Bridging the Gap: A Comprehensive Guide to In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation of Anti-Infective Efficacy

Establishing a reliable correlation between in vitro and in vivo efficacy (IVIVC) is a critical yet challenging endeavor in anti-infective drug development.

Bridging the Gap: A Comprehensive Guide to In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation of Anti-Infective Efficacy

Abstract

Establishing a reliable correlation between in vitro and in vivo efficacy (IVIVC) is a critical yet challenging endeavor in anti-infective drug development. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles of IVIVC and the significant obstacles posed by physiological complexity and biofilm-related infections. It delves into advanced methodological approaches, including sophisticated in vitro models and PK/PD modeling, which are enhancing predictive power. The content further addresses troubleshooting common discrepancies and offers strategies for model optimization. Finally, it examines validation frameworks and comparative analyses of successful IVIVC case studies across different anti-infective classes, synthesizing key takeaways to guide future research and improve the translation of preclinical findings to clinical success.

The Core Challenge: Why Predicting In Vivo Efficacy from In Vitro Data is So Difficult

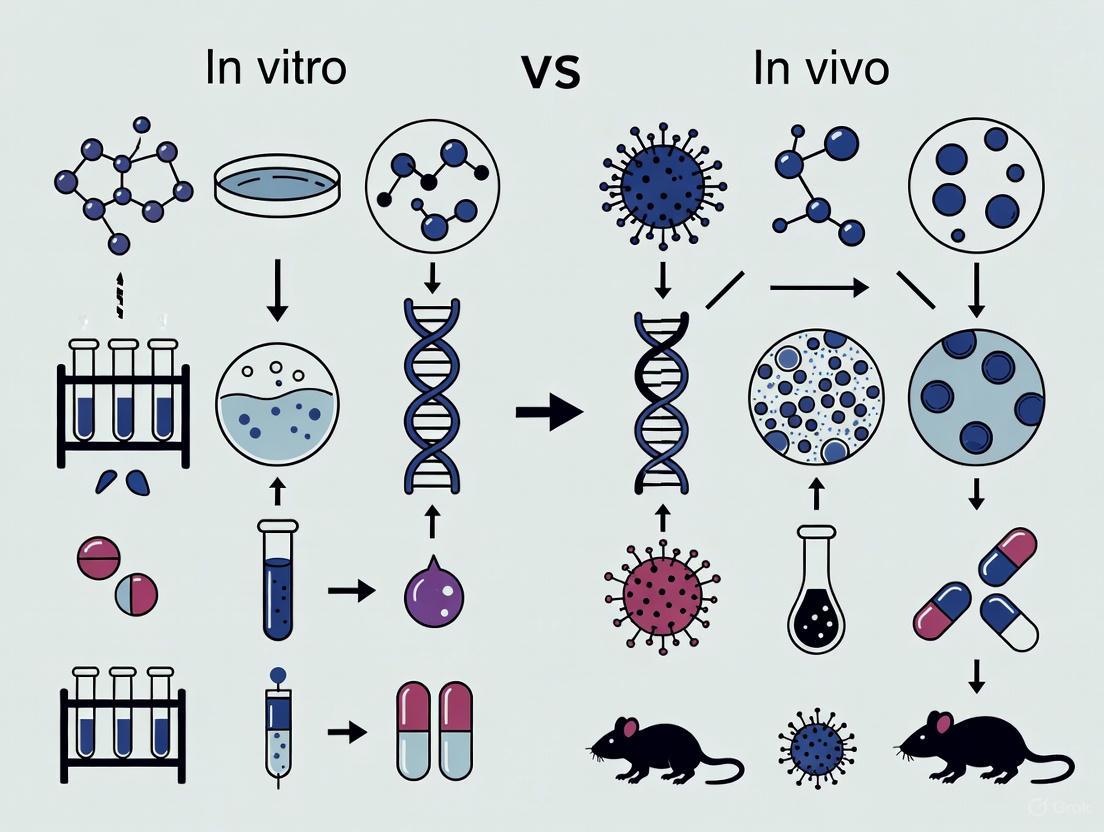

In the relentless pursuit of novel anti-infective therapies, researchers navigate a critical transition between controlled laboratory studies and the complex reality of living systems. The chasm separating in vitro (in an artificial environment) and in vivo (within a living organism) results is a pivotal focus in antimicrobial development, where promising laboratory findings often fail to translate into clinical efficacy. This guide objectively compares the performance and outcomes of anti-infective agents across these two environments, framing the analysis within the broader context of in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC). Understanding these fundamental differences is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for designing more predictive experiments, accelerating drug development, and ultimately delivering effective treatments to patients grappling with antimicrobial-resistant infections.

Fundamental Environmental Differences

The disparity between in vitro and in vivo results stems from profound differences in environmental complexity. The in vitro environment is a simplified, controlled system designed to isolate specific biological interactions. In contrast, the in vivo environment is an interconnected network of biological systems that introduces numerous variables absent in laboratory settings.

The diagram above illustrates the fundamental environmental divide. In vitro systems lack the dynamic pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) profiles present in living organisms, where drugs experience absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion [1] [2]. The absence of a functional immune system in vitro eliminates potential synergistic antimicrobial effects, as even potent peptides like Ctn[15-34] must function without immune assistance [2]. Furthermore, in vitro models typically employ single-species cultures that ignore polymicrobial interactions and biofilm communities commonly encountered in clinical infections [3]. The simplified growth media used in laboratories cannot replicate the complex composition of biological fluids, which contain proteins that bind drugs, enzymes that degrade therapeutics, and variable pH levels that alter antimicrobial activity [4] [2].

Quantitative Comparison of Anti-infective Efficacy

The environmental differences between laboratory and living systems manifest as quantifiable disparities in antimicrobial efficacy. The table below summarizes comparative data from recent studies demonstrating these gaps for various anti-infective agents.

Table 1: Comparative Efficacy of Anti-infective Agents: In Vitro vs. In Vivo Results

| Anti-infective Agent | Pathogen | In Vitro Efficacy (MIC) | In Vivo Efficacy | Key Disparity Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cefiderocol [1] | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Susceptible (MIC ≤2 µg/mL) | 1-log kill at 24h; 2-log kill at 48h (murine thigh) | PK/PD parameters, immune component absence |

| Ceftolozane/Tazobactam [1] | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Susceptible (MIC ≤2/4 µg/mL) | 1-log kill in 3/5 isolates at 24h (murine thigh) | Inoculum size, host-pathogen dynamics |

| Ctn[15-34] peptide [2] | Acinetobacter baumannii | Potent activity (low MIC) | Reduced bacterial load with gender-specific effects (murine) | Proteolytic stability, toxicity profiles |

| Ctn retroenantio analog [2] | Acinetobacter baumannii | Improved stability & activity in vitro | Toxic at 5-30 mg/kg; no efficacy (murine) | Unpredicted toxicity, biological recognition |

| Melia azedarach CuO NPs + Cefepime [5] | Multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae | MIC: 1.92 µg/mL (synergistic) | 82% inhibition; improved histopathology (in vivo) | Immune modulation, tissue penetration |

| SK1260 Antimicrobial Peptide [6] | E. coli, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa | MIC: 3.13-12.5 µg/mL | Reduced bacterial burden in organs; improved survival (murine) | Serum binding, biodistribution, immune effects |

The data reveals several critical patterns. First, efficacy magnitude disparities are common, as seen with cefiderocol which demonstrated more rapid killing profiles in vivo compared to ceftolozane/tazobactam despite similar in vitro susceptibility [1]. Second, unpredicted toxicity emerges in vivo for compounds showing excellent in vitro safety profiles, exemplified by the retroenantio analogs of Ctn peptides that proved toxic in mouse models despite promising laboratory data [2]. Third, the influence of host systems significantly modulates outcomes, as demonstrated by CuO nanoparticles that showed enhanced wound healing and immune regulation in vivo beyond their direct antimicrobial effects observed in vitro [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Understanding the methodological approaches for evaluating anti-infectives in both environments is crucial for interpreting correlation data. This section details standard protocols used in recent studies.

In Vitro Susceptibility Testing Protocols

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Assay

- Procedure: Serial dilutions of antimicrobial agents in 96-well microtiter plates containing appropriate culture medium are inoculated with approximately 10^5 CFU/mL of bacterial suspension [6]. Positive (bacterial growth) and negative (sterile) controls are included. After incubation at 37°C for 16-24 hours, the MIC is determined as the lowest concentration showing no visible growth [6].

