Combination Therapy vs Monotherapy: A Comprehensive Analysis of Clinical Outcomes, Mechanisms, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the clinical outcomes of combination therapy versus monotherapy across diverse medical fields including oncology, infectious diseases, and rheumatology.

Combination Therapy vs Monotherapy: A Comprehensive Analysis of Clinical Outcomes, Mechanisms, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the clinical outcomes of combination therapy versus monotherapy across diverse medical fields including oncology, infectious diseases, and rheumatology. Drawing from recent clinical trials, meta-analyses, and real-world evidence, we examine the mechanistic rationales for therapeutic combinations, methodological considerations for their evaluation, and challenges in optimization and value assessment. The analysis reveals that the superiority of combination regimens is highly context-dependent, varying by disease pathology, patient population, and specific therapeutic agents. While significant benefits are demonstrated in areas like oncology and resistant infections, other contexts show comparable efficacy to monotherapy. This review synthesizes evidence-based insights for researchers and drug development professionals to guide future therapeutic strategy development and clinical trial design.

The Rationale and Evidence Base for Combination Therapies Across Disease States

Combination therapy, the use of two or more drugs to treat a single disease, has become a cornerstone for treating complex conditions such as cancer, infectious diseases, and chronic inflammatory disorders. The fundamental premise is that drugs can interact in ways that enhance therapeutic efficacy, reduce adverse effects, or overcome drug resistance. These interactions are systematically categorized based on whether the combined effect exceeds, equals, or falls short of the expected effect based on individual drug potencies. Understanding the mechanistic foundations of these interactions—additive, synergistic, and complementary—is crucial for rational drug design and optimizing clinical treatment regimens [1] [2].

The clinical rationale for exploring drug combinations is compelling. Synergistic interactions allow for the use of lower doses of individual drugs, which can significantly reduce the potential for adverse reactions and mitigate toxicity. Furthermore, combining drugs with different mechanisms of action can counter the emergence of drug resistance, a significant challenge in antimicrobial and anticancer therapies. The quantitative assessment of these interactions is a rigorous process that moves beyond simply adding effect magnitudes; it relies on the concept of dose equivalence and established mathematical models to determine if a combination is truly synergistic [1].

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Conceptual Frameworks for Drug Interactions

The interaction between two or more drugs is defined by how their combined effect deviates from an expected "non-interactive" baseline. The three primary categories are:

- Additive Effect: This occurs when the combined effect of two drugs equals the sum of their individual effects. In this scenario, the drugs are considered to act independently and do not enhance or inhibit each other's activity. The additive effect provides the critical reference point for assessing synergism and antagonism [1] [3].

- Synergistic Effect (Synergism or Supra-Additivity): This is observed when the combined effect of the drugs is greater than the sum of their individual effects. Synergism can significantly enhance therapeutic efficacy, allowing for dose reduction and minimized side effects. It frequently occurs when drugs act through distinct and complementary mechanisms [1] [3].

- Antagonistic Effect: This occurs when the combined effect is less than the sum of the individual effects. One drug interferes with the action of another, potentially compromising the therapeutic outcome. In some cases, this may be exploited to counter toxic effects [4] [2].

It is crucial to distinguish these from complementary drug action, where drugs act on different disease pathways or targets without directly interacting. The overall therapeutic benefit is achieved by addressing the disease's multifactorial nature, as seen in multi-modal pain management or hypertension treatment [2].

Quantitative Models for Assessing Drug Interactions

Quantifying drug interactions requires robust mathematical models that define the expected additive effect. Two predominant models are used:

- Loewe Additivity (Isobolographic Analysis): This model, considered the gold standard, is based on the concept of dose equivalence. The central equation for an additive interaction is ( \frac{a}{A} + \frac{b}{B} = 1 ), where ( a ) and ( b ) are the doses of Drug A and Drug B in the combination that produce a specified effect (e.g., 50% of the maximum effect), and ( A ) and ( B ) are the doses of each drug that produce the same effect when administered alone. A Combination Index (CI) is derived where CI < 1 indicates synergy, CI = 1 indicates additivity, and CI > 1 indicates antagonism [1] [4].

- Bliss Independence: This model defines an additive effect as ( E{A+B} = EA + EB - (EA \times EB) ), where ( E ) represents the fractional effect of each drug alone. The Bliss synergy score is then calculated as ( S = E{A+B} - (EA + EB - EA \times EB) ). A positive S indicates synergy, while a negative S suggests antagonism [4].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and applying these quantitative models in experimental analysis.

Experimental Assessment of Drug Interactions

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Empirically determining drug interactions involves well-established experimental designs that generate data for quantitative analysis using the models above.

Isobolographic Analysis is a foundational experimental design. The workflow involves: (1) establishing dose-effect curves for each drug individually to determine their potencies (e.g., ED50 values); (2) selecting a specific effect level (isobole) for analysis; (3) administering fixed-ratio combinations of the two drugs; (4) measuring the doses of the combination required to achieve the specified effect level; and (5) plotting the experimental dose pairs on the isobologram. A dose pair that falls below the additive line indicates synergism, while a point above the line indicates antagonism [1].

High-Throughput Combinatorial Screening is increasingly used, especially in oncology. This protocol involves: (1) exposing cell lines (e.g., cancer cells) to a matrix of drug concentrations, where each drug is dosed in a gradient along each axis; (2) measuring a phenotypic output like cell growth inhibition or death over a set incubation period (typically 72-144 hours); and (3) generating a dose-response surface. The shape of the contours (isoboles) of this surface is then analyzed to determine the interaction type across a wide range of concentration pairs [4] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful experimentation in drug combination studies relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key materials and their functions in this field.

| Research Reagent/Material | Primary Function in Experiments |

|---|---|

| Cell Lines (e.g., cancer, immortalized) | In vitro model systems for assessing drug effects on proliferation, viability, and mechanistic pathways [4]. |

| Translation-Inhibiting Antibiotics (e.g., tetracycline, chloramphenicol) | Tool compounds for constructing biophysical models of drug interaction on a defined cellular target (the ribosome) [5]. |

| Apoptosis Assay Kits (e.g., caspase-3/7 activation) | Quantify programmed cell death, a key mechanism of action for many chemotherapeutic drug combinations [1]. |

| Multi-Omics Datasets (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) | Provide system-level data to inform computational models and elucidate mechanisms of synergy [4]. |

| Antibody-based Assays (e.g., ELISA for drug trough levels) | Monitor pharmacokinetic parameters, such as infliximab trough levels, critical for assessing combination therapy durability [6]. |

Computational and AI-Driven Prediction of Synergy

The large combinatorial space of potential drug pairs makes empirical screening laborious and resource-intensive. Computational models have emerged as powerful tools for predicting synergistic interactions.

A prominent approach is the integration of multi-omics data. Models like DeepSynergy incorporate features such as gene expression profiles of cell lines, molecular structures of drugs, and protein-protein interaction networks to predict synergy scores. This method has demonstrated superior performance, achieving a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.73 between predicted and measured values [4].

More recently, Large Language Models (LLMs) and other foundation models have been repurposed for synergy prediction. The BAITSAO model, for instance, generates context-enriched embeddings for drugs and cell lines from scientific text. These embeddings, which reflect functional similarities and biological responses, are used to pre-train a unified model for synergy prediction under a multi-task learning framework, showing promising results in predicting interactions for unseen drug combinations [7].

The following diagram visualizes the typical workflow for such an AI-driven synergy prediction pipeline, from data integration to model output.

Comparative Clinical Outcomes: Combination Therapy vs. Monotherapy

The ultimate test of drug interaction principles is in clinical outcomes. Data from retrospective and controlled studies across various diseases provide evidence for the real-world impact of combination therapy.

Table 1: Comparative Clinical Outcomes in Pediatric Crohn's Disease

| Therapy Regimen | Endoscopic Healing Rate (1 year) | Antibody-to-IFX (ATI) Positivity | Durability of Treatment (5-year) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infliximab + Azathioprine (Combination) | 78.6% [6] | 25.0% [6] | 26.2% [6] | Superior endoscopic healing, higher drug trough levels, and significantly prolonged treatment durability. |

| Infliximab (Monotherapy) | 33.3% [6] | 52.2% [6] | 20.3% [6] | Higher immunogenicity (ATI formation) leading to lower drug levels and reduced treatment durability. |

Table 2: Comparative Outcomes in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer and CNS Infections

| Disease Context | Therapy Regimen | Key Efficacy Metric | Key Safety Finding | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer (Older Patients) | Gemcitabine + Cisplatin (Combination) | Median OS: 16.4 months [8] | Grade ≥3 AEs: 79% [8] | Combination therapy showed a trend toward longer survival, but with significantly increased toxicity. |

| Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer (Older Patients) | Gemcitabine (Monotherapy) | Median OS: 12.8 months [8] | Grade ≥3 AEs: 53% [8] | Monotherapy may be preferable for older, frail patients due to better safety profile. |

| Post-Neurosurgical CNS Infections | Vancomycin-based Combination Therapy (VCT) | Clinical Cure Rate: 90% [9] | N/A | VCT was significantly more effective than monotherapy, especially for complex infections. |

| Post-Neurosurgical CNS Infections | Single-Drug Therapy (SDT) | Clinical Cure Rate: 76% [9] | N/A | While effective in some cases, SDT was inferior to VCT for more complex infections. |

The mechanistic foundations of drug interactions provide a critical framework for advancing modern therapeutics. The quantitative definitions of additivity, synergism, and antagonism, anchored by models like Loewe additivity and Bliss independence, allow for the rigorous preclinical assessment of drug combinations. These principles are successfully translated into clinical practice, as evidenced by the superior endoscopic healing and treatment durability of infliximab-azathioprine combination therapy in pediatric Crohn's disease and the enhanced cure rates of vancomycin-based combinations for complex CNS infections.

The field is being transformed by the integration of computational approaches. AI and multi-omics data are powerful tools for predicting synergistic pairs, navigating the vast combinatorial space, and uncovering the biological mechanisms underlying favorable drug interactions. As these technologies mature, the design of combination therapies will become more rational and efficient, ultimately leading to improved clinical outcomes across a spectrum of diseases. Future work must focus on refining these models, validating predictions in diverse clinical settings, and establishing guidelines for the safe and effective co-administration of drugs to fully realize the potential of combination therapy.

Combination therapy, the use of two or more therapeutic agents to treat a disease, has become a cornerstone of modern clinical practice, particularly for complex, multifactorial conditions. This approach leverages complementary mechanisms of action to enhance efficacy, overcome drug resistance, and improve patient outcomes. The global combination therapy drug market, valued at $12.56 billion in 2025, is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.05% through 2033, reaching $22.31 billion, reflecting its expanding role in healthcare [10]. This growth is fueled by advancements in pharmaceutical research, increasing prevalence of chronic diseases, and a growing emphasis on personalized medicine.

The fundamental thesis guiding combination therapy development posits that strategically designed multi-drug regimens can achieve therapeutic outcomes superior to monotherapy by simultaneously targeting multiple disease pathways. This review examines the current prevalence, clinical applications, and experimental methodologies supporting combination therapy across diverse medical specialties, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive evidence base for therapeutic decision-making.

Prevalence of Combination Therapy Across Disease States

Combination therapy has become established practice across numerous therapeutic areas, with adoption rates varying by disease severity, complexity, and available treatment options.

Table 1: Prevalence of Combination Therapy Across Medical Specialties

| Therapeutic Area | Disease Condition | Prevalence of Combination Therapy | Key Factors Influencing Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology | Hypertension (Stage 2+) | 67.9% | Disease severity, BP control requirements [11] |

| Oncology | Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer | 63.7% (first-line) | Patient age, performance status [8] |

| Gastroenterology | Pediatric Crohn's Disease | 78.7% | Treatment durability, antibody prevention [6] |

| Infectious Diseases | CNS Infections (Neurosurgery) | 36.3% (VCT specifically) | Infection complexity, antibiotic resistance [9] |

| Endocrinology | MASLD with T2D | Increasing (exact % not specified) | Comorbid conditions, synergistic mechanisms [12] |

In hypertension management, a large-scale study of 305,624 patients in China demonstrated that approximately 67.9% of patients with stage 2 and above hypertension received combination therapy. From 2019 to 2021, combination therapy rates increased from 58.8% to 64.1%, with single-pill combinations rising from 25.9% to 31.0% and free combinations from 31.9% to 32.6% [11]. This trend reflects clinical recognition that most patients require multiple agents to achieve blood pressure targets.

In oncology, treatment patterns are more nuanced. For advanced biliary tract cancer in patients aged ≥75 years, combination therapy constituted 63.7% of first-line treatments, while monotherapy accounted for 36.3% [8]. The choice between approaches depends heavily on patient-specific factors, with combination therapy favored for fitter patients and monotherapy reserved for those with poorer performance status or significant comorbidities.

Comparative Clinical Outcomes: Combination Therapy vs. Monotherapy

Efficacy Endpoints Across Therapeutic Areas

Randomized controlled trials and observational studies across diverse medical conditions consistently demonstrate the superior efficacy of combination regimens compared to monotherapy for appropriate patient populations.

Table 2: Clinical Outcomes Comparison: Combination Therapy vs. Monotherapy

| Disease Condition | Therapy Comparison | Primary Endpoint | Outcome Results | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric Crohn's Disease | IFX + AZA vs. IFX monotherapy | Endoscopic Healing (1 year) | 78.6% vs. 33.3% | p < 0.001 [6] |

| Advanced BTC (≥75 years) | Combination vs. Monotherapy | Median Overall Survival | 16.4 vs. 12.8 months | HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.47-1.01 [8] |

| Postoperative CNSIs | VCT vs. SDT | Clinical Cure Rate | 90% vs. 76% | p = 0.007 [9] |

| MASLD with T2D | GLP-1RA + SGLT2i vs. SGLT2i | Composite Outcome Risk | Lower risk with combination | HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.84-0.91 [12] |

| Pediatric Crohn's Disease | IFX + AZA vs. IFX monotherapy | IFX Durability (5-year) | 26.2% vs. 20.3% | p = 0.0026 [6] |

Safety and Tolerability Considerations

While combination therapy often demonstrates superior efficacy, this benefit must be balanced against potential increases in adverse events. In advanced biliary tract cancer patients ≥75 years, grade ≥3 adverse events occurred significantly more frequently with combination therapy than monotherapy (79% vs. 53%, p = 0.001) [8]. However, treatment discontinuation rates were similar (approximately 10% in both groups), suggesting that toxicities are manageable with appropriate patient selection and monitoring.

The infliximab and azathioprine combination in pediatric Crohn's disease demonstrated a favorable risk-benefit profile, with significantly lower antibody-to-infliximab formation (25.0% vs. 52.2%, p = 0.025) and higher drug trough levels (4.6 µg/mL vs. 3.9 µg/mL, p = 0.016) compared to monotherapy [6]. This pharmacokinetic advantage contributes to both improved efficacy and treatment durability.

Methodological Frameworks for Evaluating Combination Therapies

Statistical Approaches for Preclinical Evaluation

Robust statistical methodologies are essential for accurately quantifying drug interaction effects. SynergyLMM represents a comprehensive modeling framework specifically designed for evaluating drug combination effects in preclinical in vivo studies. This linear mixed model-based approach accommodates complex experimental designs, including multi-drug combinations, and provides longitudinal analysis of both synergy and antagonism [13].

The SynergyLMM workflow encompasses five critical stages: (1) input data preparation with tumor burden measurements across treatment groups; (2) model fitting using exponential or Gompertz tumor growth kinetics with mixed effects; (3) statistical diagnostics for model validation; (4) time-resolved synergy scoring with uncertainty quantification; and (5) power analysis for experimental optimization [13]. This methodology addresses limitations of earlier approaches that failed to account for inter-animal heterogeneity and longitudinal data structure.

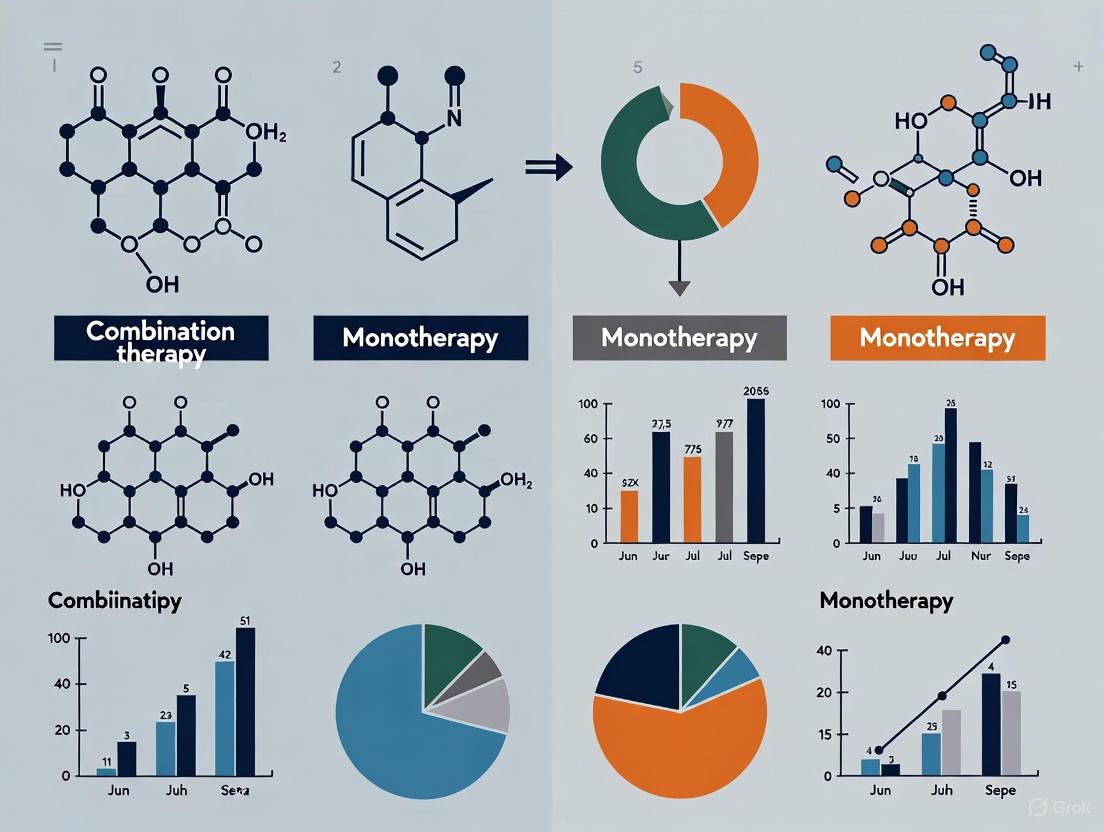

Diagram 1: SynergyLMM Workflow for In Vivo Drug Combination Analysis

Clinical Trial Designs for Combination Therapy Development

Clinical development of combination therapies requires specialized trial designs to establish the contribution of each component and detect potential interactions. Phase 2 trials often employ a 2-by-2 factorial design comparing each drug individually against placebo and the drug combination [14]. This approach enables simultaneous evaluation of individual drug effects and their interactive benefits.

For diseases like Alzheimer's, where combination therapies may target multiple pathological processes (amyloid, tau, inflammation), Phase 3 trials typically compare the novel combination to standard of care, with more complex designs required for multi-component interventions [14]. These trials increasingly incorporate biomarker-stratified populations to identify patient subgroups most likely to benefit from specific drug combinations.

The expanding complexity of combination therapy development has spurred creation of specialized databases and computational tools to support evidence-based decision making.

Table 3: Key Research Resources for Combination Therapy Development

| Resource Name | Resource Type | Primary Function | Key Features | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OncoDrug+ | Database | Precision combinatorial therapy matching | Biomarker-cancer type combination matching, evidence scoring | FDA databases, clinical guidelines, trials, PDX models [15] |

| SynergyLMM | Statistical Framework/Web Tool | In vivo combination experiment analysis | Longitudinal interaction analysis, power calculation, model diagnostics | Experimental tumor growth data [13] |

| REFLECT | Bioinformatics Algorithm | Drug combination prediction | Multi-omics co-alteration analysis, patient stratification | Genomic data, drug-target databases [15] |

| DrugCombDB | Database | Drug combination screening data | Synergy scoring integration, cell line screening data | High-throughput screening datasets [15] |

OncoDrug+ represents a significant advancement over previous databases by systematically integrating drug combination response data with biomarker and cancer type information. The platform includes 7,895 data entries covering 77 cancer types, 2,201 unique drug combination therapies, 1,200 biomarkers, and 763 published reports [15]. Each entry is prioritized using evidence scores based on FDA approval status, evidence type, biomarker reliability, and clinical outcomes.

Experimental Models for Combination Therapy Screening

Preclinical evaluation of drug combinations utilizes increasingly sophisticated model systems:

- In vitro cell line models: High-throughput screening platforms like ALMANAC and AZ-DREAM provide unbiased identification of synergistic drug combinations across characterized cancer cell lines [15].

- Patient-derived xenografts (PDXs): These models better capture tumor heterogeneity and mimic clinical treatment responses, bridging the gap between cell line models and human trials [13].

- Animal models: In vivo models, particularly mouse models, remain essential for evaluating combination therapy safety and efficacy in complex physiological environments [13].

Diagram 2: Combination Therapy Development Pipeline

Future Directions and Clinical Implementation Challenges

Despite considerable progress, several challenges remain in the optimal implementation of combination therapies. The high cost of drug development and commercialization, complex regulatory requirements, and limited reimbursement for combination approaches in some markets present significant barriers [16]. Additionally, the lack of standardized community-wide methods for quantifying synergy in preclinical studies continues to hamper consistency between combination studies [13].

Emerging trends likely to shape future combination therapy development include increased adoption of personalized medicine approaches, leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning to identify novel drug combinations, and the growth of targeted therapies tailored to specific patient populations [16]. Furthermore, the development of comprehensive databases like OncoDrug+ that integrate genetic evidence, pharmacological targets, and clinical response data will facilitate more evidence-based application of cancer drug combinations [15].

As the field advances, the successful implementation of combination therapies will increasingly depend on multidisciplinary approaches integrating computational prediction, robust preclinical models, and innovative clinical trial designs tailored to evaluate multi-component therapeutic strategies.

The choice between combination therapy and monotherapy represents a critical decision point in the treatment of complex diseases. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these therapeutic strategies across oncology, infectious diseases, and autoimmune conditions, contextualized within contemporary clinical research. As precision medicine advances, understanding the nuanced efficacy, appropriate applications, and limitations of each approach becomes essential for optimizing patient outcomes.

Oncology: Targeted Drug Combinations

Clinical Outcomes in Renal Cell Carcinoma

Recent phase II trial data (LenCabo) presented at ESMO 2025 provides direct comparison of two combination regimens for metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) following immunotherapy progression.

Table 1: Efficacy Outcomes in Second-line RCC Treatment (LenCabo Phase II Trial) [17]

| Treatment Regimen | Median Progression-Free Survival | Disease Progression Rate | Patient Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lenvatinib + Everolimus | 15.7 months | 62.5% | Metastatic ccRCC post-immunotherapy |

| Cabozantinib (monotherapy) | 10.2 months | 76% | Metastatic ccRCC post-immunotherapy |

Experimental Protocol: LenCabo Trial

- Study Design: Randomized Phase II trial comparing two second-line treatment regimens [17]

- Population: 90 patients with metastatic or advanced ccRCC who had previously received one or two treatments, including at least one immunotherapy targeting PD-1 or PD-L1 [17]

- Interventions: Experimental arm received lenvatinib plus everolimus; control arm received cabozantinib [17]

- Primary Endpoint: Progression-free survival (PFS) [17]

- Statistical Analysis: Comparative analysis of PFS between treatment arms with median follow-up duration [17]

Infectious Diseases: Combating Antimicrobial Resistance

Clinical Outcomes in Resistant Infections

Meta-analysis evidence demonstrates varied efficacy of combination therapy based on pathogen type and infection site.

Table 2: Combination Therapy Efficacy for Resistant Infections [18] [9]

| Infection Type | Therapy Comparison | Mortality Outcome (OR, 95% CI) | Clinical Success (OR, 95% CI) | Microbiological Eradication (OR, 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria (CRGNB) | Combination vs Monotherapy | 0.78 (0.66-0.90) | 1.35 (1.02-1.79) | 1.41 (1.10-1.82) |

| Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) | Combination vs Monotherapy | 0.67 (0.51-0.87) | 1.75 (0.86-3.57) | 2.08 (1.10-3.94) |

| Carbapenem-Resistant A. baumannii (CRAB) | Combination vs Monotherapy | 0.87 (0.68-1.11) | 1.05 (0.81-1.37) | 1.28 (0.89-1.85) |

| Post-Neurosurgical CNS Infections | Vancomycin Combination vs Monotherapy | N/A | 3.61 (1.61-8.81)* | N/A |

*Odds ratio for clinical cure rate [9]

Experimental Protocol: Antimicrobial Resistance Meta-Analysis

- Search Strategy: Systematic search of PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Embase through June 15, 2024 [18]

- Inclusion Criteria: Studies comparing monotherapy and combination therapy for CRGNB infections; at least 10 participants; mortality, clinical success, or microbiological eradication outcomes [18]

- Data Extraction: Independent extraction by two reviewers using standardized forms [18]

- Quality Assessment: Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool for RCTs; MINORS criteria for non-randomized studies [18]

- Statistical Analysis: Pooled odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals using random-effects models; heterogeneity assessment with I² statistic [18]

Autoimmune Diseases: Cellular Therapy Innovations

Clinical Outcomes in Refractory Autoimmune Conditions

Emerging cellular therapies demonstrate paradigm-shifting outcomes for treatment-resistant autoimmune diseases.

Table 3: CAR-T Therapy Outcomes in Autoimmune Diseases [19] [20]

| Condition | Therapy Target | Reported Outcomes | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | CD19 CAR-T | Durable drug-free remission; normalized complement levels; decreased anti-dsDNA titers; no disease flares during follow-up | Early Clinical Trials [20] |

| Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies | CD19 CAR-T | Drug-free remission with only mild, short-lived cytokine release syndrome | Early Clinical Trials [20] |

| Systemic Sclerosis | CD19 CAR-T | Significant improvement in heart, joint, and skin manifestations | Early Clinical Trials [20] |

| Multiple Autoimmune Conditions | Dual-targeting (CD19/BCMA) CAR-T | Reset immune responses; improved muscle function; reduced disability | Preclinical/Early Clinical [19] [20] |

Experimental Protocol: CAR-T Cell Therapy for Autoimmunity

- Cell Engineering: Autologous T cells genetically modified to express chimeric antigen receptors targeting B-cell markers (CD19, BCMA) [20]

- Lymphodepletion: Patients typically receive cyclophosphamide and fludarabine preconditioning [20]

- Dosing: Single infusion of CAR-T cells at varying doses based on trial protocols [20]

- Monitoring: Assessment of B-cell depletion, cytokine levels, autoantibody titers, and disease-specific activity indices [20]

- Safety Assessment: Monitoring for cytokine release syndrome (CRS), immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), and infectious complications [20]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Combination Therapy Studies [17] [18] [9]

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Targeted Therapy Inhibitors | Lenvatinib, Everolimus, Cabozantinib | Kinase inhibition studies in oncology models [17] |

| Antimicrobial Agents | Vancomycin, Meropenem, Ceftazidime | MIC determination and combination synergy testing [18] [9] |

| Cell Culture Media | RPMI-1640, DMEM, X-VIVO 15 | CAR-T cell expansion and functionality assays [20] |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Anti-CD19, Anti-BCMA, Anti-CD3 | Immune cell phenotyping and CAR expression validation [19] [20] |

| Cytokine Detection Assays | ELISA, Luminex, ELISpot | Cytokine release profiling and CRS monitoring [20] |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Lentiviral vectors, Transfection reagents, PCR kits | CAR construct delivery and validation [20] |

Regulatory Considerations in Combination Therapy Development

The FDA recently issued draft guidance (July 2025) addressing the development of novel cancer drug combinations, focusing on demonstrating the "contribution of effect" of each component drug [21]. This framework emphasizes three key scenarios:

- Two or more investigational drugs without prior FDA approval

- An investigational drug combined with a drug approved for a different indication

- Two or more drugs approved for different indications [21]

The guidance recommends approaches for establishing how each drug contributes to the overall treatment benefit, moving beyond traditional "add-on" trial designs toward more rigorous demonstration of individual component efficacy [21].

The evidence across therapeutic domains demonstrates that combination therapies frequently offer superior efficacy compared to monotherapy approaches, particularly in treatment-resistant or advanced disease states. In oncology, targeted combination regimens yield significantly improved progression-free survival. For resistant infections, combination therapy demonstrates clear mortality benefits for Gram-negative pathogens, while autoimmune diseases show promising durable remissions with cellular therapy combinations.

However, the optimal therapeutic approach remains context-dependent, requiring consideration of specific disease mechanisms, pathogen profiles, resistance patterns, and patient-specific factors. Future research directions include refining patient selection criteria, optimizing combination sequences and timing, developing predictive biomarkers for response, and addressing unique safety considerations of novel combination regimens.

The choice between monotherapy and combination therapy represents a fundamental strategic decision in clinical drug development and therapeutic practice. This comparison guide provides a systematic, evidence-based analysis of the performance of these two treatment approaches across diverse medical fields, including infectious diseases, oncology, and neurocritical care. The clinical outcomes spectrum ranges from dramatic successes with combination regimens to neutral outcomes where multi-drug interventions offer no clear advantage over single agents. This analysis is framed within the broader thesis of comparing clinical outcomes between combination and monotherapy research, examining the underlying mechanisms, methodological considerations, and contextual factors that determine therapeutic success. The evaluation is particularly relevant for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who must navigate the complex risk-benefit calculus of treatment intensification versus simplification, especially in the era of precision medicine and growing antimicrobial resistance.

Quantitative Outcomes Across Therapeutic Areas

Table 1: Clinical Efficacy Outcomes of Combination Therapy Versus Monotherapy

| Therapeutic Area | Clinical Context | Mortality OR/HR (95% CI) | Clinical Success OR/HR (95% CI) | Microbiological Eradication OR/HR (95% CI) | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious Diseases | Carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria | 1.29 (1.11-1.51)* | 0.74 (0.56-0.98) | 0.71 (0.55-0.91) | [18] |

| Infectious Diseases | CRE infections | 1.50 (1.15-1.95) | 0.57 (0.28-1.16) | 0.48 (0.25-0.91) | [18] |

| Infectious Diseases | CRAB infections | 1.15 (0.90-1.47) | 0.95 (0.74-1.24) | 0.78 (0.54-1.12) | [18] |

| Infectious Diseases | Post-neurosurgical CNS infections | 3.61 (1.61-8.81) | 90% vs 76% cure rate | N/R | [22] |

| Oncology | Advanced BTC (≥75 years) | 0.69 (0.47-1.01) | 16.4 vs 12.8 months OS | N/R | [8] |

| Oncology | Advanced GC (anti-PD-1 based) | N/R | 11.10 months mOS (total population) | N/R | [23] |

Note: OR >1 favors combination therapy for mortality; OR <1 favors combination therapy for clinical success and microbiological eradication; *Monotherapy associated with higher mortality (OR presented for monotherapy vs combination); *VCT associated with higher clinical cure (OR presented for VCT vs SDT); CRE: Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae; CRAB: Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii; BTC: Biliary tract cancer; GC: Gastric cancer; OS: Overall survival; mOS: median Overall Survival; N/R: Not reported*

Table 2: Safety and Toxicity Profiles of Combination Therapy Versus Monotherapy

| Therapeutic Area | Clinical Context | Grade ≥3 Adverse Events | Treatment Discontinuation | Specific Safety Concerns | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious Diseases | Post-neurosurgical CNS infections | N/R | N/R | No significant difference in nephrotoxicity | [22] |

| Oncology | Advanced BTC (≥75 years) | 79% vs 53% | ~10% both groups | Manageable toxicities in older patients | [8] |

| Oncology | Advanced GC (anti-PD-1 based) | 20.0% vs 10.5% | N/R | Pneumonitis (3 patients) | [23] |

| Oncology | ICI in preexisting autoimmune diseases | Higher any-grade irAEs (sHR 2.27, 1.35-3.82) | More likely to discontinue or hold ICI | No difference in high-grade irAEs or autoimmune flares | [24] |

Note: ICI: Immune checkpoint inhibitors; irAEs: Immune-related adverse events; sHR: subdistribution Hazard Ratio; N/R: Not reported

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Infectious Diseases: Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria Protocol

Study Design: The systematic review and meta-analysis included 62 studies with 8,342 participants (7 randomized controlled trials and 55 non-randomized studies) conducted up to June 15, 2024 [18].

Population: Participants aged ≥16 years with confirmed carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections rather than colonization. Carbapenem resistance was defined as non-susceptibility to any carbapenem antibiotics (ertapenem, meropenem, imipenem, doripenem) using disc diffusion or broth/agar dilution minimum inhibitory concentration tests [18].

Interventions: Monotherapy defined as administration of a single antibiotic agent. Combination therapy involved use of two or more antibiotic agents, including both standardized and non-standardized regimens. Exclusions included topical antibiotics and monotherapy with sulbactam/relebactam [18].

Outcome Measures: Primary outcome was all-cause or infection-related mortality. Secondary outcomes included clinical success (symptom resolution leading to medication discontinuation) and microbiological eradication at end of treatment [18].

Statistical Analysis: Pooled odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals calculated using random-effects models. Heterogeneity assessed using χ² test and I² statistic. Subgroup analyses performed for specific pathogens including carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii [18].

Neurocritical Care: Post-Neurosurgical CNS Infections Protocol

Study Design: Retrospective cohort study conducted between January 2019 and December 2023, aligning with STROBE guidelines [22].

Population: 539 patients with confirmed postoperative central nervous system infections following neurosurgical procedures. Inclusion required meeting expert consensus diagnostic criteria for NCNSI and age ≥18 years. Exclusions included brain abscesses, severe hepatic/renal dysfunction, and confirmed infections at other body sites [22].

Interventions: Single-drug therapy versus vancomycin-based combination therapy. Antimicrobial agents followed established guidelines: vancomycin 1g q12h, meropenem 2g q8h, ceftazidime 2g q8h, ceftriaxone 2g q12h [22].

Outcome Measures: Primary outcome was effectiveness of initial empirical antibacterial treatment, classified as effective (critical improvement in infection symptoms leading to medication discontinuation) or ineffective (absence of improvement, worsening symptoms, or need to switch agents after standard assessment duration) [22].

Statistical Analysis: Propensity score matching with 1:2 ratio adjusting for length of stay, admission status, age, Charlson Comorbidity Index, surgical complexity, and duration of surgery. Logistic regression performed for dual robustness [22].

Oncology: Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer Protocol

Study Design: Retrospective study of 157 patients with unresectable or recurrent BTC aged ≥75 years treated between August 2011 and November 2020 [8].

Population: Patients aged ≥75 years with histologically or cytologically confirmed BTC, including gallbladder cancer, intrahepatic bile duct cancer, extrahepatic bile duct cancer, or ampulla of Vater cancer [8].

Interventions: Combination therapy (gemcitabine + cisplatin or gemcitabine + S-1) versus monotherapy (gemcitabine or S-1 alone). Dosing followed standard protocols with adjustments for body surface area where applicable [8].

Assessment Schedule: Computed tomography with contrast performed every 6-8 weeks. Radiological response assessed per RECIST v1.1. Treatment continued until disease progression, intolerable adverse events, or patient refusal [8].

Outcome Measures: Overall survival (time from treatment initiation to death from any cause), progression-free survival (time to progression or death), adverse events (NCI CTCAE v5.0), and dose intensity [8].

Signaling Pathways and Mechanism of Action

Diagram 1: Immuno-Oncology Combination Therapy Mechanisms illustrating synergistic pathways of PD-1/CTLA-4/LAG-3 inhibition in cancer immunotherapy.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Model Systems for Combination Therapy Studies

| Research Tool | Application Context | Function and Utility | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c-hPD1/hPDL1/hCTLA4 tri-genetic humanized mouse | Immuno-oncology combination studies | Recapitulates human immune checkpoint interactions; enables evaluation of PD-1/CTLA-4 inhibitor combinations | CT26-hPDL1 colorectal cancer model [25] |

| B6-hPD1/hLAG3 dual-genetic humanized mouse | Immuno-oncology combination studies | Models PD-1/LAG-3 synergistic inhibition; assesses T-cell exhaustion reversal | B16F10 melanoma model [25] |

| B6-hPD1 humanized mouse | Immuno-oncology combination studies | Evaluates PD-1 inhibitors with chemotherapy, ADC, or other modalities | MC38-hPDL1 colorectal cancer model [25] |

| Antimicrobial susceptibility testing systems | Infectious diseases combination studies | Determines MIC values and synergy testing for antibiotic combinations | Disc diffusion, broth/agar dilution MIC tests [18] |

| Propensity score matching methodologies | Observational study analysis | Adjusts for confounding variables in retrospective combination therapy studies | 1:2 PSM for neurosurgical CNS infections [22] |

| RECIST v1.1 criteria | Oncology therapeutic response | Standardizes radiological response assessment in solid tumors | Advanced BTC and GC studies [8] [23] |

Discussion: Interpretation of Heterogeneous Outcomes

The evidence presented demonstrates that the efficacy of combination therapy versus monotherapy is highly context-dependent, with several key determinants influencing therapeutic success:

Pathogen- and Mechanism-Specific Factors: In infectious diseases, the superiority of combination therapy for carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria was primarily driven by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections, where monotherapy was associated with significantly higher mortality and lower microbiological eradication. In contrast, for carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections, no significant differences were observed between approaches [18]. This pathogen-specific effect underscores the importance of microbial taxonomy and resistance mechanisms in therapeutic decisions.

Patient Population Considerations: Across therapeutic areas, patient characteristics significantly influenced the relative benefit of combination approaches. In older patients (≥75 years) with advanced biliary tract cancer, combination therapy showed only a non-significant trend toward improved overall survival despite significantly higher toxicity rates [8]. Similarly, in gastric cancer patients treated with anti-PD-1 therapies, combination approaches showed enhanced efficacy in specific subgroups including those with liver metastases or elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios, while monotherapy remained preferable for elderly patients or those with higher ECOG performance scores [23].

Therapeutic Synergy Mechanisms: The superior outcomes with certain combination regimens can be explained by synergistic biological mechanisms. In immuno-oncology, PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors target complementary pathways—PD-1 primarily affects the effector phase of immune response in peripheral tissues, while CTLA-4 modulates early T-cell activation in lymphoid organs [25]. This mechanistic complementarity creates synergistic anti-tumor effects that exceed monotherapy benefits.

Risk-Benefit Calculus: The combination therapy decision requires careful weighing of enhanced efficacy against increased toxicity. While vancomycin-based combination therapy demonstrated significantly higher clinical cure rates for post-neurosurgical CNS infections, this must be balanced against potential nephrotoxicity concerns [22]. Similarly, in patients with preexisting autoimmune diseases receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors, combination therapy increased any-grade immune-related adverse events but did not significantly increase high-grade toxicities or autoimmune flares [24].

The clinical evidence spectrum comparing combination therapy with monotherapy reveals a complex risk-benefit profile that varies substantially across therapeutic areas, patient populations, and specific agent combinations. Dramatic successes emerge in contexts where combination approaches target complementary resistance mechanisms or synergistic biological pathways, particularly in multidrug-resistant infections and specific cancer subtypes. Neutral outcomes frequently occur when therapeutic contexts lack these synergistic mechanisms or when patient factors limit tolerance of combination regimens.

Future research should prioritize the development of predictive biomarkers that can identify patient subgroups most likely to benefit from combination approaches, thereby maximizing efficacy while minimizing unnecessary toxicity. Adaptive trial designs that efficiently evaluate both monotherapy and combination therapy within unified frameworks represent a promising methodological advancement [26]. Additionally, expanded use of humanized animal models that recapitulate human immune and therapeutic responses will enhance preclinical evaluation of combination regimens [25].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, these findings underscore the importance of context-specific therapeutic decisions rather than universal preferences for either monotherapy or combination approaches. The continuing evolution of precision medicine and biomarker-driven therapy selection will further refine these paradigms, enabling more targeted and effective application of both therapeutic strategies across diverse clinical contexts.

Clinical Trial Designs and Analytical Frameworks for Evaluating Combination Regimens

The evaluation of combination therapies versus monotherapy presents a fundamental challenge in clinical research. For conditions where a single drug yields an insufficient therapeutic response, using two or more drugs has become a common strategy across multiple medical domains, including hypertension, heart failure, asthma, oncology, and functional urology [27]. The central thesis in this field contends that meaningful combination treatment should demonstrate superior clinical outcomes over monotherapy while maintaining acceptable safety profiles. However, the methodological approach researchers select to test these combinations—whether parallel group or add-on designs—profoundly influences the validity, interpretation, and clinical applicability of the findings.

This comparison guide objectively examines these two predominant study design frameworks, detailing their experimental protocols, analytical considerations, and appropriate contexts of use. For drug development professionals and clinical researchers, understanding these distinctions is critical for designing trials that yield clinically interpretable results about the true benefit/risk ratio of combination treatment over monotherapy at both the group and individual patient levels [27].

Core Design Frameworks: A Comparative Analysis

The parallel group and add-on approaches represent fundamentally different methodologies for evaluating treatment combinations, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and appropriate applications.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Parallel Group and Add-On Study Designs

| Design Aspect | Parallel Group Design | Add-On Design |

|---|---|---|

| Group Allocation | Simultaneous randomization to monotherapy A, monotherapy B, or combination AB | Initial treatment with monotherapy A, followed by randomization of non-responders to add therapy B or placebo |

| Patient Population | Broad, including responders and non-responders to monotherapy | Targeted, focusing specifically on demonstrated non-responders to initial monotherapy |

| Control Mechanism | Concurrent controls across all treatment arms | Within-subject control with sequential treatment phases |

| Primary Strength | Assesses long-term outcomes and natural disease progression; avoids ethical concerns of delaying effective treatment | Identifies true drug synergy in refractory populations; reduces unnecessary drug exposure |

| Primary Limitation | May overestimate combination benefit by including patients who respond to single agents | Vulnerable to sequence effects and placebo responses during add-on phase |

| Optimal Application | Conditions requiring long-term outcome data (e.g., mortality, disease progression) | Conditions where monotherapy failure can be rapidly identified |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Parallel Group Design Protocol

The parallel group approach represents the most straightforward methodological framework for comparing combination therapy against monotherapies:

Randomization Phase: Eligible participants are randomly assigned to one of three or more parallel arms: monotherapy A, monotherapy B, or combination AB. Some designs may include a placebo control arm if ethically justifiable [27].

Treatment Initiation: All treatments begin simultaneously across all study arms, with careful attention to blinding procedures when possible.

Outcome Assessment: Researchers measure primary and secondary endpoints at predefined intervals across all groups concurrently. The study duration must be sufficient to capture the full therapeutic effect of all interventions, which is particularly important when combination partners have different times to onset of action [27].

Statistical Analysis: The primary analysis compares outcomes between the combination arm and each monotherapy arm, typically using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for continuous outcomes or logistic regression for binary outcomes, adjusting for baseline characteristics.

This design was implemented in studies comparing α1-adrenoceptor antagonists, 5α-reductase inhibitors, and their combination for male lower urinary tract symptoms, where it helped establish the long-term (≥2 years) superiority of combination treatment over either monotherapy [27].

Add-On Design Protocol

The add-on design employs a sequential approach to identify true combination benefits in refractory populations:

Run-In Phase: All enrolled participants receive monotherapy A for a predetermined period sufficient to establish therapeutic response.

Response Assessment: Researchers evaluate treatment response using predefined criteria. Participants meeting criteria for insufficient response proceed to randomization.

Randomization Phase: Qualified non-responders are randomly assigned to either add active drug B or add a matching placebo to their ongoing monotherapy A in a double-blind manner [27].

Outcome Assessment: The primary endpoint compares the add-on active group versus the add-on placebo group after a second treatment period, focusing on change from pre-randomization baseline.

A gold-standard implementation of this approach randomized men with lower urinary tract symptoms who showed insufficient improvement with α1-adrenoceptor antagonist tamsulosin to additionally receive the muscarinic receptor antagonist tolterodine or not [27]. Variations of this design may include multiple doses of the add-on drug or compare the add-on approach against dose escalation of the initial monotherapy [27].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Outcomes Across Designs

Table 2: Representative Efficacy Outcomes from Different Study Designs

| Therapeutic Area & Intervention | Study Design | Monotherapy Response | Combination Response | Outcome Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric/GE Junction Cancer (ASP2138) | Add-on to standard chemo | Not applicable | 68% (1st line with FOLFOX + pembrolizumab) | Objective Response Rate [28] |

| Gastric/GE Junction Cancer (ASP2138) | Add-on to 2nd line therapy | Not applicable | 38% (2nd line with paclitaxel + ramucirumab) | Objective Response Rate [28] |

| R/R Acute Leukemia (Bleximenib monotherapy) | Parallel group (dose escalation) | Not applicable | 55% (150 mg BID dose) | Overall Response Rate [29] |

| R/R KMT2Ar Acute Leukemia (Revumenib) | Parallel group | Not applicable | 64% | Overall Response Rate [29] |

Analytical Considerations and Interpretation Challenges

Critical Analytical Concepts

The interpretation of combination therapy trials requires careful attention to several methodological challenges:

Baseline Equivalence Testing: In parallel group designs, testing for baseline group equivalence is a statistically flawed practice that persists despite widespread criticism in the literature [30]. Such tests have low power to detect meaningful differences, especially in small samples, and their results do not guarantee that groups are equivalent on unmeasured prognostic factors [30].

Temporal Effect Dynamics: The benefit of combination treatment may vary over time, particularly when drugs have different times to onset. For instance, a combination of finasteride and tadalafil showed declining group differences over 26 weeks as the slower-acting 5α-reductase inhibitor reached its full effect [27]. Studies shorter than one year might miss combination benefits that only manifest with longer treatment durations [27].

Interaction Effects: The statistical and clinical interaction between treatments significantly impacts study power and design requirements. Antagonistic treatment effects may require double the sample size of synergistic effects, and 4-arm factorial designs need approximately 10-fold more participants than 2-arm combination studies [31].

Response Heterogeneity

A crucial consideration in interpreting combination therapy trials lies in understanding that benefits observed at the group level often overestimate the probability of benefit at the individual patient level [27]. Research demonstrates that only a subset of combination therapy responders are truly benefitting from the synergistic effect, while others would have responded adequately to one monotherapy alone. Equations have been proposed to calculate the percentage of patients truly benefitting from combination (responders to both monotherapies) versus those exposed to potential harm without reasonable expectation of individual benefit [27].

Visualizing Study Design Frameworks

The diagram above illustrates the fundamental structural differences between these two design approaches. The parallel group design evaluates all treatments simultaneously in distinct patient groups, while the add-on design sequentially identifies treatment-resistant patients before testing the combination effect.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Combination Therapy Studies

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ASP2138 (CLDN18.2/CD3 BiTE) | Bispecific T-cell engager targeting CLDN18.2-positive tumor cells | Gastric/GE junction adenocarcinoma studies [28] |

| CS2009 | PD-1/VEGF/CTLA-4 trispecific antibody | Immuno-oncology combination studies [32] |

| Menin Inhibitors (Revumenib, Bleximenib) | Target KMT2A-menin protein-protein interaction | Acute leukemia with KMT2A rearrangements or NPM1 mutations [29] |

| Standard Chemotherapy Backbones | Provide foundation for combination efficacy assessment | Context-specific control arms (e.g., FOLFOX, paclitaxel/ramucirumab) [28] |

| Validated Biomarker Assays | Patient stratification and response monitoring | CLDN18.2 expression testing, KMT2A rearrangement detection [28] [29] |

The choice between parallel group and add-on designs hinges on the specific research question, clinical context, and therapeutic agents under investigation. Parallel group designs offer methodological simplicity and are essential for evaluating long-term outcomes like disease progression or mortality, particularly when delaying effective treatment would be unethical [27]. Conversely, add-on designs provide a more targeted approach to identify true synergistic effects in refractory populations while limiting unnecessary drug exposure [27].

Advanced methodologies like propensity score matching and regression discontinuity analysis offer potential enhancements for addressing selection bias in non-randomized settings, though they require larger sample sizes and sophisticated analytical expertise [30]. Ultimately, researchers must carefully weigh the advantages and limitations of each design framework to select the most appropriate format for evaluating their specific combination therapy, with some development programs benefitting from incorporating multiple design types to fully characterize combination treatment effects [27].

This guide objectively compares the performance of combination therapy versus monotherapy in clinical research, focusing on the critical role of endpoint selection—including survival metrics, clinical response, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs)—in evaluating treatment efficacy.

Comparative Performance of Combination Therapy vs. Monotherapy

The choice between combination therapy and monotherapy is context-dependent, varying by disease area, patient population, and treatment target. The table below summarizes key comparative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Combination Therapy vs. Monotherapy Clinical Outcomes

| Disease Area / Condition | Intervention (Combination vs. Monotherapy) | Key Efficacy Findings (Combination vs. Monotherapy) | Key Safety & PRO Findings | Source / Trial Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR-mutant Advanced NSCLC | Osimertinib + Platinum–Pemetrexed vs. Osimertinib | - Median OS: 47.5 mo vs. 37.6 mo [33]- Median OS in CNS mets: 40.9 mo vs. 29.7 mo [33] | - Increased AEs (nausea, vomiting, fatigue, bone marrow toxicity) with combination, especially during initial platinum-based phase [33] | FLAURA2 [33] |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | Baricitinib + csDMARDs vs. Baricitinib | - No significant difference in final disease activity scores (DAS28-CRP, SDAI, CDAI) [34]- Higher proportion achieved low disease activity (SDAI/CDAI) with monotherapy [34] | - Similar overall AE rates [34]- Serious AEs slightly more common in combination therapy [34] | Single-center retrospective [34] |

| Post-neurosurgical CNS Infections | Vancomycin Combination Therapy (VCT) vs. Single-Drug Therapy (SDT) | - Clinical Cure Rate: 90% vs. 76% [35] [22] | - VCT preferred for complex infections; SDT effective for certain cases, considering antibiotic resistance [35] [22] | Retrospective cohort [35] [22] |

| Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma (aRCC) | Lenvatinib + Pembrolizumab vs. Sunitinib | - PFS HR: 0.39 [36]- OS HR: 0.79 (final analysis) [36]- Complete Response Rate: 18% [36] | - Grade 3–5 TRAEs: 82.4% with combination vs. lower with other regimens [36]- 69% required dose reductions due to AEs [36] | CLEAR [36] |

| Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria (PNH) | Pozelimab + Cemdisiran vs. Pozelimab (after transition from monotherapy) | - 83.3% maintained hemolysis control [37]- 92% transfusion-free [37] | - Majority of AEs were mild to moderate [37]- Maintained improvements in fatigue, physical function, and QoL [37] | Phase 2 trial [37] |

Methodologies for Endpoint Assessment

Assessing Survival and Clinical Response

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) are traditional efficacy endpoints. The following protocol outlines a standard methodology for their assessment in a randomized controlled trial (RCT), as exemplified by the FLAURA2 and CLEAR trials [33] [36].

Experimental Protocol 1: Survival and Radiographic Response in Oncology RCTs

- Study Design: Global, randomized, phase 3 trial.

- Patient Population: Defined by specific disease criteria (e.g., EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC for FLAURA2, untreated aRCC for CLEAR) [33] [36].

- Randomization & Blinding: Patients randomized to combination therapy or monotherapy arm. May be open-label.

- Intervention:

- Endpoint Assessment:

- Overall Survival (OS): Time from randomization to death from any cause. Analyzed at pre-specified data cutoffs after extended follow-up (e.g., median 49.8 months in CLEAR) [33] [36].

- Progression-Free Survival (PFS): Time from randomization to first radiographic disease progression or death. Tumor imaging performed at regular intervals and assessed by blinded independent central review using standardized criteria like RECIST 1.1 [36].

- Objective Response Rate (ORR): Proportion of patients with a predefined reduction in tumor burden (Complete or Partial Response) [36].

- Statistical Analysis: Hazard ratios (HRs) with confidence intervals (CIs) calculated for OS and PFS using stratified Cox regression models. Kaplan-Meier estimates used for median survival times [36].

Integrating Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs)

PROs provide direct patient insight into treatment impact. The protocol below is informed by recommendations from international consortia and their application in recent trials [38] [39] [40].

Experimental Protocol 2: PRO Integration in Clinical Trials

- Instrument Selection:

- Study Design & Timing:

- Data Collection:

- Endpoint Definition & Analysis:

- PRO-Specific Endpoints: Time to definitive deterioration in a symptom or function; mean change in score from baseline; proportion of patients achieving a predefined meaningful improvement ("responders") [39] [40].

- Statistical Analysis: Mixed models for repeated measures, Cox regression for time-to-deterioration, and descriptive statistics. Analysis of the prognostic value of baseline PROs for survival using C-statistics [40].

Visualizing Endpoint Selection and PRO Integration

The following diagrams illustrate the logical framework for endpoint selection and the workflow for integrating PROs in clinical trials.

Figure 1: A framework for selecting endpoints in clinical trials.

Figure 2: Workflow for integrating PROs in clinical trials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Instruments

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Endpoint Assessment

| Item / Tool | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| RECIST 1.1 Guidelines | Standardized framework for measuring tumor lesions and defining objective response (e.g., Complete Response, Partial Response) and progression in solid tumor clinical trials [36]. |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 Questionnaire | Validated 30-item core instrument to assess the quality of life of cancer patients. It incorporates multi-item scales for functions, symptoms, and global health status/QoL [41] [40]. |

| EORTC QLQ-LC13 Questionnaire | A supplemental lung cancer-specific module used alongside the QLQ-C30. It assesses symptoms like coughing, dyspnea, and pain specific to lung cancer and its treatment [40]. |

| Electronic PRO (ePRO) Systems | Digital platforms (e.g., tablets, web portals) for direct patient data entry. They improve data quality, real-time capture, and patient compliance with PRO questionnaires [38] [41]. |

| Cox Proportional Hazards Model | A key statistical method for survival analysis. It estimates the hazard ratio (HR), comparing the risk of an event (e.g., death, progression) between treatment arms over time [36] [40]. |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) | A method of categorizing patient comorbidities based on ICD diagnosis codes. It is used as a covariate to predict mortality and adjust for patient risk in observational studies [22]. |

Observational studies are crucial for comparing treatment outcomes, such as combination therapy versus monotherapy, in real-world clinical settings where randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are not feasible. However, the non-random assignment of treatments introduces the risk of channeling bias, a type of selection bias that occurs when drugs with similar indications are systematically prescribed to patients with varying baseline prognoses [42] [43]. This bias arises because clinicians make treatment decisions based on individual patient characteristics, disease severity, and comorbidities, leading to imbalanced comparison groups [44]. For instance, newer or more aggressive treatments like combination therapy are often "channeled" to patients with more severe disease or poorer prognostic factors [43] [44]. Consequently, any observed outcome differences may reflect these underlying patient disparities rather than true treatment effects, potentially leading to erroneous conclusions about therapeutic effectiveness or safety [43] [45].

Addressing channeling bias is particularly critical when comparing clinical outcomes of combination therapy versus monotherapy. These treatment strategies are rarely assigned randomly in real-world practice, and the factors influencing prescription decisions are often closely tied to the expected outcomes [46] [8] [6]. This article explores key statistical methods, particularly propensity score analysis, to mitigate channeling bias and confounding, enabling more valid comparisons of monotherapy and combination therapy in observational research.

Theoretical Foundations: Channeling Bias and Confounding

Defining Channeling Bias and Its Mechanisms

Channeling bias represents a systematic distortion in observational research that stems from non-random treatment assignment. It occurs when "interventions having similar indications are differentially prescribed to groups of patients at varying levels of risk or with prognostic differences" [47]. In practical terms, clinicians may channel patients with specific risk profiles toward particular treatments based on clinical characteristics not captured in typical datasets [43].

The mechanisms of channeling bias are particularly evident when comparing therapeutic approaches:

- Newer vs. Older Therapies: Newer drugs are often prescribed to patients who have failed previous treatments or who have more severe disease, potentially making the new drug appear less effective or less safe than established alternatives [43].

- Combination Therapy vs. Monotherapy: More intensive combination regimens are typically channeled to patients with higher disease severity, worse functional status, or poorer prognostic markers, while monotherapy may be reserved for milder cases [8]. For example, in a study of advanced biliary tract cancer, patients receiving monotherapy were significantly older and had worse performance status than those receiving combination therapy [8].

Distinguishing Channeling Bias from Confounding by Indication

While related, channeling bias and confounding by indication represent distinct methodological challenges:

- Confounding by indication occurs when the underlying diagnosis or clinical features that determine treatment selection are also independent risk factors for the outcome under study [47].

- Channeling bias specifically refers to the differential prescribing patterns where similar treatments are directed toward patients with different risk profiles [43] [47].

The relationship between these concepts and their impact on treatment outcomes can be visualized as follows:

Figure 1: The relationship between patient factors, treatment selection, and clinical outcomes, showing how channeling bias and confounding distort the true treatment effect.

Consequences of Unaddressed Channeling Bias

Failure to account for channeling bias can severely compromise the validity of observational study findings:

- Misattribution of Outcomes: Worse outcomes observed with combination therapy might reflect more severe underlying disease rather than true treatment effects [44].

- Incorrect Clinical Decisions: Biased results may lead to inappropriate treatment recommendations or formulary decisions [45].

- Regulatory Impact: Flawed observational studies can trigger unnecessary drug safety concerns or obscure genuine safety signals [45].

A quantitative assessment in rheumatology found that channeling bias resulted in an overall increase in measured disease severity of approximately 25% for patients starting COX-2 specific inhibitors compared to non-users [44]. This magnitude of bias could substantially alter the perceived risk-benefit profile of treatments.

Propensity Score Analysis: Primary Method for Addressing Channeling Bias

Theoretical Basis of Propensity Scores

Propensity score analysis represents a powerful statistical approach to adjust for channeling bias by simulating key aspects of randomized experimentation. The propensity score is defined as the conditional probability of a patient receiving a specific treatment (e.g., combination therapy versus monotherapy) given their observed baseline covariates [42] [43]. By creating comparison groups with similar propensity scores, researchers can approximate the balanced patient characteristics typically achieved through randomization [43].

The mathematical foundation of propensity scores relies on the assumption that if two patients have identical propensity scores, the assignment of treatment is essentially random with respect to the observed covariates. This principle enables observational studies to mimic RCT conditions by comparing outcomes between treated and untreated patients who had similar probabilities of receiving the treatment based on all measured pre-treatment characteristics [43].

Implementing Propensity Score Analysis: A Step-by-Step Protocol

Successful implementation of propensity score analysis requires meticulous attention to each step of the process:

Step 1: Propensity Score Estimation

- Fit a logistic regression model with treatment assignment (e.g., combination therapy = 1, monotherapy = 0) as the dependent variable

- Include all pre-treatment baseline characteristics potentially related to both treatment assignment and outcome as independent variables

- Consider including known clinical risk factors, demographic variables, disease severity markers, comorbidities, and healthcare utilization metrics

- Extract the predicted probabilities from this model – these represent the propensity scores [43]

Step 2: Assessing Propensity Score Quality

- Evaluate the distribution of propensity scores across treatment groups to ensure sufficient overlap

- Check that the model demonstrates adequate discrimination (e.g., via c-statistic) but avoid overfitting

- Assess covariate balance before and after propensity score application [43]

Step 3: Utilizing Propensity Scores in Analysis Several techniques are available for incorporating propensity scores into outcome analyses:

- Matching: Create matched pairs of treated and untreated patients with similar propensity scores (e.g., 1:1, 1:2, or 1:many matching) [9]

- Stratification: Group patients into strata (typically quintiles) based on propensity score distribution and analyze outcomes within strata

- Covariate Adjustment: Include the propensity score as a continuous covariate in the outcome regression model

- Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW): Weight each patient by the inverse of their probability of receiving the actual treatment [43]

Step 4: Assessing Balance After Adjustment

- Compare standardized differences for all covariates between treatment groups after applying the propensity score method

- Aim for standardized differences <10% for all key covariates to indicate adequate balance

- Visually inspect the distribution of propensity scores between groups [9]

Table 1: Comparison of Propensity Score Implementation Methods

| Method | Key Implementation | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propensity Score Matching | Matches each treated patient with one or more untreated patients with similar scores | Creates directly comparable patient pairs; intuitive interpretation | May exclude unmatched patients, reducing sample size | When sufficient overlap exists between treatment groups [9] |

| Stratification | Divides patients into 5-10 subgroups based on propensity score quantiles | Uses entire sample; straightforward implementation | Residual confounding possible within strata | With large sample sizes and good score distribution [43] |

| Covariate Adjustment | Includes propensity score as continuous covariate in outcome model | Simple to implement; preserves sample size | Assumes correct functional form of relationship | When propensity score has linear relationship with outcome [43] |

| Inverse Probability Weighting | Weights patients by inverse probability of received treatment | Creates pseudo-population with balanced covariates | Sensitive to extreme weights; less intuitive | When seeking population-average treatment effects [43] |

Case Study: Propensity Score Application in Neurosurgical Infections

A retrospective cohort study of central nervous system infections following neurosurgery demonstrated the practical application of propensity score matching to address channeling bias [9]. The researchers compared single-drug therapy (SDT) versus vancomycin combination therapy (VCT) in 539 patients, using 1:2 propensity score matching to balance important covariates including length of stay, admission status, age, comorbidity status, surgical complexity, and duration of surgery [9].

After propensity score matching, the analysis revealed a significantly higher clinical cure rate for VCT (90%) compared to SDT (76%), with an adjusted odds ratio of 3.605 (95% CI: 1.611-8.812, p=0.003) [9]. This robust association, which persisted after accounting for channeling bias through propensity score methodology, provided compelling evidence supporting combination therapy for complex neurosurgical infections.

Complementary Methods for Addressing Channeling Bias

New-User Active Comparator Design

The new-user active comparator design represents a powerful approach to complement propensity score methods in addressing channeling bias. This design incorporates two key elements:

- New-User Design: Restricts the study population to patients initiating a new treatment, avoiding prevalent users who have already "survived" the early treatment period and may represent a selected population [48] [47].

- Active Comparator: Uses patients initiating an alternative active treatment as the comparison group, rather than non-users, which helps ensure similar patient characteristics related to treatment indication [48].

This design was effectively implemented in a study comparing cardiovascular risk between testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE5is) [45]. The active comparator design helped mitigate channeling bias by comparing two active treatments with similar indications rather than comparing treated patients to untreated controls, who might differ systematically in unmeasured health factors.

Instrumental Variable Analysis

Instrumental variable (IV) analysis offers an alternative approach to address both measured and unmeasured confounding, including channeling bias. This method utilizes a variable (the instrument) that:

- Influences treatment selection but does not directly affect the outcome

- Affects the outcome only through its relationship with the assigned treatment [43]

The IV approach is particularly valuable when unmeasured confounding is suspected, as it does not require measuring all potential confounders. However, finding a valid instrument that meets these assumptions can be challenging in practice [43].

Experimental Protocols for Valid Treatment Comparisons

Standardized Protocol for Comparative Effectiveness Research

Implementing rigorous methodological standards is essential for producing valid comparisons of combination therapy versus monotherapy. The following protocol outlines key steps:

Protocol Title: Prospective Protocol for Retrospective Database Studies Comparing Combination Therapy versus Monotherapy

Primary Objective: To compare the effectiveness and safety of combination therapy versus monotherapy for [specific condition] while minimizing channeling bias and confounding.

Study Design Elements:

- Cohort Definition: Apply explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria to define the source population [9]

- Exposure Definition: Clearly define treatment initiation (index date) using prescription claims or electronic health record data [9] [45]

- Comparator Selection: Implement an active comparator new-user design where feasible [48] [45]

- Covariate Assessment: Measure all potential confounders during a predefined baseline period (typically 6-12 months before treatment initiation) [9] [45]

- Outcome Ascertainment: Define outcomes using validated algorithms based on diagnosis codes, procedures, and clinical data [9]

Analysis Plan:

- Specify propensity score methods (matching, weighting, or stratification) a priori

- Define all covariates for propensity score model based on clinical knowledge and literature review

- Plan sensitivity analyses using different methodological approaches (e.g., instrumental variable analysis)

- Specify subgroup analyses to assess effect modification [43] [9]

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methodological Components

Table 2: Essential Methodological Components for Addressing Channeling Bias

| Component | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Data Source | Provides comprehensive capture of patient characteristics, treatments, and outcomes | Assess completeness of data on confounders; consider linked electronic health records and claims data [43] |

| Propensity Score Algorithms | Statistical adjustment for measured confounders | Select appropriate method (matching, weighting, stratification) based on sample size and overlap [43] [9] |

| Active Comparator | Minimizes channeling by comparing similar treatment indications | Choose comparator with similar clinical indication but different safety/efficacy profile [45] |

| New-User Design | Reduces selection bias by focusing on treatment initiators | Define adequate washout period to establish new use; assess impact on sample size [48] |

| Sensitivity Analyses | Assess robustness of findings to different assumptions | Plan multiple propensity score approaches; consider quantitative bias analysis [43] |

Case Studies in Monotherapy versus Combination Therapy Research

Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment Comparisons