Confronting the Crisis: Decoding Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms in Gram-Negative Bacteria

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sophisticated mechanisms underpinning antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Gram-negative bacteria, a critical global health threat.

Confronting the Crisis: Decoding Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms in Gram-Negative Bacteria

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sophisticated mechanisms underpinning antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Gram-negative bacteria, a critical global health threat. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational science, current methodological approaches for detection and treatment, strategies to overcome resistance, and comparative validation of novel therapeutics. Covering the unique tri-layered cell envelope, enzymatic inactivation, efflux pumps, and target modifications, the review also explores the dwindling antibiotic pipeline and innovative solutions like beta-lactamase inhibitors, novel antibiotic classes, and alternative therapies. The content is framed within the context of the WHO's Bacterial Priority Pathogen List and the latest 2024-2025 surveillance data, offering a roadmap for future research and clinical intervention.

The Gram-Negative Fortress: Structural and Genetic Foundations of Resistance

The escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most urgent global healthcare and economic threats, with Gram-negative bacterial pathogens at its epicenter [1]. The remarkable resilience of these organisms stems primarily from their complex cell envelope, a formidable macromolecular structure that effectively excludes diverse classes of therapeutic agents [1] [2]. In 2017, the World Health Organization classified several Gram-negative species as priority pathogens, emphasizing the critical need for novel therapeutic strategies to overcome this protective barrier [1]. The Gram-negative cell envelope is not merely a passive shield but a dynamically interactive compartment that employs multiple, overlapping resistance mechanisms. These include enzymatic antibiotic inactivation, restricted uptake through outer membrane remodelling, efflux pump-mediated antibiotic extrusion, and target site modification [1]. This whitepaper deconstructs the structural and functional complexity of the Gram-negative cell envelope, frames its role in antimicrobial resistance, and provides researchers with advanced methodological approaches for investigating this formidable barrier and developing countermeasures to overcome it.

Structural and Functional Organization of the Gram-Negative Cell Envelope

The Gram-negative cell envelope is a remarkable, multi-layered structure strong enough to withstand approximately 3 atmospheres of turgor pressure, tough enough to endure extreme temperatures and pH, and elastic enough to expand several times its normal surface area [3]. This composite architecture comprises three distinct yet interconnected components: the outer membrane (OM), the peptidoglycan cell wall, and the inner membrane (IM), which together create a sophisticated permeability barrier [1] [2].

The Asymmetric Outer Membrane

The outer membrane represents the defining feature of Gram-negative bacteria and the primary interface with the host environment [1] [2]. Its most distinctive characteristic is its asymmetric lipid distribution. The inner leaflet consists of phospholipids, while the outer leaflet is composed primarily of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [2]. This asymmetry is fundamental to the membrane's barrier function. LPS is a glycolipid molecule consisting of three domains: lipid A (the hydrophobic anchor), a core oligosaccharide, and the O-antigen polysaccharide chain [2]. The LPS molecules pack tightly together, especially when stabilized by divalent cations like Mg²⁺ that neutralize the negative charges of phosphate groups, creating a highly ordered, non-fluid continuum that is exceptionally impermeable to hydrophobic molecules [2].

The outer membrane is studded with proteins that can be broadly categorized into lipoproteins and β-barrel outer membrane proteins (OMPs) [1] [2]. Lipoproteins are anchored to the inner leaflet via their lipid moieties and play essential roles in cell virulence, peptidoglycan remodelling, cell division, and OM biogenesis [1]. The β-barrel OMPs are transmembrane proteins whose β-sheets wrap into cylindrical pores. They include:

- Porins (e.g., OmpF, OmpC): Form water-filled channels allowing passive diffusion of small, hydrophilic molecules (typically <600 Da) [2] [4].

- Substrate-specific channels (e.g., LamB for maltodextrins): Facilitate transport of specific nutrients [2].

- Gated channels (e.g., for vitamin B12 transport): Mediate high-affinity uptake of larger ligands [2].

Table 1: Major Outer Membrane Components and Their Functions in Gram-Negative Bacteria

| Component | Chemical Structure | Primary Function | Role in Barrier Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Glycolipid with Lipid A core, polysaccharide chains | Structural integrity; endotoxic activity | Creates highly impermeable outer leaflet to hydrophobic compounds |

| General Porins (OmpF, OmpC) | Trimeric β-barrel proteins | Passive diffusion of small hydrophilic molecules (<600 Da) | Governs influx of nutrients and antibiotics; mutation causes resistance |

| Specific Porins (LamB, PhoE) | Trimeric β-barrel with substrate specificity | Selective uptake of specific molecules (maltodextrins, phosphate) | Nutrient acquisition; can serve as entry points for antimicrobial analogs |

| Braun's Lipoprotein | Lipoprotein covalently linked to peptidoglycan | Anchors outer membrane to peptidoglycan layer | Stabilizes envelope structure; critical for mechanical integrity |

The Periplasm and Peptidoglycan Layer

Sandwiched between the outer and inner membranes lies the periplasm, an aqueous compartment that constitutes an integral part of the Gram-negative cell envelope [3] [5]. This concentrated gel-like matrix contains binding proteins for nutrients, degradative and detoxifying enzymes, and plays a crucial role in bacterial nutrition and stress response [3] [5]. The periplasm can also act as a reservoir for surface-associated components like pilins, S-layer proteins, and virulence factors [3].

Within the periplasmic space resides the peptidoglycan (or murein) layer, a thin, mesh-like scaffold that surrounds the bacterial inner membrane [1] [2]. In Gram-negative bacteria, this layer is substantially thinner than in Gram-positive organisms but remains essential for withstanding osmotic pressure and maintaining cell shape [1]. The peptidoglycan is composed of linear glycan strands of alternating N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc) residues, cross-linked by short peptides to form a covalently closed, net-like structure called the sacculus [1].

The Inner Membrane

The inner membrane is a symmetric phospholipid bilayer that serves as the ultimate permeability barrier between the cytoplasm and the external environment [1]. It contains numerous proteins responsible for critical cellular functions, including lipid and protein biosynthesis, secretion, DNA anchoring, and chromosome separation [1] [6]. Unlike the outer membrane, the inner membrane lacks LPS and is a metabolically active structure involved in energy generation, solute transport, and macromolecular synthesis [1].

Resistance Mechanisms: How the Envelope Thwarts Antibiotic Therapy

The Gram-negative cell envelope contributes to antibiotic resistance through four primary mechanisms that can operate independently or synergistically to create clinically significant resistance phenotypes [1].

Restricted Antibiotic Permeation

The outer membrane serves as a formidable physical barrier that significantly limits antibiotic penetration [7] [4]. The LPS-rich outer leaflet is exceptionally effective at excluding hydrophobic antibiotics, while the size-restrictive porin channels constrain the entry of hydrophilic molecules [2] [4]. Systematic analyses in E. coli have demonstrated that different porins play distinct roles in antibiotic resistance. For instance, OmpF serves as the main penetration route for many antibiotics including β-lactams, while OmpA is primarily associated with maintaining membrane integrity [4]. OmpC appears to contribute to both functions [4]. Porin deficiencies, whether through mutational inactivation or downregulation of expression, are common resistance mechanisms in clinical isolates [7] [4].

Efflux Pump-Mediated Antibiotic Extrusion

Gram-negative bacteria express a plethora of efflux pumps that are capable of transporting structurally diverse molecules, including antibiotics, out of the bacterial cell [8] [7]. These tripartite efflux systems span both the inner and outer membranes, efficiently recognizing and extruding drugs from the periplasm before they reach their intracellular targets [7]. In Enterobacteriaceae, all parallel efflux pathways based on tripartite pumps converge at the outer membrane protein TolC, making it a central conduit for multidrug efflux [7]. Overexpression of these efflux systems can cause clinically relevant levels of antibiotic resistance [8]. Recent large-scale chemical analyses have revealed that alongside collective physicochemical properties, the presence or absence of specific chemical groups in compounds substantially influences their recognition by TolC-dependent efflux systems [7].

