of anti-biofilm experiments?

A: Implement a comprehensive control strategy:

- Viability controls: Planktonic cells of the same strain to distinguish biofilm-specific vs. general antimicrobial effects

- Matrix controls: Include matrix-deficient mutants (e.g., ica-negative S. aureus, psl/pel-negative P. aeruginosa) to confirm matrix-targeting mechanisms

- Treatment controls: Vehicle-only treatments to account for solvent effects

- Reference controls: Include approved antimicrobials with known anti-biofilm efficacy as benchmarks

- Neutralization controls: For time-kill assays, include appropriate neutralizers to prevent carry-over effect

Q: How can I distinguish between biofilm inhibition and biofilm eradication in experimental results?

A: These distinct outcomes require different experimental designs:

- Biofilm inhibition: Treat before or during biofilm formation, measure reduction in final biomass compared to untreated controls

- Biofilm eradication: Treat pre-established, mature biofilms (typically 24-72 hours old), measure reduction in existing biomass or viability

For P. aeruginosa, note that mucoid strains producing alginate demonstrate significantly enhanced eradication resistance compared to non-mucoid variants [30] [31]. Always report both the developmental stage at treatment initiation and the percentage reduction in viable counts or biomass to clearly communicate your findings.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential reagents and materials for biofilm research

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharide Intercellular Adhesion (PIA) Antibodies | Detection and quantification of S. aureus biofilm matrix [27] | Specific for deacetylated PNAG; critical for distinguishing PIA-dependent biofilms |

| Dispersin B | Enzymatic disruption of PNAG/PIA polysaccharide [33] | Effective against S. aureus and S. epidermidis biofilms; used at 10-100 µg/mL |

| DNase I | Degradation of extracellular DNA in biofilm matrix [30] [31] | Particularly effective against P. aeruginosa and H. influenzae biofilms; use concentration 10-100 U/mL |

| N-Acetylcysteine | Mucolytic agent that disrupts disulfide bonds in matrix [33] | Effective against alginate-rich P. aeruginosa biofilms; working concentration 0.5-5 mg/mL |

| Calgary Biofilm Device | High-throughput production of uniform biofilms [32] | Provides reproducible biofilm samples for antimicrobial susceptibility testing |

| Crystal Violet | Total biofilm biomass staining and quantification [32] | Standard static biofilm assessment; measure absorbance at 570-595 nm after elution |

| Resazurin Reduction Assay | Metabolic activity measurement in biofilms [32] | Non-destructive alternative to CFU counting; fluorescence measurement (560/590 nm) |

| Syto 9/Propidium Iodide | Live/dead visualization of biofilm architecture [32] | Confocal microscopy analysis of biofilm viability and structure |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Microtiter Plate Biofilm Assay

This fundamental protocol adapts to all three pathogens with modifications:

- Inoculum preparation: Grow bacteria to mid-log phase (OD~600~ = 0.5-0.8) and dilute in appropriate broth to approximately 10^6^ CFU/mL

- Biofilm formation: Aliquot 200 µL/well into 96-well plates, incubate statically:

- Biofilm quantification:

- Carefully remove planktonic cells by rinsing 3× with PBS

- Fix with 200 µL 99% methanol for 15 minutes

- Air dry, then stain with 200 µL 0.1% crystal violet for 15 minutes

- Rinse thoroughly with water to remove unbound stain

- Elute bound stain with 200 µL 33% acetic acid

- Measure absorbance at 570-595 nm

Troubleshooting note: For H. influenzae, supplement media with NAD and hematin for optimal growth and biofilm formation [28].

Biofilm Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Standardized methods for evaluating anti-biofilm compounds:

- Biofilm establishment: Grow biofilms as described in section 5.1

- Treatment application: Replace medium with fresh medium containing test compounds at desired concentrations

- Incubation: Incubate for appropriate time based on compound mechanism (typically 24 hours)

- Viability assessment:

- Option 1: Disrupt biofilms by sonication or scraping, then perform serial dilution and plating for CFU enumeration

- Option 2: Use metabolic assays (XTT, resazurin) for indirect viability measurement

- Biomass assessment: Perform crystal violet staining as in section 5.1 to determine biomass reduction

Key consideration: For P. aeruginosa, note that aminoglycoside resistance is enhanced by Pel polysaccharide, while colistin resistance involves multiple matrix components [30] [31]. Always include both planktonic and biofilm-treated samples to determine biofilm-specific resistance ratios.

Advanced Methodologies

Flow Cell Biofilm Analysis for Real-Time Observation

Flow cells provide unparalleled analysis of biofilm architecture and development dynamics:

Figure 2: Flow cell biofilm analysis workflow with pathogen-specific modifications

Molecular Analysis of Biofilm Regulation

Key pathways and their investigation:

Quorum Sensing Inhibition Studies

- P. aeruginosa: Target LasR/LasI and RhlR/RhlI systems with furanone compounds or natural inhibitors [31]

- S. aureus: Target Agr system with RNAIII-inhibiting peptide (RIP) or ambuic acid analogs [27]

- H. influenzae: Investigate autoinducer-2 (AI-2) interference strategies [28]

Gene Expression Analysis in Biofilms

- Extract RNA from mechanically disrupted biofilms

- Validate reference genes for biofilm conditions (gyrA, rpoB often more stable than 16S rRNA)

- Key regulatory targets:

This technical support resource provides foundational methodologies and troubleshooting guidance for researchers developing biofilm disruption strategies against these clinically significant pathogens. As biofilm research evolves, continue to validate these approaches against emerging models and clinical isolates to ensure translational relevance.

Emerging Anti-Biofilm Technologies: From Enzymatic Disruption to Nanotechnology

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My glycoside hydrolase treatment failed to disperse a mature S. aureus biofilm in an in vivo wound model, even though it worked in vitro. What could be the reason?

A: This is a common issue related to the model system and potential changes in the biofilm's extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) composition. Biofilms grown in vivo often have a different EPS structure compared to those grown in simple in vitro systems [34]. S. aureus produces poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG) as a key exopolysaccharide [35]. If your chosen glycoside hydrolase (e.g., cellulase or α-amylase) does not target the specific linkages in PNAG, it will have limited efficacy. It is crucial to select an enzyme, such as dispersin B, that specifically hydrolyzes β-1,6 linkages in PNAG [36] [35]. Furthermore, the in vivo environment includes host components that can integrate into the biofilm, potentially altering its architecture and accessibility to enzymes [34].

Q2: I am observing a strong inflammatory response in my animal model following successful enzymatic biofilm dispersal. Is this expected, and how can it be managed?

A: Yes, this is an expected consequence of effective biofilm disruption. Biofilms act as a physical shield, sequestering pathogens from the host immune system [36] [35]. Dispersing the biofilm releases a sudden, high load of planktonic bacteria and EPS components, triggering a significant localized immune response [37]. To manage this in an experimental setting, consider the following:

- Antimicrobial Synergy: Always pair enzymatic dispersal agents with an appropriate antibiotic. The goal of dispersal is to convert tolerant sessile cells into susceptible planktonic cells, which can then be killed by the antimicrobial, thereby reducing the antigenic load [38] [35].

- Monitor Host Response: Include biomarkers of inflammation (e.g., cytokine levels, neutrophil infiltration) as key metrics in your study to quantify this effect [35].

Q3: How do I determine the optimal concentration and treatment duration for a novel protease against a Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm?

A: A systematic, empirical approach is required, as efficacy is strain and model-dependent.

- Start with In Vitro Screening: Use a standard assay like a crystal violet biomass assay or a dispersal assay to test a range of enzyme concentrations (e.g., 0.0025% to 5%) and treatment times (e.g., 2 minutes to 2 hours) on pre-formed biofilms [38].

- Validate with Viability Counts: Follow up with colony forming unit (CFU) counts of both dispersed and remaining biofilm-associated cells to confirm that dispersal is increasing antibiotic efficacy without exhibiting bactericidal activity itself [38].

- Progress to Complex Models: Confirm the optimal dose in a more clinically relevant model, such as a wound microcosm or an in vivo infection model, as efficacy can differ significantly from in vitro results [34].

Q4: Can enzymatic agents effectively disrupt polymicrobial biofilms, and are there any special considerations?

A: Yes, enzymes can be effective against polymicrobial biofilms, which are common in clinical infections like chronic wounds [38]. However, the EPS composition might be more complex. A combination of enzymes targeting different components (e.g., a glycoside hydrolase with a DNase or protease) may be more effective than a single enzyme, as it can target the diverse structural elements contributed by different species [35]. Research shows that a 1:1 mixture of α-amylase and cellulase was effective at dispersing a dual-species S. aureus and P. aeruginosa biofilm [38].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Well-Plate Biofilm Dispersal and Assessment

This protocol is adapted from methods used to evaluate glycoside hydrolase efficacy against mono- and dual-species biofilms [38] [34].

Objective: To quantify the dispersal efficacy of an enzymatic agent on a pre-formed biofilm in a 24-well plate format.

Materials:

- Bacterial strains (e.g., P. aeruginosa PAO1, S. aureus SA31)

- Glycoside hydrolase solution (e.g., α-amylase, cellulase) in 1x PBS

- 24-well non-tissue culture-treated plates

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Crystal violet stain (0.1%) or materials for CFU plating

Method:

- Inoculation: Inoculate wells with 10^5 CFU of bacteria in 800 μL of appropriate growth medium. For polymicrobial biofilms, include 20% adult bovine serum to prevent one species from outcompeting the other [34].

- Biofilm Growth: Incubate plates for 48 hours at 37°C with gentle shaking (80 rpm).

- Rinsing: Gently remove the supernatant and rinse each well with 1 mL of PBS to remove non-adherent planktonic cells.

- Enzyme Treatment: Add 1 mL of the enzyme solution (or PBS vehicle control) to each well. Incubate for a predetermined time (e.g., 30 min to 2 h) at 37°C with shaking [38].

- Analysis:

- Biomass Assessment (Crystal Violet): After treatment, remove supernatant, stain biofilm with crystal violet, and elute for spectrophotometric quantification [38].

- Dispersal Assessment (CFU Count): Collect the treatment supernatant ("dispersed fraction"). Add 1 mL PBS to the well and sonicate or homogenize to resuspend the remaining biofilm ("biofilm fraction"). Serially dilute both fractions and spot plate to determine CFU counts. Calculate percent dispersal as: (Dispersed CFU / Total CFU) * 100 [34].

Troubleshooting Tip: If dispersal is low, confirm enzyme activity and test a range of concentrations. Heat-inactivated enzyme should be used as a negative control to rule out non-specific effects [38].

Protocol 2: In Vivo Murine Chronic Wound Biofilm Model for Enzyme Efficacy

This protocol outlines a method for assessing enzymatic dispersal in a clinically relevant animal model [38] [34].

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of a dispersal enzyme on biofilms established within a murine wound.

Materials:

- Mice (e.g., SKH1-Elite immunocompromised mice for chronic wound model)

- Bacterial inoculum

- Enzyme solution in 1x PBS

- Surgical tools for wound creation and biofilm extraction

Method:

- Wound Creation and Infection: Create a full-thickness wound on the dorsal surface of an anesthetized mouse. Infect the wound with the bacterial strain(s) of interest and cover with a semi-occlusive dressing [34].

- Biofilm Establishment: Allow the biofilm to develop for 3-7 days.

- Biofilm Extraction and Ex Vivo Treatment: Euthanize the animal and surgically extract the biofilm-containing wound bed tissue.

- Treatment: Weigh the extracted tissue and treat it ex vivo with the enzyme solution or a control for 1 hour at 37°C with shaking [38].

- Analysis:

- Biomass Degradation: Weigh the tissue after treatment and calculate the percent reduction in weight compared to the control [38].

- Cell Dispersal: After treatment, serially dilute the treatment solution ("dispersed fraction") and homogenize the remaining tissue ("biofilm fraction") to determine viable CFU counts and calculate percent dispersal [38].

Troubleshooting Tip: The in vivo biofilm microenvironment is complex. Include a group that receives enzyme followed by a systemic antibiotic to demonstrate the full therapeutic potential of the dispersal strategy [38].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Enzymatic Agents for Biofilm Dispersal and Their Applications

| Reagent | Target | Function in Biofilm Dispersal | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Amylase [38] [34] | α-1,4 glycosidic linkages | Hydrolyzes polysaccharides with α-1,4 bonds (e.g., starch, P. aeruginosa Pel polysaccharide) [34]. | Dispersal of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus mono- and polymicrobial biofilms [38]. |

| Cellulase [38] [34] | β-1,4 glycosidic linkages | Hydrolyzes polysaccharides with β-1,4 bonds (e.g., cellulose, P. aeruginosa Psl and Alginate) [38] [34]. | Dispersal of P. aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia biofilms; effective in polymicrobial wound biofilms [38]. |

| Dispersin B [38] [35] | β-1,6 glycosidic linkages in PNAG | Specifically hydrolyzes poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG), a key biofilm polysaccharide in many bacteria [35]. | Prevention and disruption of biofilms from Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and other PNAG-producing pathogens [38]. |

| Proteases (e.g., Trypsin, Proteinase K) [35] | Proteinaceous adhesins and matrix proteins | Degrades protein components within the EPS, disrupting structural integrity and cellular adhesion [35]. | Dispersal of biofilms where proteins are a major matrix component; often used in combination with other enzymes [35]. |

| Deoxyribonucleases (DNases) [35] | Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | Hydrolyzes the eDNA backbone, a crucial structural and adhesive component in many bacterial biofilms [35]. | Dispersal of biofilms from species like P. aeruginosa and S. aureus that rely on eDNA for matrix stability [35]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Efficacy of Glycoside Hydrolases in Different Biofilm Models

| Biofilm Model | Species | Enzyme | Concentration | Key Quantitative Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Well-Plate | S. aureus & P. aeruginosa (coculture) | α-Amylase | 0.25% | Significant reduction in biofilm biomass (crystal violet assay) [38]. | |

| In Vitro Well-Plate | S. aureus & P. aeruginosa (coculture) | Cellulase | 0.25% | Significant reduction in biofilm biomass (crystal violet assay) [38]. | |

| In Vitro Well-Plate | S. aureus & P. aeruginosa (coculture) | α-Amylase & Cellulase (1:1) | 5% | Significant increase in total cell dispersal compared to vehicle control [38]. | |

| Ex Vivo Murine Wound | S. aureus & P. aeruginosa (coculture) | α-Amylase | 5% | Degraded biofilm biomass and increased bacterial cell dispersal from infected wound beds [38]. | |

| Ex Vivo Murine Wound | S. aureus & P. aeruginosa (coculture) | Cellulase | 5% | Degraded biofilm biomass and increased bacterial cell dispersal from infected wound beds [38]. | |

| In Vitro Microcosm | S. aureus (monospecies) | Cellulase | 5% | Striking loss of dispersal efficacy compared to in vitro well-plate model [34]. |

Experimental Workflows and Pathways

Biofilm Dispersal Experimental Workflow

Enzyme Targeting of Biofilm EPS

Quorum Sensing Inhibitors and Signal Interference Strategies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary advantage of using Quorum Sensing Inhibitors (QSIs) over traditional antibiotics? QSIs offer a novel anti-virulence strategy by disrupting bacterial communication without exerting a lethal selection pressure. This approach can attenuate pathogenicity and biofilm formation, thereby reducing the likelihood of resistance development compared to conventional antibiotics that kill or inhibit growth and promote resistance selection [39] [40].

2. Why are my QSI assays against Pseudomonas aeruginosa showing inconsistent results? P. aeruginosa possesses multiple, redundant QS systems (Las, Rhl, PQS, IQS). Inhibiting only one pathway may be insufficient due to compensatory crosstalk. For consistent results, consider using a combination of inhibitors targeting different systems or validate efficacy using reporter gene assays for each specific pathway [39].

3. What are common reasons for the lack of antibiofilm effect in a QSI compound that shows promise in initial screening? This discrepancy can occur due to several factors:

- Poor Biofilm Penetration: The compound may not effectively diffuse through the dense extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix [6] [15].

- Wrong Timing: QSIs are most effective when applied during early-stage biofilm formation. If added to a mature biofilm, their efficacy is significantly reduced [41].

- Compound Degradation: The QSI might be degraded by bacterial enzymes or host factors in the experimental system [40].

4. Which bacterial strains are recommended for initial validation of broad-spectrum QSI activity? For an initial broad-spectrum screening, use reporter strains responsive to the universal signal Autoinducer-2 (AI-2). Vibrio harveyi bioluminescence assays or engineered E. coli AI-2 reporter strains are standard models. For Gram-negative specific AHL inhibition, Chromobacterium violaceum CV026 is excellent for visual screening based on violacein pigment inhibition [40].

5. How can I differentiate between QSI activity and general antibacterial toxicity in my assays? It is crucial to include control experiments that measure bacterial growth (e.g., OD600). A true QSI will inhibit QS-regulated phenotypes (e.g., virulence factor production, biofilm formation) without significantly affecting microbial growth rates. If growth is inhibited, the observed effect may be due to bacteriostatic or bactericidal activity [39] [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Cytotoxicity of QSI Compounds in Mammalian Cell Lines

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inherent Toxicity of Lead Compound. The chemical structure of the QSI may have non-specific cytotoxic effects.

- Solution: Perform structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies to identify and modify the toxic pharmacophore. Explore synthetic derivatives or analogs with lower cytotoxicity [40].

- Cause 2: Solvent Toxicity. The solvent used (e.g., DMSO) may be at a cytotoxic concentration.

- Solution: Ensure the final concentration of the solvent (e.g., DMSO <0.1%) is non-toxic to the cell line in control experiments.

- Cause 3: Low Therapeutic Index. The effective QSI concentration is close to the cytotoxic concentration.

Problem: QSI Loses Efficacy in Complex In Vivo Models

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Serum Protein Binding. The QSI may bind to serum proteins, reducing its free, active concentration.

- Solution: Modify the compound to reduce protein binding or use delivery vehicles that protect the payload until it reaches the infection site [40].

- Cause 2: Rapid Clearance or Metabolism. The compound may be quickly metabolized or cleared from the host system.

- Solution: Investigate the pharmacokinetic profile and chemically modify the compound to improve its stability and half-life [40].

- Cause 3: Inadequate Biofilm Penetration.

Problem: Rapid Development of Bacterial Resistance to QSI Monotherapy

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Evolutionary Adaptation. While QSIs impose less selective pressure than antibiotics, bacteria can still develop resistance through mutations in QS receptor genes or upregulation of efflux pumps [40].

Quantitative Data on Common QSIs and Their Efficacy

The following table summarizes key quantitative data for selected natural QSIs, which is essential for dose selection and experimental design.

Table 1: Efficacy Parameters of Selected Natural Quorum Sensing Inhibitors

| QSI Compound | Source | Target Bacteria / QS System | Key Effect | MIC/MBIC/IC₅₀ Value | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin | Plant (Turmeric) | P. aeruginosa (Las/Rhl) | Inhibits AHL synthesis, reduces biofilm | MBIC₅₀: ~50 µM | [40] [44] |

| Patulin | Fungal Metabolite | P. aeruginosa (LasB) | Inhibits LasR, reduces virulence factor (elastase) | IC₅₀: 17.8 µM | [40] |

| Caffeine | Plant | P. aeruginosa | Reduces pyocyanin, elastase; inhibits biofilm | ~2-4 mg/mL for significant inhibition | [6] |

| Salicylic Acid | Plant (Willow Bark) | P. aeruginosa & E. coli | Reduces AHL production, inhibits swarming | 0.5 - 1 mg/mL for biofilm inhibition | [6] |

| AiiA Lactonase | Enzyme (Bacillus sp.) | Broad-spectrum (AHL degrader) | Degrades AHL signals, inhibits biofilm formation | Effective in nanomolar ranges | [40] [44] |

| RNAIII-Inhibiting Peptide (RIP) | Synthetic Peptide | S. aureus (Agr) | Blocks Agr QS, reduces biofilm & virulence | 10 - 50 µM for inhibition | [44] |

MIC: Minimum Inhibitory Concentration; MBIC: Minimum Biofilm Inhibitory Concentration; IC₅₀: Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration; AHL: Acyl-Homoserine Lactone

Experimental Protocols for Key QSI Assays

Protocol 1: Qualitative Screening for Anti-Virulence Activity usingChromobacterium violaceumCV026

Principle: The CV026 mutant is deficient in AHL production but produces the purple pigment violacein in response to exogenous AHLs. QSIs that antagonize the receptor or degrade AHLs will inhibit violacein production.

Materials:

- C. violaceum CV026 reporter strain

- AHL signal (e.g., C6-HSL)

- Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates

- Test compounds and controls (e.g., solvent control, known QSI)

Method:

- Prepare a soft agar overlay: Mix an overnight culture of CV026 with molten LB agar (0.75% agar) and the inducing AHL (e.g., 10 µM C6-HSL). Pour over a base LB agar plate.

- Apply test compounds: Using a sterile tip, spot 10-20 µL of the test compound solution onto the solidified overlay. Alternatively, use paper discs impregnated with the compound.

- Incubate: Incubate the plates at 28-30°C for 24-48 hours.

- Interpretation: Observe for a zone of colorless, non-pigmented bacterial growth around the spot/disc, indicating successful QS inhibition. No zone of growth inhibition should be present, confirming the effect is anti-virulence and not antibacterial [40].

Protocol 2: Quantitative Assessment of Biofilm Inhibition using Microtiter Plate Assay

Principle: This high-throughput crystal violet (CV) staining method quantifies total biofilm biomass. It is used to determine the Minimum Biofilm Inhibitory Concentration (MBIC) of QSIs.

Materials:

- 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene microtiter plates

- Test bacterial culture (e.g., P. aeruginosa PAO1, S. aureus)

- Crystal violet solution (0.1% w/v)

- Acetic acid (30% v/v) or ethanol (95-100%)

- Microplate reader

Method:

- Inoculation: Grow bacteria to mid-log phase and dilute in fresh medium. Add 100 µL per well containing serially diluted QSIs. Include a growth control (bacteria, no QSI) and a sterility control (medium only).

- Incubation: Incubate statically at 37°C for 24-48 hours to allow biofilm formation.

- Staining:

- Carefully remove the planktonic cells by inverting and shaking the plate.

- Wash the adhered biofilms gently with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice.

- Fix the biofilms by air-drying for 30-45 minutes.

- Add 125 µL of 0.1% crystal violet to each well and stain for 15-20 minutes.

- Destaining and Quantification:

- Wash the stained plates thoroughly under running tap water to remove unbound dye.

- Add 125 µL of 30% acetic acid (or 95% ethanol) to solubilize the crystal violet bound to the biofilm.

- Incubate for 10-15 minutes with shaking.

- Transfer 100 µL of the solubilized dye to a new microtiter plate (if using acetic acid with the original plate).

- Measure the absorbance at 570-600 nm.

- Analysis: The MBIC is defined as the lowest concentration of QSI that results in a ≥50% reduction (MBIC₅₀) or ≥90% reduction (MBIC₉₀) in absorbance compared to the untreated growth control [6] [42].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for QSI and Biofilm Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application in QSI Research |

|---|---|

| Reporter Strains (e.g., C. violaceum CV026, V. harveyi BB170, P. aeruginosa lasB-gfp*) | Essential for visualizing and quantifying QS inhibition. Used in initial screening and mechanism elucidation [40]. |

| Acyl-Homoserine Lactones (AHLs) | Native QS signaling molecules in Gram-negative bacteria. Used as positive controls and to induce QS in reporter assays [39]. |

| Autoinducing Peptides (AIPs) | Native QS signaling molecules in Gram-positive bacteria. Used for studying and inhibiting Agr-like systems [39] [44]. |

| Crystal Violet | A basic dye used in microtiter plate assays to stain and quantify total biofilm biomass [6] [42]. |

| DNase I | An enzyme that degrades extracellular DNA (eDNA) in the biofilm matrix. Used in combination studies to enhance QSI penetration [6] [15]. |

| Dispersin B | A glycoside hydrolase enzyme that degrades poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG), a key polysaccharide in many biofilms. Used as a biofilm-dispersing agent [15]. |

| Microtiter Plates (Polystyrene, U-bottom/F-bottom) | The standard platform for high-throughput, quantitative biofilm cultivation and antibiofilm susceptibility testing [42]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows