Agar Well Diffusion Method: A Complete Guide to Antimicrobial Activity Screening

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the agar well diffusion method, a cornerstone technique for in vitro antimicrobial activity screening.

Agar Well Diffusion Method: A Complete Guide to Antimicrobial Activity Screening

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the agar well diffusion method, a cornerstone technique for in vitro antimicrobial activity screening. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles and scope of the method, delivers a detailed step-by-step protocol for its application, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and validates its use through comparative analysis with other established susceptibility testing methods. The content synthesizes current research and established standards to serve as a key resource for both novice and experienced practitioners in the field of antimicrobial discovery.

Understanding the Agar Well Diffusion Method: Principles and Scope

The agar well diffusion method is a foundational in vitro technique widely employed for the initial screening and evaluation of antimicrobial activity. Its principle is rooted in the diffusion of bioactive molecules through a solid growth medium to inhibit microbial growth. Within the broader context of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), a formidable global challenge, the quest for novel antimicrobial agents from both natural and synthetic sources has intensified [1]. In this relentless pursuit, reliable and accessible screening methods are pivotal. The agar well diffusion assay serves as a crucial first step in the discovery pipeline, providing researchers with a qualitative or semi-quantitative means to identify promising antimicrobial candidates from complex mixtures, such as plant extracts, microbial metabolites, or synthetic compound libraries [1] [2]. Its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and ability to handle numerous samples make it an indispensable tool in research laboratories, despite the development of more advanced technologies [1].

This application note delineates the core scientific principles of diffusion and zone of inhibition formation, provides a detailed protocol for conducting the assay, and offers guidance on data interpretation, specifically framed within antimicrobial activity screening research.

Core Principles and Theoretical Framework

The Diffusion Process

The agar well diffusion assay operates on the principle of passive diffusion. When a test compound, often in a liquid solution, is placed into a well punched into an agar plate, it creates a point source with a high concentration of the antimicrobial agent. A concentration gradient is established between the well and the surrounding agar. Driven by this gradient, the antimicrobial molecules move radially outward from the well through the water-filled pores of the agar gel matrix [3]. The rate and extent of this diffusion are governed by factors such as the molecular size, shape, and solubility of the antimicrobial agent, as well as the density and composition of the agar medium [4].

Formation of the Zone of Inhibition

The agar plate is uniformly inoculated with a standardized suspension of a test microorganism. As the antimicrobial agent diffuses, its concentration decreases with increasing distance from the well. After incubation, a clear, circular zone, known as the Zone of Inhibition (ZOI), becomes visible in the otherwise confluent lawn of microbial growth. This zone represents the area where the concentration of the diffused antimicrobial agent exceeds the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) required to prevent the visible growth of that specific microorganism [3]. The diameter of the ZOI is, therefore, a indirect measure of the antimicrobial potency of the test substance under the specific conditions of the assay; a larger zone typically indicates greater potency or a higher diffusion rate [2].

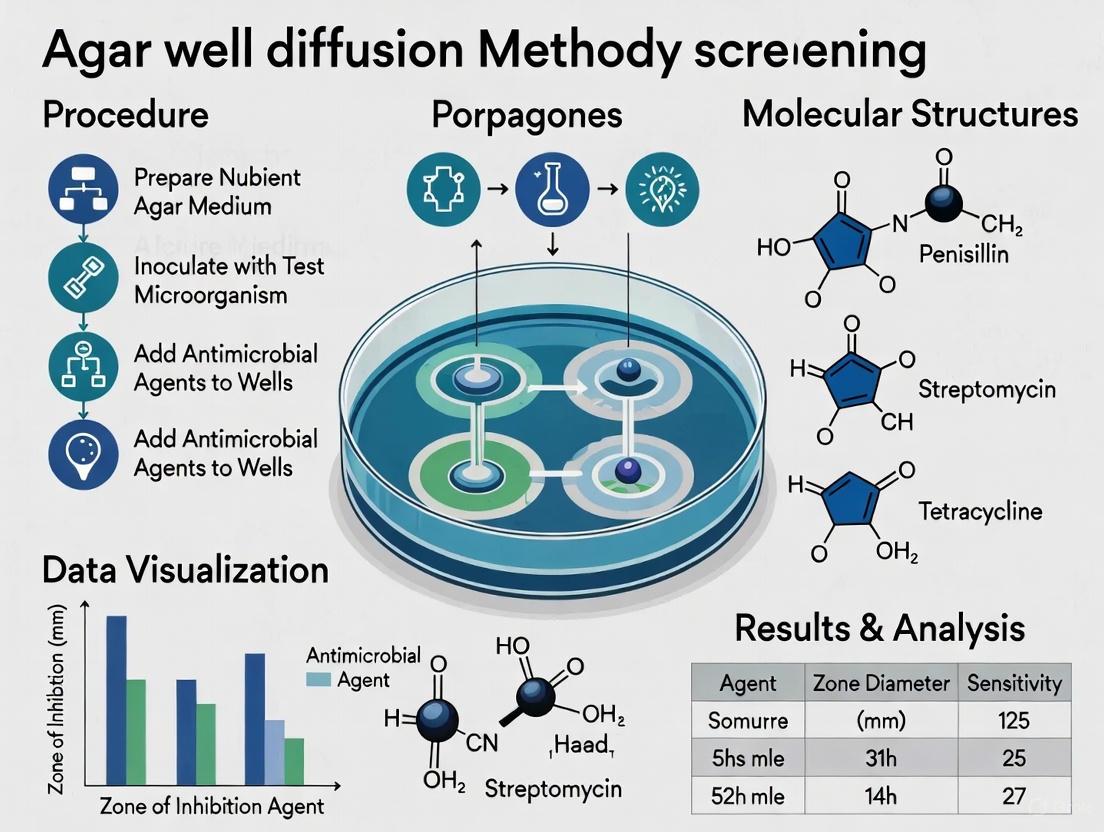

Figure 1: Workflow and Core Principles of the Agar Well Diffusion Assay. The diagram illustrates the sequential process from application of the antimicrobial agent into the well, its radial diffusion through the agar medium, to the final formation of the Zone of Inhibition (ZOI) based on the established concentration gradient relative to the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC).

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Materials and Reagents

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Agar Well Diffusion Assay

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) | Standardized growth medium for antibacterial testing [2] [5]. | Quality and composition (e.g., cation content, pH) can significantly impact results [5]. |

| Test Microorganism | Target pathogen (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923). | Use standardized, well-characterized strains from recognized culture collections [5]. |

| Sterile Saline or Broth | Preparation of standardized microbial inoculum. | Typically 0.85% saline or nutrient broth. |

| Cork Borer or Sterile Tip | Creation of uniform wells in the solidified agar. | Common diameters are 6-8 mm [6]. |

| Test Compound/Extract | The antimicrobial agent being evaluated. | Solubility and solvent choice (e.g., DMSO, water, ethanol) are critical and must be controlled for [5]. |

| Positive Control | Standard antibiotic (e.g., ampicillin, chloramphenicol). | Validates assay performance and provides a basis for comparison [6] [5]. |

| Negative Control | Solvent used to dissolve the test compound. | Ensures the solvent alone does not inhibit growth [5]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Preparation of Agar Plates: Pour sterilized and cooled Mueller-Hinton Agar (or other appropriate medium) into sterile Petri dishes on a level surface to achieve a uniform depth of approximately 4 mm. Allow the agar to solidify completely [2] [3].

Standardization of Inoculum: Prepare a microbial suspension in sterile saline or broth, adjusting the turbidity to match a 0.5 McFarland standard. This results in a suspension containing approximately 1-2 x 10^8 Colony Forming Units (CFU)/mL for bacteria [2].

Inoculation of Agar Plate: Using a sterile cotton swab, inoculate the entire surface of the agar plate uniformly with the standardized microbial suspension. Ensure confluent growth by swabbing in multiple directions [3].

Creation of Wells: Using a sterile cork borer or pipette tip, aseptically punch wells (typically 6-8 mm in diameter) into the solidified, inoculated agar. Carefully remove the agar plugs without damaging the well walls [6].

Application of Test and Control Substances: Using a sterile pipette, fill the wells with a precise volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) of the test compound, positive control, and negative control solutions. Avoid overfilling to prevent spillage.

Pre-diffusion and Incubation: Allow the plates to stand at room temperature or refrigerate for approximately 1 hour to enable pre-incubation diffusion of the substances into the agar. Subsequently, incub the plates in an inverted position at the optimal temperature for the test microorganism (e.g., 35±2 °C for many bacteria) for 16-24 hours [2] [3].

Measurement of Zones of Inhibition: After incubation, measure the diameter of the complete inhibition zones, including the well diameter, to the nearest millimeter using a caliper or ruler. The zone edge is defined by the point where visible growth starts [3].

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Quantitative Measurements and Reporting

The primary quantitative data from this assay is the diameter of the zone of inhibition. It is crucial to report the mean diameter from replicate experiments along with standard deviation or error. For a more precise assessment, some researchers calculate a corrected ZOI by subtracting the well diameter from the total measured zone diameter, which can help account for variations in sample volume or well size [3].

Table 2: Example of Quantitative Data from an Agar Well Diffusion Assay Using Onion Skin Extract [3]

| Concentration (mg/mL) | S. aureus (mm)* | E. coli (mm)* |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.33 ± 0.33 | 7.83 ± 0.17 |

| 5 | 8.17 ± 0.17 | 8.50 ± 0.29 |

| 10 | 8.83 ± 0.44 | 10.17 ± 0.44 |

| 25 | 10.83 ± 0.17 | 11.50 ± 0.29 |

| 50 | 11.67 ± 0.17 | 12.83 ± 0.44 |

| 100 | 14.17 ± 0.44 | 15.17 ± 0.60 |

| Positive Control | 24.50 ± 0.29 | 24.67 ± 0.44 |

| Negative Control | NIZ | NIZ |

NIZ: No Inhibition Zone

Limitations and Strategic Considerations

While highly valuable for screening, the agar well diffusion method has inherent limitations that researchers must consider when interpreting data and designing experiments:

- Qualitative/Semi-Quantitative Nature: The assay does not directly yield a Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) value, which is a more precise measure of antimicrobial potency [2]. It provides a relative comparison of potency between samples.

- Influence of Diffusibility: The size of the ZOI is a function of both antimicrobial efficacy and the compound's ability to diffuse through agar. A large molecule with strong antimicrobial activity may produce a small zone if it diffuses poorly, potentially leading to false negatives [4].

- Distinction of Cidal vs. Static Effects: A clear ZOI indicates inhibition of growth (bacteriostatic effect) but does not confirm microbial death (bactericidal effect). Subsequent tests, such as subculturing from the ZOI, are required to determine tidal activity [3].

- Standardization Challenges: For novel compounds, especially plant-derived polyphenols, there are no established interpretive criteria (breakpoints) to categorize microorganisms as susceptible or resistant, unlike for clinical antibiotics [5]. Results are typically compared to controls and reported as inhibition zone diameters.

Figure 2: Data Interpretation and Subsequent Steps. A decision pathway for analyzing Zone of Inhibition results and determining the appropriate follow-up experiments to validate and characterize antimicrobial activity.

The agar well diffusion method remains a cornerstone technique in the initial phases of antimicrobial discovery due to its simplicity, low cost, and high throughput capability. A deep understanding of the science of diffusion and zone of inhibition is paramount for designing robust experiments and interpreting results accurately. While it provides an excellent first-pass screening tool, its findings should often be supplemented with more quantitative methods, such as broth microdilution for MIC determination, to fully characterize the potency and mechanism of promising antimicrobial agents in the fight against drug-resistant pathogens [1] [2].

The agar well diffusion method is a cornerstone technique in antimicrobial activity screening, prized for its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and ability to handle diverse sample types. This method is vital for researchers combating the global threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), providing a foundational tool for discovering new therapeutic agents from natural and synthetic sources [1] [2]. Its principle relies on the diffusion of test compounds from a reservoir (a well cut into the agar) into the surrounding medium, which is seeded with a test microorganism. The resulting zone of inhibition around the well provides a qualitative measure of antimicrobial potency [6] [1].

This application note details the core protocols and specific applications of the agar well diffusion method, framing it within the essential workflow of modern antimicrobial discovery.

Core Protocol: Agar Well Diffusion Method

The following section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for performing the agar well diffusion assay.

The diagram below illustrates the generalized experimental workflow for the agar well diffusion method.

Detailed Materials and Methodology

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 1: Essential materials and reagents for the agar well diffusion assay.

| Item | Function/Description | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) | A standardized, non-selective medium recommended for antibacterial susceptibility testing by CLSI [2] [7]. | Commercially available dehydrated powder; prepared according to manufacturer instructions. |

| Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) | A common medium used for determining antifungal activity [6]. | Commercially available dehydrated powder. |

| Sterile Cork Borer | For creating uniform wells in the solidified agar medium [6]. | Typically 5-8 mm in diameter; sterilized by autoclaving or flaming. |

| 0.5 McFarland Standard | A reference standard to adjust the turbidity of the microbial inoculum to approximately 1-2 x 10^8 CFU/mL [2] [7]. | Commercially available suspension or prepared in-house. |

| Sterile Swabs | For creating a uniform bacterial lawn on the surface of the agar medium [6] [7]. | Cotton or synthetic tipped. |

| Positive Control (Antibiotic Discs) | Standardized controls to validate the assay performance (e.g., Ampicillin, Chloramphenicol) [6]. | Commercially available discs with known potency. |

| Negative Control (Solvent) | Control for any antimicrobial activity from the sample solvent (e.g., distilled water, phosphate buffer) [7]. | Matches the solvent used to prepare the test sample. |

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Preparation of Inoculum: Fresh overnight broth cultures of the test microorganisms (bacterial/fungal pathogens) are prepared. The turbidity of the suspension is adjusted to match a 0.5 McFarland standard, which corresponds to approximately 1-2 x 10^8 Colony Forming Units (CFU)/mL for bacteria [2] [7].

- Inoculation of Agar Plates: The surface of sterile Mueller Hinton Agar (for bacteria) or Potato Dextrose Agar (for fungi) plates is inoculated by spreading the standardized microbial suspension evenly with a sterile cotton swab [6] [7].

- Well Creation: Using a sterile cork borer or tip, uniform wells (typically 5-8 mm in diameter) are aseptically punched into the inoculated agar [6] [7].

- Sample Introduction: A defined volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) of the test sample (e.g., bacterial culture supernatant, plant extract, probiotic suspension) is introduced into the respective wells using a sterile pipette. Appropriate positive (standard antibiotics) and negative (solvent) controls are included [6] [7].

- Pre-Diffusion and Incubation: The plates are left at room temperature for about 1 hour to allow for pre-diffusion of the sample into the agar. Subsequently, the plates are incubated at the optimal temperature for the test microorganism (e.g., 37°C for 24 hours for most human bacterial pathogens) [6].

- Analysis: After incubation, the diameters of the clear zones of inhibition (ZOI) surrounding the wells are measured in millimeters using a caliper or ruler. The ZOI indicates the concentration gradient of the antimicrobial agent and its effectiveness in inhibiting the growth of the test microorganism [6] [2].

Key Applications and Protocols

The agar well diffusion method is highly versatile. The table below summarizes its key applications, and subsequent sections provide specific experimental contexts.

Table 2: Key applications of the agar well diffusion method in antimicrobial research.

| Application Area | Test Sample | Target Pathogens | Key Findings/Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotic Screening | Cell-free metabolites, culture supernatants, or whole cells of probiotic strains like Lactobacillus plantarum [7]. | Food-borne pathogens (E. coli, S. aureus, Salmonella spp.) [7]. | Zones of inhibition (10-30 mm) demonstrate probiotic strain's antibacterial potential and utility in combating multi-drug resistant (MDR) bacteria [7]. |

| Natural Product Discovery | Extracts from Actinobacteria, plants, or fermented products (e.g., curd whey) [6] [7]. | Human, shrimp, and fungal pathogens [6]. | Rapid primary screening of a large number of extracts or fractions to identify promising antimicrobial leads [6] [8]. |

| Synergistic Studies | Combination of a probiotic supernatant or natural extract with a standard antibiotic [7]. | MDR clinical isolates [7]. | A remarkable increase in the zone diameter indicates a synergistic effect, offering strategies to rejuvenate the efficacy of existing antibiotics [7]. |

Application Note 1: Screening Probiotic Antimicrobial Activity

Objective: To evaluate the antibacterial potential of commercially available probiotic formulations against common food-borne pathogens.

Protocol Modifications:

- Test Samples: Probiotic granules or powders are dissolved/suspended in sterile distilled water or appropriate buffer [7].

- Pathogens: Use freshly cultured food-borne pathogens such as Escherichia coli, Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Salmonella typhi [7].

- Controls: Use standard antibiotic discs as positive controls and the suspension solvent as a negative control.

- Analysis: Measure and compare the ZOIs. The results can be confirmed and quantified further by determining the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) using broth microdilution techniques [7].

Application Note 2: Evaluating Natural Product Extracts

Objective: To screen Actinobacteria isolates for the production of antimicrobial compounds.

Protocol Modifications:

- Test Samples: Cell-free culture supernatants or organic solvent extracts of Actinobacteria strains grown in various production media [6] [8].

- Pathogens: A panel of Gram-positive, Gram-negative bacteria, and fungi can be used to determine the spectrum of activity [6].

- Specifics: Nutrient agar is typically used for antibacterial activity, while Potato Dextrose Agar is used for antifungal activity [6].

- Analysis: The inhibition zones of different Actinobacteria strains (e.g., AVVM1 to AVVM11) are compared to each other and to standard antibiotics to identify the most potent producers [6].

Application Note 3: Assessing Synergistic Effects

Objective: To investigate the synergistic interaction between a natural product (e.g., probiotic supernatant) and a conventional antibiotic against a multi-drug resistant pathogen.

Protocol Modifications:

- Experimental Setup: The assay is performed as described in the core protocol.

- Test Groups: Include wells for (a) the natural product alone, (b) the antibiotic alone (can be a disc placed adjacent to the well), and (c) a well containing the combination of both agents.

- Analysis: Synergy is indicated by a significant increase in the zone of inhibition in the combination group compared to the zones produced by each agent individually. The effect can be quantified by calculating the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index through checkerboard broth microdilution assays for validation [7].

Advantages and Limitations

Advantages:

- Simplicity and Low Cost: The method is technically straightforward and requires no specialized equipment, making it accessible for most laboratories [1] [2].

- High-Throughput Potential: It is suitable for the initial screening of a large number of samples, such as microbial isolates or plant extracts [2] [8].

- Flexibility: It can be applied to a wide range of sample types, including turbid or insoluble materials that are not suitable for disk diffusion assays [1].

Limitations:

- Qualitative/Semi-Quantitative: The method does not directly provide a Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) value, as the ZOI is influenced by the diffusion rate of the compound in agar [2].

- Diffusion Dependency: The size of the inhibition zone is affected by the molecular weight, charge, and hydrophobicity of the antimicrobial agent, which can bias results [2].

- Cannot Distinguish Bacteriostatic vs. Bactericidal Effects: The zone of inhibition indicates growth inhibition but does not confirm whether the effect is reversible (bacteriostatic) or lethal (bactericidal) [2].

The agar well diffusion method remains an indispensable tool in the initial stages of antimicrobial discovery. Its robust and adaptable nature allows researchers to efficiently screen probiotics, natural product extracts, and synthetic compounds for bioactive potential. While its qualitative nature is a limitation, it serves as an excellent primary filter. For comprehensive characterization, results from the well diffusion assay should be followed by quantitative methods like broth microdilution to determine MICs and time-kill kinetics to establish the nature of the antimicrobial activity [1] [2]. In the relentless fight against antimicrobial resistance, this classic technique continues to provide a solid foundation for identifying the next generation of antimicrobial agents.

The agar well diffusion method is a cornerstone technique for the initial screening and evaluation of antimicrobial activity in research and development. Its principle relies on the diffusion of an antimicrobial agent from a reservoir (a well cut into the agar) into the surrounding medium, which has been seeded with a test microorganism. The resulting zone of inhibition around the well is a measurable indicator of antimicrobial efficacy [6] [2]. As antibiotic resistance continues to pose a formidable global challenge, the drive to discover novel antimicrobial agents from natural and synthetic sources has intensified, underscoring the critical need for robust and standardized screening methods [1]. This document outlines the essential requirements for media, test organisms, and quality control strains to ensure the reliability, reproducibility, and accuracy of data generated using the agar well diffusion method within a rigorous research context.

Media Requirements

The selection of an appropriate growth medium is paramount, as it must support robust growth of the test microorganism while allowing for optimal diffusion of the antimicrobial substance. Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) is the most recommended and widely used medium for antibacterial testing due to its well-documented reproducibility, low antagonism, and compliance with standards set by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [9] [2]. For specific fastidious bacteria or antifungal activity screening, the medium may require modification or substitution.

Table 1: Standard Media for Agar Well Diffusion Assays

| Microorganism Type | Standard Medium | Specific Modifications/Alternatives | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-fastidious Bacteria | Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) | None | Standardized testing for reproducible results [2] |

| Fastidious Bacteria | Supplemented MHA | As specified by CLSI/EUCAST standards | Supports growth of pathogens like Streptococci and Haemophilus influenzae [2] |

| Fungi/Yeast | Mueller-Hinton Agar + 2% Glucose + 0.5μg/mL Methylene Blue (MHA+GMB) | Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) | Enhances detection of antifungal activity; PDA is commonly used for molds and fungi [6] [2] |

| General Screening | Nutrient Agar | Potato Dextrose Agar | Commonly used in screening studies for antibacterial and antifungal activity, respectively [6] |

Test Organisms

A well-characterized and standardized panel of test microorganisms is crucial for comprehensive antimicrobial screening. This panel should include representative strains of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, as well as fungi, to determine the spectrum of activity. Researchers often utilize reference strains obtained from international culture collections, such as the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), to ensure consistency and allow for cross-study comparisons [9].

Table 2: Representative Test Organisms for Antimicrobial Screening

| Category | Example Species | Reference Strain Example | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-Positive Bacteria | Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Bacillus cereus | S. aureus ATCC 25923 | Common pathogens; models for antibiotic resistance [6] [9] |

| Gram-Negative Bacteria | Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, Klebsiella pneumoniae | E. coli ATCC 25922 | Models for outer membrane permeability and efflux mechanisms [6] [9] |

| Fungi/Yeast | Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis | C. albicans ATCC 2091 | Common models for antifungal susceptibility testing [9] |

| Animal Pathogens | Pasteurella multocida, Mannheimia haemolytica | Specific serovars | Relevant for veterinary drug development [10] |

Quality Control Strains

Incorporating quality control (QC) strains into every assay run is non-negotiable for validating experimental conditions and ensuring data integrity. QC strains have well-defined susceptibility profiles and are used to monitor the precision and accuracy of the technical procedures. The zone of inhibition diameters obtained for these strains should fall within established published ranges [2].

Table 3: Essential Quality Control Strains

| QC Strain | Standard Media | Typical Use | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | Mueller-Hinton Agar | Antibacterial assay control | Verifies medium performance and diffusion characteristics for Gram-negative bacteria [2] |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 | Mueller-Hinton Agar | Antibacterial assay control | Verifies medium performance and diffusion characteristics for Gram-positive bacteria [2] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | Mueller-Hinton Agar | Antibacterial assay control | Particularly important for testing diffusion of larger molecules or nanoparticles [9] |

| Candida albicans ATCC 90028 | MHA + GMB or PDA | Antifungal assay control | Monitors performance of media and conditions for yeast testing [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Agar Well Diffusion Method

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the agar well diffusion protocol:

Step-by-Step Procedure

Preparation of Agar Plates

- Prepare the appropriate medium (e.g., Mueller-Hinton Agar) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Autoclave to sterilize and pour approximately 20-25 mL into each sterile Petri dish on a level surface to ensure uniform thickness. Allow the agar to solidify completely at room temperature [2].

Standardization of Inoculum

- Prepare a fresh broth culture of the test or QC organism and incubate until it reaches the mid-logarithmic phase of growth (typically 3-5 hours).

- Adjust the turbidity of the bacterial suspension to a 0.5 McFarland standard, which is equivalent to approximately 1-2 x 10^8 Colony Forming Units (CFU)/mL [2]. For fungal suspensions, adjust to 1.0 McFarland standard [9].

Inoculation of Agar Surface

- Within 15 minutes of adjusting the turbidity, dip a sterile cotton swab into the standardized suspension.

- Rotate the swab firmly against the inside of the tube to remove excess fluid.

- Swab the entire surface of the agar plate thoroughly in three directions (rotating the plate approximately 60° each time) to ensure a confluent "lawn" of growth [2].

Creation of Wells

Loading of Test Samples

- Using a sterile pipette, add a precise volume (typically 60-100 µL) of the test sample, positive control (standard antibiotic), and negative control (solvent alone) into their respective wells [6].

- Allow the plates to stand for a pre-incubation diffusion period at room temperature or in a refrigerator for about 1 hour to allow the agent to diffuse into the agar [6].

Incubation

- Invert the plates and incubate them at the optimal temperature for the test microorganism (35±2°C for most human pathogens) for 16-24 hours [2].

Measurement of Zones of Inhibition

Quality Control Verification

- For the assay to be considered valid, the zone diameters for the QC strains must fall within the acceptable ranges published by CLSI or EUCAST for the positive control antibiotics used [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful agar well diffusion assay depends on the consistent quality of its core components. The following table details the essential materials required.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Specification / Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mueller-Hinton Agar | Dehydrated powder or prepared plates. Provides a standard medium for reproducible bacterial growth and antimicrobial diffusion [2]. | The gold standard for non-fastidious bacteria. Must be prepared with strict pH control (pH 7.2-7.4). |

| 0.5 McFarland Standard | A barium sulfate suspension used as a visual reference to standardize microbial inoculum density to ~1.5 x 10^8 CFU/mL [2]. | Essential for achieving a confluent lawn. Can be replaced with a densitometer for higher precision. |

| Sterile Cork Borer | A metal borer, typically 6 mm in diameter, for creating uniform wells in the agar [6] [10]. | Ensures consistent well size, which is critical for the reproducibility of zone diameters. |

| Quality Control Strains | Certified reference strains (e.g., E. coli ATCC 25922, S. aureus ATCC 25923) with defined susceptibility profiles [2]. | Must be used in every run to validate the entire testing process, from media to incubation. |

| Standard Antibiotic Disks/Solutions | Known antibiotics (e.g., ampicillin, chloramphenicol) used as positive controls for comparison and QC purposes [6]. | Allows for result comparison across different experiments and laboratories. |

| Solvent Controls | The solvent used to dissolve the test compound (e.g., DMSO, methanol, water). Serves as a negative control [10]. | Critical for confirming that any observed activity is from the test agent and not the solvent. |

Advantages and Inherent Limitations of the Diffusion-Based Approach

Agar well diffusion is a foundational technique in antimicrobial activity screening, widely employed for its simplicity and cost-effectiveness in research and early-stage drug discovery [1] [6]. This method belongs to a broader family of agar diffusion assays, which are based on the principle that an antimicrobial agent diffuses from a reservoir into a solid growth medium seeded with a test microorganism [2] [8]. The resulting zone of inhibition around the reservoir provides a visual and measurable indicator of antimicrobial potency [1]. Within the context of screening novel antimicrobial agents—from plant extracts to synthetic compounds and nanoparticles—this method serves as a valuable initial tool for identifying promising candidates [1] [8]. However, a comprehensive understanding of its principles, advantages, and, crucially, its inherent limitations is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to accurately interpret data and make informed decisions on subsequent testing strategies [11] [12]. This application note details the core principles, advantages, and limitations of the diffusion-based approach, providing a standardized protocol for its implementation in antimicrobial screening research.

Core Principles and Key Advantages

The fundamental principle of the agar well diffusion method involves the creation of a concentration gradient of the antimicrobial substance in an agar matrix. When a test compound is placed into a well punched into the agar, it diffuses radially outward into the medium, which has been uniformly inoculated with a test microorganism [1] [2]. After incubation, the growth of the microorganism becomes visible, except in the circular area around the well where the concentration of the diffused compound exceeded the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) for that specific strain. The diameter of this clear zone of inhibition is inversely related to the MIC under standardized conditions [2].

The widespread adoption of this method is attributed to a compelling set of practical advantages, particularly for screening purposes.

Table 1: Key Advantages of the Agar Well Diffusion Method

| Advantage | Description |

|---|---|

| Simplicity and Low Cost | The technique is straightforward to perform and does not require sophisticated or expensive instrumentation. The consumables, such as agar plates and cork borers, are inexpensive [1] [2] [13]. |

| High-Throughput Screening | It allows for the simultaneous testing of multiple samples or extracts against one or more microbial targets on a single plate, facilitating rapid initial screening [2] [8]. |

| Visual and Qualitative Results | The zone of inhibition provides an immediate, visual readout of antibacterial activity, making it easy to identify potent samples [6] [8]. |

| Minimal Equipment Requirements | Unlike broth microdilution or advanced techniques like flow cytometry, it can be performed in laboratories with basic microbiological setup [1] [2]. |

The experimental workflow for conducting an agar well diffusion assay involves a series of standardized steps to ensure reproducibility, from plate preparation to data analysis.

Figure 1: Agar Well Diffusion Experimental Workflow

Critical Limitations and Challenges

Despite its utility for qualitative screening, the agar well diffusion method possesses significant inherent limitations that restrict its quantitative application and demand careful consideration.

Physicochemical and Quantitative Limitations

The most critical limitation revolves around the diffusion process itself. The size of the inhibition zone is not solely determined by the antimicrobial potency of the sample but is also profoundly influenced by the diffusibility of the active compound(s) through the aqueous agar matrix [11]. Molecules with high lipophilicity or low water-solubility will not diffuse effectively, leading to disproportionately small or non-existent zones of inhibition even if the sample possesses strong intrinsic antimicrobial activity [11] [12]. This makes the method poorly suited for evaluating non-polar extracts, essential oils, or certain plant-derived compounds [11]. Furthermore, the method is considered primarily qualitative, as it does not directly provide a Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) value, which is the gold-standard quantitative measure of antimicrobial activity [2] [11]. While approximate MICs can be estimated using algorithms, these are not as accurate as values obtained from dilution methods [2].

Standardization and Reproducibility Challenges

Achieving reproducible results between different laboratories is notoriously difficult with diffusion-based methods due to the multitude of variables that must be rigorously controlled [11] [12].

Table 2: Key Variables Affecting Reproducibility in Well Diffusion Assays

| Variable | Impact on Results |

|---|---|

| Inoculum Density | Higher inoculum sizes can lead to smaller zones of inhibition and potentially false-negative results [2] [12]. |

| Agar Thickness & Depth | Variations affect the diffusion distance and volume of medium, directly influencing the zone size [11]. |

| Pre-incubation Diffusion Time | The time allowed for the compound to diffuse into the agar before incubation (often in a refrigerator) must be standardized [11]. |

| Culture Medium Composition | The nutrient content can affect both microbial growth and the diffusion characteristics of the antimicrobial agent [11] [12]. |

| Solvent Effects | Solvents like DMSO or ethanol used to dissolve samples can themselves inhibit growth or affect diffusion, requiring careful negative controls [12]. |

The interplay of these factors creates a complex relationship that is visualized in the following diagram, highlighting why zone size is an imperfect proxy for pure antimicrobial potency.

Figure 2: Factors Influencing the Zone of Inhibition

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Agar Well Diffusion Assay

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Agar Well Diffusion Assay

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) | The non-fastidious recommended medium for antibacterial testing against non-fastidious bacteria. For fungi, Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) or other specific media are used [6] [2]. |

| Standardized Microbial Inoculum | Test organisms adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard (approximately 1-2 x 10^8 CFU/mL for bacteria) in a saline solution [2] [13]. |

| Sterile Cork Borer or Tip | For creating uniform wells (typically 5-8 mm in diameter) in the solidified agar [6]. |

| Positive Control | A known antibiotic (e.g., ampicillin, chloramphenicol) to validate the assay conditions and serve as a reference [12]. |

| Negative Control | The solvent used to dissolve the test sample (e.g., water, DMSO, ethanol) to confirm it does not inhibit growth [12]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Preparation of Inoculated Agar Plates: Melt and cool Mueller-Hinton Agar (or other appropriate medium) to approximately 45-50°C. Inoculate the sterile molten agar with a standardized microbial suspension (e.g., 0.5 McFarland standard), mix gently but thoroughly, and pour into sterile Petri dishes to achieve a uniform depth of approximately 4 mm. Allow the agar to solidify completely at room temperature [2] [13].

- Creation of Wells: Using a sterile cork borer or pipette tip, aseptically punch wells (typically 6-8 mm in diameter) into the solidified agar. Carefully remove the agar plugs without tearing the medium. A typical plate can accommodate 4-6 wells in a circular pattern [6].

- Application of Test Samples: Pipette a precise volume (typically 50-100 µL) of the test sample, positive control, and negative control solution into separate, labeled wells. Ensure the solution does to not overflow the well [6] [14].

- Pre-incubation Diffusion: Place the plates in a refrigerator (approx. 4°C) for 1-2 hours. This pre-incubation period is critical as it allows the test compound to diffuse into the agar before microbial growth begins, leading to a sharper zone edge [11].

- Incubation: Transfer the plates to an incubator set at the optimal temperature for the test microorganism (e.g., 37°C for many human pathogens) for 16-24 hours (or as required for the specific organism). Incubate the plates in an inverted position to prevent condensation from dripping onto the agar surface [2].

- Measurement and Analysis: After incubation, measure the diameter of the zones of inhibition (including the well diameter) to the nearest millimeter using a caliper or ruler. The zone is defined as the area showing no visible growth. Record the measurements for all samples and controls [2] [13].

The agar well diffusion method remains a valuable tool in the initial stages of antimicrobial screening due to its simplicity, low cost, and ability to handle multiple samples efficiently [1] [2]. It provides an excellent first-pass method for identifying crude extracts or compounds with antimicrobial potential. However, researchers must be acutely aware of its inherent limitations, particularly its qualitative nature, poor suitability for non-polar compounds, and susceptibility to experimental variables that can compromise reproducibility and quantitative analysis [11] [12]. Consequently, results from agar well diffusion assays should be considered preliminary. Promising candidates identified through this method must be subjected to more quantitative techniques, such as broth microdilution for MIC determination and time-kill kinetics studies, to fully characterize their antimicrobial efficacy and potential for further development [2] [11].

Executing the Assay: A Standardized Step-by-Step Protocol

Within the framework of research aimed at screening for novel antimicrobial agents, the agar well diffusion method stands as a fundamental, reliable, and widely used technique for the initial evaluation of antimicrobial activity [2]. Its principle relies on the diffusion of a test substance from a reservoir (a well) into a solidified agar medium that has been seeded with a test microorganism. The subsequent formation of a zone of inhibition around the well provides a qualitative and semi-quantitative measure of the compound's ability to suppress microbial growth [6]. The reproducibility and accuracy of this entire assay are critically dependent on the initial, meticulous preparation of the agar plates and a standardized test inoculum [15]. This protocol details these essential first steps, which form the foundation for any robust antimicrobial screening program.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the essential materials and reagents required for the preparation of agar plates and test inoculum.

Table 1: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Specification / Function |

|---|---|

| Agar Powder | A gelling agent derived from seaweed, forming a solid matrix for microbial growth. Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) is the standard for non-fastidious bacteria [15]. |

| Nutrient Medium | Provides essential nutrients for microbial growth. Common choices include Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) for inoculum preparation and MHA for plates [15]. |

| Sterile Distilled Water | Solvent for preparing agar and broth solutions [16]. |

| Antimicrobial Agent (Standard) | A known antibiotic solution (e.g., at 1000x concentration) for use as a positive control and for quality assurance [16]. |

| Test Microorganism | A standardized, pure culture of the target bacterium (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923) or fungus [15]. |

| Saline Solution (0.85% NaCl) | A sterile isotonic solution used for making bacterial suspensions and dilutions [17]. |

| McFarland Standard | A reference suspension used to standardize the turbidity (and thus the approximate cell density) of the bacterial inoculum [15]. The 0.5 McFarland standard is equivalent to ~1-2 x 10⁸ CFU/mL for bacteria [2]. |

Equipment

- Autoclave

- Water Bath (45-50°C)

- Laminar Flow Hood

- Bunsen burner

- Sterile Petri dishes (e.g., 90-100 mm diameter)

- Sterile pipettes and micropipettes

- Sterile swabs

- Vortex mixer

- Spectrophotometer (optional, for inoculum standardization)

- Incubator

Protocol

Preparation of Agar Plates

The following workflow outlines the key steps involved in preparing Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) plates, the recommended medium for routine antibacterial susceptibility testing [15].

Detailed Procedure:

- Weighing and Suspension: Weigh the appropriate amount of Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) powder. A typical preparation uses 37-38 grams per liter of distilled water [16]. Transfer the powder to an autoclavable flask and add the required volume of sterile distilled water. Swirl to form a suspension.

- Sterilization: Loosely cover the flask (with a cap or aluminum foil) and sterilize the mixture using an autoclave at 121°C and 15-20 psi for at least 30 minutes [16] [18].

- Cooling: After autoclaving, carefully remove the flask and place it in a water bath set to 45-50°C. Allow the agar to cool until the flask is comfortable to hold with bare hands. This temperature is low enough to prevent the formation of excessive condensation on the plate lids but high enough to keep the agar in a liquid state [16] [18].

- Pouring Plates: Working aseptically in a laminar flow hood or near a Bunsen burner, pour approximately 20-25 mL of the molten agar into each sterile Petri dish [18]. Pour steadily to avoid creating air bubbles. If adding specific antibiotics or test compounds, this is the stage to add them to the cooled agar and mix thoroughly before pouring.

- Solidification and Storage: Leave the plates undisturbed on a level surface until the agar has completely solidified (approximately 30 minutes). For best results, allow the plates to dry further by incubating them upright at room temperature overnight before use. Plates can be stored sealed in plastic bags at 4°C for several weeks [16].

Preparation of Test Inoculum

Standardizing the density of the microbial inoculum is arguably the most critical factor for achieving reproducible and comparable results in the agar well diffusion assay [15]. The goal is to achieve a confluent "lawn" of growth.

Table 2: Inoculum Standardization Guide

| Microorganism Type | Growth Medium | Incubation Conditions | Target Inoculum Density (CFU/mL) | Standardization Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-fastidious Bacteria (e.g., E. coli, S. aureus) | Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) | 35±2°C for 18-24 hours [2] | 1 x 10⁸ [15] | 0.5 McFarland Standard [15] |

| Fastidious Bacteria (e.g., S. pneumoniae) | Enriched Broth (e.g., MHB with blood) | 35±2°C in CO₂ for 18-24 hours [2] | 1 x 10⁸ | 0.5 McFarland Standard |

| Yeasts (e.g., C. albicans) | Sabouraud Dextrose Broth or RPMI 1640 | 35±2°C for 24-48 hours [2] | 1 x 10⁶ to 5 x 10⁶ [2] | 0.5 McFarland Standard (approximate) |

Detailed Procedure (Direct Colony Suspension Method):

- Select Colonies: From a fresh (18-24 hour) agar plate culture, select 3-5 well-isolated colonies of the test microorganism [15].

- Prepare Suspension: Transfer the selected colonies into a tube containing 4-5 mL of sterile saline or MHB.

- Vortex: Vortex the tube vigorously to achieve a homogeneous bacterial suspension.

- Standardize Density: Adjust the turbidity of the suspension to match that of a 0.5 McFarland standard. This is done by comparing the turbidity of the suspension tube against the McFarland standard tube against a card with contrasting lines. Add more bacteria or saline diluent until the turbidity is equivalent [15].

- Use Inoculum: This standardized suspension must be used within 15-30 minutes of preparation to prevent significant changes in bacterial concentration [15].

Quality Control and Troubleshooting

- Positive Control: Always include a well with a known, standard antimicrobial agent on every plate to verify that the test system is functioning correctly and the microorganism is behaving as expected [16].

- Negative Control: Include a well with only the solvent used to dissolve the test compound to rule out any antimicrobial activity from the solvent itself.

- Lawn Check: After inoculation and incubation, the control plate (without any test compounds) should show confluent growth. Discrete, individual colonies indicate an insufficient inoculum density, while an overly heavy growth may impede diffusion.

- Common Issues:

- No zones in positive control: Likely an issue with the inoculum being too dense, the antimicrobial agent being degraded, or incorrect incubation.

- Uneven or slanted zones: Caused by uneven agar thickness or a non-level surface during solidification and incubation.

- No growth on the plate: The inoculum was non-viable or the agar contains inhibitory substances.

The agar well diffusion assay is a fundamental technique for the preliminary screening and evaluation of antimicrobial activity in various substances, including plant extracts, essential oils, synthetic compounds, and nanoparticles [1]. This method is highly valued in research and drug development for its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and ability to provide rapid, visual results concerning the inhibitory potential of test materials against microbial targets [2] [1]. The creation of wells and the subsequent application of test samples represent a critical phase in this protocol. The accuracy and precision exercised during this step are paramount, as they directly influence the diffusion characteristics of the antimicrobial agent and, consequently, the reliability and reproducibility of the resulting zones of inhibition [12]. This document provides a detailed, standardized protocol for this crucial procedure, framed within the context of antimicrobial activity screening research.

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for the agar well diffusion method, with the focal steps of this protocol highlighted.

Figure 1: The complete workflow for the agar well diffusion assay, highlighting the key steps of well creation and sample application.

Research Reagent Solutions

The successful execution of the agar well diffusion assay relies on a set of essential materials and reagents. The table below details these key components and their specific functions within the protocol.

Table 1: Essential materials and reagents for the agar well diffusion assay.

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) | The standard non-selective solid growth medium recommended by CLSI and EUCAST for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. It provides a clear background for visualizing zones of inhibition [15] [19]. |

| Test Samples/Supernatants | The solutions being investigated for antimicrobial activity. These can include plant extracts, microbial culture supernatants, essential oils, synthetic compounds, or nanoparticle suspensions [1] [9]. |

| Appropriate Solvents | Vehicles for dissolving or diluting test samples. Common choices include sterile water, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), methanol, ethanol, and acetone. The solvent must not possess antimicrobial activity at the concentration used, and a solvent control is mandatory [12]. |

| Positive Control (Antibiotic) | A standard antibiotic solution of known potency and concentration. This verifies the susceptibility of the test microorganism and the overall performance of the assay [12]. |

| Negative Control (Solvent) | The pure solvent used to dissolve the test sample. This confirms that any observed zone of inhibition is due to the sample and not the solvent [12]. |

| Sterile Well Borer | A sterile cork borer, glass tube, or tip of uniform diameter (typically 6-8 mm) used to punch wells into the solidified agar in an aseptic manner [9] [8]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 2A: Creating Wells in the Agar

After the agar plates have been inoculated with the standardized microbial suspension and the lawn has dried, proceed to create the wells.

Table 2: Step-by-step protocol for creating wells in the agar.

| Step | Procedure | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Select Equipment | Use a sterile cork borer, stainless steel tube, or pipette tip with a uniform diameter of 6 to 8 mm [9]. | A consistent bore diameter is crucial for the reproducibility of zone sizes. |

| 2. Punch Wells | Using aseptic technique, punch wells into the solidified, inoculated agar. Gently remove the agar plug using a sterile instrument without gouging the base of the plate. | Ensure the well is cleanly cut and the bottom of the well is sealed to the agar surface to prevent sample leakage. |

| 3. Well Arrangement | Space wells evenly, with a minimum distance of 20-30 mm between the centers of adjacent wells and from the edge of the plate. | Adequate spacing prevents overlapping zones of inhibition, allowing for accurate measurement [19]. |

| 4. Final Check | Inspect each well to ensure its integrity. If the well is damaged, the plate should be discarded and the process repeated. |

Step 2B: Applying Test Samples/Supernatants

Immediately after well creation, the test samples and controls are applied.

Table 3: Step-by-step protocol for applying test samples and supernatants.

| Step | Procedure | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Prepare Samples | Ensure test samples and controls are at the desired concentration and properly dissolved or suspended. For quantitative assessment, serial dilutions can be tested [1]. | Sample viscosity and solubility can affect diffusion; ensure a homogenous solution/suspension [12]. |

| 2. Pipette into Wells | Using a micropipette, carefully fill each well with a precise volume of the test sample, control, or supernatant. A typical volume is 50-100 µL, depending on the well's capacity [9]. | Do not overfill or spill the sample onto the surface of the agar, as this will distort the zone of inhibition. |

| 3. Sample Allocation | Apply the negative control (solvent) to at least one well and the positive control (standard antibiotic) to another. Apply test samples to the remaining wells. | Proper controls are non-negotiable for validating the assay results [12]. |

| 4. Pre-diffusion (Optional) | Allow the plate to stand at room temperature for 1-2 hours for the sample to pre-diffuse into the agar. This can lead to more concentric zones. | If performed, ensure the plate is placed on a flat, level surface. |

| 5. Incubation | Invert the plates and incubate under conditions suitable for the test microorganism (e.g., 35±2 °C for 16-18 hours for many bacteria) [2] [15]. | Incubation times may vary for fastidious organisms or fungi [2]. |

Quality Control and Troubleshooting

Ensuring the validity of the results requires rigorous quality control and an understanding of potential issues.

Table 4: Common challenges and troubleshooting guidelines for Step 2.

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uneven or irregular zones | Wells punched too close together; sample spilled on agar surface; uneven agar surface. | Maintain minimum 20-30 mm between wells; pipette carefully; ensure plates are poured on a level surface. |

| No zone with active sample | Well bottom not sealed, leading to sample leakage underneath the agar. | Ensure the well borer is sharp and agar is properly set. Gently press the well after creation if necessary. |

| Zone in negative control well | The solvent used has intrinsic antimicrobial activity at the tested concentration. | Use an alternative, non-inhibitory solvent or further dilute the solvent in the final sample [12]. |

| Inconsistent zone sizes between replicates | Non-uniform well diameters; inaccurate pipetting of sample volumes. | Use a high-quality, consistent well borer; calibrate and use precision micropipettes. |

| Weak or no activity with known antimicrobial | Incompatibility of the sample with the agar medium (e.g., lipophilic compounds). | Consider using a different method, such as broth dilution, or adding surfactants to aid diffusion, though this requires validation [12]. |

Within the framework of a comprehensive thesis on antimicrobial activity screening, the agar well diffusion method serves as a fundamental, qualitative technique for the preliminary evaluation of test compounds against target microorganisms [6]. The incubation step is a critical phase where controlled environmental conditions facilitate the interaction between the diffused antimicrobial agent and the inoculated microbial lawn. Standardizing incubation parameters is paramount to ensuring the reproducibility and reliability of the resultant zones of inhibition (ZOI), which form the basis for initial activity assessments [2]. This protocol details the optimal incubation conditions and timing to achieve consistent and interpretable results.

Standardized Incubation Parameters

The table below summarizes the core incubation parameters for bacterial assays, as established by standardized guidelines such as those from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [2].

Table 1: Standard Incubation Conditions for Bacterial Assays via Agar Well Diffusion

| Parameter | Typical Standardized Condition | Notes & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 35 ± 2 °C | The standard for most human bacterial pathogens; some environmental isolates may require different temperatures [2]. |

| Atmosphere | Ambient Air | Standard for non-fastidious, aerobic bacteria. Fastidious organisms (e.g., some streptococci) may require CO₂-enriched atmospheres [2]. |

| Duration | 16–24 hours | The standard timeframe for visible ZOI formation in most common bacteria. Incubation beyond 24 hours is not recommended as it can allow the agent to degrade or the test microorganism to grow into the inhibition zone [20] [2]. |

| Plate Orientation | Inverted (Lid Down) | Prevents condensation from accumulating on the agar surface, which could disrupt the diffusion of the antimicrobial agent and blur the zone edges [20]. |

Experimental Protocol for Incubation and Post-Incubation Analysis

Materials Needed:

- Inoculated agar plates with test and control wells prepared as per previous protocol steps [20].

- Temperature-calibrated incubator.

- Refrigerator (2–8 °C).

- Vernier calipers or a precise ruler.

- Data recording sheet.

Procedure:

- Pre-incubation Diffusion:

- After placing the test solutions into the wells, leave the plates on a level, sterile surface at room temperature for approximately 1 hour [6]. This pre-incubation diffusion period allows the antimicrobial agent to begin diffusing into the agar before microbial growth initiates, helping to establish a more defined concentration gradient.

Incubation:

- Transfer the plates to the incubator, ensuring they are placed in an inverted position (lid down).

- Set the incubator to the predetermined temperature (e.g., 35 ± 2 °C).

- Incubate the plates for the designated period, typically 16–24 hours. Do not stack plates densely to ensure uniform heat and air circulation.

Post-Incubation Handling:

- After the incubation period, remove the plates from the incubator.

- If measurement cannot be performed immediately, plates can be refrigerated (~4 °C) for a few hours to halt further microbial growth. However, measurements should be taken as soon as possible [2].

Measurement of Zones of Inhibition (ZOI):

- Examine each plate for the presence of clear, circular zones around the wells where bacterial growth has been inhibited.

- Using vernier calipers or a ruler, measure the diameter of each inhibition zone in millimeters (mm), including the well's diameter [20].

- Measure the zones from the underside of the Petri dish without opening the lid.

- For clear, circular zones, take a single diameter measurement. For faint or irregularly shaped zones, measure the clearest edge and note the irregularity.

Interpretation and Documentation:

- Record all measurements systematically.

- Larger inhibition zones generally indicate greater antibacterial activity [20].

- Compare the zones of the test substances to those of the positive (known antibiotic) and negative (solvent alone) controls to validate the assay.

- Note that the well diffusion method is primarily qualitative; it indicates the presence of antimicrobial activity but does not directly provide Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values [6].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete incubation and analysis process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Agar Well Diffusion Assays

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) | The recommended medium for routine antibacterial susceptibility testing. It is well-defined and demonstrates good batch-to-batch reproducibility, allowing for consistent diffusion of most antimicrobial agents [2]. |

| Nutrient Agar | A general-purpose medium often used for antimicrobial screening of non-fastidious microorganisms and for maintaining stock cultures [20] [6]. |

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CAMHB) | Used for preparing the standardized bacterial inoculum to ensure correct ion concentration, which can affect the activity of certain antibiotics [21]. |

| 0.85% Saline Solution | A sterile isotonic solution used for diluting bacterial cultures to achieve the standard inoculum density, typically equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard [21]. |

| Positive Control Antibiotic | A known antibiotic (e.g., ampicillin, chloramphenicol) used to validate the test procedure and provide a benchmark for the performance of the test substance [20] [6]. |

| Sterile Cork Borer / Pipette Tip | For creating uniform wells (typically 5–8 mm in diameter) in the agar medium to receive the test solution [20] [6]. |

| Vernier Calipers | Essential for obtaining precise and accurate measurements of the zones of inhibition in millimeters, ensuring quantitative data from a qualitative method [20]. |

Within the framework of research employing the agar well diffusion method for antimicrobial activity screening, the measurement of zones of inhibition (ZOI) and the subsequent data interpretation constitute a critical, definitive step. This phase transforms the visual results of the bioassay into quantitative and qualitative data, enabling researchers to assess the efficacy of a test compound [22]. The agar well diffusion method is a widely used, cost-effective technique for evaluating the antimicrobial potential of natural extracts, synthetic compounds, and other novel agents [1] [23].

This protocol outlines a standardized procedure for accurately measuring ZOIs, interpreting the data within the appropriate experimental context, and implementing necessary quality controls to ensure result reliability. Adherence to this detailed guide is paramount for generating reproducible and scientifically valid data that can be compared across different studies and for guiding further investigation into promising antimicrobial candidates [24].

Principle of Measurement

The core principle of the agar well diffusion assay is that an antimicrobial agent diffuses from a well into the surrounding agar medium, which has been seeded with a test microorganism. This creates a concentration gradient of the agent. Where the concentration is sufficient to inhibit microbial growth, a clear area termed the zone of inhibition (ZOI) forms around the well [6] [23]. The diameter of this zone is a function of several factors, including the sensitivity of the microorganism, the diffusibility of the antimicrobial agent, and the initial concentration of the agent in the well.

Materials and Equipment

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Incubated Agar Plates | Plates containing the test organism, incubated for the specified time and temperature, showing visible zones of inhibition. |

| Digital Calipers | Provides highly accurate and precise measurements of zone diameters, preferred over standard rulers for research purposes. |

| Vernier Calipers | An alternative mechanical tool for precise measurement. |

| Ruler with Millimeter Graduations | A acceptable, though less precise, tool for measurement if calipers are unavailable. |

| High-Resolution Scanner or Camera | For creating a permanent, digital record of the plate for documentation, re-measurement, or analysis software. |

| Antibiotic Standards (Positive Controls) | Reference antimicrobials (e.g., ampicillin, chloramphenicol) used to validate the assay and for comparative interpretation [6]. |

| Solvent Controls (Negative Controls) | The solvent used to dissolve the test compound (e.g., DMSO, methanol) to confirm it does not itself produce a zone of inhibition. |

Step-by-Step Measurement Protocol

Pre-Measurement Preparation

- Remove Plates from Incubator: After the standardized incubation period (typically 16-24 hours for most fast-growing bacteria), remove the agar plates from the incubator.

- Visual Inspection: Examine each plate for well-defined, circular zones of inhibition. The zone is identified by a clear area where bacterial growth has been inhibited, surrounding the central well.

- Documentation: Capture a high-resolution digital image of the entire plate against a dark, non-reflective background. Ensure the image includes a scale (e.g., a ruler placed next to the plate). This serves as a permanent record and allows for verification.

Measurement Procedure

- Tool Selection: Use a pair of digital calipers for maximum accuracy. Ensure the calipers are zeroed before use.

- Hold the Plate: Place the plate on a flat, well-lit surface. For safety, ensure the plate lid remains on if possible, or work quickly in a biosafety cabinet to prevent contamination.

- Measure the Diameter:

- Position the caliper's tips across the center of the well, measuring the diameter of the clear zone from one end to the other.

- Measure in Millimeters: Take the measurement from the outer edge of the well to the opposite outer edge of the clear zone. Do not include the diameter of the well itself in the final recorded value, unless specified by an alternative methodology.

- Repeat: Perform the measurement at least twice for each zone, rotating the plate approximately 90 degrees between measurements to account for any minor irregularities. If the zone is not perfectly circular, take multiple measurements and calculate the average diameter.

Data Recording

- Record the raw measurement(s) for each well immediately in a laboratory notebook or electronic data capture system.

- Clearly label each measurement with the corresponding plate identifier, well number, test compound, and concentration.

- Note any anomalies, such as irregular zone shapes, double zones, or faint inhibition, as these may indicate specific interactions or technical issues.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete process from plate preparation to final data interpretation.

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Qualitative and Quantitative Interpretation

The measured zone diameter provides a semi-quantitative assessment of antimicrobial activity. The following table offers a general guideline for interpreting results, though organism-specific and compound-specific breakpoints should be established.

| Zone of Inhibition Diameter (mm) | Interpretation | Implication for Test Compound |

|---|---|---|

| No observable zone | No activity | The compound is ineffective at the tested concentration under these conditions. |

| < 8 mm | Weak activity | May warrant further testing at higher concentrations or with different methods. |

| 8 - 14 mm | Moderate activity | Suggests the compound has promising antimicrobial potential. |

| 15 - 19 mm | Strong activity | Indicates a highly effective antimicrobial agent. |

| ≥ 20 mm | Very strong activity | A very potent compound, comparable to strong standard antibiotics. |

Comparative Analysis with Controls

- Positive Control: The zone size of the standard antibiotic validates the test system's functionality. The activity of the test compound can be qualitatively compared to this standard [6].

- Negative Control: The solvent should produce no zone of inhibition. A zone here indicates the solvent is toxic or antimicrobial, invalidating the results for that solvent.

Key Considerations for Accurate Interpretation

- Diffusibility: Compounds with high molecular weight or poor water solubility may diffuse poorly, leading to smaller zones that do not accurately reflect their intrinsic antimicrobial potency [23].

- Agar Depth and Composition: Thicker agar layers or different media can restrict diffusion and reduce zone sizes. Consistency across plates is critical [24].

- Inoculum Density: A heavier inoculum density can lead to smaller or less distinct zones of inhibition. The inoculum must be standardized to a specific turbidity (e.g., 0.5 McFarland standard, ~1 x 10^8 CFU/mL) [6] [23].

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Accurate data interpretation requires awareness of potential anomalies and implementation of robust quality control measures. The following diagram outlines a systematic approach to addressing common issues.

Quality Control Measures

- Replication: All tests should be performed in at least triplicate to ensure reproducibility and allow for statistical analysis.

- Standardized Reference Strains: Use quality-controlled strains from culture collections (e.g., ATCC) such as Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) for assay validation [23].

- Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs): Develop and adhere to detailed SOPs for every stage, from inoculum preparation to incubation, to minimize inter-assay variability.

The agar well diffusion method is a cornerstone technique in antimicrobial activity screening, providing a accessible and effective means to evaluate the efficacy of various test substances [1]. This method is particularly valuable for initial screenings of complex biological samples, such as cell-free supernatants (CFS) and plant extracts, where the active antimicrobial components may not be fully characterized [25] [8]. Its principle relies on the diffusion of test compounds from a reservoir (a well) into a solid growth medium seeded with a test microorganism. If the compounds possess antimicrobial properties, they create a clear zone of inhibition around the well, the diameter of which corresponds to the substance's efficacy [1] [9].

This protocol details the application of the agar well diffusion method for screening two key classes of substances: CFS from lactic acid bacteria (LAB) fermentations and antimicrobial plant extracts. The method's utility in this context is demonstrated by its application in recent, cutting-edge research, making it an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals working to discover novel antimicrobial agents [25] [26].

Key Applications and Supporting Data

The agar well diffusion assay is extensively used for the primary screening of antimicrobial activity from diverse sources. The table below summarizes quantitative findings from recent studies investigating cell-free supernatants and plant-derived products.

Table 1: Quantitative Findings from Agar Well Diffusion Assays on Various Substances

| Test Substance | Source / Type | Test Microorganism | Inhibition Zone Diameter (mm) | Key Finding / Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAB Cell-Free Supernatant | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum K014 (in MRS broth) | Cutibacterium acnes | 23.67 | Highest activity among 10 screened LAB strains [25]. |

| LAB CFS (Plant-Based Medium) | L. plantarum K014 (in Brown Rice medium) | Cutibacterium acnes | 16.00 | Demonstrated efficacy of plant-based fermentation [25]. |

| Optimized LAB CFS | L. plantarum K014 (Optimized Brown Rice medium) | Cutibacterium acnes | 21.67 | Response surface methodology enhanced activity [25]. |

| Danish Honey | Water Mint (Mentha aquatica) | Staphylococcus aureus | Varying | Exhibited greater effect than medical-grade Manuka honey [26]. |

| Antimicrobial Nanoparticles | Bimetallic AgCu | Multiple bacteria & fungi | Varying (MIC: 7-62.5 µg/mL) | Agar well diffusion identified as the most reliable primary method [9]. |

Experimental Protocols

Agar Well Diffusion Assay for Cell-Free Supernatants

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study screening LAB supernatants against C. acnes [25].

Materials Required:

- Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) or Nutrient Agar (NA) plates [25] [9].

- Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth for cultivating C. acnes [25].

- Sterile cotton swabs.

- Sterile cork borer or tip (6-8 mm diameter).

- Micropipette and sterile tips.

Procedure:

- Preparation of Test Organism: Inoculate C. acnes into BHI broth and incubate at 37°C until a turbid suspension is achieved. Adjust the suspension to a density of approximately 1.5 × 10^8 CFU/mL (equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard) [25].

- Inoculation of Agar Plates: Using a sterile cotton swab, dip into the adjusted microbial suspension and swab it evenly over the entire surface of the MHA or NA plate to create a uniform bacterial lawn. Allow the surface to dry for a few minutes [25].

- Creation of Wells: Using a sterile cork borer or pipette tip, punch 6-mm diameter wells into the solidified agar [25].

- Loading the Test Substance: Pipette 100 µL of the cell-free supernatant (centrifuged and pH-neutralized if necessary) into the well. Ensure not to overfill. A negative control (e.g., sterile growth medium) should be included [25].

- Incubation: Seal the plates and incubate them at 37°C for 48 hours under anaerobic conditions suitable for C. acnes [25].

- Measurement: After incubation, measure the diameter of the clear zone of inhibition around the well in millimeters (mm) using a caliper or ruler [25].

Agar Well Diffusion Assay for Plant Extracts

The following workflow outlines the key steps in preparing and testing plant extracts using the agar well diffusion method, incorporating best practices for handling hydrophobic compounds [27] [28].

Procedure Details:

- Plant Extract Preparation: The first step involves the maceration of plant material, typically using a solvent like methanol for immersion to extract bioactive compounds [28].

- Sample Preparation: For essential oils or non-water-soluble extracts, dissolve the sample in a suitable water-miscible solvent like DMSO or Tween 80. The final concentration of the solvent in the well should not possess antimicrobial activity itself (generally ≤1%) [27].

- Lawn Preparation and Well Creation: Follow the steps outlined in section 3.1 (steps 2 and 3) to prepare the bacterial lawn and create wells. Common test organisms include Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli [26].

- Loading Samples: Pipette 50-100 µL of the prepared plant extract into the well [26] [28].

- Incubation and Measurement: Incubate the plates at 37°C for 18-24 hours (or as required by the test microorganism), then measure the zones of inhibition [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of the agar well diffusion assay requires specific materials and reagents. The following table lists key solutions and their critical functions in the protocol.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Agar Well Diffusion

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Assay | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | Supports growth of the test microorganism. | Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA): The standard non-selective medium for antimicrobial susceptibility testing [9]. Brain Heart Infusion (BHI): Used for fastidious organisms like C. acnes [25]. |

| Emulsifiers / Solvents | Dissolves and disperses hydrophobic samples for effective diffusion. | DMSO, Tween 80, Polysorbate 80: Critical for testing essential oils and plant extracts. Must be non-inhibitory at working concentrations [27]. |

| Standardized Inoculum | Ensures consistent and reproducible microbial growth. | 0.5 McFarland Standard (~1.5 x 10^8 CFU/mL): Used to standardize the density of the bacterial suspension for lawn preparation [25]. |

| Positive Control | Validates the setup and sensitivity of the test organism. | Known antibiotics (e.g., Chloramphenicol) or reference antimicrobials (e.g., medical-grade Manuka honey) [26]. |

| Negative Control | Confirms that observed activity is from the test substance. | Sterile growth medium (for CFS) or solvent/emulsifier alone (for extracts) [25] [27]. |

Critical Considerations for Robust Results

To ensure reliable and interpretable results, researchers must account for several key variables:

- Sample Physicochemical Properties: The hydrophobicity, molecular size, and volatility of antimicrobial compounds in plant extracts or CFS significantly impact their diffusion rate through the agar matrix. This can lead to variations in zone sizes that do not always directly correlate with overall potency [27].

- Method Customization: The assay can be adapted for different sample types. For instance, when working with CFS, steps like pH neutralization or heat treatment can help distinguish the effects of organic acids from other antimicrobial metabolites like bacteriocins [25] [26].

- Reproducibility and Validation: While the agar well diffusion is an excellent primary screen, it is primarily a qualitative to semi-quantitative method. For a more precise quantitative assessment, follow-up tests such as broth dilution methods to determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) are recommended [9].

Solving Common Problems and Enhancing Assay Performance

Addressing Challenges with Lipophilic Compounds and Solvent Effects

The agar well diffusion method is a cornerstone technique for initial antimicrobial activity screening due to its low cost, simplicity, and ability to handle multiple samples simultaneously [23]. However, its application in evaluating natural products and novel chemical entities is significantly hampered when dealing with lipophilic compounds. The inherent aqueous nature of standard agar matrices creates a fundamental incompatibility with hydrophobic substances, leading to poor diffusion and potential false-negative results [23]. This challenge is frequently encountered in ethnopharmacology research, such as studies on Annona senegalensis root bark, where bioactive lipophilic fractions and kaurenoic acid demonstrate potent antibacterial effects but require specialized extraction and fractionation using methanol-methylene chloride and ethyl acetate [29]. Similarly, research on lipophilic fractions from thermophilic cyanobacteria (Leptolyngbya sp.) against vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) underscores the therapeutic importance of these compounds and the critical need for robust methods to evaluate their activity [30]. This application note details the specific challenges and provides optimized, actionable protocols to enhance the reliability of agar well diffusion assays for lipophilic antimicrobial agents, framed within a thesis on methodological advancements in antimicrobial screening.

Key Challenges and Quantitative Data

Lipophilic compounds face several specific barriers in standard agar diffusion assays. The primary issue is limited diffusion through the aqueous agar matrix, which restricts the compound's ability to form a concentration gradient and a discernible zone of inhibition [23]. Furthermore, the choice of solvent is critical; it must adequately dissolve the compound without itself inhibiting bacterial growth or physically distorting the agar. The following table summarizes the core challenges and their implications for the assay.

Table 1: Core Challenges of Lipophilic Compounds in Agar Well Diffusion