Table 2: Major Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms Associated with the Gram-Negative Cell Envelope

| Resistance Mechanism | Molecular Basis | Antibiotic Classes Affected | Research Assessment Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted Permeation | Porin loss/modification; LPS barrier | β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, chloramphenicol | MIC profiling; Porin expression analysis; Liposome swelling assays |

| Efflux Pump Expression | Overexpression of tripartite efflux systems (e.g., AcrAB-TolC) | Multiple classes including tetracyclines, macrolides, β-lactams | Ethidium bromide accumulation assays; RT-qPCR of efflux components; Checkerboard assays with efflux inhibitors |

| Enzyme-Mediated Inactivation | Production of β-lactamases, aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes in periplasm | β-lactams, aminoglycosides | Nitrocefin hydrolysis assays; Enzyme kinetics; Mass spectrometry of modified antibiotics |

| Target Modification | Alteration of PBPs, DNA gyrase, other targets accessed through envelope | β-lactams, fluoroquinolones | Target gene sequencing; Binding affinity measurements; Radioligand displacement assays |

Enzyme-Mediated Inactivation and Target Modification

The periplasmic space houses numerous antibiotic-inactivating enzymes, most notably β-lactamases, which hydrolyze β-lactam antibiotics before they can reach their penicillin-binding protein (PBP) targets [1] [5]. Additionally, bacteria can alter antibiotic target sites through mutations or post-translational modifications, further reducing antibiotic efficacy [1]. These target modifications are particularly effective when combined with reduced permeability and enhanced efflux, creating a multi-layered defense system that is extremely difficult to overcome with conventional antibiotics.

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Envelope-Mediated Resistance

Genetic Manipulation of Envelope Components

The construction of defined mutants provides a powerful approach for systematically analyzing the contribution of individual envelope components to antibiotic resistance. For example, researchers can create:

- Porin deletion mutants: Generate single, double, and triple porin mutants (e.g., ΔompA, ΔompC, ΔompF) to assess their individual and combined contributions to antibiotic susceptibility [4].

- Efflux-deficient strains: Create tolC mutants to disable the major efflux conduit in Enterobacteriaceae, allowing identification of efflux pump substrates [7].

- Membrane-permeable mutants: Utilize lpxC mutants with reduced LPS content to create hyperpermeable outer membranes for studying permeation limitations [7].

Protocol: Construction of Porin Deletion Mutants Using λ Red Recombinase

- Amplify a kanamycin-resistance gene from plasmid pKD13 using primers containing 50-nucleotide extensions homologous to the target porin gene.

- Electroporate the purified PCR product into E. coli MG1655 cells harboring the pKD46 plasmid (expressing λ Red recombinase).

- Select mutants on LB agar plates containing kanamycin (50 μg/mL) at 37°C.

- Eliminate the antibiotic resistance cassette by transforming with pCP20 plasmid expressing FLP recombinase.

- Verify gene deletion by colony PCR and DNA sequencing [4].

Phenotypic Characterization of Envelope Mutants

Comprehensive profiling of envelope mutants reveals the functional contribution of specific components to antibiotic resistance and membrane integrity.

Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

- Determine Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values using the agar dilution method according to CLSI guidelines.

- Spot 10 μL of bacterial suspension (10⁷ cells/mL) onto Müller-Hinton agar plates containing two-fold serial dilutions of antibiotics.

- Incubate at 37°C for 20 hours; define MIC as the lowest antibiotic concentration preventing visible growth [4].

Membrane Integrity Assays

- Spot serial dilutions of stationary-phase cells onto LB plates containing membrane stressors (2% SDS, 6% ethanol, 750 mM NaCl).

- Assess membrane permeability using fluorescent dyes (propidium iodide, SYTOX green) that are excluded by intact membranes but penetrate compromised envelopes.

- Visualize stained cells using fluorescence microscopy to quantify membrane damage [4].

Efflux Pump Activity Assessment

- Measure intracellular accumulation of efflux pump substrates (e.g., ethidium bromide) in wild-type versus efflux-deficient strains using fluorometry.

- Compare compound activity in wild-type versus tolC strains to classify compounds as efflux substrates or efflux evaders [7].

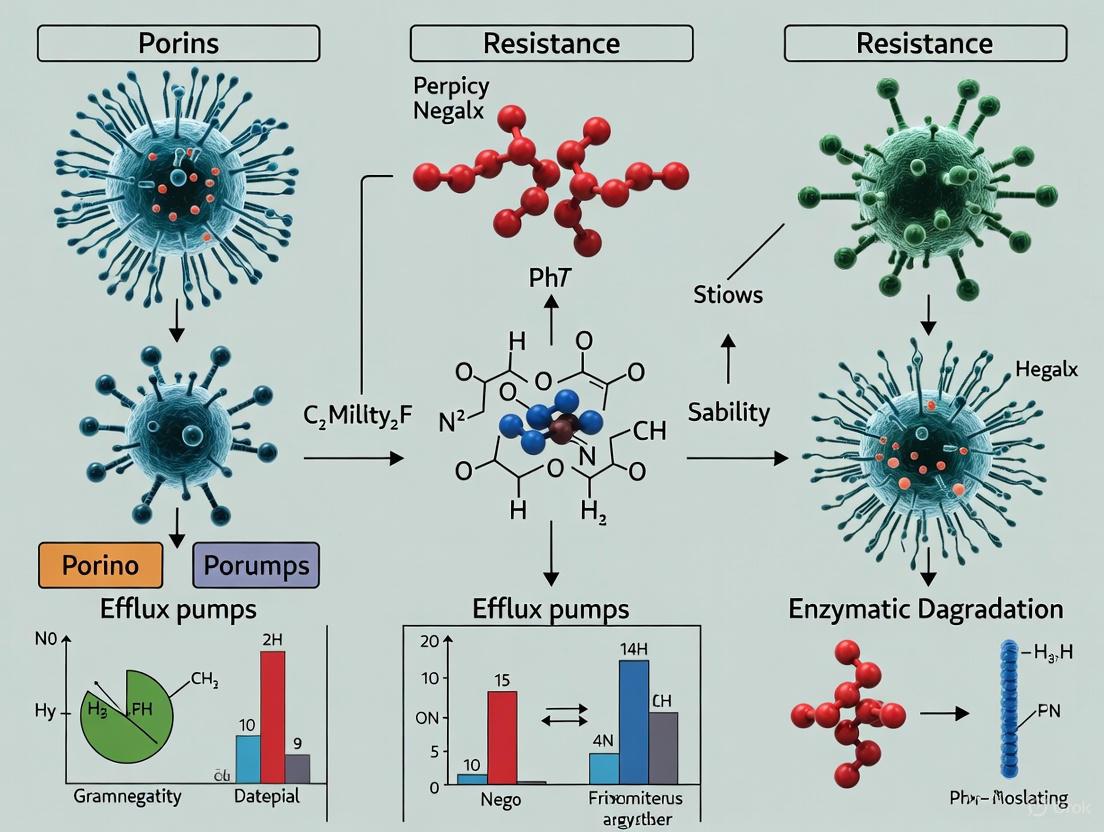

The following diagram illustrates the primary antibiotic resistance mechanisms employed by the Gram-negative cell envelope and their complex interrelationships:

Diagram 1: Multilayered antibiotic resistance mechanisms in Gram-negative bacteria. The diagram illustrates how antibiotics (yellow) must navigate the outer membrane (green), may be inactivated in the periplasm (red), or recognized by efflux pumps (blue) that extrude them from the cell.

Computational and High-Throughput Approaches

Modern resistance research employs large-scale screening and computational methods to identify chemical features associated with envelope penetration and efflux avoidance.

Large-Scale Compound Classification

- Source experimental growth inhibition data from public databases (e.g., CO-ADD) for wild-type, tolC, and lpxC E. coli strains.

- Classify compounds as efflux substrates (active in tolC only) or efflux evaders (active in both WT and tolC) using stringent activity thresholds.

- Apply matched molecular pair analysis to identify structural modifications that convert efflux substrates into evaders [7].

Physicochemical Property Analysis

- Calculate key molecular descriptors (logD, polar surface area, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors) for active and inactive compounds.

- Use machine learning to identify chemical features correlated with improved Gram-negative activity and reduced efflux recognition [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating the Gram-Negative Cell Envelope

| Reagent/Cell Line | Specific Function | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli MG1655 (WT) | Model Gram-negative organism | Baseline for phenotypic comparisons; genetic background for mutant construction | Well-characterized K-12 strain; amenable to genetic manipulation |

| E. coli tolC mutant | Deficient in major efflux conduit | Identification of efflux pump substrates; studies of efflux-mediated resistance | Hyper-susceptible to many antibiotics; used in efflux classification assays |

| E. coli lpxC mutant | Reduced LPS in outer membrane | Studies of outer membrane permeability barrier; identification of permeation-limited compounds | Temperature-sensitive; requires specific growth conditions |

| Porin-specific antibodies | Immunodetection of OMP expression | Quantification of porin expression levels in clinical isolates; monitoring porin regulation | Commercial availability varies; requires validation for different bacterial species |

| Fluorescent membrane dyes (SYTOX, PI) | Indicators of membrane integrity | Assessment of envelope damage in mutant strains; evaluation of membrane-targeting compounds | Differential permeability characteristics; compatibility with fluorescence detection |

| β-lactamase substrates (Nitrocefin) | Chromogenic β-lactamase detection | Measurement of β-lactamase activity in periplasmic extracts; enzyme kinetics | Real-time colorimetric change; useful for high-throughput screening |

The Gram-negative cell envelope represents one of nature's most effective protective barriers, enabling bacterial survival in hostile environments, including those containing therapeutic concentrations of antibiotics. Its multi-layered architecture, combining a restrictive outer membrane, enzymatic defenses in the periplasm, and powerful efflux systems, creates a formidable obstacle for antibiotic penetration and retention. Addressing the challenge of Gram-negative resistance requires integrated approaches combining structural biology, genetics, computational modeling, and advanced chemical design. Future research must focus on identifying novel targets within the envelope assembly pathways, developing efflux pump inhibitors for clinical use, and designing next-generation antibiotics that exploit underutilized penetration pathways or are less susceptible to efflux recognition. Only through a fundamental understanding of this impermeable barrier can we hope to develop effective therapeutic strategies against the growing threat of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Gram-negative bacteria represents a critical and escalating global health threat, undermining the efficacy of modern medicine and jeopardizing routine medical procedures [9] [10]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified several Gram-negative pathogens, including Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, as critical priorities for research and development of new therapeutics [9] [11]. The specialized cell envelope of Gram-negative bacteria—comprising an outer membrane (OM) with lipopolysaccharides (LPS), a thin peptidoglycan layer, and an inner membrane (IM)—serves as a formidable permeability barrier and a platform for sophisticated resistance mechanisms [9] [10]. This in-depth technical guide examines the core molecular machinery underpinning the primary defense strategies employed by Gram-negative pathogens: enzymatic inactivation of antibiotics, efflux pump activity, target site modification, and reduced membrane permeability. Understanding these mechanisms at a granular level is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to design novel interventions to combat the silent pandemic of AMR.

Core Resistance Mechanisms: A Molecular Perspective

Enzymatic Inactivation of Antibiotics

Bacteria produce a diverse array of enzymes that inactivate antimicrobial agents through degradation or modification, rendering the drugs ineffective before they reach their cellular targets [12] [11].

β-Lactamases are the most clinically significant group of inactivating enzymes. They hydrolyze the amide bond within the β-lactam ring, a structure central to penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems [12] [11]. The evolution of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), such as TEM and CTX-M, confers resistance to later-generation cephalosporins. Furthermore, carbapenemases (e.g., KPC, NDM, OXA-48) hydrolyze carbapenems, which are often considered last-resort antibiotics [12] [11]. The genes encoding these enzymes are frequently located on plasmids, facilitating their rapid dissemination across bacterial populations through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) [12].

Other enzymatic mechanisms include aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes that catalyze the transfer of functional groups (e.g., acetyl, adenyl, phosphoryl) onto the antibiotic molecule, disrupting its ability to bind to the 16S rRNA of the 30S ribosomal subunit [12].

Table 1: Major Antibiotic-Inactivating Enzymes and Their Targets

| Enzyme Class | Antibiotic Target | Molecular Mechanism | Example Enzymes/Gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Lactamases | β-Lactams (Penicillins, Cephalosporins, Carbapenems) | Hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring [12] [11] | CTX-M (ESBL), KPC, NDM (Carbapenemase) [11] |

| Aminoglycoside Modifying Enzymes | Aminoglycosides (Gentamicin, Amikacin) | Acetylation, adenylation, or phosphorylation of drug molecule [12] | aac, ant, aph [12] |

| Phosphotransferases | Aminoglycosides, Chloramphenicol | Phosphorylation of hydroxyl groups [13] | Not specified in search results |

| Transferases | Polymyxins (Colistin) | Transfer of phosphoethanolamine to lipid A, reducing drug binding [11] | mcr genes [11] |

Efflux Pump Systems

Multidrug efflux pumps are integral membrane proteins that actively export a wide range of structurally diverse antibiotics from the bacterial cell, reducing intracellular concentrations to subtoxic levels [9] [14]. In Gram-negative bacteria, these systems are often tripartite, spanning the entire cell envelope [14].

The Resistance-Nodulation-Division (RND) superfamily includes some of the most clinically relevant efflux systems, such as AcrAB-TolC in E. coli and MexAB-OprM in P. aeruginosa [14]. These complexes consist of an inner membrane transporter (e.g., AcrB), a periplasmic membrane fusion protein (e.g., AcrA), and an outer membrane channel (e.g., TolC) [14]. They utilize the proton motive force to expel antibiotics. Other families include the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) and the ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) superfamily, the latter of which uses ATP hydrolysis for energy [14].

Emerging research continues to identify novel efflux-associated proteins. For instance, the BON (bacterial OsmY and nodulation) domain-containing protein has been shown to form a trimeric, pore-shaped channel that functions in an "one-in, one-out" manner to transport antibiotics like carbapenems, contributing to intrinsic and acquired resistance [14].

Table 2: Major Efflux Pump Families in Gram-Negative Bacteria

| Efflux Pump Family | Energy Source | Key Examples | Antibiotic Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| RND (Resistance-Nodulation-Division) | Proton Motive Force [14] | AcrAB-TolC (E. coli), MexAB-OprM (P. aeruginosa) [14] | β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, chloramphenicol, macrolides [14] |

| MFS (Major Facilitator Superfamily) | Proton Motive Force [14] | Not specified in search results | Tetracyclines, chloramphenicol [14] |

| ABC (ATP-Binding Cassette) | ATP Hydrolysis [14] [11] | Not specified in search results | Aminoglycosides, polymyxins [11] |

| MATE (Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion) | Proton/Sodium Ion Gradient [14] | Not specified in search results | Fluoroquinolones [14] |

| PACE (Proteobacterial Antimicrobial Compound Efflux) | Proton Motive Force [14] | Not specified in search results | Chlorhexidine, acriflavine [14] |

Target Site Modification

Bacteria can alter the structure of an antibiotic's cellular target, diminishing the drug's binding affinity and rendering it ineffective [12] [13]. This can occur through mutation or enzymatic modification of the target.

A classic example is the modification of Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs). In methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), the acquired mecA gene encodes PBP2a, which has low affinity for β-lactam antibiotics [12]. In Gram-negative bacteria, mutations in DNA gyrase (gyrA) and topoisomerase IV (parC) are common mechanisms of resistance to fluoroquinolones [12] [11]. A single point mutation (e.g., C257T in gyrA) can lead to an amino acid substitution (e.g., S83L) that prevents drug binding [11].

Enzymatic modification is exemplified by methylation of the 16S rRNA molecule, which blocks the binding of aminoglycosides [11]. Similarly, mutations in the 23S rRNA or ribosomal proteins L3 and L4 can lead to resistance against macrolides and oxazolidinones [12].

Reduced Permeability

The Gram-negative outer membrane is a formidable permeability barrier that intrinsically protects against many antibiotics [9] [11]. Resistance is often achieved by a reduction in the influx of antimicrobials.

This is primarily mediated through the downregulation, loss, or mutation of porin proteins [9] [11]. Porins, such as OmpF and OmpC in E. coli, form water-filled channels that allow the passive diffusion of hydrophilic molecules, including many antibiotics like β-lactams and fluoroquinolones [9] [11]. Reduced expression of these porins limits the intracellular accumulation of drugs. For example, carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii is linked to the reduced expression of CarO and Omp porins [11]. Similarly, alterations in the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structure can reduce the permeability of the outer membrane to large molecules like vancomycin and the polycationic peptide polymyxins [9] [13].

Diagram 1: Four Core AMR Mechanisms in Gram-Negative Bacteria. This diagram illustrates the primary molecular resistance mechanisms operating within the Gram-negative cell envelope, leading to antibiotic treatment failure.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Resistance Mechanisms

Protocol 1: Frequency of Resistance (FoR) Assay

The FoR assay is a standard method for quantifying the spontaneous development of resistance in a bacterial population upon exposure to an antibiotic [15].

- Culture Preparation: Grow the bacterial strain of interest overnight in a suitable broth (e.g., Mueller-Hinton Broth) under standard conditions.

- Cell Counting: Determine the total viable count (CFU/mL) of the overnight culture by serial dilution and plating.

- Antibiotic Exposure: Plate approximately 10^10 bacterial cells onto agar plates containing the antibiotic at concentrations ranging from the MIC to 4x or 8x the MIC. Also, plate a dilution series onto drug-free agar to determine the exact input CFU.

- Incubation: Incubate the plates for 24-48 hours at the appropriate temperature.

- Calculation: Count the colonies growing on the antibiotic-containing plates. The frequency of resistance is calculated as the number of CFU on the antibiotic plate divided by the total number of CFU plated [15].

- Confirmation: Confirm the resistance level of the resulting mutants by determining their Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and comparing it to the wild-type strain (relative MIC) [15].

Protocol 2: Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE)

ALE experiments simulate long-term exposure to antibiotics to study the evolutionary trajectories of resistance development [15].

- Initial Inoculum: Start with a wild-type, susceptible bacterial strain.

- Passaging: Serially passage the bacteria in the presence of sub-inhibitory and gradually increasing concentrations of the antibiotic. This is typically done over a fixed period (e.g., 60 days or ~120 generations) in liquid culture or on solid agar [15].

- Monitoring: Regularly monitor bacterial growth and adjust the antibiotic concentration to maintain selective pressure. Sample the population at predetermined time points.

- Endpoint Analysis: At the end of the experiment, measure the MIC of the evolved population. Isolate individual clones from the endpoint population for whole-genome sequencing (WGS) to identify mutations (e.g., in target genes, efflux pump regulators, porins) that confer resistance [15].

- Validation: Use genetic techniques, such as gene knockout or complementation, to validate the role of identified mutations in the resistant phenotype.

Diagram 2: Adaptive Laboratory Evolution Workflow. This flowchart outlines the process of using serial passaging under antibiotic pressure to evolve and identify resistance mutations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for AMR Mechanism Research

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function/Application | Specific Example / Context of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CA-MHB) | Standardized medium for antibiotic susceptibility testing (MIC, FoR) [15] | Provides consistent ion concentrations for reliable and reproducible MIC results. |

| Agar Plates with Antibiotic Gradients | For FoR assays and isolating resistant mutants [15] | Used to determine the frequency of spontaneous resistance at specific drug concentrations. |

| PCR & Sanger Sequencing Reagents | To amplify and sequence specific resistance genes (e.g., gyrA, parC, bla genes) [11] | Identifies point mutations (e.g., C257T in gyrA) or the presence of specific β-lactamase genes. |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) Kit | For comprehensive analysis of genomic changes in evolved resistant strains [15] | Used in ALE experiments to discover all chromosomal mutations conferring resistance. |

| Plasmid Extraction Kit | To isolate and characterize mobile genetic elements carrying resistance genes [12] | Essential for studying the horizontal transfer of genes like blaKPC or mcr-1. |

| Real-Time PCR (qPCR) Reagents | To quantify the expression levels of efflux pump genes (e.g., acrB, mexB) or porin genes [11] | Detects upregulation of efflux pumps or downregulation of porins in response to antibiotic stress. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing System | For functional validation of resistance mutations via gene knockout or complementation [10] | Used to confirm the causal role of a specific mutation (e.g., in pmrB) in the resistant phenotype. |

The molecular machinery of defense in Gram-negative bacteria is complex, dynamic, and highly effective. The interplay between enzymatic inactivation, efflux, target modification, and reduced permeability creates a multi-layered shield that significantly complicates treatment. The ongoing discovery of novel resistance proteins, such as BON-domain proteins and potent efflux pump variants like RE-CmeABC, underscores the adaptive ingenuity of bacterial pathogens [14]. For the research community, countering this threat requires a deep and nuanced understanding of these mechanisms, facilitated by robust experimental methodologies like FoR assays and ALE, and empowered by modern tools such as WGS and CRISPR-Cas9. The future of anti-infective therapy lies in developing innovative strategies, such as dual-targeting permeabilizers [15], efflux pump inhibitors, and β-lactamase adjuvants, that can outmaneuver these evolutionary defenses and preserve the utility of our antimicrobial armamentarium.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents a critical global health threat, directly causing an estimated 1.27 million deaths worldwide in 2019 [16]. The rapid evolution and dissemination of resistance among Gram-negative pathogens are largely driven by horizontal gene transfer (HGT), a process that allows for the sharing of genetic material, including antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), between bacteria. This whitepaper details the mechanisms of genetic mobility, focusing on the roles of plasmids, Integrative and Conjugative Elements (ICEs), and other mobile genetic elements (MGEs) in propagating AMR. Framed within a One Health perspective, which recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health, this document synthesizes current research to provide drug development professionals and scientists with a technical guide to the pathways, experimental models, and methodologies essential for combating this crisis [16] [17].

Horizontal gene transfer is a more significant driver of bacterial evolution than random mutation, as it facilitates the acquisition of entire genes, enabling the rapid expression of new resistance phenotypes [18]. In the context of AMR, HGT allows susceptible bacteria to acquire ARGs from resistant neighbors, effectively spreading resistance across different species and genera. This transfer occurs with high frequency in complex microbial communities, such as biofilms, and is exacerbated by selective pressures from antibiotic use [19]. The three primary mechanisms of HGT are:

- Conjugation: The direct, cell-to-cell transfer of genetic material via a conjugative pilus, mediated by plasmids and ICEs.

- Transformation: The uptake and incorporation of free environmental DNA by bacterial cells.

- Transduction: The transfer of bacterial DNA from one cell to another via bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria).

Among these, conjugation is considered the most significant route for the spread of ARGs [18]. The gut of animals and humans, wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), and soil are potent reservoirs where this HGT occurs, acting as breeding grounds for the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens [16] [18] [19].

Key Mobile Genetic Elements and Their Mechanisms

The dissemination of ARGs is facilitated by a suite of MGEs that can move within and between bacterial genomes.

Plasmids

Plasmids are extrachromosomal, self-replicating DNA elements that are cornerstone players in the global spread of AMR.

- Function and Role in AMR: Plasmids often carry accessory genes, including ARGs, that are beneficial to the host bacterium under antibiotic stress. They can transfer these genes across taxonomic boundaries, sometimes over large phylogenetic distances, making them a primary vehicle for ARG dissemination [16].

- Classification and Host Range: Plasmids are broadly categorized based on their ability to self-transfer:

- Conjugative plasmids encode all the necessary machinery (e.g., a Type IV Secretion System, T4SS) for their own transfer via conjugation.

- Mobilizable plasmids possess only an origin-of-transfer (oriT) and can be transferred using the conjugation machinery of a coexisting conjugative plasmid.

- Non-mobilizable plasmids lack the genes for transfer [16]. Some plasmids, known as broad-host-range (BHR) plasmids (e.g., IncP-1), can replicate in a wide variety of bacterial species, dramatically expanding the potential reservoir for ARGs [16].

- Resistance Islands and Mosaic Plasmids: Plasmids are highly dynamic. A recent analysis of 6,784 plasmids from Escherichia, Salmonella, and Klebsiella isolates found that 84% of ARGs in MDR plasmids are clustered in resistance islands [20]. These islands are agglomerations of ARGs and other MGEs, such as insertion sequences (IS) and transposons, which facilitate the copying and shuffling of genes between DNA molecules. This results in the creation of mosaic plasmids—genetic elements composed of parts from distinct sources, which are common in clinical genera like Escherichia and Klebsiella [16] [20].

Integrative and Conjugative Elements (ICEs)

ICEs are mobile genetic elements that reside integrated into the host bacterium's chromosome but can excise themselves, form a circular intermediate, and be transferred via conjugation.

- Function and Role in AMR: Like plasmids, ICEs contain genes required for their own excision, transfer, and integration. They are modular and can acquire new genes, including ARGs, through recombination [18]. Unlike plasmids, ICEs replicate as part of the host chromosome and do not exist as extrachromosomal elements for most of their life cycle.

- Mechanism of Integration and Transfer: Integration into specific target DNA sequences is typically dependent on attachment sites (attP on the ICE and attB on the chromosome) and is mediated by integrases. Upon excision, the ICE transfers to a recipient cell and integrates into its chromosome, often in a site-specific manner, though some ICEs use DDE recombinases for site-independent integration [18].

Integrons

Integrons are genetic assembly platforms that are not mobile themselves but are frequently carried on plasmids and ICEs. They play a central role in the acquisition and expression of ARGs.

- Structure and Function: An integron is defined by the presence of:

- An integrase gene (intI), which catalyzes site-specific recombination.

- A primary recombination site (attI).

- A promoter (Pc) that drives expression of captured genes [17].

- Gene Cassette Capture and Expression: Integrons can capture promoterless gene cassettes, which typically contain a single ARG and an associated recombination site (attC). The integrase enzyme integrates these cassettes at the attI site, allowing them to be expressed from the common Pc promoter. This system functions as a natural cloning and expression system, enabling bacteria to stockpile and express multiple ARGs from a single platform [17]. Class 1 integrons are frequently associated with AMR in human pathogens and are considered a dangerous pool of resistance determinants from a One Health perspective [17].

Table 1: Key Mobile Genetic Elements in AMR Dissemination

| Element | Genetic Nature | Mobility | Primary Role in AMR | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid | Extrachromosomal DNA | Conjugative, Mobilizable, or Non-mobilizable | Primary vehicle for intercellular ARG transfer | Broad-host-range variants; carries resistance islands; mosaic structure [16] [20] |

| ICE | Chromosomally integrated | Conjugative (upon excision) | Horizontal transfer of ARGs from the chromosome | Modular structure; site-specific integration; replicates with chromosome [18] |

| Integron | Platform on MGEs | Non-mobile (hitchhikes on plasmids/ICEs) | Acquisition and expression of ARG cassettes | Natural gene capture system; common in clinical isolates (e.g., Class 1) [17] |

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of conjugative plasmid transfer, a primary pathway for AMR dissemination.

Quantitative Analysis of ARG Distribution and Mobility

Understanding the prevalence and genetic organization of ARGs is crucial for assessing their dissemination risk. Large-scale genomic analyses reveal clear patterns.

- Dominance of Resistance Islands: As noted, the vast majority (84%) of ARGs in MDR plasmids from key Gram-negative genera are organized in compact resistance islands within collinear syntenic blocks (CSBs). These CSBs have a median length of 8 genes, with 65% comprising 10 or fewer genes, indicating dense clustering of resistance determinants [20].

- Association with Mobile Genetic Elements: The evolution of these resistance islands is driven by specific MGEs. Analysis has identified 76 gene families encoding site-specific recombinases (SSRs) and transposases that co-occur with ARGs within these islands. The most frequent SSR gene families associated with ARG islands include IS26, Tn3 transposase, and class 1 integron integrase, which collectively comprise 66% of the SSR genes found in plasmid-borne resistance islands [20].

- Barriers to Dissemination: The agglomeration of ARGs is biased towards specific plasmid lineages. Resistance islands identified in one plasmid lineage are rarely shared among distantly related plasmids, suggesting barriers to ARG dissemination between plasmid types, potentially related to plasmid genetic properties, host range, and evolutionary history [20].

Table 2: Prevalence of Key Mobile Genetic Elements in Antibiotic Resistance Islands (Based on KES Plasmid Analysis)

| Mobile Genetic Element Type | Specific Gene Family Example | Function | Approximate Contribution to SSR Genes in Resistance Islands |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDE Transposase | IS26, IS6100 | DNA cutting and pasting via DDE enzymatic activity | 66% (collectively for top families) [20] |

| Serine Recombinase | Tn3 Resolvase | Resolution of co-integrate structures during transposition | |

| Tyrosine Recombinase | Class 1 Integron Integrase | Site-specific integration of gene cassettes | |

| HUH Endonuclease | IS91 Transposase | Replication and single-stranded DNA transfer |

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Studying HGT

Research into HGT and AMR dissemination relies on a combination of in silico, in vitro, and in vivo models, each offering unique insights.

In Silico and Genomic Analyses

Computational methods are indispensable for large-scale analysis of MGEs and HGT patterns.

- Methodology: Large datasets of bacterial genomes and plasmids are assembled. Protein-coding genes are clustered into homologous families, and ARGs are identified using specialized databases like the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD). Algorithms are then used to identify collinear syntenic blocks (CSBs) of co-occurring ARGs and MGEs to define resistance islands and quantify their distribution across plasmid taxonomic units (PTUs) [20].

In Vitro Models

- Standard Conjugation Assay: This is a fundamental protocol for measuring plasmid transfer frequencies.

- Procedure: Donor and recipient strains are grown separately to mid-log phase, mixed at a specific ratio (e.g., 1:10 donor to recipient), and allowed to conjugate on a filter placed on solid agar or in a liquid medium for a set period. The mixture is then resuspended, diluted, and plated on selective media that counterselects against the donor and the recipient while allowing transconjugants (successful recipient cells that acquired the plasmid) to grow. The transfer frequency is calculated as the number of transconjugants per recipient [18].

- Key Reagents: Selective antibiotics, solid agar media, membrane filters.

- Biofilm Models: As HGT occurs more frequently in biofilms than in planktonic culture, these models are critical.

- Procedure: Biofilms are cultivated in flow cells, on pegs (e.g., Calgary Biofilm Device), or in microtiter plates. Donor and recipient strains are co-cultured to form a biofilm. After incubation, the biofilm is disaggregated, and transconjugants are enumerated by plating on selective media, similar to the standard conjugation assay [19].

- Key Reagents: Flow cells, peg lids, specialized growth media for biofilm formation (e.g., with low nutrient levels).

- Morbidostat-Based Resistomics Workflow: This sophisticated approach studies the evolution of resistance in real-time.

- Procedure: A morbidostat is a computer-controlled continuous culturing device that constantly monitors bacterial growth (via OD600) and dynamically adjusts the concentration of an antimicrobial agent in the media. If bacteria grow faster than the dilution rate, the drug concentration is increased; if growth slows, the drug concentration is decreased. This applies gradual selective pressure, driving the evolution of resistance. Evolved isolates are periodically sequenced to identify resistance-conferring mutations [21].

- Key Reagents: Morbidostat device, antimicrobial agent of interest (e.g., novel drug TGV-49), sequencing reagents.

In Vivo Models

Studying HGT in a live host provides the most clinically relevant context but is also the most complex.

- Animal Models: Common models include mice (Mus musculus), rats (Mus rattus), chickens (Gallus gallus), and insects like fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster). These models allow researchers to investigate how host factors (immunity, diet, gut microbiota) influence conjugation and the transfer of ARGs in the gut and other body sites [18].

The workflow for a typical morbidostat experiment, used to study resistance evolution, is detailed below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for HGT and AMR Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Selective Media & Antibiotics | Selection and counterselection of donor, recipient, and transconjugant bacteria in conjugation experiments. | Plating bacterial mixtures from a conjugation assay to quantify transconjugants [18]. |

| Morbidostat Device | Continuous culturing with automated feedback to maintain bacterial growth under constant drug pressure, driving experimental evolution. | Studying the development of resistance to a novel antimicrobial agent like TGV-49 in Acinetobacter baumannii [21]. |

| Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) | A curated resource of ARGs, their products, and associated phenotypes for in silico identification of resistance determinants. | Annotating ARGs in whole genome sequences of bacterial isolates or plasmids [20]. |

| Microfluidic Chips & Flow Cells | Creating controlled, small-scale environments for studying biofilm development and HGT under fluid shear stress. | Observing real-time conjugation events within a structured multispecies biofilm [19]. |

| Class 1 Integron-Specific Primers/Probes | PCR-based detection and surveillance of a clinically prevalent integron class that is a major reservoir for ARG cassettes. | Screening clinical or environmental isolates for the presence and cassette content of class 1 integrons [17]. |

The battle against antimicrobial resistance necessitates a deep understanding of the genetic mobility facilitated by plasmids, ICEs, and integrons. The quantitative data confirms that ARGs are not randomly distributed but are concentrated in resistance islands within specific plasmid lineages, driven by the activity of MGEs like IS26 and integrons. Combating this threat requires a multi-pronged approach: leveraging advanced experimental models like the morbidostat to predict resistance evolution, employing genomic surveillance to track the spread of high-risk MGEs, and developing novel therapeutic strategies that target the conjugation machinery or the stability of MGEs themselves. Through the collaborative efforts of researchers and drug development professionals, informed by the intricate mechanisms detailed in this whitepaper, we can work towards mitigating the global AMR crisis.

The World Health Organization (WHO) Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (BPPL) for 2024 categorizes antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens into critical, high, and medium priority groups to guide research, development, and public health interventions against antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [22]. Among the most critical threats are Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens—Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacterales (including Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter spp.)—notorious for their ability to "escape" biocidal action and rapidly develop multidrug resistance [23] [24]. These organisms employ sophisticated resistance mechanisms, including enzymatic antibiotic inactivation, efflux pumps, and target site modifications, leading to persistently high mortality rates in healthcare settings worldwide [25] [23]. Surveillance data from 2023, encompassing over 23 million confirmed infections across 104 countries, underscores the escalating global burden, necessitating enhanced stewardship, innovative therapeutics, and robust surveillance systems [26]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of these priority pathogens, detailing their global resistance profiles, molecular resistance mechanisms, and standardized experimental methodologies essential for advancing AMR research.

Global Priority Classifications and Resistance Burden

The WHO 2024 BPPL builds upon its 2017 predecessor, refining the prioritization of 24 antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens across 15 families to address evolving AMR challenges [22]. This list serves as a critical tool for directing research and development (R&D) efforts and investments, particularly targeting developers of antibacterial medicines, academic institutions, and policymakers [22].

Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales are ranked as critical priority pathogens due to their extensive multidrug resistance and significant associated mortality [22] [23]. The ESKAPE group collectively represents leading causes of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), with substantial prevalence in intensive care units (ICUs) and among immunocompromised patients [25] [27].

Table 1: Global Resistance Profiles of WHO-Critical Gram-Negative ESKAPE Pathogens

| Pathogen | Key Resistance Phenotype | Prevalence & Burden | Noteworthy Resistance Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Carbapenem-resistant | 33.9% prevalence in ICU isolates (10-yr study) [27]; 100% MDR rate in SSI isolates [24] | Universal MDR; high resistance to levofloxacin (97.1%), cefepime (94.4%) [23] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Carbapenem-resistant, MDR | 28.3% prevalence in ICU isolates [27]; lower overall AMR but significant in SSIs [24] | Preserved colistin susceptibility; notable ceftriaxone resistance (75%) [23] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Carbapenem-resistant (CRKP), ESBL-producing | 25.6% prevalence in ICU isolates [25]; 88.2% MDR rate in SSIs [24] | Rising carbapenemase-producers (including dual NDM+OXA-48); ampicillin/ceftazidime resistance >93% [25] [23] |

| Enterobacter spp. | Carbapenem-resistant | 7.4% prevalence in ICU isolates [27]; fully carbapenem-susceptible in some cohorts [25] | Variable resistance profiles; concerning potential for ESBL and carbapenemase production [22] |

The economic and clinical impact of infections caused by these pathogens is profound. Patients with HAIs experience significantly longer hospital stays (averaging 20.3 days versus 8.7 days for non-infected patients) and generate substantially higher healthcare costs [25]. In 2019, AMR was directly responsible for 1.27 million deaths globally and contributed to nearly 5 million more [23].

Molecular Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance

Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens deploy a complex arsenal of resistance mechanisms, which can be intrinsic (innate to the species), acquired (via mutation or horizontal gene transfer), or adaptive (in response to environmental pressure) [23].

Key Resistance Pathways and Mechanisms

The primary molecular strategies employed by these bacteria include:

- Enzymatic Inactivation of Antibiotics: Production of β-lactamases, including extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), AmpC cephalosporinases, and carbapenemases (e.g., KPC, NDM, OXA-48-like), which hydrolyze and inactivate β-lactam antibiotics [23]. The Aztreonam-Avibactam combination, for instance, is designed to overcome this by combining a monocyclic β-lactam (stable against metallo-β-lactamases) with a non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitor (avibactam) that inactivates serine-based enzymes [28] [29].

- Reduced Drug Permeability: The asymmetric, double-membrane structure of Gram-negative bacteria, with narrow porin channels, significantly restricts antibiotic penetration into the cell [23].

- Efflux Pump Systems: Overexpression of multi-component efflux pumps (e.g., AcrAB-TolC in Enterobacterales, MexAB-OprM in P. aeruginosa) actively exports a wide range of antibiotics from the cell, contributing to multidrug resistance [23].

- Target Site Modification: Mutations in genes encoding antibiotic target sites, such as penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), DNA gyrase, or topoisomerase IV, reduce drug binding affinity [23].

These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive; their convergence in a single bacterial cell often results in difficult-to-treat multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR), or even pandrug-resistant (PDR) phenotypes [23].

Diagram Title: Core AMR Mechanisms in WHO-Critical Gram-Negative Pathogens

Experimental Evolution of Resistance

Laboratory evolution studies demonstrate that Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens can develop resistance to both established antibiotics and novel drug candidates within a remarkably short timeframe. Research shows that within 60 days (approximately 120 generations) of controlled antibiotic exposure, bacteria can achieve a median 64-fold increase in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) [30].

These studies reveal that resistance mutations selected in the laboratory are frequently already present in natural pathogen populations. This indicates that clinical resistance can emerge rapidly through the selection of pre-existing genetic variants rather than requiring de novo mutation [30]. Furthermore, mobile resistance genes (ARGs) effective against antibiotic candidates are prevalent not only in clinical isolates but also in environmental and human gut microbiomes, facilitating their global dissemination [30].

Surveillance and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

Continuous, standardized surveillance is the cornerstone for understanding AMR epidemiology, informing empirical therapy, and guiding stewardship interventions [25]. The WHO Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) report for 2025 provides a critical analysis of antibiotic resistance prevalence and trends, drawing from over 23 million bacteriologically confirmed cases from 110 countries [26].

Standardized Methodologies for AST

Table 2: Core Methodologies for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing & Surveillance

| Method/Technique | Core Function/Purpose | Key Procedural Steps | Interpretive Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broth Microdilution | Reference quantitative method for determining Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) [21] | 1. Prepare serial dilutions of antimicrobial in broth. 2. Inoculate with standardized bacterial suspension. 3. Incubate (e.g., 35°C, 16-20 hrs). 4. Determine MIC as lowest concentration inhibiting visible growth [21]. | CLSI M27-A3 / EUCAST guidelines [21]. |

| Disk Diffusion (Kirby-Bauer) | Qualitative/semi-quantitative susceptibility testing [24] | 1. Inoculate Mueller-Hinton agar plate. 2. Apply antibiotic-impregnated disks. 3. Incubate (35°C, 16-18 hrs). 4. Measure zone diameters of inhibition [24]. | CLSI / EUCAST breakpoint tables [24]. |

| Automated Systems (e.g., VITEK 2) | High-throughput, automated AST and bacterial identification [25] | 1. Load standardized bacterial suspension into AST card. 2. Insert into instrument. 3. System monitors growth kinetically via optical changes. 4. Software reports MIC and susceptibility category [25]. | Built-in interpretive algorithms based on CLSI/EUCAST. |

| Phenotypic Confirmatory Tests | Detect specific resistance mechanisms (e.g., ESBL, carbapenemase) [25] | ESBL: Double-disk synergy test (DDST) with clavulanate [25]. Carbapenemase: Modified Carbapenem Inactivation Method (mCIM) or molecular assays [25]. | CLSI-defined criteria for synergy or inhibition. |

| Molecular Detection (PCR, LFA) | Identify specific resistance genes (e.g., blaKPC, blaNDM) [25] | 1. Extract bacterial DNA. 2. Amplify target genes via PCR or isothermal methods. 3. Detect amplicons via electrophoresis or lateral flow immunoassay (LFA) [25]. | Positive/internal control amplification. |

Workflow for Integrated Pathogen Surveillance

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow for processing clinical specimens to characterize WHO-priority pathogens, integrating identification, AST, and resistance mechanism detection.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Laboratory Surveillance of Priority Pathogens

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies and Resistance

The development of novel antimicrobial agents is a critical frontline defense against MDR Gram-negative pathogens. Promising strategies include combination therapies with novel β-lactamase inhibitors and agents with new mechanisms of action, such as membrane-targeting compounds.

Aztreonam-avibactam represents a significant advancement for treating infections caused by metallo-β-lactamase (MBL)-producing Enterobacterales. Aztreonam is stable against MBLs, while avibactam inhibits accompanying serine β-lactamases (e.g., ESBLs, KPC) [28] [29]. Analysis of 70 in vitro studies encompassing 490,231 Enterobacterales isolates found resistance to aztreonam-avibactam to be very rare (0-1.8%) in consecutive (non-selected) clinical isolates [28] [29]. However, higher resistance rates are noted in preselected multidrug-resistant strains and among lactose non-fermenters like Acinetobacter baumannii, underscoring the necessity for ongoing susceptibility testing [28].

Novel compounds like TGV-49, a broad-spectrum antimicrobial derived from Mul-1867, exhibit a unique membrane-disrupting mechanism. Its positively charged hexanediamine groups bind to negatively charged membrane components, while hydrazine groups react with carbonyl groups, collectively causing membrane disruption, content leakage, and cell lysis [21]. Experimental evolution of A. baumannii against TGV-49 using a morbidostat device revealed minimal development of resistance, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic alternative [21].

Despite these innovations, a systematic evaluation of 13 antibiotics introduced post-2017 or in development revealed that they are, on average, equally prone to de novo resistance evolution as traditional antibiotics in laboratory settings [30]. This highlights the relentless capacity of bacterial evolution and the need for strategies that proactively anticipate and counter resistance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AMR Studies

| Reagent / Material | Core Function in Research | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Mueller-Hinton Broth/Agar | Standardized medium for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST). | Determining MIC by broth microdilution; conducting disk diffusion assays [21] [24]. |

| CLSI / EUCAST Panels | Reference antibiotic powders and predefined panels for AST. | Generating standardized MIC data against a range of antibiotics [21]. |

| VITEK 2 AST Cards | Automated, cartridge-based panels for high-throughput AST. | Rapid phenotypic profiling of clinical isolates (e.g., AST-N331 for Gram-negatives) [25]. |

| MALDI-TOF MS Reagents | Matrix and calibration standards for mass spectrometry. | Rapid, accurate identification of bacterial pathogens from culture [25]. |

| PCR Master Mixes & Primers | Reagents for amplification of DNA. | Detecting specific resistance genes (e.g., blaKPC, blaNDM, mecA) [25]. |

| Morbidostat Device | Computer-controlled continuous culturing bioreactor for experimental evolution. | Studying resistance development under controlled, escalating antibiotic pressure [21] [30]. |

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CAMHB) | Broth for AST, adjusted for divalent cations to standardize results. | Reference method AST, particularly for cationic antibiotics like colistin [25]. |

| Quality Control Strains | Reference strains (e.g., P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, E. coli ATCC 25922). | Ensuring accuracy and precision of AST methods and reagent performance [25]. |

From Bench to Bedside: Detection, Surveillance, and Current Treatment Paradigms

The escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), particularly in Gram-negative bacteria, represents one of the most serious global health threats of our time [1]. Gram-negative pathogens, with their complex cell envelope structure and sophisticated resistance mechanisms, have become increasingly resistant to nearly all available antibiotic classes, culminating in rising mortality rates worldwide [31]. In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a list of priority pathogens, predominantly Gram-negative species, categorized by the urgency of need for new treatments [1]. Despite this warning, the progress in generating new therapeutic options has proven insufficient, with AMR continuing to escalate as a "global ticking time bomb" [1].

The development of innovative antibacterial agents is hampered by both scientific and economic challenges. The unique structure of the Gram-negative cell envelope, comprising an outer membrane with lipopolysaccharides, a thin peptidoglycan layer, and an inner membrane, creates a formidable permeability barrier that naturally limits drug access [1] [31]. Furthermore, bacteria employ four primary resistance mechanisms: drug inactivation through enzymes like β-lactamases; reduced drug uptake via porin remodeling; enhanced efflux pump activity; and alteration of antibiotic target sites [1] [32]. Meanwhile, the antibacterial development pipeline faces a dual crisis of scarcity and lack of innovation, with many large pharmaceutical companies having de-invested in antibiotic research due to limited economic returns [33] [34].

This whitepaper provides a comprehensive analysis of the current clinical pipeline for antibacterial agents, encompassing both traditional and non-traditional approaches, with a specific focus on combating resistant Gram-negative pathogens. We examine quantitative data on agents in development, detail emerging therapeutic modalities, and present standardized methodological frameworks for their evaluation, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a strategic overview of this critical landscape.

Analysis of the Current Clinical Development Pipeline

The Shrinking Traditional Antibiotic Pipeline

According to the latest WHO analysis from 2025, the clinical pipeline for antibacterial agents is contracting and lacks sufficient innovation to address the most dangerous drug-resistant bacteria [33]. The number of antibacterials in clinical development has decreased from 97 in 2023 to 90 in 2025 [33] [35]. Among these 90 agents, only 50 are traditional antibacterial agents, while 40 employ non-traditional approaches such as bacteriophages, antibodies, and microbiome-modulating agents [33]. This decline occurs despite the growing threat of AMR, which was associated with over 6 million deaths in 2019 alone [36].

Most concerning is the limited activity against critical priority pathogens. Of the 90 agents in development, only 15 are considered truly innovative, and for 10 of these, available data are insufficient to confirm the absence of cross-resistance [33]. Merely 5 of the agents in development demonstrate effectiveness against at least one of the WHO "critical" priority pathogens - the highest risk category that includes carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacteriaceae [33]. The preclinical pipeline remains more active, with 232 programs across 148 groups worldwide, though 90% of these companies are small firms with fewer than 50 employees, highlighting the fragility of the research and development ecosystem [33].

Table 1: Analysis of the Clinical Antibacterial Pipeline (2025 WHO Data)

| Pipeline Category | Number of Agents | Key Characteristics | Activity Against WHO Critical Pathogens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Clinical Pipeline | 90 | Decreased from 97 in 2023 | Limited |

| Traditional Agents | 50 | Small-molecule drugs | 45 target priority pathogens (18 focused on drug-resistant M. tuberculosis) |

| Non-Traditional Agents | 40 | Bacteriophages, antibodies, microbiome modulators | Varies by approach |

| Innovative Agents | 15 | Novel mechanisms/chemical classes | Only 5 effective against ≥1 critical pathogen |

| Preclinical Programs | 232 | Across 148 groups | Heavy focus on Gram-negative pathogens |

Categorization of Therapeutic Development Approaches

Antibacterial agents in development can be classified according to their structural characteristics and therapeutic goals, though the distinction between "traditional" and "non-traditional" has limited regulatory relevance [34]. A more instructive framework categorizes both traditional and non-traditional products into four development archetypes known as the STAR categories [34]:

- Standalone: Products effective as monotherapy, including most traditional small molecules and some direct-acting bactericidal products with non-traditional structures.

- Transform: Products that extend the activity range of an existing drug to enable action against previously insusceptible microorganisms.

- Augment: Products that improve the activity of an otherwise effective antibiotic, such as those reducing bacterial virulence or neutralizing toxins.

- Restore: Products that reinstate the efficacy of existing drugs that have lost effectiveness due to resistance development (e.g., β-lactamase inhibitors).

This categorization helps identify appropriate regulatory pathways and clinical trial designs for different therapeutic approaches, with non-inferiority trials generally appropriate for Standalone, Transform, and Restore categories, while superiority designs may be needed for Augment products [34].

Emerging Non-Traditional Antibacterial Approaches

Bacteriophage Therapy

Bacteriophage (phage) therapy represents one of the most clinically advanced non-traditional approaches, with a wealth of evidence from compassionate use cases against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections [36]. Phages are viruses that specifically infect and lyse bacteria through a precise mechanism: tail fibers recognize and adsorb to host cell receptors, followed by genome ejection into the cytoplasm. The phage then utilizes host machinery to replicate, ultimately inducing cell lysis through endolysins that degrade peptidoglycan [36].

Two predominant development models exist for phage therapy. The first involves on-demand phage cocktails formulated based on susceptibility testing of the patient's specific isolate against phage banks [36]. The Magistral Phage system in Belgium exemplifies a successful regulatory model for this personalized approach. The second model employs fixed-composition phage products designed to treat specific pathogens or conditions, which offers a clearer regulatory pathway but cannot adapt to emerging strains [36]. Currently, the FDA has not approved any phage product for clinical use, though over a dozen commercial phage products against Gram-negative bacteria are in phase I-III trials targeting various infections including lung infections, urinary tract infections, and chronic wounds [36].

Clinical evidence primarily stems from compassionate use cases where all antibiotic options have been exhausted. Phage therapy has demonstrated efficacy against a wide variety of Gram-negative infections including those caused by E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and A. baumannii, with the majority of case studies targeting P. aeruginosa [36]. Administration routes are tailored to infection sites—intravenous for systemic infections, inhalation for respiratory infections, and topical for wound infections. A recent retrospective study of 100 consecutive phage therapy cases revealed clinical improvement and bacterial eradication in 77.2% and 61.3% of infections, respectively, highlighting the importance of concurrent antibiotics for optimal outcomes [36].

Table 2: Emerging Non-Traditional Antibacterial Approaches Against Gram-Negative Pathogens

| Therapeutic Approach | Mechanism of Action | Development Stage | Key Examples/Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteriophage Therapy | Lytic phage replication and bacterial lysis | Compassionate use; Phase I-III trials | OMKO1 phage targeting P. aeruginosa porin M |

| Anti-Virulence Agents | Target virulence factors without killing | Preclinical; early clinical | Quorum sensing inhibitors; toxin neutralization |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Neutralize specific bacterial toxins | Approved for specific toxins | Raxibacumab (anthrax toxin); bezlotoxumab (C. difficile toxin) |

| Microbiome-Modifying Therapies | Restore protective commensal microbiota | Phase I-III trials | Fecal microbiota transplantation; defined consortia |

| Antimicrobial Peptides | Membrane disruption; immunomodulation | Preclinical; early clinical | Naturally derived peptides; synthetic analogs |

| Nanomaterial-Based Therapies | Physical membrane disruption; targeted delivery | Preclinical | Metal nanoparticles; functionalized liposomes |

Other Promising Non-Traditional Modalities

Beyond phage therapy, several other non-traditional approaches show promise for combating resistant Gram-negative infections:

Anti-virulence therapies aim to disarm pathogens rather than kill them, potentially reducing selective pressure for resistance [37]. These agents target bacterial virulence mechanisms including toxin production, secretion systems, adhesion factors, and quorum-sensing communication systems [37]. For instance, quorum sensing inhibitors disrupt the chemical signaling pathways that coordinate bacterial pathogenicity and biofilm formation [32].

Immunotherapy approaches leverage or enhance the host immune response against bacterial pathogens [36]. This includes monoclonal antibodies targeting specific bacterial surface antigens or toxins, such as raxibacumab for anthrax toxin and bezlotoxumab for Clostridium difficile toxin [34]. These approaches offer high specificity and can neutralize the most damaging aspects of bacterial infections.

Microbiome-modifying therapies seek to restore protective commensal communities to prevent colonization by resistant pathogens [36] [34]. Fecal microbial transplantation has proven highly effective against recurrent C. difficile infections, and research is ongoing to develop defined consortia of beneficial bacteria for other clinical applications [36].

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and nanomaterial-based therapies represent additional innovative approaches [32] [36]. AMPs are naturally occurring or synthetic peptides that can disrupt bacterial membranes or modulate immune responses, while engineered nanoparticles can physically damage bacterial membranes or serve as targeted delivery vehicles for conventional antibiotics [32].

Resistance Mechanisms in Gram-Negative Bacteria and Therapeutic Implications

The effectiveness of both traditional and non-traditional antibacterial agents is fundamentally challenged by the sophisticated resistance mechanisms of Gram-negative bacteria. These mechanisms can be categorized into four primary groups that impact drug efficacy through different pathways [1] [31].

Enzymatic inactivation represents a foremost resistance mechanism, particularly β-lactamases that hydrolyze the β-lactam ring of penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems [1] [32]. The evolution of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases (such as KPC, NDM, and OXA-48) has severely limited treatment options for common Gram-negative pathogens [31] [32]. Newer β-lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations aim to counter this mechanism, but emerging resistance to these combinations underscores the continuous evolutionary battle [38].

Reduced drug uptake occurs through modifications to the Gram-negative outer membrane, particularly changes in porin proteins that serve as entry channels for hydrophilic antibiotics [1] [32]. Mutations in non-specific porins like OmpF can confer resistance to multiple antibiotic classes, including β-lactams and fluoroquinolones [32]. Additionally, structural modifications to lipopolysaccharides can reduce membrane permeability to hydrophobic compounds [31].

Efflux pump systems actively export antibiotics from the bacterial cell, maintaining subtherapeutic intracellular concentrations [1] [32]. Resistance-nodulation-division (RND) superfamily pumps are particularly effective in Gram-negative bacteria and can recognize a wide range of structurally unrelated antimicrobials, contributing to multidrug resistance phenotypes [32]. These pumps often work synergistically with reduced influx mechanisms to confer high-level resistance.

Target site modifications protect essential bacterial structures from antibiotic binding without affecting bacterial viability [32]. Mutations in genes encoding antibiotic targets—such as DNA gyrase (fluoroquinolone target), penicillin-binding proteins (β-lactam targets), and ribosomal components (aminoglycoside targets)—can reduce drug affinity and confer resistance [31] [32]. These alterations often arise through spontaneous mutation and selective pressure during antibiotic treatment.

The alarming spread of resistance genes through horizontal gene transfer via plasmids, transposons, and integrons further accelerates the dissemination of these resistance mechanisms among bacterial populations [1]. This genetic mobility, combined with selective pressure from antibiotic use, has created a perfect storm for the rapid global spread of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens.

Experimental Frameworks and Research Methodologies

Standardized Susceptibility Testing Protocols

Accurate assessment of bacterial susceptibility to both traditional and non-traditional agents requires standardized methodologies. For conventional antibiotics, the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) provides reference methods including broth microdilution and disk diffusion [38]. These protocols involve:

- Bacterial Inoculum Preparation: Adjusting bacterial suspensions to a standardized turbidity (0.5 McFarland standard, approximately 1-2 × 10^8 CFU/mL) in appropriate media [38].

- Antibiotic Dilution Series: Preparing two-fold serial dilutions of antibiotics in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth for minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination [38].

- Inoculation and Incubation: Adding standardized bacterial inoculum to antibiotic dilutions and incubating at 35±2°C for 16-20 hours [38].

- Endpoint Determination: MIC is defined as the lowest concentration that completely inhibits visible growth [38].

For non-traditional agents, modified approaches are often required. For phage therapy, susceptibility testing typically involves spot testing or efficiency of plating assays to determine the host range of phages against clinical isolates [36]. For β-lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, the broth disk elution method has been endorsed by CLSI to test the activity of ceftazidime-avibactam in combination with aztreonam against metallo-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales [38].

Clinical Trial Design Considerations

Developing appropriate clinical trial designs for novel antibacterial agents presents unique challenges. For traditional antibiotics with direct bactericidal activity, non-inferiority trials are often appropriate when effective standard treatments exist [34]. These designs aim to demonstrate that the new agent is not unacceptably less effective than existing therapy. Key considerations include:

- Non-inferiority Margin Selection: Based on historical evidence of drug efficacy and clinical judgement about acceptable loss of efficacy [34].

- Patient Population Definition: Typically focused on specific infection sites (e.g., complicated urinary tract infections, hospital-acquired pneumonia) with microbiological confirmation of causative pathogens [34].

- Endpoint Selection: Often composite endpoints incorporating clinical and microbiological outcomes at a defined test-of-cure visit (typically 7-14 days after end of treatment) [34].

For agents with non-traditional goals or mechanisms, alternative endpoints may be necessary. Anti-virulence agents that don't directly kill bacteria may require demonstration of reduced disease severity or complication rates [34]. Microbiome-modifying therapies might be evaluated based on colonization resistance or reduction in recurrent infections [34]. In some cases, innovative trial designs such as platform trials or studies using external controls may be appropriate, particularly for pathogens with limited treatment options [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Antibacterial Development

| Reagent/Platform | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth | Standardized medium for antibiotic susceptibility testing | CLSI-recommended for broth microdilution MIC determination |

| PCR and sequencing reagents | Detection and characterization of resistance genes | Identification of blaKPC, blaNDM, blaOXA-48 carbapenemase genes |

| Cell culture models | Assessment of host-pathogen interactions and drug penetration | Human epithelial cell lines for intracellular activity studies |

| Animal infection models | In vivo efficacy assessment | Mouse thigh infection model; neutropenic lung infection models |

| Mass spectrometry systems | Characterization of bacterial metabolites and antibiotic concentrations | LC-MS/MS for therapeutic drug monitoring |

| Flow cytometers | Analysis of bacterial viability and host immune responses | Assessment of membrane permeability and efflux pump activity |

| Biofilm reactors | Study of biofilm-associated infections | CDC biofilm reactor; Calgary biofilm device |

| Genome editing tools | Bacterial gene knockout and modification | CRISPR-Cas9 systems; allelic exchange techniques |

| Protein expression systems | Production of bacterial enzymes for biochemical studies | Recombinant β-lactamase expression for inhibitor screening |

| Artificial intelligence platforms | Drug discovery and resistance prediction | Machine learning for compound screening; AMR gene identification |

The clinical pipeline for antibacterial agents against resistant Gram-negative pathogens remains insufficient despite the escalating global threat of antimicrobial resistance. While the traditional antibiotic pipeline continues to contract, promising non-traditional approaches—particularly bacteriophage therapy, anti-virulence strategies, and immunotherapies—are advancing through clinical development. The continued evolution of sophisticated resistance mechanisms in Gram-negative bacteria, including enzymatic inactivation, efflux pumps, and target site modifications, necessitates innovative therapeutic strategies and robust diagnostic approaches.