- Key Reagents: Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth, log-phase bacterial cultures, sterile physiological saline for dilutions.

- Data Analysis: MIC values are reported in µg/mL, with experiments typically performed in triplicate for statistical reliability.

Time-Kill Kinetics Assay

- Procedure: Bacterial suspensions are exposed to antimicrobial concentrations (typically 0.5×, 1×, and 5× MIC) and incubated at 37°C [6]. Aliquots are collected at predetermined time intervals (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 12, and 24 hours), serially diluted, and plated on nutrient agar. After 24 hours of incubation, colony-forming units (CFU) are enumerated.

- Data Analysis: Results are expressed as log10 CFU/mL versus time, with bactericidal activity defined as ≥3-log reduction from initial inoculum.

Biphasic Dissolution System for IVIVC

- Procedure: This advanced system contains aqueous (buffer, 300 mL) and organic (octanol, 200 mL) phases saturated through stirring at 37°C [7]. Drug formulations are introduced into the aqueous phase, with samples simultaneously collected from both phases at multiple time points. The system evaluates both dissolution and partitioning kinetics, providing a more biorelevant assessment for poorly soluble compounds [7].

In Vivo Efficacy Assessment Protocols

Murine Thigh Infection Model

- Procedure: Mice are rendered neutropenic via cyclophosphamide administration (150 mg/kg, 4 days and 1 day before infection) [1]. Thighs are inoculated with approximately 10^6 CFU of bacteria. Human-simulated regimens of antimicrobials are administered starting 2 hours post-infection. Thighs are harvested at predetermined times (24, 48, 72 hours), homogenized, and plated for bacterial quantification.

- Key Parameters: Change in bacterial density from baseline (log10 CFU/thigh), with translational endpoints of 1- and 2-log10 kill [1].

Systemic Infection and Survival Models

- Procedure: Mice are infected intraperitoneally with lethal inocula of pathogens, frequently supplemented with mucin to enhance infection establishment [2]. Test articles are administered prophylactically or therapeutically at various doses. Animals are monitored for morbidity, mortality, and clinical scores for several days. For bacterial burden studies, target organs (liver, spleen, kidney, lung) are harvested, homogenized, and plated for bacterial quantification [6].

The experimental workflow demonstrates the sequential approach to anti-infective evaluation, where promising in vitro candidates progress to increasingly complex in vivo models, culminating in IVIVC analysis that bridges the two environments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful navigation of the in vitro-in vivo continuum requires specialized reagents and materials tailored to anti-infective research. The table below catalogues critical solutions and their applications.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Anti-infective Efficacy Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth [6] | In vitro susceptibility testing | Standardized medium for MIC and time-kill assays ensuring reproducible results |

| Biphasic Dissolution System [7] | IVIVC for poorly soluble drugs | Simultaneously evaluates drug dissolution and partitioning kinetics using aqueous and organic phases |

| OptiPrep Density Gradient Medium [3] | OMV isolation and purification | Separates bacterial outer membrane vesicles from other cellular components for mechanistic studies |

| XTT Cell Proliferation Kit II [4] | Metabolic activity assessment | Measures bacterial viability and metabolic activity after antimicrobial exposure through colorimetric detection |

| Propidium Iodide Stain [6] | Membrane integrity testing | Evaluates membrane disruption by antimicrobial peptides through fluorescence detection of DNA binding |

| Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) [4] | pH measurement studies | Maintains physiological ion balance while measuring alkalinity of intracanal medicaments over time |

| Porcine Mucin [2] | In vivo infection models | Enhances bacterial virulence in animal models by providing protective matrix and immunosuppression |

| Lipolysis Assay Components [8] | Lipid formulation evaluation | Simulates intestinal digestion to predict in vivo performance of lipid-based drug formulations |

Implications for Anti-infective Drug Development

The discordance between in vitro and in vivo environments presents both challenges and opportunities for anti-infective development. The failure of compounds like retroenantio AMP analogs despite promising in vitro profiles underscores the perils of over-relying on simplified systems [2]. Conversely, the successful translation of SK1260 peptide, which demonstrated correlative in vitro and in vivo efficacy against multiple pathogens, highlights the value of robust preclinical models [6].

The emergence of advanced technologies offers promising avenues for bridging the gap. Biorelevant dissolution systems incorporating lipid digestion processes improve predictions for lipid-based formulations [8]. Bacterial outer membrane vesicle research provides insights into resistance mechanisms and potential therapeutic applications [3]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches enables more sophisticated analysis of complex datasets, potentially identifying patterns that predict in vivo performance from in vitro data [9].

Ultimately, recognizing the fundamental differences between these environments enables researchers to design more predictive experiments, interpret results more critically, and make better decisions about which candidates merit progression to clinical trials. This understanding is paramount in an era of escalating antimicrobial resistance, where efficient translation of laboratory discoveries to effective patient therapies is an urgent global priority.

Bacterial biofilms are structured communities of cells encased in a self-produced extracellular matrix and represent one of the most widespread forms of microbial life [10]. In clinical settings, biofilm-associated infections are responsible for approximately 80% of all microbial infections [10]. These include persistent conditions such as endocarditis, osteomyelitis, infections related to cystic fibrosis, and those occurring on medical implants [10]. A hallmark of biofilm-related infections is their recalcitrance to antimicrobial treatment, which frequently leads to chronic infections, implant failure, and increased mortality [10]. This resistance profile observed in clinical settings often starkly contrasts with the susceptibility patterns determined through standard in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST), creating a significant hurdle in anti-infective drug development [11] [12]. This guide examines the mechanisms behind these discrepancies and compares conventional and emerging models for evaluating anti-biofilm efficacy.

Comparative Analysis: Planktonic vs. Biofilm Antimicrobial Susceptibility

Traditional AST methods, such as broth microdilution, primarily assess the susceptibility of free-floating (planktonic) bacteria by determining parameters like the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), which is the lowest concentration that prevents visible growth [13]. However, these methods fail to accurately predict the efficacy of antimicrobials against biofilm-associated infections. The table below summarizes the key differences in how antimicrobials act on these two distinct bacterial lifestyles.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Planktonic and Biofilm Antimicrobial Susceptibility

| Feature | Planktonic Cells (Standard AST) | Biofilm Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Metric | Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) [13] | Minimal Duration for Killing (MDK), e.g., MDK99 [13] |

| Defining Phenotype | Resistance (ability to grow at concentrations above the MIC) [13] | Tolerance (ability to survive exposure to concentrations above the MIC without regrowing) [13] |

| Underlying Mechanisms | Target modification, enzymatic inactivation, efflux pumps [13] | Reduced penetration, metabolic heterogeneity, persister cells, matrix protection [13] [14] |

| Response to Treatment | Typically eradicated by concentrations at or above the MIC | Often survive transient treatment, leading to relapse [13] |

Core Mechanisms of Biofilm-Mediated Treatment Failure

The reduced susceptibility of biofilms is not attributable to a single mechanism but rather a multi-faceted barrier. The following sections detail the primary contributing factors, which often act in concert.

Physical and Chemical Barriers

The Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) matrix acts as a primary barrier by hindering the penetration of antimicrobial agents into the deeper layers of the biofilm [13] [14]. For example, the negatively charged polysaccharide alginate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms can bind and retain the aminoglycoside antibiotic tobramycin [14]. Similarly, an increase in extracellular DNA (eDNA) concentration in Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms reduces the penetration of vancomycin [14]. Furthermore, the matrix can accumulate antibiotic-degrading enzymes, such as β-lactamase, effectively inactivating the drug before it reaches its target [14].

Physiological Heterogeneity

Gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products within the biofilm create a spectrum of microenvironments [13]. This leads to a heterogeneous population of cells with vastly different metabolic states. A key consequence is the presence of slowly growing or dormant cells [13] [12]. Since many antibiotics are only effective against actively growing bacteria, these dormant subpopulations exhibit profound tolerance and can repopulate the biofilm once antibiotic pressure is removed [13].

Evolutionary Dynamics and Adaptive Responses

The spatially structured nature of biofilms, with its gradients of antimicrobial agents, creates 'sanctuaries' where drug concentrations are sub-lethal [13]. These sanctuaries can act as 'stepping stones,' allowing bacterial populations to acquire resistance mutations sequentially, a process that would be impossible in a homogeneous, high-concentration environment [13]. Biofilms also exhibit increased mutation rates compared to planktonic cultures, partly due to oxidative stress, which accelerates genetic adaptation [13]. Additionally, the high cell density and presence of eDNA in the matrix facilitate Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT), promoting the spread of resistance genes [13].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms contributing to biofilm antimicrobial tolerance.

Advanced Experimental Models for Biofilm Research

To bridge the gap between in vitro predictions and in vivo outcomes, researchers are developing more sophisticated models that better mimic the in vivo environment.

In Vitro Flow Models for Anaerobic Co-Culture

Studying host-microbe interactions in the gut has been challenging due to the conflicting oxygen requirements of human cells and obligate anaerobic microbiota. A recent 2025 model addresses this by using a dual-flow channel system with an integrated anaerobization unit [15]. This system maintains stable oxygen levels below 1% in the apical (luminal) channel while supplying oxygen to the intestinal cells from the basolateral side, enabling long-term co-culture of human epithelium with obligate anaerobes like Clostridioides difficile [15]. This model has demonstrated the persistence of C. difficile following vancomycin treatment, replicating a key clinical challenge [15].

Experimental Evolution in Biofilms

Experimental evolution, where bacterial populations are repeatedly exposed to antimicrobial treatment in controlled laboratory settings, provides powerful insights into resistance development. When performed in biofilms, these studies reveal that spatial structure significantly influences evolutionary trajectories [13]. Population fragmentation within the biofilm leads to independently evolving subpopulations, fostering greater genetic diversity and allowing for the fixation of beneficial mutations that might be lost in a well-mixed planktonic culture [13].

Parameters for Predicting Resistance Emergence

Beyond the MIC, several in vitro parameters can help forecast a compound's potential to select for resistance, which is crucial at the hit-to-lead stage of drug development [16].

Table 2: Key In Vitro Parameters for Forecasting Resistance Development

| Parameter | Definition | Utility in Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Mutant Prevention Concentration (MPC) | The antibiotic concentration that prevents the growth of the least susceptible, single-step mutant in a large bacterial population [16]. | Helps define the upper limit of the mutant selection window (MSW); dosing above MPC may suppress resistance. |

| Mutant Selection Window (MSW) | The concentration range between the MIC of the wild-type strain and the MPC [13]. | Antibiotic concentrations within this window enrich for resistant mutants. |

| Frequency of Spontaneous Mutant Selection (FSMS) | The ratio of resistant colony-forming units (CFUs) to the total number of CFUs plated on antibiotic-containing media [16]. | Quantifies the probability that a single-step resistant mutant will arise spontaneously. |

| Minimal Selective Concentration (MSC) | The lowest antibiotic concentration at which the growth rate of a resistant mutant equals that of the wild-type strain [16]. | Defines the lower boundary of the selective window, including at sub-MIC levels. |

The relationship between these parameters and selective pressure is visualized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Models

Selecting appropriate experimental tools is critical for generating clinically relevant data on anti-biofilm efficacy.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biofilm Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biofilm Quantification | Crystal Violet (CV) Staining, Resazurin Viability Staining, Colony Forming Unit (CFU) Enumeration [14] | CV measures total biomass; Resazurin assesses metabolic activity; CFU counts culturable cells. Each measures a different aspect of biofilms. |

| Advanced In Vitro Models | Dual-flow Channel Systems, Organ-on-a-Chip, Anaerobization Units [15] | Create physiologically relevant environments with controlled oxygen gradients and fluid shear stress for host-microbe co-culture. |

| Matrix Targeting Agents | DNase (degrades eDNA), Dispersin B (degrades polysaccharide), N-Acetylcysteine (breaks disulfide bonds) [10] [17] | Enzymatically degrade specific components of the EPS matrix to disrupt biofilm structure and enhance antimicrobial penetration. |

| Anti-Virulence Agents | Quorum Sensing Inhibitors (e.g., AHL analogs), Anti-adhesion coatings [10] [17] | Target bacterial cell-to-cell communication and surface attachment without exerting direct lethal pressure, potentially reducing resistance selection. |

The disconnect between in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy of antimicrobial agents against biofilms remains a significant obstacle in anti-infective development [11]. This discrepancy is rooted in the fundamental physiological, structural, and evolutionary differences between planktonic and biofilm communities. Relying solely on traditional AST, which is designed for planktonic bacteria, leads to poor predictive value for biofilm-associated infections. Success in this field requires the adoption of more sophisticated, physiologically relevant in vitro models that incorporate flow, host cells, and controlled microenvironments, alongside a focus on anti-biofilm specific parameters like the MPC and MDK. By integrating these advanced tools and concepts into the drug development pipeline, researchers can better forecast clinical outcomes and design more effective strategies to combat persistent biofilm infections.

The efficacy of anti-infective therapies is traditionally predicted using in vitro susceptibility tests, such as broth microdilution. However, these routine methods often fail to predict clinical outcomes for device-related infections (DRIs), as they do not account for the biofilm phenotype of bacteria. This guide compares the performance of standard planktonic susceptibility testing with advanced biofilm susceptibility methods, framing the analysis within the critical thesis of in vitro versus in vivo correlation.

Comparison of Susceptibility Testing Methodologies

The following table compares the core methodologies, their underlying principles, and key performance metrics.

Table 1: Methodological Comparison of Planktonic vs. Biofilm Susceptibility Testing

| Feature | Routine Planktonic Testing (e.g., Broth Microdilution) | Advanced Biofilm Susceptibility Testing (e.g., Calgary Biofilm Device) |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Phenotype | Free-floating (Planktonic) | Surface-attached community (Biofilm) |

| Key Output Metric | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) | Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC) |

| Correlation with DRI Outcomes | Poor. Routinely underestimates the antibiotic concentration required for eradication. | Strong. Better predicts the need for higher doses or combination therapies. |

| Experimental Data (S. aureus vs. Oxacillin) | MIC: 0.5 µg/mL (Susceptible) | MBEC: >256 µg/mL (Resistant) |

| Underlying Reason for Discrepancy | Tests bacteria in a vulnerable, non-adherent state. | Accounts for matrix protection, reduced metabolic activity, and persister cells. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Broth Microdilution for MIC Determination This protocol is the reference method for determining the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) against planktonic bacteria.

- Preparation: Prepare a logarithmic dilution series (e.g., two-fold) of the antibiotic in a suitable broth medium (e.g., Mueller-Hinton Broth) in a 96-well microtiter plate.

- Inoculation: Standardize a bacterial suspension to approximately 5 x 10^5 CFU/mL in the same broth. Add a equal volume of this suspension to each well of the antibiotic dilution series. Include growth control (bacteria, no antibiotic) and sterility control (broth only) wells.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate under optimal conditions for the test organism (e.g., 35±2°C for 16-20 hours).

- Result Interpretation: The MIC is the lowest concentration of antibiotic that completely inhibits visible growth of the organism.

Protocol 2: Calgary Biofilm Device (CBD) for MBEC Determination This protocol is used to determine the Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC), which measures the concentration required to kill biofilm-encased bacteria.

- Biofilm Formation: Inoculate a specialized CBD lid (with 96 pegs) into a microtiter plate containing a standardized bacterial suspension. Incubate the assembly under static conditions for a defined period (e.g., 24-48 hours) to allow biofilms to form on the pegs.

- Biofilm Maturation: After incubation, gently rinse the peg lid in a neutral buffer to remove non-adherent planktonic cells.

- Antibiotic Challenge: Transfer the peg lid to a new "challenge" plate containing a two-fold dilution series of the antibiotic in broth. Incubate for a further 24 hours.

- Biofilm Disruption and Viability Assessment: Remove the peg lid, rinse again to remove residual antibiotic, and then transfer it to a "recovery" plate containing a neutral buffer. Sonicate or vortex the plate to dislodge and disaggregate biofilm cells from the pegs. Serially dilute the recovered suspension and spot-plate onto agar plates to enumerate viable colony-forming units (CFUs).

- Result Interpretation: The MBEC is the lowest concentration of antibiotic that results in a ≥3-log10 reduction (99.9% kill) in viable biofilm bacteria compared to the growth control.

Visualizing the In Vitro / In Vivo Disconnect

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow of the testing methods and the core biological reasons for the failure of routine tests.

Workflow: Routine MIC Test

Biofilm Resistance Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biofilm Susceptibility Research

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Calgary Biofilm Device (CBD) | A standardized peg-lid apparatus for high-throughput cultivation and testing of biofilms. |

| Crystal Violet Stain | A simple dye used for the semi-quantitative assessment of total biofilm biomass. |

| Resazurin Viability Stain | An oxidation-reduction indicator used to measure metabolic activity within biofilms. |

| Mueller-Hinton Broth | The standardized growth medium specified for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. |

| Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) | A general-purpose growth medium used for the enumeration of viable bacteria (CFU counting). |

| Polystyrene Microplates | The standard platform for broth microdilution (planktonic) and biofilm assays. |

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CAMHB) | A refined broth that ensures consistent cation concentrations, critical for reliable antibiotic activity, particularly with aminoglycosides. |

In anti-infective drug development, a profound disconnect often exists between promising in vitro results and clinical efficacy. This translational gap stems primarily from the failure of simplistic laboratory models to account for the intricate physiological complexity of living organisms. While in vitro susceptibility testing provides essential initial data on antimicrobial activity, it occurs in an environment largely devoid of host immunity, pharmacokinetic (PK) variables, and biological barriers that determine drug distribution to infection sites. The transition from static in vitro conditions to dynamic in vivo systems introduces multifaceted challenges including protein binding, tissue penetration limitations, variable metabolic conditions, and active host immune responses that collectively modulate therapeutic outcomes. Understanding these complex interactions is critical for accurate prediction of clinical efficacy and optimization of dosing regimens for anti-infective agents.

Key Physiological Barriers in Anti-Infective Efficacy

The Critical Role of Host Immunity

In vivo infection models demonstrate that host immune status dramatically influences antibacterial efficacy, a factor completely absent in standard in vitro testing. The neutropenic murine thigh infection model, a cornerstone of anti-infective pharmacodynamics, explicitly controls for this variable by rendering mice immunocompromised before infection [18]. This model allows researchers to isolate drug effects from immune-mediated clearance, providing a standardized platform for comparing antimicrobial activity under defined conditions. However, this represents only one point on the spectrum of immune competence that clinicians encounter in human populations.

The immune system interacts with anti-infective therapies through multiple mechanisms:

- Synergistic clearance: Immune cells such as neutrophils and macrophages may work in concert with antibiotics to eliminate pathogens more effectively than either component alone.

- Altered pharmacokinetics: Inflammation can change blood flow, capillary permeability, and protein binding, thereby modifying drug distribution to infection sites.

- Differential expression in immunocompromised states: The efficacy of bacteriostatic versus bactericidal agents may vary significantly depending on host immune status, with bactericidal agents generally preferred in immunocompromised patients.

Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Considerations

Pharmacokinetics (what the body does to the drug) and pharmacodynamics (what the drug does to the body) collectively determine anti-infective efficacy in vivo. The integration of these disciplines through PK/PD modeling has become essential for translating in vitro activity to in vivo effectiveness [18]. Key principles include:

- Time-dependent versus concentration-dependent killing: Different antibiotic classes exhibit distinct killing patterns that inform optimal dosing strategies. Beta-lactams typically show time-dependent activity, requiring concentrations to remain above the MIC for extended periods, while aminoglycosides display concentration-dependent killing, benefiting from higher peak concentrations.

- Post-antibiotic effects: Some antibiotics continue suppressing bacterial growth even after concentrations fall below the MIC, an phenomenon only observable in dynamic systems.

- Protein binding impact: Only unbound drug molecules can exert antimicrobial activity, making protein binding a critical determinant of efficacy that varies between in vitro media and in vivo conditions [19].

Tissue Distribution and Penetration Barriers

Perhaps the most significant translational challenge lies in achieving adequate drug concentrations at the site of infection, which often differs substantially from plasma levels measured in pharmacokinetic studies [20]. Multiple factors complicate tissue distribution:

- Blood-tissue barriers: Capillary physiology varies significantly across tissues, with permeability coefficients differing by orders of magnitude between organs [20]. The blood-brain barrier represents the most extreme example, but other tissues like bone, prostate, and abscess cavities also present significant penetration challenges.

- Interstitial fluid as the target site: For most bacterial infections, the relevant compartment is the interstitial space fluid (ISF) where extracellular pathogens reside [20]. Drug concentrations in this compartment often differ markedly from plasma levels due to capillary wall resistance, pH partitioning, and active transport mechanisms.

- Methodological misconceptions: Traditional approaches to measuring tissue concentrations through homogenization provide misleading data by admixing intracellular, extracellular, and vascular compartments [20]. More sophisticated techniques like microdialysis now enable direct measurement of unbound drug concentrations in the ISF, providing more pharmacologically relevant data [19].

Table 1: Key Physiological Factors Creating Discrepancies Between In Vitro and In Vivo Anti-infective Efficacy

| Physiological Factor | In Vitro Simplification | In Vivo Complexity | Impact on Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host Immunity | Absent | Variable immune competence | Can synergize with or compensate for drug activity |

| Protein Binding | Often standardized or ignored | Variable binding to plasma and tissue proteins | Reduces free, active drug concentrations |

| Tissue Penetration | Uniform drug distribution | Barriers based on capillary structure and physiology | Creates concentration gradients between plasma and infection sites |

| Pathophysiology | Optimal, uniform growth conditions | Altered pH, oxygen tension, nutrient availability | Affects bacterial growth rate and antimicrobial susceptibility |

Comparative Analysis: Cefiderocol versus Ceftolozane/Tazobactam

Experimental Methodology and Translational Model

A recent comparative study exemplifies the importance of physiological considerations when evaluating anti-infective efficacy [1]. This investigation employed a 72-hour murine thigh infection model against five clinical difficult-to-treat Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates to compare cefiderocol and ceftolozane/tazobactam. The methodology incorporated several key physiological elements:

- Human-simulated regimens: The study utilized human-simulating regimens of ceftolozane/tazobactam (2/1 g IV q8h) and cefiderocol (2 g IV q8h) to replicate human pharmacokinetic profiles in the murine model, enhancing translational relevance [1].

- Immunocompromised host: The neutropenic murine model controlled for variability in immune response, allowing isolation of drug-specific effects [1].

- Extended duration: The 72-hour timeframe enabled assessment of both initial killing and potential resistance development over multiple drug exposures.

- Bacterial density measurements: Efficacy was quantified as change in bacterial density from starting inoculum, with comparison to translational endpoints of 1- and 2-log₁₀ kill [1].

Efficacy and Killing Kinetics Comparison

Despite both agents demonstrating susceptibility against the tested isolates in vitro, significant differences emerged in their in vivo performance profiles [1]:

- Rate of killing: Cefiderocol achieved 1-log₁₀ kill against all five isolates by 24 hours, while ceftolozane/tazobactam reached this endpoint in only three of five isolates.

- Magnitude of effect: Cefiderocol produced 2-log₁₀ kill in all isolates by 48 hours, whereas ceftolozane/tazobactam required 72 hours to achieve this level of killing in four isolates.

- Bacterial eradication: The cefiderocol treatment group showed 17% bacterial eradication versus 8% in the ceftolozane/tazobactam group after exposure to human-simulated regimens.

Table 2: In Vivo Efficacy Comparison Between Cefiderocol and Ceftolozane/Tazobactam Against Difficult-to-Treat P. aeruginosa in a Murine Thigh Infection Model [1]

| Efficacy Parameter | Cefiderocol | Ceftolozane/Tazobactam |

|---|---|---|

| 1-log₁₀ Kill at 24h | 5/5 isolates | 3/5 isolates |

| 2-log₁₀ Kill at 48h | 5/5 isolates | 0/5 isolates |

| 2-log₁₀ Kill at 72h | 5/5 isolates | 4/5 isolates |

| Bacterial Eradication | 17% of cultures | 8% of cultures |

| Resistance Development | Not detected | Not detected |

Mechanistic Insights and Physiological Advantages

The superior performance of cefiderocol in this model can be attributed to its unique mechanism of action that specifically addresses physiological challenges:

- Siderophore functionality: Cefiderocol utilizes the bacterial iron transport system to actively cross outer membranes, bypassing traditional porin channels and efflux pumps that often mediate resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa [1].

- Enhanced tissue penetration: The siderophore mechanism may facilitate improved penetration through physiological barriers that limit distribution of other beta-lactams.

- Stability against degradation: Cefiderocol demonstrates greater stability against beta-lactamases, including extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases, which are frequently expressed by difficult-to-treat pathogens.

Methodological Framework for Translation

Integrated PK/PD Modeling Approaches

Model-based translation represents a sophisticated alternative to traditional PK/PD index approaches that better accounts for physiological complexity [18]. The development of a mechanism-based PK/PD model for the FabI inhibitor afabicin illustrates this paradigm:

- In vitro model development: A PK/PD model was built using 162 static in vitro time-kill curves evaluating afabicin desphosphono against 21 Staphylococcus aureus strains [18].

- Bacterial dynamics modeling: The model incorporated two bacterial states (growing/susceptible and dormant/non-susceptible) to account for heterogeneous subpopulations with different susceptibility profiles [18].

- Translational prediction: When combined with a mouse PK model, parameters estimated from in vitro data successfully predicted in vivo bacterial counts at 24 hours within ±1 log margin for most dosing groups without parameter re-estimation [18].

- Parameter refinement: Subsequent estimation from in vivo data revealed that the EC₅₀ was 38-45% lower in vivo compared to in vitro, highlighting important physiological differences in drug activity [18].

Measuring Therapeutically Relevant Concentrations

Accurate assessment of drug exposure at infection sites requires methodological sophistication beyond traditional plasma monitoring:

- Unbound drug concentrations: Only unbound drug molecules can exert antimicrobial activity, making protein binding a critical determinant of efficacy [19]. Techniques for direct measurement of free drug concentrations include microdialysis, ultrafiltration, and equilibrium dialysis.

- Interstitial fluid sampling: For most extracellular infections, the relevant compartment is the interstitial space fluid where pathogens reside [20]. Microdialysis enables direct measurement of unbound antibiotic concentrations in this compartment through semi-permeable membranes implanted in tissues [19].

- Accounting for protein binding variability: Protein binding exhibits concentration-dependent behavior for some antibiotics (e.g., ceftriaxone, ertapenem) and may change in disease states due to alterations in plasma protein concentrations [19].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Evaluating Physiological Complexity in Anti-infective Studies

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Neutropenic Murine Thigh Model | Standardized assessment of in vivo efficacy independent of host immunity | Preclinical PK/PD studies for antibacterial agents [18] |

| Microdialysis Systems | Direct measurement of unbound drug concentrations in interstitial fluid | Tissue penetration studies for antibiotics with poor distribution [19] |

| HepG2 Cell Line | In vitro model for mRNA vaccine translation and protein expression | Potency assessment for mRNA-based vaccines [21] |

| Mechanism-Based PK/PD Models | Mathematical frameworks describing time course of antibiotic effects | Translation from in vitro time-kill data to in vivo efficacy prediction [18] |

Implications for Anti-Infective Drug Development

Optimizing Dosing Strategies

Understanding physiological complexity enables more rational design of dosing regimens that maximize efficacy while minimizing toxicity and resistance development:

- Tissue penetration-informed dosing: For antibiotics with poor penetration to specific sites of infection (e.g., central nervous system, prostate), higher doses or alternative administration routes may be necessary to achieve therapeutic concentrations [20].

- Protein binding considerations: Highly protein-bound antibiotics may require dose adjustments in patients with altered protein binding capacity (e.g., malnutrition, liver disease, critical illness) [19].

- Immune status-adapted therapy: Immunocompromised patients often require more aggressive antibacterial therapy, including higher doses, combination therapy, or preferentially bactericidal agents.

Future Directions and Innovations

Several emerging approaches show promise for better incorporating physiological complexity into anti-infective development:

- Advanced infection models: More sophisticated in vitro and in vivo models that better mimic human physiology, including organ-on-a-chip systems and humanized mouse models.

- Imaging technologies: Non-invasive imaging techniques that enable real-time monitoring of infection progression and drug distribution in living organisms.

- Systems pharmacology: Integrated modeling approaches that incorporate host-pathogen-drug interactions across multiple biological scales from molecular to whole-organism levels.

- Biomarker development: Identification of biomarkers that predict tissue penetration and efficacy before clinical trials.

The translational gap between in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy remains a fundamental challenge in anti-infective development. The comparative analysis of cefiderocol and ceftolozane/tazobactam demonstrates how agents with similar in vitro susceptibility profiles can exhibit meaningfully different performance in physiologically relevant models. Successful translation requires meticulous attention to host immunity, pharmacokinetic variability, and tissue distribution barriers that collectively determine drug exposure at infection sites. Advanced modeling approaches that integrate in vitro and in vivo data, coupled with sophisticated sampling techniques that measure therapeutically relevant unbound drug concentrations at target sites, provide powerful tools for bridging this translational divide. As anti-infective development confronts the escalating challenge of antimicrobial resistance, accounting for physiological complexity will become increasingly critical for optimizing therapeutic outcomes and extending the utility of existing agents.

Advanced Models and PK/PD Strategies for Robust Correlation

The Trajectory of In Vitro Models: From Static Wells to Dynamic Microphysiological Systems

The journey of in vitro models began with simple two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures in static well plates. While these systems provided a foundational platform for basic research, they suffered from significant limitations, including distorted cell morphology, loss of tissue-specific functions, and an inability to replicate the complex three-dimensional (3D) architecture and dynamic cellular interactions found in living tissues [22]. This lack of physiological relevance often led to experimental data that poorly predicted human clinical responses, creating a critical gap in drug development [23].

The pressing need for more predictive models, coupled with ethical imperatives to reduce animal testing (as reinforced by policies like the FDA Modernization Act 2.0), has accelerated the development of advanced systems [22]. This evolution has progressed through several key stages:

- 2D Static Cultures: The traditional workhorse, useful for high-throughput screening but lacking physiological context.

- 3D Organoids and Spheroids: These models form cell aggregates that better mimic the spatial organization and some functional aspects of native tissues, bridging the gap between 2D cultures and whole organs [22].

- Organ-on-a-Chip (OoC) Systems: Representing the current state-of-the-art, OoC technology leverages microfluidics to create dynamic, perfused microenvironments. These chips can house miniature engineered tissues under conditions that mimic physiological fluid flow, mechanical forces (such as cyclic stretch in lungs and peristalsis in guts), and complex tissue-tissue interfaces [24] [23].

The integration of patient-derived organoids (PDOs) into OoC systems is a particularly powerful advancement. PDOs retain key genetic, phenotypic, and pathological features of the parent tumor, achieving high predictive accuracy—for example, >87% in colorectal cancer drug-response studies [22]. This convergence of biology and engineering has given rise to sophisticated microphysiological systems (MPS) that are transforming the study of human physiology, disease mechanisms, and drug efficacy.

Quantitative Comparison of In Vitro Model Capabilities

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of different in vitro models, highlighting the evolution in physiological relevance and application potential.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of In Vitro Model Systems

| Feature | Traditional 2D Static Models | 3D Organoid/Spheroid Models | High-Throughput Organ-on-Chip (e.g., OrganoPlate) | Multi-Organ Chip Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Complexity | Low; monolayer culture, no 3D structure [22] | Moderate; 3D architecture, preserves some heterogeneity [22] | High; 3D tissue embedded in ECM, perfused tubules, apical/basolateral access [25] | Very High; multiple engineered tissues linked by vascular perfusion [23] |

| Throughput & Scalability | Very High (e.g., 384-well plates) | Moderate to High | High (40, 64, or 96 independent chips per plate) [25] | Low to Moderate; complex operation [25] |

| Dynamic Microenvironment | No; static culture | Limited; often static | Yes; continuous perfusion, controlled shear stress [25] | Yes; recirculating flow mimics systemic blood circulation [23] |

| Key Advantages | Simplicity, cost-effectiveness, high-throughput compatibility | Captures tumor heterogeneity, patient-specific [22] | Scalability for screening, direct compound access to tissue, no artificial membranes [25] | Studies inter-organ crosstalk, systemic drug PK/PD, and organism-level responses [23] |

| Primary Applications | Initial high-throughput drug screening, basic cell biology | Disease modeling, personalized therapy screening [22] | Complex tissue and disease modeling, transport and permeability assays, migration studies [25] | Preclinical assessment of drug safety, efficacy, and mechanistic toxicology [26] [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays in Anti-Infective Research

Establishing a correlation between in vitro potency and in vivo efficacy is a cornerstone of anti-infective development. The following protocols detail both traditional and advanced methods.

Protocol 1: Traditional Time-Kill Kinetics Assay

This method evaluates the temporal dynamics of antibacterial activity by tracking changes in bacterial concentration after antibiotic exposure [27].

Methodology:

- Inoculum Preparation: Prepare a bacterial suspension of approximately 10^5-10^6 CFU/mL in a suitable broth medium [27].

- Antibiotic Exposure: Add the antibiotic to the suspension at predetermined concentrations (e.g., 0.5x, 1x, 2x, and 4x the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)).

- Incubation and Sampling: Incubate the culture under controlled conditions (e.g., 37°C). Take samples at regular intervals (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 6, and 24 hours).

- Viable Count Determination: Serially dilute each sample and plate it onto agar plates. After incubation, count the colony-forming units (CFU) to determine the number of viable bacteria at each time point.

- Data Analysis: Plot the log10 CFU/mL against time for each antibiotic concentration. The resulting time-kill curves show whether the antibiotic effect is bactericidal (≥3-log reduction in CFU/mL) or bacteriostatic [27].

Limitations: This assay is performed at a constant antibiotic concentration, which does not replicate the fluctuating concentrations seen in the human body. It also often lacks continuous nutrient supply and does not account for metabolites or host immune factors [27].

Protocol 2: Organ-on-a-Chip Model for Host-Pathogen Interaction and Drug Efficacy

This protocol leverages a perfused microfluidic system to create a human-relevant model for studying infections.

Methodology:

- Chip Priming and ECM Seeding:

- Use a microfluidic chip such as the OrganoPlate (3-lane 40 or 64) or Emulate Chip-S1 [25] [26].

- Inject an extracellular matrix (ECM) hydrogel, like collagen-I, into the central gel channel and allow it to polymerize.

- Flow culture medium through the two adjacent perfusion channels to condition the chip.

- Cell Seeding and Tissue Formation:

- Seed relevant epithelial or endothelial cells into the channels to form tissue barriers or perfused tubules. For instance, in a lung model, primary human airway epithelial cells can be cultured to create a mucociliary epithelium [23].

- Allow the tissues to differentiate and mature under perfusion for several days, often applying physiological cues like fluid shear stress or cyclic mechanical stretch.

- Infection and Drug Treatment:

- Introduce the pathogen (e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae or SARS-CoV-2) into the apical (luminal) channel of the tissue model [26].

- For therapeutic intervention, add the anti-infective candidate to the perfusion medium (basolateral side) or directly to the apical surface, allowing for the study of penetration and efficacy in a physiologically relevant context.

- Endpoint Analysis:

- Transepithelial/Transendothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER): Measure in real-time to monitor barrier integrity [24].

- Effluent Collection: Analyze collected perfusate for inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-8) via ELISA, and for bacterial load.

- Immunofluorescence Imaging: Fix and stain the tissues for confocal microscopy to visualize pathogen attachment, invasion, and host cell damage.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The transition from static models to dynamic OoCs involves integrating multiple biological and engineering principles. The diagram below outlines the key components and workflow for establishing a physiologically relevant in vitro model for anti-infective testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Building and utilizing advanced in vitro models requires a suite of specialized reagents and instruments. The following table details key components of the modern researcher's toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Organ-on-a-Chip and Advanced In Vitro Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| OrganoPlate | A microfluidic 3D cell culture platform in a standard microtiter plate format (e.g., 40-, 64-, or 96-independent chips), enabling perfusion without pumps or tubing [25]. | High-throughput 3D tissue culture, barrier integrity assays, and transport studies [25]. |

| Chip-S1 (Emulate) | A PDMS-based microfluidic chip with a flexible membrane that can be subjected to cyclic stretch to mimic physiological movements like breathing or peristalsis [26]. | Lung airway and alveolus models, gut models, and studying effects of mechanical strain on cells [23]. |

| Chip-R1 (Emulate) | A rigid, non-PDMS chip designed for minimal drug absorption, making it ideal for ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) and toxicology studies [26]. | Accurate pharmacokinetic modeling and compound toxicity screening. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Hydrogels | Natural or synthetic hydrogels (e.g., collagen I, Matrigel) that provide a 3D scaffold to support cell growth, differentiation, and tissue morphogenesis [25] [22]. | Providing a physiological scaffold for embedding cells and forming 3D tissue structures in chips [25]. |

| Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) | 3D tissue cultures derived from a patient's own stem or tumor cells, retaining the genetic and phenotypic features of the original tissue [22]. | Creating personalized disease models for drug screening and studying patient-specific treatment responses [22]. |

| Transepithelial/Transendothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) Instrument | A device to measure electrical resistance across a cellular barrier, serving as a quantitative, real-time indicator of barrier integrity and function [24]. | Assessing the formation and breakdown of biological barriers (e.g., intestinal, blood-brain barrier) in OoC models. |

The evolution from static wells to dynamic, physiologically relevant Organ-on-a-Chip models marks a paradigm shift in preclinical research. By recapitulating critical aspects of human biology—such as 3D tissue architecture, vascular perfusion, mechanical cues, and multi-organ interactions—these advanced MPS offer a powerful platform to bridge the long-standing gap between in vitro potency and in vivo efficacy [23]. For anti-infective research, this means the potential to better model host-pathogen interactions, predict clinical outcomes of antibiotic therapies, and accelerate the development of novel treatments against resistant infections. As the technology continues to standardize and scale, with the emergence of platforms like the AVA Emulation System that offers 96-chip throughput, the adoption of OoCs is poised to enhance the predictive power of drug development, reduce reliance on animal models, and usher in a new era of human-relevant biological research [26].

In the demanding landscape of drug development, particularly in oncology and anti-infective therapy, Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) has emerged as a transformative strategy. MIDD employs pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling and simulation to inform decision-making and optimize drug development pipelines [28]. A pivotal concept within this paradigm is the Tumor Static Concentration (TSC), a theoretical drug concentration that, if maintained constant in the plasma, results in tumor stasis—where the tumor volume neither increases nor decreases compared to the initial volume [29]. The TSC serves as a powerful, quantitative efficacy index that bridges experimental data and clinical outcomes.

The establishment of a robust In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) is a primary application of TSC. IVIVC creates a predictive link between a drug's in vitro activity (e.g., cell-killing in a lab dish) and its in vivo efficacy (e.g., tumor growth inhibition in a mouse) [29]. For anti-infective drugs, the challenge is analogous: correlating in vitro microbiological activity with in vivo treatment efficacy in a complex host environment. The power of TSC lies in its ability to condense complex PK/PD relationships from both in vitro and in vivo experiments into a single, comparable metric, enabling more reliable translation from preclinical models to human clinical doses [30].

TSC Concepts and Modeling Across Therapeutic Areas

The TSC framework is versatile and can be adapted to various drug modalities, from traditional small molecules to complex biologics. The core principle involves using mathematical models to describe the system's dynamics—whether tumor cell growth or pathogen proliferation—and calculating the drug exposure level required to halt that growth.

Quantitative Foundation of TSC

The TSC is derived from the system equations of semimechanistic PK/PD models. In its fundamental form, it is the drug concentration (C) that satisfies the condition where the rate of tumor cell growth is exactly balanced by the rate of drug-induced cell kill, resulting in a net growth rate of zero:

TSC = (λ / k)

where λ represents the first-order growth rate constant of the tumor cells and k represents the second-order rate constant for the drug-induced tumor cell kill [29]. In practice, for novel compounds, these parameters (λ and k) are estimated by fitting the PK/PD model to experimental data, such as longitudinal tumor volume measurements from xenograft mouse studies [30]. The resulting TSC value provides a crucial benchmark: if the average steady-state drug concentration in plasma exceeds the TSC, tumor regression is expected; if it falls below, tumor growth is likely to continue.

Application in Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs)

ADCs represent a promising but complex class of targeted cancer therapeutics. Establishing IVIVC for ADCs is critical for prioritizing lead candidates. A seminal study developed IVIVC for 19 different ADCs by calculating both an in vitro TSC (TSC~in vitro~) and an in vivo TSC (TSC~in vivo~) [29].

- TSC~in vitro~ was determined using a kinetic cell cytotoxicity assay, representing the concentration resulting in no net change in cell number compared to the start of the experiment.

- TSC~in vivo~ was determined by modeling Tumor Growth Inhibition (TGI) data from human tumor xenograft-bearing mice.

The comparison revealed a linear and positive correlation (Spearman's rank correlation coefficient = 0.82) between TSC~in vitro~ and TSC~in vivo~ across the 19 ADCs. On average, the TSC~in vivo~ was approximately 27 times higher than the TSC~in vitro~, a scaling factor that can be used to predict in vivo potency from in vitro data for new ADC candidates, thereby streamlining the selection process [29].

Translation to Clinical Dosing

The TSC concept is directly applicable to predicting human efficacious doses. A case study on RC88, a mesothelin-targeting ADC, demonstrated this translation. Researchers used three different semimechanistic PK/PD models (Simeoni, Jumbe, and Hybrid) to characterize TGI data from ovarian and lung cancer xenograft models and calculate the TSC in mice [30]. This preclinical TSC was then integrated with a prediction of human PKs, derived from a target-mediated drug disposition model built using monkey PK data, to back-calculate the required human dose expected to achieve TSC-level exposures. This integrated approach predicted an efficacious clinical dose range of 0.82 to 1.96 mg/kg administered weekly for RC88 [30].

TSC and IVIVC in Anti-Infective Drug Development

The principles of MIDD and correlation are equally critical in anti-infective drug development, which faces exciting yet challenging opportunities due to the rising threat of antimicrobial resistance [28]. The early application of MIDD at regulatory agencies involved characterizing drug molecules through population PK/PD modeling and IVIVC [28].

Table 1: Key PK/PD Indices and Correlations in Anti-Infective Development

| PK/PD Index | Definition | Role in IVIVC & MIDD |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) | The lowest concentration of an antimicrobial that prevents visible growth of a microorganism. | A static, traditional endpoint used for susceptibility testing and dose stratification [28]. |

| Tumor Static Concentration (TSC) Concept | The theoretical drug exposure that results in net stasis of a pathogen population. | A dynamic, model-informed index that can integrate time-varying drug effects and host factors for superior dose optimization [28]. |

| Integrated Host-Pathogen Models | Models that incorporate host immune responses and pathogen-drug interactions. | Represents the evolving complexity in MIDD to better predict clinical outcomes for non-traditional anti-infectives [28]. |

In contrast to static PK/PD indices like the MIC, the model-informed approach embodied by the TSC concept can better describe the time-varying anti-infective effects of a drug [28]. This is crucial because the in vivo environment is dynamic, and a deeper understanding of "drug-pathogen-host" interactions is needed. For instance, the host's immune response can create microenvironments that either facilitate or impede pathogen clearance [28]. Modern MIDD frameworks are thus expanding to incorporate these host system dynamics, providing a more comprehensive basis for predicting the efficacy of novel anti-infectives, such as bacteriophages and immunomodulating agents [28].

Experimental Protocols for Establishing IVIVC

A robust IVIVC requires carefully designed and executed experiments to generate high-quality data for PK/PD modeling.

Protocol for In Vitro TSC Determination (ADC Example)

This protocol outlines the key steps for establishing an in vitro efficacy matrix [29].

- Kinetic Cell Cytotoxicity Assay: Seed cancer cells into multi-well plates and allow them to adhere.

- ADC Exposure: Treat the cells with a range of ADC concentrations. Include control wells with vehicle only.

- Longitudinal Cell Viability Measurement: Use a real-time cell analysis (RTCA) system or similar technology to monitor cell proliferation and viability kinetically over a defined period (e.g., 3-5 days), rather than at a single endpoint.

- Data Analysis and Model Fitting: Fit the resulting time-course viability data to a mathematical model that describes cell growth and ADC-induced killing. The model parameters are estimated from this data fit.

- TSC~in vitro~ Calculation: Using the fitted model, calculate the theoretical ADC concentration that would result in the final cell number being equal to the initial cell number. This concentration is the TSC~in vitro~.

Protocol for In Vivo TSC Determination (ADC Example)

This protocol describes the generation of in vivo data for PK/PD modeling [30].

- Xenograft Model Establishment: Implant human tumor cells (e.g., OVCAR-3 ovarian cancer or H292 lung cancer cells) subcutaneously into immunodeficient mice (e.g., Balb/c nude mice).

- Randomization and Dosing: Once tumor volumes reach a predetermined size (~250 mm³), randomize mice into different treatment groups. Groups typically include a vehicle control and multiple dose levels of the ADC (e.g., 0.75, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg).

- Drug Administration and PK Sampling: Administer the ADC intravenously according to the planned schedule (e.g., once weekly for 3 weeks). Collect blood samples at various time points post-dose from a subset of animals to characterize the ADC's pharmacokinetic profile.

- Tumor Volume Measurement: Measure tumor dimensions (length and width) using calipers twice weekly. Calculate tumor volume using the formula:

Volume (mm³) = 0.5 × (width²) × length. - PK/PD Modeling and TSC~in vivo~ Calculation: The longitudinal tumor volume data and corresponding PK data are co-modeled using a semimechanistic PK/PD model (e.g., Simeoni, Jumbe, or Hybrid models). The TSC~in vivo~ is derived as a secondary parameter from the fitted model, representing the constant plasma concentration that would lead to tumor stasis.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Conceptual Framework of TSC and IVIVC

This diagram illustrates the core workflow of using TSC to bridge in vitro and in vivo data.

Diagram 1: TSC-based IVIVC workflow for human dose prediction.

MIDD Workflow in Anti-Infective Development

This diagram outlines the expanded MIDD workflow for anti-infectives, incorporating host-pathogen-drug interactions.

Diagram 2: MIDD framework integrating pathogen, drug, and host data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for TSC and IVIVC Studies

| Category | Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Models | Cancer Cell Lines (e.g., OVCAR-3, H292) [30] | In vitro potency screening and establishing xenograft models for in vivo efficacy studies. |

| Immunodeficient Mice (e.g., Balb/c nude) [30] | Host for human tumor xenografts to evaluate in vivo drug efficacy in a pre-clinical setting. | |

| Cynomolgus Monkeys [30] | Non-human primate model used for toxicology and translational PK studies to predict human PK. | |

| Key Reagents | Tool ADC / Drug Candidate [30] | The therapeutic molecule being evaluated, with a well-characterized Drug-Antibody Ratio (DAR) for ADCs. |

| Detection Antibodies (e.g., anti-MMAE, HRP-conjugated) [30] | Critical for developing immunoassays (ELISA) to quantify drug concentrations in biological matrices. | |

| Analytical Instruments | ELISA Plate Reader [30] | Measures drug concentration in serum/plasma samples for PK analysis. |

| Real-Time Cell Analyzer (RTCA) [29] | Enables kinetic, label-free monitoring of cell proliferation and cytotoxicity for in vitro TSC determination. | |

| Software & Models | PK/PD Modeling Software (e.g., NONMEM, Monolix, R) | Platform for building, validating, and simulating semimechanistic PK/PD models to derive TSC. |

| Semimechanistic Models (Simeoni, Jumbe, Hybrid) [30] | Pre-defined model structures that describe tumor growth and drug-induced killing, used for TSC calculation. |

The integration of Tumor Static Concentration (TSC) within a PK/PD modeling framework provides a powerful, quantitative approach to bridging in vitro potency and in vivo efficacy. This methodology enables a more rational and efficient path for drug development, from triaging lead candidates to predicting human efficacious doses. The demonstrated success of this approach in complex modalities like ADCs, coupled with its logical extension into the critical field of anti-infective research through advanced MIDD practices, underscores its transformative potential. As drug discovery confronts increasingly challenging targets and the urgent threat of antimicrobial resistance, model-informed strategies like TSC-based IVIVC will be indispensable for accelerating the delivery of novel therapies to patients.

Semi-mechanistic mathematical models represent a powerful methodology in quantitative pharmacology and therapeutics development, seamlessly integrating theoretical mechanism-based principles with empirical data-driven approaches. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of these modeling frameworks within the context of anti-infective and oncology drug development, with particular emphasis on their role in establishing robust in vitro-in vivo correlations (IVIVC). We examine fundamental model structures, experimental methodologies for parameter quantification, and implementation protocols across therapeutic domains. By systematically comparing alternative modeling approaches through structured tables and visual workflows, this guide aims to equip researchers with practical frameworks for selecting appropriate model structures based on specific research objectives, data availability, and biological complexity. The integration of these quantitative approaches provides a powerful platform for accelerating therapeutic optimization and advancing personalized medicine strategies across diverse disease areas.

Semi-mechanistic mathematical models have emerged as indispensable tools in biomedical research and therapeutic development, occupying a crucial middle ground between purely phenomenological models and fully mechanistic biological simulations [31]. These models incorporate key biological processes—such as drug exposure, pathogen/tumor growth, and treatment-induced decay—while remaining mathematically tractable for parameter estimation and prediction [32]. In anti-infective research, they provide a quantitative framework for bridging in vitro potency assessments with in vivo efficacy predictions, addressing a fundamental challenge in drug development [21].

The core strength of semi-mechanistic models lies in their ability to integrate known biology while maintaining computational feasibility. Unlike black-box models that merely describe input-output relationships, semi-mechanistic models incorporate fundamental biological principles such as tumor growth kinetics [32], antibiotic pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) relationships [33], and immune response dynamics [31]. This balanced approach enables researchers to not only predict system behavior but also to gain insights into underlying biological mechanisms driving observed responses.

Within the context of anti-infective efficacy research, establishing robust correlations between in vitro measurements and in vivo outcomes remains a critical challenge with significant implications for drug development efficiency and clinical translation [21]. This review systematically compares semi-mechanistic modeling approaches across therapeutic domains, providing researchers with structured frameworks for model selection, implementation, and validation in preclinical and clinical settings.

Theoretical Foundations of Semi-Mechanistic Modeling

Core Mathematical Frameworks

Semi-mechanistic models typically employ differential equation systems to capture the dynamic interactions between system components. The fundamental structure integrates terms representing natural growth/decay processes with intervention-induced effects:

Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) Systems: These represent the workhorse framework for most semi-mechanistic models, describing how system states evolve over time through rate equations [32]. In oncology, tumor growth dynamics are frequently captured using exponential, logistic, or Gompertz functions, while treatment effects are modeled through various "kill term" parameterizations [32]. For anti-infectives, microbial growth and antimicrobial-induced killing follow similar principles but with different parameter values and functional forms [33].

Key Model Components:

- System State Variables: Quantities representing biological entities (e.g., tumor volume, bacterial density, drug concentration)

- Growth Terms: Mathematical functions describing natural system expansion (e.g., exponential, logistic, or linear growth)

- Treatment Effect Terms: Functions quantifying intervention impacts (e.g., direct killing, growth inhibition)

- Transition Terms: Equations capturing conversions between system states (e.g., sensitive to resistant populations) [32]

Model Identification Approaches: Semi-mechanistic model development typically follows one of three strategies: (1) Bottom-up approaches building from first principles; (2) Top-down approaches fitting flexible functions to data; or (3) Middle-out strategies that incorporate known biology while keeping models identifiable from available data [31]. The middle-out approach has proven particularly valuable in complex domains like immuno-oncology, where some biological mechanisms are well-characterized while others remain incompletely understood [31].

Comparative Analysis of Growth and Decay Models

Table 1: Fundamental Growth Models in Biological Systems

| Model Type | Mathematical Formulation | Key Parameters | Biological Interpretation | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exponential Growth | dT/dt = k₉·T |

k₉: Growth rate constant | Unlimited growth proportional to current state | Early tumor growth [32]; Bacterial proliferation [33] |

| Logistic Growth | dT/dt = k₉·T·(1 - T/Tₘₐₓ) |

k₉: Growth rate; Tₘₐₓ: Carrying capacity | Density-limited growth accounting for resource constraints | Solid tumor dynamics [32] |

| Gompertz Growth | dT/dt = k₉·T·ln(Tₘₐₓ/T) |

k₉: Growth rate; Tₘₐₓ: Carrying capacity | Rapid early growth with progressive slowing | Established tumor growth with spatial constraints [32] |

| Linear Growth | dT/dt = k₉ |

k₉: Constant growth rate | Constant volume increase over time | Late-stage tumor growth [32] |

Table 2: Treatment Effect Models for Therapeutic Interventions

| Effect Model | Mathematical Formulation | Key Parameters | Mechanistic Interpretation | Therapeutic Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Order Kill | dT/dt = f(T) - k₄·T |

k₄: Kill rate constant | Cell killing proportional to population size | Constant concentration chemotherapy [32] |

| Exposure-Dependent Kill | dT/dt = f(T) - k₄·Exposure·T |

k₄: Drug potency parameter | Killing proportional to both population and drug exposure | PK-driven dosing regimens [32] |

| Resistance-Development | dT/dt = f(T) - k₄·e^(-λ·t)·Exposure·T |

k₄: Initial kill rate; λ: Resistance emergence rate | Progressive loss of efficacy due to resistance | Long-term antimicrobial or anticancer therapy [32] |

| Emax Model | k₉' = k₉·(1 - Eₘₐₓ·Exposure/(IC₅₀ + Exposure)) |

Eₘₐₓ: Maximal effect; IC₅₀: Potency | Saturable effect following Michaelis-Menten kinetics | Targeted therapies with receptor-mediated effects [32] |

Experimental Methodologies for Model Parameterization

In Vitro Systems for Anti-Infective Potency Assessment

Establishing quantitative relationships between drug exposure and biological effect requires carefully designed experimental systems that generate data for model parameterization:

Time-Kill Kinetics Studies: These experiments characterize the temporal dynamics of antimicrobial activity by monitoring bacterial density changes over time following antibiotic exposure [27]. Unlike static endpoints like minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), time-kill studies provide rich longitudinal data capturing both initial killing and potential regrowth due to resistance emergence or subpopulations [27]. Experimental protocols involve:

- Preparing standardized bacterial inoculums (typically 10⁵-10⁶ CFU/mL)

- Exposing cultures to fixed or dynamically changing antibiotic concentrations

- Sampling at predetermined timepoints (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours) for viable counting

- Quantifying concentration-dependent killing patterns and post-antibiotic effects [27]

Hollow Fiber Infection Models (HFIM): These advanced systems bridge the gap between static in vitro assays and in vivo models by simulating human pharmacokinetic profiles against bacterial populations [27]. HFIM technology enables:

- Simulation of human drug concentration-time curves

- Prolonged observation of bacterial responses to dynamically changing concentrations

- Assessment of resistance emergence under clinically relevant exposure scenarios [27]

- Evaluation of combination therapies through simultaneous administration of multiple agents [33]

Minimum Inhibitory/Bactericidal Concentration (MIC/MBC) Determinations: While providing limited dynamic information, MIC and MBC values serve as important anchoring points for model development [27]. Standardized protocols include:

- Broth microdilution methods with standardized media and inoculum sizes

- Endpoint reading after 18-24 hours incubation

- MBC determination through subculturing from clear wells

- Quality control using reference strains [27]

Figure 1: Integrated Experimental Workflow for Semi-Mechanistic Model Development - This diagram illustrates the sequential integration of in vitro characterization, pharmacokinetic profiling, and in vivo evaluation for comprehensive model parameterization and validation.

In Vivo Systems for Model Validation

Animal models provide critical data for validating semi-mechanistic models and establishing in vitro-in vivo correlations:

Immunocompetent Tumor Models: These systems capture complex immune-tumor interactions crucial for immuno-oncology applications [31]. The TC-1/A9 cold tumor model in C57BL/6J mice exemplifies this approach, featuring:

- Subcutaneous implantation of tumor cells expressing specific antigens

- Randomized treatment assignment when tumors reach predetermined sizes

- Longitudinal tumor volume measurements

- Immunophenotyping of tumor microenvironment [31]

Infection Model Systems: Animal models of bacterial, fungal, or viral infections enable assessment of antimicrobial efficacy under physiologically relevant conditions:

- Immunocompromised models for evaluating bacteriostatic vs. bactericidal activity

- Tissue-specific infection models (e.g., pneumonia, endocarditis, meningitis)

- Monitoring of pathogen density and host response biomarkers over time

- Assessment of combination therapy efficacy and resistance suppression [33]

Protocol Considerations: Standardized experimental protocols are essential for generating high-quality data for model parameterization:

- Consistent inoculum preparation and administration routes

- Controlled dosing regimens with documented pharmacokinetics

- Frequent sampling for longitudinal assessment of response markers

- Adequate group sizes for population variability assessment [31] [33]

Implementation Protocols for Key Model Types

Tumor Growth Inhibition (TGI) Modeling

The TGI framework represents one of the most widely applied semi-mechanistic approaches in oncology:

Base Structural Model:

Where:

- T = Tumor volume

- k₉ = First-order tumor growth rate

- k₄ = Drug-induced kill rate

- λ = Rate of resistance development

- Exposure = Drug concentration driving effect [32]

Implementation Protocol:

- Data Collection: Longitudinal tumor volume measurements from control and treated cohorts

- Structural Model Selection: Exponential, logistic, or Gompertz growth functions based on control group data

- Treatment Effect Parameterization: Direct kill, cytostatic, or resistance-development models

- Parameter Estimation: Nonlinear mixed-effects modeling to estimate population and individual parameters

- Model Validation: Visual predictive checks, bootstrap analysis, and external validation [32]

Case Example: In cold tumor models, TGI models have been extended to incorporate immune activation dynamics, with successful application to combinations including antigens, TLR-3 agonists, and immune checkpoint inhibitors [31].

Integrated PK/PD Modeling for Anti-Infectives

Semi-mechanistic PK/PD models quantitatively link antibiotic exposure to microbial killing: